达尔文

| 姓名 | 查尔斯·罗伯特·达尔文 Charles Robert Darwin |

| 出生 | 1809年2月12日,什鲁斯伯里的达尔文庄园,英格兰什罗普郡 |

| 逝世 | 1882年4月19日(73岁),Down House,郡达温,肯特,英格兰 |

| 公墓所在地 | 威斯敏斯特大教堂 |

| 闻名于 | 猎犬号航行;物种起源;人类的由来 |

| 配偶 | Emma Wedgwood (结婚于. 1839年) |

| 儿女 | 10 |

| 获奖 | |

| 领域 | 自然历史,地质 |

| 机构 |

|

| 学术顾问 | John Stevens Henslow |

| 影响 | Charles Lyell;Alexander von Humboldt;John Herschel;Thomas Malthus;Gilbert White |

| 影响于 | Hooker, Huxley, Romanes, Haeckel, Lubbock |

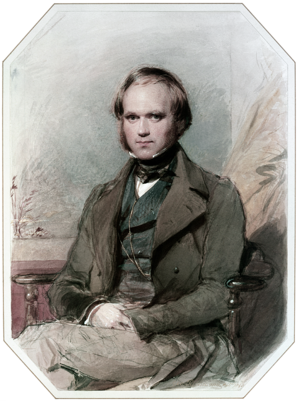

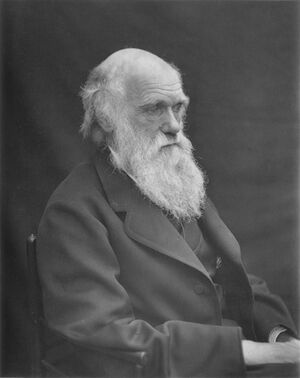

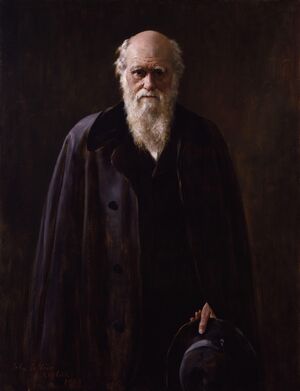

查尔斯·罗伯特·达尔文 Charles Robert Darwin[1](1809年2月12日-1882年4月19日)是英国博物学家,地质学家和生物学家[4]。他因对进化科学的贡献而闻名。他认为,所有的生命物种都拥有着共同祖先,只是随着时间的流失不停地进化而来。现在该假设已被广泛接受,同时被认为是科学的理论基础[5]。在与Alfred Russel Wallace的联合出版物中,他详细介绍了他的科学理论,即这种进化的分支模式是由被他称为自然选择 Natural selection的过程产生的。在这个过程中,生物为生存而进行的斗争与参与选择性育种 Selective breeding[6]的人工选择具有相似的作用。达尔文当选为人类历史上最有影响力的人物之一[7]。为了纪念他,人们为他在威斯敏斯特教堂[8]举行了葬礼,这是至高的荣誉。

达尔文在1859年出版的《物种起源 On the Origin of Species 》[9][10]一书中,以令人信服的证据发表了他的进化论。到了19世纪70年代,科学界和大多数受过教育的公众已经开始接受进化论这一事实。但是,仍然有许多人持有不同的解释,认为自然选择的作用很小,直到二十世纪三十到五十年代,才开始出现 现代进化综合论Modern evolutionary synthesis ,之后逐渐形成了广泛共识,并且认为自然选择是进化的基本机制[11][12]。达尔文的科学发现是生命科学的综合理论,解释了生命的多样性[13][14]。

一开始达尔文对自然的兴趣使他轻视了在爱丁堡大学的医学教育。相反,他帮助调查了海洋无脊椎动物。在剑桥大学基督学院的研究工作激发了他对自然科学[15]的热情。他在比格犬号HMS Beagle经历的为期五年的航行使他成为了一位杰出的地质学家,他的观察和理论为查尔斯·莱尔Charles Lyell提出的地质变化渐进概念提供了支持,后期他出版的航行日记使他同时成为了著名的作家[16]。

在长达五年的航行过程中,达尔文对收集到的野生动植物和化石的地理分布记录感到困惑,于是开始了详细的研究,并于1838年提出了他的自然选择理论[17]。尽管他与数位博物学家讨论了他的想法,但他仍需要时间进行更广泛的研究来验证,而且他的本职地质工作仍然需要继续[18]。1858年,当阿尔弗雷德·罗素·华莱士 Alfred Russel Wallace给他写了一篇描述同样想法的文章时,他正在撰写自己的理论,因此就促使了他们联合发表他们的理论[19]。达尔文的工作建立了适应性调节进化的理论基础,作为自然界多元化[11]的主要科学解释。1871年,他在《人类起源和性选择 The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex》一书中研究了人类的进化和性选择,以及与性相关的其他选择,之后在1872年还出版了另一本书《人与动物的情感表达 The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals》。他对植物的研究也发表在一系列著作中,在他的最后一本书《通过蠕虫的作用而形成的植物霉菌 The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms》(1881年)中,他研究了蚯蚓及其对土壤[20][21]的影响。

个人简介

早年生活和教育经历

查尔斯·罗伯特·达尔文于1809年2月12日出生在什罗普郡的什鲁斯伯[22][23]里山顶的小屋里,在六个孩子中排行第五。他的父亲是非常富裕的社会医生和金融家罗伯特·达尔文 Robert Darwin,母亲苏珊娜·达尔文nSusannah Darwin则是韦奇伍德陶器家族的女儿。他的祖父伊拉斯谟·达尔文 Erasmus Darwin和约西亚·韦奇伍德 Josiah Wedgwood都是著名的废奴主义者。伊拉斯谟·达尔文在他的著作《动物法则 Zoonomia》(1794年)中称赞了进化和共同祖先这个概念。本书以一种渐进式创作的诗意幻想方式呈现,其中也含有一些尚未成熟的观念,这些观点也成为他孙子未来所提出的理念的雏形[24]。

尽管韦奇伍德一家信仰英国国教,但两个家庭基本上都是一神论主义者。罗伯特·达尔文本身是一名沉默且坚定地信奉自由主义者的人。他于1809年11月在什鲁斯伯里英国国教圣乍得教堂为达尔文进行了洗礼,但他和他的兄弟姐妹,还有母亲则一起去一神论教堂祷告。八岁的达尔文在1817年加入由传教士经营的日间学校时,已经对自然历史和收藏产生了兴趣。同年七月,他的母亲不幸去世了。从1818年9月起,他与哥哥伊拉斯谟一起在附近的圣公会什鲁斯伯里学校作为寄宿生就读。[25]

1825年夏天,达尔文作为实习医生,帮助父亲治疗什罗普郡的穷人,然后在1825年10月与他的兄弟伊拉斯谟一起就读于爱丁堡大学医学院(当时是英国最好的医学院)。达尔文渐渐发现医学讲座乏味,手术令人痛苦,因此他对学业丧失了兴趣。后来,他在约翰·埃德蒙斯顿John Edmonstone那里坚持了40天,每天大约一小时长的课程,学到动物标本剥制术。约翰·埃德蒙斯顿是一名重获自由的黑人奴隶,曾陪伴查尔斯·沃特顿Charles Waterton进入过南美雨林[26]。

达尔文在大学的第二年,加入了布里尼学会Plinian Society,这是一个由一群研究自然历史的学生组成的团体,其中经常会有激烈的辩论关于民主学生以唯物主义的观点挑战正统的科学宗教观念。在这期间,达尔文协助罗伯特·埃德蒙·格兰特Robert Edmond Grant对福斯峡湾Firth of Forth海洋无脊椎动物的解剖结构和生命周期进行了调查,并于1827年3月27日在布里尼学会期刊上提出了自己的发现,即牡蛎壳中发现的黑孢子是滑冰水蛭的卵。有一天,格兰特称赞拉马克的进化思想。格兰特的大胆令达尔文感到十分震惊,但当时他在祖父伊拉斯谟日记[27]中也读到了类似的观点。

同时期,达尔文还选择了罗伯特·詹姆森Robert Jameson教授的自然历史课程,涵盖了地质学,包括 水成论Neptunism与 火成论Plutonism之间的争辩,但这使达尔文倍感无聊。他转向开始了解植物的分类,并协助大学博物馆开展收藏工作,当时该大学拥有欧洲最大的博物馆之一。[28]

达尔文对医学研究的忽视使他的父亲大为恼火,于是他特地将达尔文送到了剑桥大学基督学院去攻读文学学士学位,因为这是迈向成为英国国教乡村牧师的第一步。但由于达尔文不符合文学士荣誉学位考试资格标准,于是他在1828年1月选择了普通学位课程[29]。然而相较于学习,他更喜欢骑马和射击。在达尔文入学的头几个月,他的第二任堂兄威廉·达尔文·福克斯William Darwin Fox也进入基督教堂读书。福克斯的蝴蝶收藏给他留下了深刻的印象,并让达尔文了解了昆虫学,促使他开始了甲虫收藏[30][31]。渐渐地,他对此产生了极大的兴趣,并在詹姆斯·弗朗西斯·史蒂芬斯 James Francis Stephens的《 英国昆虫图志Illustrations of British entomology 》[31][32](1892-32年)中提出了一系列发现。也是通过福克斯的引荐,达尔文成为了植物学教授约翰·史蒂文斯·汉斯洛[30]的密友和追随者。随后他遇到了其他一流的牧师自然学家,他们将科学工作视为宗教自然神学,并被这些教员称为“与汉斯洛同行的人”。当他自己的考试临近时,达尔文开始专心学习。他对威廉·佩利William Paley的《 天道溯源Evidences of Christianity 》[33](1794)中描述的语言和逻辑感到惊喜。后来达尔文在1831年1月的期末考试中表现出色,在178个普通学位候选人中排名第十。[34]

为了能够顺利毕业,达尔文必须在剑桥待到1831年6月。期间他研究了佩利Paley的《 自然神学Natural Theology 》和《 神存在与其属性的证据Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity 》(于1802年首次出版),该书为自然界中的神性设计辩解,解释了生物的适应性行为其实是神通过自然法则行事[35]。他阅读了约翰·赫歇尔John Herschel的新书《 自然哲学研究的初步论述Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy 》(1831),其中描述了自然哲学的最高目标,即通过基于观察的归纳推理来理解此类定律,以及亚历山大·冯·洪堡Alexander von Humboldt于1799–1804年科学旅行的个人叙事记录。[36][37]

猎犬号的航行调查

在离开威尔士的塞奇威克后,达尔文在巴茅斯与学生朋友待了一个星期,于8月29日返回家乡,并收到了汉斯洛的来信。信中汉斯洛建议他考虑一下做个博物学家,并与船长罗伯·菲茨罗伊Robert FitzRoy一起为HMS Beagle猎犬号自筹资金,这样或许可以得到一个编外名额从而登船。汉斯洛特地强调这是一个绅士的职位,而不是“单纯的收集者”。该船将在四周内离开,以绘制南美海岸线图[38]。该船将于四周内启航,绘制南美海岸线图。罗伯特·达尔文反对儿子未来的两年航程,他认为这是在浪费时间,但他的姐夫约西亚·韦奇伍德二世Josiah Wedgwood II说服了他同意并资助儿子的计划[39]。后来达尔文小心翼翼地以私人身份保留着对藏品的控制权,他打算将其投入于大型科学机构。[40]

航行后来延误到1831年12月27日启航,而且它持续了将近五年。正如菲茨罗伊所希望的那样,达尔文大部分时间都在土地上进行地质调查和自然历史采集[11][41] ,而HMS Beagle则在调查和绘制海岸图。他仔细记录了自己的观察和理论推测,并在航行中不定期将标本与信件一起寄到剑桥,其中包括他的家人日记[42]。他在地质学、甲虫收集和解剖海洋无脊椎动物方面具有一定的专业知识,但在其它所有领域都是新手。不过他会妥善收集标本并供专家评估。[43]尽管遭受晕船之苦,达尔文还是在船上写下了大量笔记。他的大部分动物学笔记都是关于海洋无脊椎动物的,自无风期的浮游生物开始。[41][44]

达尔文在佛得角圣哈戈上岸的第一站中,发现火山岩峭壁中高处白色带中包含贝壳。菲茨罗伊为他提供了查尔斯·莱尔Charles Lyell的《 地质学原理Principles of Geology 》的第一卷,其中阐述了土地在各个时期缓慢上升或下降的统一概念。达尔文看到了莱尔所作的一切,他也在思索着写地质学[45]著作的想法。当他们到达巴西时,达尔文对热带森林[46]感到惊喜好奇,但也因目睹奴隶制的景象而感到愤怒,并与菲茨罗伊产生了争执[47]。

后来调查继续在巴塔哥尼亚南部进行。他们在巴伊亚布兰卡停了下来,在蓬塔阿尔塔附近的悬崖上的一堆现代贝壳的旁边,达尔文发现了大量已灭绝哺乳动物的化石,这表明最近的灭绝并不是因为气候或灾难的变化。他用牙齿识别出了鲜为人知的大地懒,并将其与骨甲联系起来,在他看来,它最初看起来像是本地犰狳身上的巨型盔甲。这些发现到达英国后引起了当地研究学者极大的兴趣。[48][49]

在高乔人随同下,达尔文进入领地内去探索地质并收集更多化石,他因此对本土人民和革命时期殖民地人民的社会,政治和人类学方面都获得了独到的见解。并了解到两种类型的美洲鸵具有独立但重叠的领地。在更南的地方,他还看到阶梯状的带状平原和贝壳状的高架海滩,它们呈现出一系列不同的高地[50][51] 。他阅读了莱尔的第二卷,接受了其关于物种“创造中心”的观点,但是他的发现和理论挑战了莱尔关于平稳连续性和物种灭绝的思想。[52][53]

在第一次的猎犬号航行中,船上的3名火地岛人被抓获,然后他们在英国接受了一年的传教士教育。达尔文发现他们友好且文明,但在火地岛,他也遇到了区别如家养动物和野生动物不同的“悲惨的,退化的野蛮人”[54]。他仍然坚信,尽管存在这种多样性,但所有人类都具有共同的血统和改善文明的潜力。与科学家朋友不同,他现在认为人与动物之间没有不可逾越的鸿沟[55]。一年后,该教育任务停止了,其中一位他们曾取名为杰米·巴顿Jemmy Button的火地岛人过着与其他当地人一样的生活,娶了一位妻子,而且他不愿再返回英国。[56]

达尔文于1835年在智利经历了一次地震,并看到土地刚刚被抬高的迹象,包括在涨潮时搁浅的蚌床。在安第斯山脉的高处,他还看到了贝壳,以及在沙滩上生长的几棵化石树。他因此得到的理论是,随着土地的上升,海洋岛屿沉没,周围的珊瑚礁逐渐形成环礁。[57][58]

在地理意义上新发现的加拉帕戈斯群岛上,达尔文寻找证据证明野生生物具有“创造中心”这一观点,他发现了智利存在一种类似的,但在各个岛屿之间又有所不同的知更鸟。他听说根据乌龟壳略有变化的形状,可以得知它们来自哪个岛,但最后他即使食用了船上的乌龟,也未能将它们收集起来。[59][60]在澳大利亚,存活着鼠袋鼠和鸭嘴兽似乎很不寻常,以至于达尔文依稀觉得好像两个不同的造物者在工作[61]。他发现原住民“幽默愉快”,并注意到本岛上那些欧洲定居点对原住民的文化个性的影响,促使其消失。[62]

菲茨罗伊研究了科科斯基林群岛环礁的形成方式,并为达尔文的理论提供了支持[58]。随后他开始撰写猎犬号航行的官方叙事,在阅读达尔文的日记后,他提议将其纳入其中[63]。最终,《达尔文日记Darwin's Journal》被改写为单独的第三卷,归类为自然史。[64]

在南非的开普敦,达尔文和菲茨罗伊会见了约翰·赫歇尔John Herschel,约翰曾写过信给莱尔,称赞他的均变论是非常大胆的猜测,将“近乎玄学的概念,由其他未知物种替代已灭绝的物种”,看作是“与奇迹般的过程形成鲜明对比的自然现象”。[65]

达尔文在返航时整理了他的笔记,他写道,他对知更鸟,乌龟和福克兰群岛的狐狸的物种相似性和区别不断产生怀疑,因为“这些事实破坏了物种的稳定性”,所以他在“破坏”前面谨慎地加上了“可能将会”[66]。他后来写道,这些事实“似乎让我对物种起源有了一些了解”。[67]

达尔文进化论的诞生

当达尔文回到英国的时候,他已经是科学界的名人了。因为1835年12月,汉斯洛专为某些博物学家们出版了达尔文的地质学书信册,从而提高了他以前的学生声誉[68]。1836年10月2日,这艘船停泊在康沃尔郡的法尔茅斯。达尔文立马开始了漫长的教练旅程,他回到什鲁斯伯里的家并探望亲戚。随后,他急忙去剑桥看汉斯洛,汉斯洛建议他去找那些能够分类他收集的动物名单,并同意采集植物标本的博物学家。达尔文的父亲负责投资,使他的儿子成为一名自费的绅士科学家,而兴奋的达尔文则前往伦敦一家机构,寻找专家来描述他的那些藏品。当时英国的动物学家们积压了大量工作,因为大英帝国促进和鼓励动物学们进行自然历史的收集,而且将标本留在仓库中也确实危险。

查尔斯·莱尔于10月29日首次与达尔文会面,并很快将他介绍给了崭露头角的解剖学家理查德·欧文Richard Owen,欧文可以使用皇家外科医学院的设施,因此他可以处理达尔文收集的化石。欧文也在随后发现了令人惊讶的成果,包括已灭绝的巨大地面树懒以及大地懒,一个近乎完整的伏地懒全骨,和一只河马大小的啮齿动物般的头骨,名为Toxodon,类似于巨大的水豚。还有一些来自雕齿兽盔甲的碎片--达尔文最初以为它是巨大犰狳类动物[69][49]。所有这些灭绝的生物发现与南美的生物物种有关。[70]

同年12月中旬,达尔文寄宿在剑桥,整理他航行中收集的动植物化石标本并重新开始写他的期刊论文[71]。他写的第一篇论文表明了南美大陆正在缓慢上升。他得到了莱尔的热情支持,于1837年1月4日将其发给了伦敦地质学会。当天,他向动物学协会展示了他的哺乳动物和鸟类标本。鸟类学家约翰·古尔德John Gould很快宣布,达尔文认为的加拉帕戈斯鸟类是黑鸟 -- “喙喙”和十二种雀科的杂交种。2月17日,达尔文被选入理事会地质学会,莱尔的总统发言介绍了欧文关于达尔文化石的发现,并强调了物种的地理连续性可以支撑他的均变论观点。[72]

Early in March, Darwin moved to London to be near this work, joining Lyell's social circle of scientists and experts such as Charles Babbage,[73] who described God as a programmer of laws. Darwin stayed with his freethinking brother Erasmus, part of this Whig circle and a close friend of the writer Harriet Martineau, who promoted Malthusianism underlying the controversial Whig Poor Law reforms to stop welfare from causing overpopulation and more poverty. As a Unitarian, she welcomed the radical implications of transmutation of species, promoted by Grant and younger surgeons influenced by Geoffroy. Transmutation was anathema to Anglicans defending social order,[74] but reputable scientists openly discussed the subject and there was wide interest in John Herschel's letter praising Lyell's approach as a way to find a natural cause of the origin of new species.[65]

来年3月初,达尔文搬到伦敦,从事这项工作,加入了莱尔的科学家和专家社交圈,例如查尔斯·巴贝奇Charles Babbage[73],他将上帝描述为法律程序员。达尔文与自由思想的兄弟伊拉斯谟呆在一起,加入了辉格党的圈子,另外,他和作家哈里埃特·马丁诺Harriet Martineau也是密友,哈里埃特推动了马尔萨斯主义Malthusianism的改革,以制止因福利造成人口过剩和更多的贫困,这引起了辉格党穷人法Whig Poor Law的争议。作为一神论者,她赞同 物种演变 Transmutation的深远影响,这个概念由格兰特和受杰夫罗伊影响的年轻外科医生推广。物种演变[74]这个概念,在当时是英国国教为了捍卫社会秩序极力咒逐的,但是著名的科学家们则愿意公开讨论这个话题。约翰·赫歇尔John Herschel在信中赞扬莱尔,他认为这是用自然原因来寻找新物种起源的一种方法,因此引起了学界广泛的兴趣。[65]

Gould met Darwin and told him that the Galápagos mockingbirds from different islands were separate species, not just varieties, and what Darwin had thought was a "wren" was also in the finch group. Darwin had not labelled the finches by island, but from the notes of others on the ship, including FitzRoy, he allocated species to islands.[75] The two rheas were also distinct species, and on 14 March Darwin announced how their distribution changed going southwards.[76]

古尔德Gould后来遇到了达尔文并告诉他,来自不同岛屿的加拉帕戈斯知更鸟是不同的物种,而不仅仅是变种,而且当初达尔文认为的鹪鹩也归属于雀科类。航行中达尔文没有按岛对雀类进行标记,但是从船上其他人(包括菲茨罗伊)的笔记中,他将物种分配到了各个岛上[75]。有两种美洲鸵也是不同的物种,后来3月14日,达尔文宣布其分布向南延伸。[76]

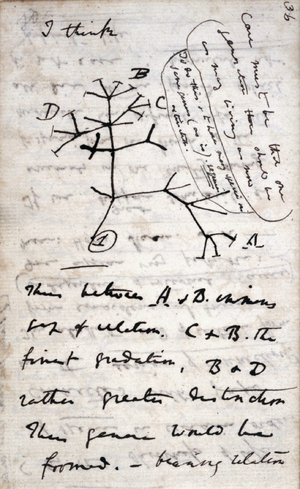

By mid-March 1837, barely six months after his return to England, Darwin was speculating in his Red Notebook on the possibility that "one species does change into another" to explain the geographical distribution of living species such as the rheas, and extinct ones such as the strange extinct mammal Macrauchenia, which resembled a giant guanaco, a llama relative. Around mid-July, he recorded in his "B" notebook his thoughts on lifespan and variation across generations—explaining the variations he had observed in Galápagos tortoises, mockingbirds, and rheas. He sketched branching descent, and then a genealogical branching of a single evolutionary tree, in which "It is absurd to talk of one animal being higher than another", discarding Lamarck's idea of independent lineages progressing to higher forms.[77]

到了1837年3月中旬,即返回英国后仅六个月,达尔文就在他的红色笔记本中推测了这种可能性,他认为“一种物种确实会变成另一种物种”,并用其解释生存的物种(例如,美洲大黄鼠)和灭绝的物种(例如,已灭绝的哺乳动物后弓兽)的地理分布,该物种酷似一种巨大的原驼,是美洲驼的亲戚。大约在7月中旬,他在自己的“B”笔记本中记录了他对寿命和跨代变化的看法,解释他在加拉帕戈斯陆龟,知更鸟和美洲鸵中观察到的变化。他画出了后裔分支,并描绘了单个进化树的家谱分支,其中“谈论一种动物高于另一种动物是荒谬的”,他认为应该摒弃了拉马克Lamarck关于独立血统发展为更高形态的想法。[77]

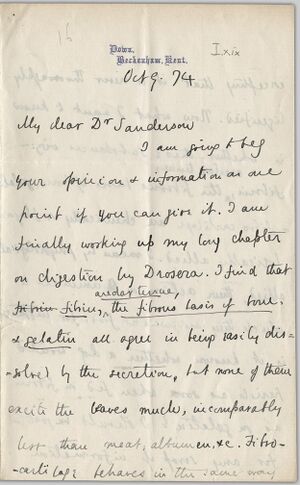

Since 2000, notebooks have been missing from Cambridge University Library that are now believed to have been stolen. One of them contains Darwin's famous Tree of Life sketch (above right), exploring the evolutionary relationship between species. Digitised copies do still exist.[78]

自2000年以来,剑桥大学图书馆一直缺少达尔文的笔记,该笔记已被盗。笔记中包含了达尔文著名的生命之树草图(右上图),探索物种之间的进化关系。不过数字副本仍然存在。[78]

劳累,疾病和婚姻

While developing this intensive study of transmutation, Darwin became mired in more work. Still rewriting his Journal, he took on editing and publishing the expert reports on his collections, and with Henslow's help obtained a Treasury grant of £1,000 to sponsor this multi-volume Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, a sum equivalent to about £模板:Inflation in 2022.模板:Inflation-fn He stretched the funding to include his planned books on geology, and agreed to unrealistic dates with the publisher.[79] As the Victorian era began, Darwin pressed on with writing his Journal, and in August 1837 began correcting printer's proofs.[80]

在深入这项关于演变的研究时,达尔文被工作占据了所有。他仍在重写他的日记并负责编辑和发布其采集化石标本相关的专家报告。同时在汉斯洛的帮助下,他的多卷动物学著作《H.M.S.猎犬号》获得了£1,000的财政部拨款赞助。这本书2018年的总价约为92,000英镑。他节省使用这笔资金,以完成计划中的地质类书刊,并与出版商商定了不切实际的发行日期[79]。后来随着维多利亚时代的开始,达尔文于1837年8月开始更正打印机的样张。[80]

As Darwin worked under pressure, his health suffered. On 20 September he had "an uncomfortable palpitation of the heart", so his doctors urged him to "knock off all work" and live in the country for a few weeks. After visiting Shrewsbury he joined his Wedgwood relatives at Maer Hall, Staffordshire, but found them too eager for tales of his travels to give him much rest. His charming, intelligent, and cultured cousin Emma Wedgwood, nine months older than Darwin, was nursing his invalid aunt. His uncle Josiah pointed out an area of ground where cinders had disappeared under loam and suggested that this might have been the work of earthworms, inspiring "a new & important theory" on their role in soil formation, which Darwin presented at the Geological Society on 1 November 1837.[81]

由于达尔文在强压下工作,他的健康因此受到了影响。9月20日,他的心脏感到“不舒服”,他的医生敦促他“放弃所有工作”,并在该国生活几周。在拜访了什鲁斯伯里之后,他回到了他在斯塔福德郡梅尔大厅的韦奇伍德亲戚家,但发现他们太渴望他的旅行故事,无法给他更多的休息。他有个迷人,聪明,有教养的表姐艾玛·韦奇伍德Emma Wedgwood,比达尔文大九个月,正在照顾他身残的姨妈。他的叔叔约西亚Josiah曾提到过在一块土壤下面消失的煤渣,并暗示这可能是蠕虫的行为,这启发他们思考一个“全新的重要理论” -- 关于蠕虫在土壤行程中的作用,达尔文于1837年11月1日在地质学会上发表相关论文。[81]

William Whewell pushed Darwin to take on the duties of Secretary of the Geological Society. After initially declining the work, he accepted the post in March 1838.[82] Despite the grind of writing and editing the Beagle reports, Darwin made remarkable progress on transmutation, taking every opportunity to question expert naturalists and, unconventionally, people with practical experience in selective breeding such as farmers and pigeon fanciers.[11][83] Over time, his research drew on information from his relatives and children, the family butler, neighbours, colonists and former shipmates.[84] He included mankind in his speculations from the outset, and on seeing an orangutan in the zoo on 28 March 1838 noted its childlike behaviour.[85]

博学通才的著名科学家,哲学家威廉·惠威尔William Whewell敦促达尔文担任地质学会秘书。最初他拒绝了这项工作,但达尔文于1838年3月接受了该职位[82]。尽管在撰写和编辑《H.M.S.猎犬号》时非常不顺利,然而达尔文在演变方面取得了显著进步。他抓住一切机会,向专家,博物学家,以及那些非常规的但是在选育方面有实践经验的人(如农民和鸽友)提问[11][83]。他的研究开始借鉴他的亲戚,孩子,管家,邻居,殖民者,甚至前船友收集的信息[84]。而且从一开始,他就将人类包括在内。1838年3月28日,他在动物园里看到猩猩时,便注意到了它们的幼稚行为[85]。

The strain took a toll, and by June he was being laid up for days on end with stomach problems, headaches and heart symptoms. For the rest of his life, he was repeatedly incapacitated with episodes of stomach pains, vomiting, severe boils, palpitations, trembling and other symptoms, particularly during times of stress, such as attending meetings or making social visits. The cause of Darwin's illness remained unknown, and attempts at treatment had only ephemeral success.[86]

过度劳累造成了他一身的疾病,直至6月,他因胃病,头痛和心脏病不得不连续数天休息。在他的余生中,他也屡次因病痛而丧失行动能力,包括胃痛,呕吐,疖疮,、心悸颤抖和其他症状,尤其是在紧张的时期,例如参加会议或社交访问的时候。达尔文病灶仍然未知,那些治疗尝试只能暂时缓解他的病痛。[86]

On 23 June, he took a break and went "geologising" in Scotland. He visited Glen Roy in glorious weather to see the parallel "roads" cut into the hillsides at three heights. He later published his view that these were marine raised beaches, but then had to accept that they were shorelines of a proglacial lake.[87]

6月23日,他正好在休假,顺便苏格兰进行了“地理信息处理”。他在晴朗的天气里参观了格伦·罗伊Glen Roy,看到平行的“道路”从三个高度切入山坡。后来,他发表了自己的观点,认为这些是海上凸起的海滩,但随后不得不接受它们是冰川湖的海岸线。[87]

Fully recuperated, he returned to Shrewsbury in July. Used to jotting down daily notes on animal breeding, he scrawled rambling thoughts about marriage, career and prospects on two scraps of paper, one with columns headed "Marry" and "Not Marry". Advantages under "Marry" included "constant companion and a friend in old age ... better than a dog anyhow", against points such as "less money for books" and "terrible loss of time."[88] Having decided in favour of marriage, he discussed it with his father, then went to visit his cousin Emma on 29 July. He did not get around to proposing, but against his father's advice he mentioned his ideas on transmutation.[89]

后来待他完全康复,于七月回到什鲁斯伯里。因为他过去有习惯记下有关动物育种的记录,因此我们看到了他在两张纸上也草草地写下了他对于婚姻,职业和前景的漫长思考,其中一栏的标题为“结婚”和“不结婚”。在“结婚”下面写下了其好处为:“长久不变的同伴和朋友……总之比狗好”,坏处是“没有足够的钱买书”和“可怕的时间浪费”[88]。在决定结婚后,他与父亲讨论了结婚事宜,然后于7月29日去拜访表姐爱玛Emma。他没有抽空去准备该如何求婚,而是不顾父亲的劝告,提出了自己对于研究演变的想法计划。[89]

马尔萨斯与自然选择

Continuing his research in London, Darwin's wide reading now included the sixth edition of Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population, and on 28 September 1838 he noted its assertion that human "population, when unchecked, goes on doubling itself every twenty five years, or increases in a geometrical ratio", a geometric progression so that population soon exceeds food supply in what is known as a Malthusian catastrophe. Darwin was well prepared to compare this to de Candolle's "warring of the species" of plants and the struggle for existence among wildlife, explaining how numbers of a species kept roughly stable. As species always breed beyond available resources, favourable variations would make organisms better at surviving and passing the variations on to their offspring, while unfavourable variations would be lost. He wrote that the "final cause of all this wedging, must be to sort out proper structure, & adapt it to changes", so that "One may say there is a force like a hundred thousand wedges trying force into every kind of adapted structure into the gaps of in the economy of nature, or rather forming gaps by thrusting out weaker ones."[11][90] This would result in the formation of new species.[11][91] As he later wrote in his Autobiography:

后来达尔文继续在伦敦进行研究,他广泛阅读相关著作,包括马尔萨斯的《 人口原理An Essay on the Principle of Population 》第六版。1838年9月28日,他指出“人类的人口在不受控制的情况下每25年就会增加一倍,或者以几何比例增加”,这种呈几何级数增长的速度,会造成所谓的马尔萨斯灾难,人口很快会超出了粮食供应的极限。达尔文已做好充分的准备,可以将其与坎多尔Candolle的“物种争斗”进行比较,以及野生动植物之间为生存而进行的斗争,这解释了一个物种的数量是如何大致保持稳定。由于物种的繁殖总是超出可用资源,那么有利的变异将使生物能更好地生存下来并将变异传给其后代,而不利的变异将逐渐消失。他写道,“所有楔入的最终原因,必须是找出适当的结构,并使之适应变化”,因此,“有人可能会说有十万个楔形力,试图将各种适应力推向自然经济的缝隙,或者更精确地说通过淘汰弱者来形成这种缝隙。”[11][90] 这最终将导致新物种的形成。[11][91] 正如他后来在自传中写道:

In October 1838, that is, fifteen months after I had begun my systematic enquiry, I happened to read for amusement Malthus on Population, and being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence which everywhere goes on from long-continued observation of the habits of animals and plants, it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here, then, I had at last got a theory by which to work...[92]

在1838年10月,也就是我开始进行系统性调查的15个月后,我碰巧读了马尔萨斯的《人口原理》,通过长期不断地观察动植物的习性,做好了充分的准备去欣赏生物为生存而奋斗的过程。令我惊讶的是,我发现在这种情况下,生物倾向于保留有利的变化,而摈弃掉不利的变化。其结果将可能是形成一个新物种。然后基于这个假设,我终于产生了一个可以为之展开研究的理论...[92]

By mid-December, Darwin saw a similarity between farmers picking the best stock in selective breeding, and a Malthusian Nature selecting from chance variants so that "every part of newly acquired structure is fully practical and perfected",[93] thinking this comparison "a beautiful part of my theory".[94] He later called his theory natural selection, an analogy with what he termed the "artificial selection" of selective breeding.[11]

到12月中旬,达尔文观察到农民在育种时往往会选择最佳种群,而马尔萨斯主张的从随机变体中进行选择,以使“新获得的结构的每个部分都完全实用且完善”[93]具有与之相似的逻辑,达尔文认为这两者之间的比较是“他理论中最有力的证据”[94]。后来他称其理论为自然选择,与他所谓的选择性育种的“人工选择”相类似。[11]

On 11 November, he returned to Maer and proposed to Emma, once more telling her his ideas. She accepted, then in exchanges of loving letters she showed how she valued his openness in sharing their differences, also expressing her strong Unitarian beliefs and concerns that his honest doubts might separate them in the afterlife.[95] While he was house-hunting in London, bouts of illness continued and Emma wrote urging him to get some rest, almost prophetically remarking "So don't be ill any more my dear Charley till I can be with you to nurse you." He found what they called "Macaw Cottage" (because of its gaudy interiors) in Gower Street, then moved his "museum" in over Christmas. On 24 January 1839, Darwin was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS).[1][96]

11月11日,他回到梅尔,向艾玛求婚,再次向她讲述了自己的想法。她接受了他的求婚,然后在交换情书中展示了她如何珍视他的坦诚。他们开始分享彼此的分歧,艾玛也表达了她强烈的一神论信仰,并担心他的坦诚和怀疑可能会导致在来世[95]他们的分开。当他在伦敦寻找房子时,疾病不断发作,艾玛尽力说服让他休息一下,几乎预言到:“直到我能和你在一起照顾你之前,别再生病了。他在高尔街Gower Street找到了他们所谓的“金刚鹦鹉小屋”(由于其华丽的内饰),然后在圣诞节期间将他的“博物馆”搬进了他的家。1839年1月24日,达尔文被选为英国皇家学会FRS的研究员。[1][96]

On 29 January, Darwin and Emma Wedgwood were married at Maer in an Anglican ceremony arranged to suit the Unitarians, then immediately caught the train to London and their new home.[97]

1月29日,达尔文和艾玛·韦奇伍德在梅尔的一神论者英国国教仪式中结婚,然后立即乘火车前往他们在伦敦的新家。[97]

地质书籍,藤壶,进化研究

Darwin now had the framework of his theory of natural selection "by which to work",[92] as his "prime hobby".[98] His research included extensive experimental selective breeding of plants and animals, finding evidence that species were not fixed and investigating many detailed ideas to refine and substantiate his theory.[11] For fifteen years this work was in the background to his main occupation of writing on geology and publishing expert reports on the Beagle collections, and in particular, the barnacles.[99]

达尔文现在有了他的“主要兴趣”[98],即建立他自然选择理论“工作依据”[92]的框架。他的研究包括广泛的动植物选择性实验育种,寻找证据证明物种非永恒不变,并研究调查许多其他方法以完善和证实他的理论[11]。十五年来,他始终从事地质相关工作,并发表有关小猎犬号收集工作(特别是藤壶)的专家报告。[99]

When FitzRoy's Narrative was published in May 1839, Darwin's Journal and Remarks was such a success as the third volume that later that year it was published on its own.[100] Early in 1842, Darwin wrote about his ideas to Charles Lyell, who noted that his ally "denies seeing a beginning to each crop of species".[101]

1839年5月,费兹罗伊的《叙事Narrative》出版,达尔文的第三卷《纪录与评论Darwin's Journal and Remarks》取得了巨大的成功,并于当年下半年独立发行[100]。早在1842年,达尔文就向查尔斯·莱尔写下了他的想法,莱尔当时指出他的盟友“否认看到每种生物都有各自的原始祖先”。[101]

Darwin's book The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs on his theory of atoll formation was published in May 1842 after more than three years of work, and he then wrote his first "pencil sketch" of his theory of natural selection.[102] To escape the pressures of London, the family moved to rural Down House in September.[103] On 11 January 1844, Darwin mentioned his theorising to the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, writing with melodramatic humour "it is like confessing a murder".[104][105] Hooker replied "There may in my opinion have been a series of productions on different spots, & also a gradual change of species. I shall be delighted to hear how you think that this change may have taken place, as no presently conceived opinions satisfy me on the subject."[106]

经过三年多的工作,达尔文于1842年5月出版了关于环礁形成理论的《珊瑚礁的结构和分布》一书,然后他完成了自然选择理论[102]第一卷的初稿。后来为了逃避伦敦的压力,一家人于9月搬到农村的Down House[103]。1844年1月11日,达尔文向植物学家约瑟夫·道尔顿·胡克Joseph Dalton Hooker提到了他的理论[104][105],并幽默地写着“这就像承认谋杀一样”。胡克回答说:“我认为可能在不同地点确有发生,而且物种也在逐渐变化。我很高兴听到您如何看待这种变化,因为目前没有其他设想能说得通。”[106]

By July, Darwin had expanded his "sketch" into a 230-page "Essay", to be expanded with his research results if he died prematurely.[107] In November, the anonymously published sensational best-seller Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation brought wide interest in transmutation. Darwin scorned its amateurish geology and zoology, but carefully reviewed his own arguments. Controversy erupted, and it continued to sell well despite contemptuous dismissal by scientists.[108][109]

同年七月,达尔文将他的“草图”扩大到了230页的“随笔”,如果他英年早逝[107],他的研究成果也将会被他人进一步扩展。十一月,一本匿名出版的畅销书《自然创造史的遗迹Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation》引起了人们对演变的广泛兴趣。达尔文蔑视其业余地质学和动物学说,但他也仔细审查了自己的论点。后来争议爆发了,尽管科学家轻蔑地驳回了争议,但这本书仍然畅销。[108][109]

Darwin completed his third geological book in 1846. He now renewed a fascination and expertise in marine invertebrates, dating back to his student days with Grant, by dissecting and classifying the barnacles he had collected on the voyage, enjoying observing beautiful structures and thinking about comparisons with allied structures.[110] In 1847, Hooker read the "Essay" and sent notes that provided Darwin with the calm critical feedback that he needed, but would not commit himself and questioned Darwin's opposition to continuing acts of creation.[111]

达尔文于1846年完成了他的第三本地质著作。他又重拾了在格兰特的学生时代对海洋无脊椎动物的热爱。他通过解剖和分类他在航行中收集的藤壶,观察其内部迷人的结构,开始思考和比较相关同类物种结构[110]。1847年,胡克阅读了达尔文的随笔,并给达尔文表达了他对此的反馈,其观点相对冷静且带有批判性,但的确是达尔文当下需要的。胡可并没有承诺,和质疑达尔文对继续创造行为的反对。[111]

In an attempt to improve his chronic ill health, Darwin went in 1849 to Dr. James Gully's Malvern spa and was surprised to find some benefit from hydrotherapy.[112] Then, in 1851, his treasured daughter Annie fell ill, reawakening his fears that his illness might be hereditary, and after a long series of crises she died.[113]

为了改善自己的慢性病病情,达尔文在1849年去了詹姆斯·古利James Gully医生的莫尔文水疗中心[112],并惊讶地发现水疗可以带来一些好处。然后,在1851年,他珍爱的女儿安妮Annie生病,重新唤醒了他对自己的病可能是遗传性疾病的恐惧,在经历了一系列病痛后,安妮去世了。[113]

In eight years of work on barnacles (Cirripedia), Darwin's theory helped him to find "homologies" showing that slightly changed body parts served different functions to meet new conditions, and in some genera he found minute males parasitic on hermaphrodites, showing an intermediate stage in evolution of distinct sexes.[114] In 1853, it earned him the Royal Society's Royal Medal, and it made his reputation as a biologist.[115] In 1854 he became a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London, gaining postal access to its library.[116] He began a major reassessment of his theory of species, and in November realised that divergence in the character of descendants could be explained by them becoming adapted to "diversified places in the economy of nature".[117]

在藤壶Cirripedia的八年研究中,达尔文的理论帮助他找到了“同源性Homologies”,即轻微地改变某些身体部位构造,以具有能适应新环境的不同功能,在某些生物属中,他发现雌雄同体上寄生有微小的雄性生物,这表明存在不同性别进化的中间阶段[114]。1853年,该研究为他赢得了英国皇家学会的皇家勋章,并因此赢得了生物学家的声誉[115]。1854年,他成为伦敦林奈学会Linnean Society的会员,并获得了其图书馆的邮政访问权[116]。他也开始重新评估他的物种理论,并在接下来的11月,意识到后代的性格差异可以通过他们适应“自然经济中的多元化环境”来解释。[117]

自然选择理论的公开发表

By the start of 1856, Darwin was investigating whether eggs and seeds could survive travel across seawater to spread species across oceans. Hooker increasingly doubted the traditional view that species were fixed, but their young friend Thomas Henry Huxley was still firmly against the transmutation of species. Lyell was intrigued by Darwin's speculations without realising their extent. When he read a paper by Alfred Russel Wallace, "On the Law which has Regulated the Introduction of New Species", he saw similarities with Darwin's thoughts and urged him to publish to establish precedence. Though Darwin saw no threat, on 14 May 1856 he began writing a short paper. Finding answers to difficult questions held him up repeatedly, and he expanded his plans to a "big book on species" titled Natural Selection, which was to include his "note on Man". He continued his researches, obtaining information and specimens from naturalists worldwide including Wallace who was working in Borneo. In mid-1857 he added a section heading; "Theory applied to Races of Man", but did not add text on this topic. On 5 September 1857, Darwin sent the American botanist Asa Gray a detailed outline of his ideas, including an abstract of Natural Selection, which omitted human origins and sexual selection. In December, Darwin received a letter from Wallace asking if the book would examine human origins. He responded that he would avoid that subject, "so surrounded with prejudices", while encouraging Wallace's theorising and adding that "I go much further than you."[118]

到1856年初,达尔文一直在研究卵和种子能够成功地跨越海水将物种传播到另一个大陆。胡克也越来越对传统观点 -- 即物种是恒定不变的 -- 产生怀疑。但是他们的年轻朋友托马斯·亨利·赫黎Thomas Henry Huxley仍然坚决反对物种的演变说。莱文对达尔文的猜测很感兴趣,但却没有意识到其影响。当他阅读到阿尔弗雷德·罗素·华莱士Alfred Russel Wallace的论文《论规范新物种介绍的法则》时,他看到了与达尔文思想的相似之处,并敦促他发表文章以确立优先地位。尽管达尔文没有看到任何威胁,但他于1856年5月14日开始写一篇简短的论文。寻找能解决困难问题的答案使他反复受挫,他将计划扩展到一本名为《 自然选择Natural Selection 》的“物种全科书”,其中包括他“关于人类的笔记”。他继续他的研究,从全球博物学家那里(包括在婆罗洲工作的华莱士)获得信息和标本。1857年,他添加了一个小节标题;“人类种族理论”,不过他并没有添加相关主题的文字。同年9月5日,达尔文向美国植物学家阿萨·格雷Asa Gray发送了他详细的想法概述,包括《自然选择》一书的摘要,其中省略了人类起源和性别选择。12月,达尔文收到了华莱士的来信,询问这本书是否会研究人类起源。他回答说,他会避免那个“充满偏见”的话题,同时达尔文鼓励华莱士的理论,并补充说“我比你走得更远。”[118]

Darwin's book was only partly written when, on 18 June 1858, he received a paper from Wallace describing natural selection. Shocked that he had been "forestalled", Darwin sent it on that day to Lyell, as requested by Wallace,[119][120] and although Wallace had not asked for publication, Darwin suggested he would send it to any journal that Wallace chose. His family was in crisis with children in the village dying of scarlet fever, and he put matters in the hands of his friends. After some discussion, with no reliable way of involving Wallace, Lyell and Hooker decided on a joint presentation at the Linnean Society on 1 July of On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection. On the evening of 28 June, Darwin's baby son died of scarlet fever after almost a week of severe illness, and he was too distraught to attend.[121]

1858年6月18日达尔文收到了华莱士的一篇关于自然选择的论文,当时他的论文才完成了部分。达尔文感到非常震惊,华莱士竟然领先了一步。不过达尔文当天应华莱士的要求将其发送给了莱尔[119][120] ,尽管华莱士没有要求出版,但达尔文建议莱尔将其发送给华莱士选择的任何期刊。他的家人后来因村庄里的孩子死于猩红热而陷入危机,因此他把事情交到了朋友手中。经过一番讨论,莱尔和胡克找不到可靠的方法让华莱士参与进来,他们决定于7月1日在林内学会上联合发表《 关于物种形成变种的趋势;以及通过自然选择方式使变种和物种永存On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection 》。6月28日晚上,达尔文的小儿子在经历了近一个星期的严重疾病后死于猩红热,此时达尔文心急如焚,无心参加发表会。[121]

There was little immediate attention to this announcement of the theory; the president of the Linnean Society remarked in May 1859 that the year had not been marked by any revolutionary discoveries.[122] Only one review rankled enough for Darwin to recall it later; Professor Samuel Haughton of Dublin claimed that "all that was new in them was false, and what was true was old".[123] Darwin struggled for thirteen months to produce an abstract of his "big book", suffering from ill health but getting constant encouragement from his scientific friends. Lyell arranged to have it published by John Murray.[124]

当时该理论的宣布并没有立即引起注意;林内学会的主席在1859年5月表示,这一年没有任何革命性的发现。只有一项评论足以使达尔文后来回想起来。当时都柏林的塞缪尔·霍顿教授声称“其中所有的新理论[122]都是站不住脚的,而古老的思想才是真理”[123]。达尔文苦苦挣扎了十三个月来完成他的“全科书”的摘要,他虽然身体不好,期间受到了科学朋友的不断鼓励而一直持续创作,最终莱尔安排了由约翰·默里出版社出版。[124]

On the Origin of Species proved unexpectedly popular, with the entire stock of 1,250 copies oversubscribed when it went on sale to booksellers on 22 November 1859.[125] In the book, Darwin set out "one long argument" of detailed observations, inferences and consideration of anticipated objections.[126] In making the case for common descent, he included evidence of homologies between humans and other mammals.模板:Sfn模板:Ref label Having outlined sexual selection, he hinted that it could explain differences between human races.[127]模板:Ref label He avoided explicit discussion of human origins, but implied the significance of his work with the sentence; "Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."[128]模板:Ref label His theory is simply stated in the introduction:

当时《物种起源》出人意料地受到欢迎,当它在1859年11月22日出售给书商时,其全部1,250册的库存都被超额认购。在书中,达尔文阐述了“一个长期论点”,表达了其详细的观察,推断和对预期异议的考虑[125]。在为共同祖先这一概念辩护时,他提供了人类与其他哺乳动物之间同源性的证据[127]。在概述了性选择之后,他暗示这可以解释人类之间的差异。他避免了对人类起源的明确讨论,但用句子隐晦地表达了他工作的重要性[128]。“光将照耀着人类的起源及其历史。”引言中他简单地陈述了其理论:

As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary however slightly in any manner profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving, and thus be naturally selected. From the strong principle of inheritance, any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form.[129]

每个物种出生的个体比存活的个体多得多。因此,每个个体都在为生存而进行反复的斗争,随之而来的是,在复杂的,时而变化的环境下,任何个体只要以某种对自己有利的方式进行变化,这样即能获得更高的生存机会,因此自然而然地被选择了。根据强大的遗传原则,任何经过自然选择的物种都倾向于传播其全新经过改进的形态。[129]

在这本书的结尾,他总结道:

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.[130]

这种生命观宏伟壮丽,它强而有力,起初以多种形式或一种形式来展现。当这颗“行星“围绕固定不变的万有引力定律旋转时,一切都开始的如此简单明了,随后便以无穷无尽的形式完成,并持续的发生进化演变,充满精彩和美妙。[130]

The last word was the only variant of "evolved" in the first five editions of the book. "Evolutionism" at that time was associated with other concepts, most commonly with embryological development, and Darwin first used the word evolution in The Descent of Man in 1871, before adding it in 1872 to the 6th edition of The Origin of Species.[131]

在该书的前五个版本中,最后一个词“进化evolved”是唯一修改过的。当时的“进化论”与其他概念有关,最常见的是与胚胎学发展有关,达尔文于1871年在《人类的由来The Descent of Man》中首次使用了进化一词,随后于1872年将其加入《物种起源》的第六版。[131]

《物种起源》的反响

The book aroused international interest, with less controversy than had greeted the popular and less scientific Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation.[132] Though Darwin's illness kept him away from the public debates, he eagerly scrutinised the scientific response, commenting on press cuttings, reviews, articles, satires and caricatures, and corresponded on it with colleagues worldwide.[133] The book did not explicitly discuss human origins,[128]模板:Ref label but included a number of hints about the animal ancestry of humans from which the inference could be made.[134] The first review asked, "If a monkey has become a man–what may not a man become?" and said it should be left to theologians as it was too dangerous for ordinary readers.[135] Amongst early favourable responses, Huxley's reviews swiped at Richard Owen, leader of the scientific establishment Huxley was trying to overthrow.[136] In April, Owen's review attacked Darwin's friends and condescendingly dismissed his ideas, angering Darwin,[137] but Owen and others began to promote ideas of supernaturally guided evolution. Patrick Matthew drew attention to his 1831 book which had a brief appendix suggesting a concept of natural selection leading to new species, but he had not developed the idea.[138]

《物种起源》引起了国际上的关注,不过与人们广泛关注《自然创造史的遗迹》相比[132],争议较少,不过科学性也不及后者。尽管达尔文的疾病使他远离了公开辩论,但他仍然热切地关注科学届的反应,如反馈新闻报道、评论、文章、讽刺作品和漫画等,并与世界各地的同事们进行沟通[133]。该书没有明确讨论人类的起源[128],但是暗含了一些关于人类动物血统的线索,可以从中进行推断。第一篇书评问道:“如果猴子变成了人,那么人不会变成什么?”,他说应该交给神学家,因为这对普通读者[135]来说太危险了[134]。在早期的积极回应中,赫胥黎的评论抨击了理查德·欧文Richard Owen,后者是赫胥黎试图推翻的科学机构的领导人[136]。4月,欧文的评论攻击了达尔文的朋友,并居高临下地摒弃了他的想法,这激怒了达尔文[137],但是欧文和其他人开始提倡超自然引导的进化思想。当时帕特里克·马修Patrick Matthew提请注意达尔文1831年的书,该书有一个简短的附录,提出了自然选择的概念,该概念导致了新物种的出现,不过当时他并未提出这个想法。[138]

The Church of England's response was mixed. Darwin's old Cambridge tutors Sedgwick and Henslow dismissed the ideas, but liberal clergymen interpreted natural selection as an instrument of God's design, with the cleric Charles Kingsley seeing it as "just as noble a conception of Deity".[139] In 1860, the publication of Essays and Reviews by seven liberal Anglican theologians diverted clerical attention from Darwin, with its ideas including higher criticism attacked by church authorities as heresy. In it, Baden Powell argued that miracles broke God's laws, so belief in them was atheistic, and praised "Mr Darwin's masterly volume [supporting] the grand principle of the self-evolving powers of nature".[140] Asa Gray discussed teleology with Darwin, who imported and distributed Gray's pamphlet on theistic evolution, Natural Selection is not inconsistent with natural theology.[139][141] The most famous confrontation was at the public 1860 Oxford evolution debate during a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, where the Bishop of Oxford Samuel Wilberforce, though not opposed to transmutation of species, argued against Darwin's explanation and human descent from apes. Joseph Hooker argued strongly for Darwin, and Thomas Huxley's legendary retort, that he would rather be descended from an ape than a man who misused his gifts, came to symbolise a triumph of science over religion.[139][142]

对此英格兰教会的反应好坏参半。达尔文的老剑桥导师塞奇威克Sedgwick和汉斯洛Henslow拒绝接受这些想法,但自由派牧师却将自然选择解释为上帝设计的工具,例如牧师查尔斯·金斯利Charles Kingsley则将其视为“与神一样崇高”[139]。1860年,七位自由派英国国教神学家发表了论文集和评论,转移了牧师对达尔文的关注,包括受到教会当局以异端邪说为由的极端批评。其中,巴登·鲍威尔Baden Powell辩称,是奇迹打破了上帝的律法,所以他们信仰无神论,并称赞“达尔文先生的著作非常透彻精妙,它为自然具有自我进化能力的基本原则提供了支持”[140]。阿萨·格雷Asa Gray与达尔文讨论了 目的论Teleology ,达尔文引入并分发了格雷关于神导进化论的小册子。自然选择与自然神学并不矛盾。另外最著名的交锋是在英国科学促进协会内部的一次会议上,在公开的1860年牛津进化辩论中,牛津大学的主教塞缪尔·威尔伯福斯Samuel Wilberforce虽然不反对物种演变,但他仍然驳斥达尔文对人类是猿类后裔这一解释。而约瑟夫·胡克则强烈主张达尔文,还有托马斯·赫胥黎,他最著名的反驳是,他宁愿是猿猴的后代,也不愿是滥用礼物的人,该比喻象征着科学战胜了宗教。[139][142]

Even Darwin's close friends Gray, Hooker, Huxley and Lyell still expressed various reservations but gave strong support, as did many others, particularly younger naturalists. Gray and Lyell sought reconciliation with faith, while Huxley portrayed a polarisation between religion and science. He campaigned pugnaciously against the authority of the clergy in education,[139] aiming to overturn the dominance of clergymen and aristocratic amateurs under Owen in favour of a new generation of professional scientists. Owen's claim that brain anatomy proved humans to be a separate biological order from apes was shown to be false by Huxley in a long running dispute parodied by Kingsley as the "Great Hippocampus Question", and discredited Owen.[143]

尽管达尔文的密友格雷、胡克、赫胥黎和莱尔仍然表示了对他理论的各种保留观点,但也给予了大力支持,另外许多人,尤其是年轻的博物学家也表示了支持。格雷和莱尔在寻求其与信仰能和谐存在的方式,而赫胥黎则描绘了宗教与科学之间的两极分化。他带有挑衅地反对神职人员在教育方面的权威[139],旨在推翻欧文领导下的牧师和贵族倾向者的统治,转而采用新一代的专业科学家。当时欧文想通过大脑解剖来证明了人类是与猿完全独立的物种,而赫胥黎在关于金斯利Kingsley提出的“海马体问题”的长期争议中证明了欧文的主张是错误的,并使欧文名誉扫地。[143]

Darwinism became a movement covering a wide range of evolutionary ideas. In 1863 Lyell's Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man popularised prehistory, though his caution on evolution disappointed Darwin. Weeks later Huxley's Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature showed that anatomically, humans are apes, then The Naturalist on the River Amazons by Henry Walter Bates provided empirical evidence of natural selection.[144] Lobbying brought Darwin Britain's highest scientific honour, the Royal Society's Copley Medal, awarded on 3 November 1864.[145] That day, Huxley held the first meeting of what became the influential "X Club" devoted to "science, pure and free, untrammelled by religious dogmas".[146] By the end of the decade most scientists agreed that evolution occurred, but only a minority supported Darwin's view that the chief mechanism was natural selection.[147]

其影响促使出现了达尔文主义,并成为涵盖广泛进化思想的运动。1863年,莱尔的《人类古代地质证据》普及了史前史,尽管他对进化论的谨慎使达尔文感到失望。几周后,赫胥黎的书《人类在自然界的位置》表明了证据,从解剖学上讲,人是猿,然后亨利·沃尔特·贝茨Henry Walter Bates的《亚马逊河上的博物学家》提供了自然选择[144]的经验依据。游说运动后来为达尔文带来了英国最高等级的科学荣誉,即皇家学会的科普利勋章,于1864年11月3日颁发[145]。那天,赫胥黎举行了第一次会议,这次会议成为了颇具影响力的“X俱乐部”,该俱乐部致力于宣扬“科学,纯净,自由,不受宗教教条约束”[146]。到本世纪末,大多数科学家同意进化理论,但是只有少数人支持达尔文的观点,即主要机制是自然选择。[147]

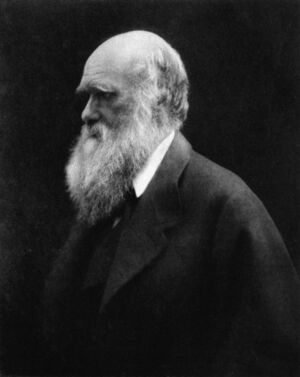

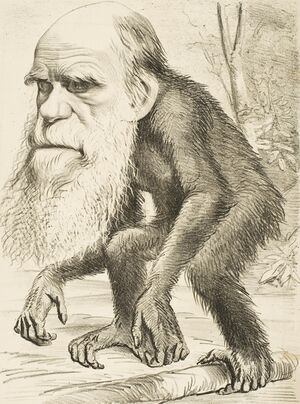

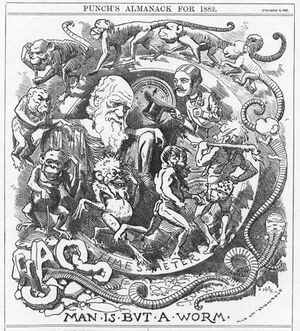

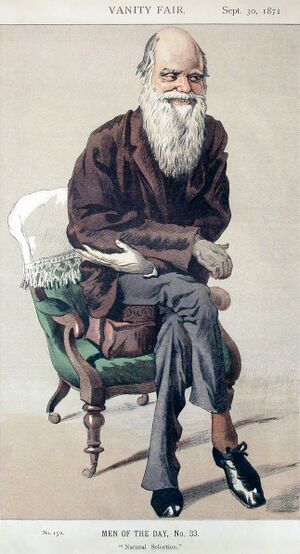

The Origin of Species was translated into many languages, becoming a staple scientific text attracting thoughtful attention from all walks of life, including the "working men" who flocked to Huxley's lectures.[148] Darwin's theory also resonated with various movements at the time模板:Ref label and became a key fixture of popular culture.模板:Ref label Cartoonists parodied animal ancestry in an old tradition of showing humans with animal traits, and in Britain these droll images served to popularise Darwin's theory in an unthreatening way. While ill in 1862 Darwin began growing a beard, and when he reappeared in public in 1866 caricatures of him as an ape helped to identify all forms of evolutionism with Darwinism.[149]

后来《物种起源》被翻译成了多种语言,成为一种非常重要的科学读物,引起了各行各业的关注,包括当时涌向赫胥黎演讲的“劳动者”。达尔文的理论在当时也引起了各种运动的共鸣,并成为流行文化的重要组成部分[148]。漫画家们通过夸张地演绎古老的动物祖先,以展示人类也具有动物的特征。在英国,这些滑稽的图像以一种毫无威胁的方式推广了达尔文的理论。在1862年生病期间,达尔文开始留胡子。1866年当他重新露面时,他的猿猴漫画帮助了他将达尔文主义所有形式的进化论定义出来。[149]

人类的由来,性别选择和植物学

Despite repeated bouts of illness during the last twenty-two years of his life, Darwin's work continued. Having published On the Origin of Species as an abstract of his theory, he pressed on with experiments, research, and writing of his "big book". He covered human descent from earlier animals including evolution of society and of mental abilities, as well as explaining decorative beauty in wildlife and diversifying into innovative plant studies.

尽管在他在生命的最后22年中疾病反复发作,达尔文的工作一直在继续。在发表了《物种起源》作为其理论的摘要之后,他继续进行实验,研究和撰写了他的“全科书”。他介绍了人类起源于较早的动物,包括社会和智力的发展,以及解释野生动植物的装饰之美,并进行多样化的新型植物研究。

Enquiries about insect pollination led in 1861 to novel studies of wild orchids, showing adaptation of their flowers to attract specific moths to each species and ensure cross fertilisation. In 1862 Fertilisation of Orchids gave his first detailed demonstration of the power of natural selection to explain complex ecological relationships, making testable predictions. As his health declined, he lay on his sickbed in a room filled with inventive experiments to trace the movements of climbing plants.[150] Admiring visitors included Ernst Haeckel, a zealous proponent of Darwinismus incorporating Lamarckism and Goethe's idealism.[151] Wallace remained supportive, though he increasingly turned to Spiritualism.[152]

他对昆虫授粉的研究推动了1861年对野生兰花进行的全新研究,结果表明它们的花体中同样具有适应性,花吸引特定的飞蛾进入每个物种并确保杂交。1862年,《 兰花的传粉Fertilisation of Orchids 》首次详细展示了自然选择的力量,书中解释了复杂的生态关系,并提供可验证的预测。随着健康状况的下降,达尔文躺在房间里的病床上,房间里充满了许多创造性的实验,追踪攀援植物的运动轨迹[150]。拜访者包括恩斯特·海克尔Ernst Haeckel,他是达尔文主义的热心拥护者,融合了拉马克主义和歌德的理想主义[151]。尽管他越来越转向唯心论,华莱士仍然选择支持他。[152]

Darwin's book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868) was the first part of his planned "big book", and included his unsuccessful hypothesis of pangenesis attempting to explain heredity. It sold briskly at first, despite its size, and was translated into many languages. He wrote most of a second part, on natural selection, but it remained unpublished in his lifetime.[153]

达尔文的著作《动物和植物在家养下的变异The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication》(1868年)是他计划中的“全科书”的第一部分,包括他试图解释遗传,但是未能成功的提出一个合理的假说。“全科书”的规模很大,一开始就卖得很快,并被翻译成多种语言。之后他写的第二部分则大部分是关于自然选择的,但最终未能出版。[153]

Lyell had already popularised human prehistory, and Huxley had shown that anatomically humans are apes.[144] With The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex published in 1871, Darwin set out evidence from numerous sources that humans are animals, showing continuity of physical and mental attributes, and presented sexual selection to explain impractical animal features such as the peacock's plumage as well as human evolution of culture, differences between sexes, and physical and cultural racial classification, while emphasising that humans are all one species.[154] His research using images was expanded in his 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, one of the first books to feature printed photographs, which discussed the evolution of human psychology and its continuity with the behaviour of animals. Both books proved very popular, and Darwin was impressed by the general assent with which his views had been received, remarking that "everybody is talking about it without being shocked."[155] His conclusion was "that man with all his noble qualities, with sympathy which feels for the most debased, with benevolence which extends not only to other men but to the humblest living creature, with his god-like intellect which has penetrated into the movements and constitution of the solar system—with all these exalted powers—Man still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin."[156]

莱尔普及了人类史,赫胥黎则从解剖学上证明了人类是猿。达尔文在1871年出版的《 人类的由来及性选择The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex 》一书中,收集了大量证据来证明人类是动物 [144]-- 无论是生理上还是心理上的进化的连续性。并提出可以用性选择来解释无法说通的动物特征区别,例如孔雀的羽毛以及人类的文化演变,性别差异以及生理和文化种族的分类,同时他还强调所有人类都源于一个物种[154]。他的影像研究在1872年出版的《 人与动物的情感表达The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals 》一书中得到了扩展,这是最早印有印刷照片的书籍之一,该书讨论了人类心理的演变及其与动物行为的连续性。这两本书都非常受欢迎,达尔文因此特别感动,因为他的观点得到普遍认可,特别是“每个人都在谈论它,并不会感到震惊”[155]。他总结道“他具有所有的高尚品格,充满同情心(即使是对最低贱的生物),他的仁爱不仅适用于他人,也适用于最卑微的生灵,他的神性智慧已经渗透到行动中。太阳系的构成(包括所有这些崇高的力量),都使人类在肉体中烙印上他出身低微且不可磨灭的印记。”[156]

His evolution-related experiments and investigations led to books on Orchids, Insectivorous Plants, The Effects of Cross and Self Fertilisation in the Vegetable Kingdom, different forms of flowers on plants of the same species, and The Power of Movement in Plants. He continued to collect information and exchange views from scientific correspondents all over the world, including Mary Treat, whom he encouraged to persevere in her scientific work.[157] His botanical work模板:Ref label was interpreted and popularised by various writers including Grant Allen and H. G. Wells, and helped transform plant science in the late 19th century and early 20th century. In his last book he returned to The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms.

达尔文依据这些与进化有关的实验研究还撰写出关于兰花的书籍,《 食虫植物Insectivorous Plants 》,《 异花授精与自体授精在植物界中的效果The Effects of Cross and Self-Fertilisation in the Vegetable Kingdom 》,《 同种植物的不同花型The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species 》,《 植物运动的力量The Power of Movement in Plants 》。他继续从全世界的科学记者那里收集信息并交流观点,像是玛丽·特里特Mary Treat,达尔文曾鼓励她坚持不懈地从事科学工作[157]。达尔文的植物学著作后来还得到了格兰特·艾伦Grant Allen和H·G·威尔斯H. G. Wells等众多作家的诠释和推广,并在19世纪后期和20世纪初推动了植物科学的发展。最后,他完成了《腐植土的产生与蚯蚓的作用》。

逝世及葬礼

In 1882 he was diagnosed with what was called "angina pectoris" which then meant coronary thrombosis and disease of the heart. At the time of his death, the physicians diagnosed "anginal attacks", and "heart-failure".[158] It has been speculated that Darwin may have suffered from chronic Chagas disease.[159] This speculation is based on a journal entry written by Darwin, describing he was bitten by the "Kissing Bug" in Mendoza, Argentina, in 1835;[160] and based on the constellation of clinical symptoms he exhibited, including cardiac disease which is a hallmark of chronic Chagas disease.[161][159] Exhuming Darwin's body is likely necessary to definitively determine his state of infection by detecting DNA of infecting parasite, T. cruzi, that causes Chagas disease.[159][160]

1882年,达尔文被诊断出患有“心绞痛”,即冠状动脉血栓和心脏疾病。在他去世时,医生诊断为“心绞痛”和“心脏衰竭”。据推测,达尔文可能患有慢性锥虫病。这种猜测基于达尔文写的日记,他曾描述过1835年在阿根廷门多萨被“猎蝽”咬伤;同时也可以根据他表现出的临床症状来推断,例如心脏病就是一种慢性锥虫病的症状。当然如有必要可以挖掘出达尔文的尸体,通过检测一种可以导致锥虫病克氏锥虫的寄生虫的DNA来确定其是否被感染。

He died at Down House on 19 April 1882. His last words were to his family, telling Emma "I am not the least afraid of death—Remember what a good wife you have been to me—Tell all my children to remember how good they have been to me", then while she rested, he repeatedly told Henrietta and Francis "It's almost worth while to be sick to be nursed by you".[162] He had expected to be buried in St Mary's churchyard at Downe, but at the request of Darwin's colleagues, after public and parliamentary petitioning, William Spottiswoode (President of the Royal Society) arranged for Darwin to be honoured by burial in Westminster Abbey, close to John Herschel and Isaac Newton. The funeral was held on Wednesday 26 April and was attended by thousands of people, including family, friends, scientists, philosophers and dignitaries.[163][8]

达尔文于1882年4月19日在Down House逝世。在他遗言中,他对艾玛说道:“我一点也不害怕死亡。记住对我来说你是个好妻子,告诉我所有的孩子,记住他们对我有多好”。在她休息的时候,他反复告诉亨利埃塔和弗朗西斯:“我由你来照顾是多么的值得”。[162]他原本希望被葬在郡达温的圣玛丽墓地,但由于达尔文的同事请求,和议会通过的公开请愿,由威廉·斯波提斯伍德William Spottiswoode(皇家学会主席)安排了为他威斯敏斯特大教堂进行葬礼,那里靠近约翰·赫歇尔和艾萨克·牛顿。他的葬礼于4月26日星期三举行,有成千上万的人参加,包括家人,朋友,科学家,哲学家和政要。[163][8]

学术遗产

By the time of his death, Darwin and his colleagues had convinced most scientists that evolution as descent with modification was correct, and he was regarded as a great scientist who had revolutionised ideas. In June 1909, though few at that time agreed with his view that "natural selection has been the main but not the exclusive means of modification", he was honoured by more than 400 officials and scientists from across the world who met in Cambridge to commemorate his centenary and the fiftieth anniversary of On the Origin of Species.[164] Around the beginning of the 20th century, a period that has been called "the eclipse of Darwinism", scientists proposed various alternative evolutionary mechanisms, which eventually proved untenable. Ronald Fisher, an English statistician, finally united Mendelian genetics with natural selection, in the period between 1918 and his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection.[165] He gave the theory a mathematical footing and brought broad scientific consensus that natural selection was the basic mechanism of evolution, thus founding the basis for population genetics and the modern evolutionary synthesis, with J.B.S. Haldane and Sewall Wright, which set the frame of reference for modern debates and refinements of the theory.[12]

在他去世前,达尔文和他的同事已经说服了大多数科学家,进化作为 后代渐变Descent with modification这一概念是准确无误的。他也因彻底改变了人们固有的生物进化理念被认为是伟大的科学家。1909年6月,尽管当时很少有人同意“自然选择是主要但非排他性的后代渐变手段”这一观点,但达尔文受到了世界各地400多名官员和科学家的赞同,他们甚至在剑桥为他举行仪式来纪念他的百年诞辰和《物种起源》[164]出版五十周年。大约在20世纪初,即所谓的“达尔文主义消亡”时期,科学家们提出了各种能替代自然选择的进化机制,但最终均被证明站不住脚。英国统计学家罗纳德•费舍尔Ronald Fisher在1918年至1930年的著作《 自然选择的遗传学理论The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection 》[165],终于将孟德尔遗传学与自然选择结合起来。他为该理论提供了数学基础,并引起广泛的科学共识,即自然选择是进化的基本机制,从而为人类遗传学和现代进化综合奠定了基础。霍尔丹Haldane和塞沃尔•赖特Sewall Wright为现代辩论和对该理论的完善设定了参考框架。[12]

纪念活动

During Darwin's lifetime, many geographical features were given his name. An expanse of water adjoining the Beagle Channel was named Darwin Sound by Robert FitzRoy after Darwin's prompt action, along with two or three of the men, saved them from being marooned on a nearby shore when a collapsing glacier caused a large wave that would have swept away their boats,[166] and the nearby Mount Darwin in the Andes was named in celebration of Darwin's 25th birthday.[167] When the Beagle was surveying Australia in 1839, Darwin's friend John Lort Stokes sighted a natural harbour which the ship's captain Wickham named Port Darwin: a nearby settlement was renamed Darwin in 1911, and it became the capital city of Australia's Northern Territory.[168]

达尔文在世时,许多地理特征都以他的名字命名。在比格海峡Beagle Channel旁的一片广阔水域,曾发生冰川坍塌,达尔文当即与一起同行的两三个人采取行动,使他们的船免于被因坍塌的冰川造成的海浪冲走[166],从而避免了他们被困在附近的海岸。后来罗伯特•菲茨•罗伊Robert FitzRoy就将这片水域命名为达尔文海峡Darwin Sound。为了庆祝达尔文诞辰25周年[167],附近的安第斯山脉也被命名为达尔文山。当猎犬号在1839年对澳大利亚进行勘测时,达尔文的朋友约翰•洛特•斯托克斯John Lort Stokes看到了一个天然海港,船长威克汉姆Wickham将其命名为达尔文港:而附近的一个定居点于1911年更名为达尔文,后来它成为了澳大利亚北领地的首府。[168]

Stephen Heard identified 389 species that have been named after Darwin,[169] and there are at least 9 genera.[170] In one example, the group of tanagers related to those Darwin found in the Galápagos Islands became popularly known as "Darwin's finches" in 1947, fostering inaccurate legends about their significance to his work.[171]

斯蒂芬•希德Stephen Heard确定了至少9个属389个以达尔文命名的物种[169]。例如,与达尔文在加拉帕戈斯群岛中的发现有关的唐纳雀[170],在1947年被广泛称为“达尔文雀”。据不准确传闻,这是为了纪念这群雀类对达尔文研究工作的意义[171]。

Darwin's work has continued to be celebrated by numerous publications and events. The Linnean Society of London has commemorated Darwin's achievements by the award of the Darwin–Wallace Medal since 1908. Darwin Day has become an annual celebration, and in 2009 worldwide events were arranged for the bicentenary of Darwin's birth and the 150th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of Species.[172]

达尔文的工作持续受到大量出版社和活动的青睐。自1908年以来,伦敦林奈学会就通过颁发达尔文-华莱士奖章来纪念达尔文的成就。达尔文纪念日已成为一年一度的庆祝活动,2009年,在达尔文诞辰200周年和《物种起源》出版150周年之际,人们还举行了全球性庆祝活动。[172]

Darwin has been commemorated in the UK, with his portrait printed on the reverse of £10 banknotes printed along with a hummingbird and HMS Beagle, issued by the Bank of England.[173]

为了纪念达尔文,英国将他的肖像印在了10英镑钞票的反面,并印有英国银行发行的蜂鸟和猎犬号。[173]

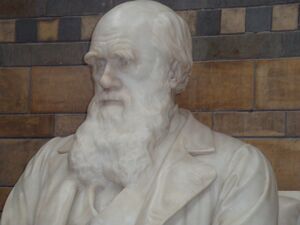

A life-size seated statue of Darwin can be seen in the main hall of the Natural History Museum in London.[174]

在伦敦自然历史博物馆的正厅可以看到真人大小的达尔文坐像。[174]

A seated statue of Darwin, unveiled 1897, stands in front of Shrewsbury Library, the building that used to house Shrewsbury School, which Darwin attended as a boy. Another statue of Darwin as a young man is situated in the grounds of Christ's College, Cambridge.

在什鲁斯伯里图书馆的前面耸立着一座坐着的达尔文雕像,该雕像于1897年揭幕,什鲁斯伯里图书馆曾经是什鲁斯伯里学校的所在地,达尔文还是孩子的时候曾就读于此。达尔文年轻时的另一尊雕像则位于剑桥基督学院。

Darwin College, a postgraduate college at Cambridge University, is named after the Darwin family.[175]

剑桥大学研究生院达尔文学院以达尔文家族的名字命名。[175]

In 2008–09, the Swedish band The Knife, in collaboration with Danish performance group Hotel Pro Forma and other musicians from Denmark, Sweden and the US, created an opera about the life of Darwin, and The Origin of Species, entitled Tomorrow, in a Year. The show toured European theatres in 2010.

在2008-09年,瑞典乐队The Knife,丹麦表演团体Hotel Pro Forma与其他来自丹麦、瑞典和美国的音乐家们合作,创作了一部关于达尔文的生活和《物种起源》的歌剧,叫《 一年后的明天Tomorrow, in a Year 》

达尔文的孩子

| William Erasmus | 27 December 1839 – | 8 September 1914 |

| Anne Elizabeth | 2 March 1841 – | 23 April 1851 |

| Mary Eleanor | 23 September 1842 – | 16 October 1842 |

| Henrietta Emma | 25 September 1843 – | 17 December 1927 |

| George Howard | 9 July 1845 – | 7 December 1912 |

| Elizabeth | 8 July 1847 – | 8 June 1926 |

| Francis | 16 August 1848 – | 19 September 1925 |

| Leonard | 15 January 1850 – | 26 March 1943 |

| Horace | 13 May 1851 – | 29 September 1928 |

| Charles | 6 December 1856 – | 28 June 1858 |

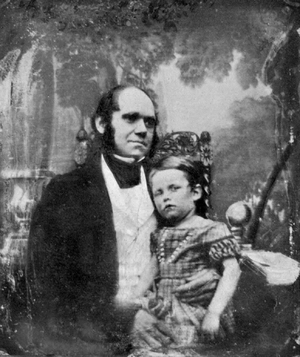

The Darwins had ten children: two died in infancy, and Annie's death at the age of ten had a devastating effect on her parents. Charles was a devoted father and uncommonly attentive to his children.[15] Whenever they fell ill, he feared that they might have inherited weaknesses from inbreeding due to the close family ties he shared with his wife and cousin, Emma Wedgwood.

达尔文夫妇有十个孩子:其中两个婴儿早夭,一个女儿安妮十岁的时候去世,这对他们夫妻二人造成了毁灭性的影响。查尔斯是位虔诚的父亲,对他的孩子们特别关心[15]。每当他们生病时,达尔文都担心是由于自己和同为表姐的妻子,爱玛·韦奇伍德的近亲关系可能会导致下一代从近亲交配中继承弱点。

He examined inbreeding in his writings, contrasting it with the advantages of outcrossing in many species.模板:Sfn Despite his fears, most of the surviving children and many of their descendants went on to have distinguished careers.

他在作品中研究了近亲交配,并将其与异种杂交的优势进行了对比。尽管他很担心,不过他大多数幸存的孩子和他们的许多后代仍然非常优秀,事业有成。

Of his surviving children, George, Francis and Horace became Fellows of the Royal Society,[176] distinguished as astronomer,[177] botanist and civil engineer, respectively. All three were knighted. Another son, Leonard, went on to be a soldier, politician, economist, eugenicist and mentor of the statistician and evolutionary biologist Ronald Fisher.[178]

在其幸存的孩子中,乔治,弗朗西斯和霍拉斯[176],分别以天文学家[177],植物学家和土木工程师的身份成为皇家学会会员,且三个人都被封为爵士[179]。而另一个儿子伦纳德则前后担任了士兵、政治家、经济学家、优生主义者和统计学家、进化生物学家罗纳德·费希尔的导师。[178]

观点和看法

宗教观

Darwin's family tradition was nonconformist Unitarianism, while his father and grandfather were freethinkers, and his baptism and boarding school were Church of England.[25] When going to Cambridge to become an Anglican clergyman, he did not doubt the literal truth of the Bible.[33] He learned John Herschel's science which, like William Paley's natural theology, sought explanations in laws of nature rather than miracles and saw adaptation of species as evidence of design.[35][36] On board HMS Beagle, Darwin was quite orthodox and would quote the Bible as an authority on morality.[180] He looked for "centres of creation" to explain distribution,[59] and suggested that the very similar antlions found in Australia and England were evidence of a divine hand.[61]

达尔文的家庭传统并不墨守成规,他们是一神论的拥护者,而且他的父亲和祖父是自由思想家,但是为他洗礼以及他日后上的寄宿学校所属却是英格兰教会[25]。当他去剑桥成为英国国教牧师时,他将圣经[33]奉为圭臬。但在他学习了约翰·赫歇尔John Herschel的科学后,正如威廉·佩利William Paley的自然神学一样,他寻求自然规律而不是一些自圆其说的解释,并将物种的适应性视为自然设计的证据。[35][36] 在猎犬号上,达尔文颇为正统,他将圣经视为道德权威。他曾试图寻找“创造中心”来解释其物种的分布,并提出观点,称在澳大利亚和英国发现的非常相似的蚁群其实是神之所作的证据。

By his return, he was critical of the Bible as history, and wondered why all religions should not be equally valid.[180] In the next few years, while intensively speculating on geology and the transmutation of species, he gave much thought to religion and openly discussed this with his wife Emma, whose beliefs also came from intensive study and questioning.[95] The theodicy of Paley and Thomas Malthus vindicated evils such as starvation as a result of a benevolent creator's laws, which had an overall good effect. To Darwin, natural selection produced the good of adaptation but removed the need for design,[181] and he could not see the work of an omnipotent deity in all the pain and suffering, such as the ichneumon wasp paralysing caterpillars as live food for its eggs.[141] Though he thought of religion as a tribal survival strategy, Darwin was reluctant to give up the idea of God as an ultimate lawgiver. He was increasingly troubled by the problem of evil.[182][183]

回国后,他对人们将圣经作为史实的观念进行了批判,并试图解释为什么所有宗教都不应该有根有据[180]。接下来的几年中,在深入推测地质和物种演变的同时,他对宗教也进行了诸多思考。他与妻子艾玛公开讨论了这一点,艾玛的信仰也来自于深入的研究和质疑[95]。佩利和托马斯·马尔萨斯的神学论证了诸如饥饿之类的邪恶存在,其实是由仁慈的创造者定律所带来的,该理论总体上产生了良好的效果。对达尔文而言,自然选择带来了适用能力的好处,但消除了设计这个概念的需要[181],他看不到无所不能的神在所有痛苦和苦难中工作,例如鱼龙黄蜂麻痹了毛毛虫,将其作为卵的活食[141]。尽管达尔文认为宗教是作为部落生存的策略而存在,但他并不愿意放弃将上帝视为终极立法者的想法。他越来越受到罪恶问题的困扰。[182][183]

Darwin remained close friends with the vicar of Downe, John Brodie Innes, and continued to play a leading part in the parish work of the church,[184] but from around 1849 would go for a walk on Sundays while his family attended church.[185] He considered it "absurd to doubt that a man might be an ardent theist and an evolutionist"[186][187] and, though reticent about his religious views, in 1879 he wrote that "I have never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of a God. – I think that generally ... an agnostic would be the most correct description of my state of mind".[95][186]

达尔文与郡达温牧师约翰·布罗迪·英内斯John Brodie Innes保持着密切的朋友关系,并继续在教堂的教区工作中发挥重要作用[184]。但从1849年左右起,当他的家人在周日去教堂做礼拜时,他更愿意选择散步。他认为“怀疑一个人即可能是一个热情的有神论者,同时也是进化论者是荒谬的”[186][187] 。尽管对宗教观点他一直保持沉默,但在1879年,他写道:“从否认上帝存在的意义上说,我从来不是无神论者。“从拒绝上帝存在的意义上说,我从来没有做过无神论者。–我认为……一般而言,不可知论者是对我心态最正确的描述”。[95][186]

The "Lady Hope Story", published in 1915, claimed that Darwin had reverted to Christianity on his sickbed. The claims were repudiated by Darwin's children and have been dismissed as false by historians.[188]

1915年出版的《 霍普夫人的故事Lady Hope Story 》中声称达尔文在病床上重回了基督教信仰。该说法后来被达尔文的孩子们否定,并被历史学家认定为虚假信息。[188]

人类社会

Darwin's views on social and political issues reflected his time and social position. He grew up in a family of Whig reformers who, like his uncle Josiah Wedgwood, supported electoral reform and the emancipation of slaves. Darwin was passionately opposed to slavery, while seeing no problem with the working conditions of English factory workers or servants. His taxidermy lessons in 1826 from the freed slave John Edmonstone, whom he long recalled as "a very pleasant and intelligent man", reinforced his belief that black people shared the same feelings, and could be as intelligent as people of other races. He took the same attitude to native people he met on the Beagle voyage.模板:Sfn These attitudes were not unusual in Britain in the 1820s, much as it shocked visiting Americans. British society started to envisage racial differences more vividly in mid-century,[26] but Darwin remained strongly against slavery, against "ranking the so-called races of man as distinct species", and against ill-treatment of native people.[189]模板:Ref label Darwins interaction with Yaghans (Fuegians) such as Jemmy Button during the second voyage of HMS Beagle had a profound impact on his view of primitive peoples. At his arrival to Tierra del Fuego he made a colourful description of "Fuegian savages".[190] This view changed as he came to know Yaghan people more in detail. By studying the Yaghans, Darwin concluded that a number of basic emotions by different human groups were the same and that mental capabilities were roughly the same as for Europeans.[190] While interested in Yaghan culture Darwin failed to appreciate their deep ecological knowledge and elaborate cosmology until the 1850s when he inspected a dictionary of Yaghan detailing 32-thousand words.[190] He saw that European colonisation would often lead to the extinction of native civilisations, and "tr[ied] to integrate colonialism into an evolutionary history of civilization analogous to natural history."

达尔文对社会和政治问题的看法也反映出了他的时代背景和社会地位。他在辉格党改革派家庭中长大,像他的叔叔乔西亚·韦奇伍德一样,他支持选举改革和奴隶的解放。达尔文满腔热情地反对奴隶制,但却认为英国工厂工人或仆人的工作条件并不存在问题。他在1826年从被释放的奴隶约翰·埃德蒙斯通那里学到了如何剥制动物标本,达尔文一直记得他是“一个非常讨人喜欢且聪明的人”,这进一步强化了他的信念,即黑人具有相同的感受,并且可能与其他种族的人一样聪明。他对猎犬号航行中遇到的土著人持同样的态度。这些态度在1820年代的英国并不罕见,但是这却让来访的美国人感到震惊。英国社会在本世纪中叶[26]开始更加着重强调种族差异,但达尔文仍然坚决反对奴隶制,反对“将所谓的人类种族列为不同的种族”,并反对虐待土著人民[189]。在猎犬号第二次航行中,达尔文与亚格汉的人(火地岛人),例如杰米·巴顿进行互动,这个经历使他对原始民族的看法产生了深远的影响。到达火地岛时,他对“火地岛野蛮人”做了丰富多彩的描述。当他更加详细地了解亚格汉人时,这种看法发生了变化。通过研究亚格汉人,达尔文得出结论,不同人类群体的许多基本情感是相同的,并且心理能力与欧洲人大致相同[190]。达尔文虽然对亚格汉文化产生了兴趣,但直到1850年代,他查阅了亚格汉词典,其中详细列出了32,000个单词[190],也正是到了那时,他才对它们深厚的生态知识和复杂的宇宙学感兴趣。[191]

他认为男人优于女人是性别选择的结果,Antoinette Brown Blackwell在1875年出版的《大自然中的性别 The Sexes Throughout Nature》一书中对此观点提出了质疑。[192]

达尔文对表兄弟弗朗西斯·高尔顿Francis Galton在1865年提出的论点深感兴趣,弗朗西斯认为,通过遗传的统计分析,可以表明道德和精神上的人类特征可以被继承,并且动物繁殖的原理也可以适用于人类。达尔文在《人类的由来》中指出,帮助弱者生存并使之拥有家庭,可能会失去自然选择带来的好处,但他又警告说,拒绝提供援助将磨灭人类同情的本性,即“我们本性中最崇高的部分”,他认为诸如教育之类的因素可能更为重要。当高尔顿建议发表其研究成果以鼓励“有天赋的人”之间通婚时,达尔文预见了实际的困难,这是“唯一可行的方案,但我担心的是乌托邦式的,改善人类进程的计划会因此产生”。他宁愿简单地宣传继承的重要性,而将决定权留给个人[193] </ref>。弗朗西斯·高尔顿在1883年将这一研究领域命名为“优生学”。达尔文去世后,他的理论被引用来促进优生政策的推行。[191]

社会进化论运动

达尔文的名气和声望使他的名字经常与思想及运动联系在一起。这些思想及运动有时与他的著作仅具有间接关系,有时甚至与他的观点直接背道而驰。

托马斯·马尔萨斯认为,上帝放任人口增长超过资源供给,是为了使人类更有生产力地工作,并抑制了家庭的组建。这在1830年代被用于证明工作场所和自由放任经济学的合理性。当时,进化论被认为具有社会意义,赫伯特·斯宾塞Herbert Spencer在其1851年的著作《社会静力学 Social Statics》中以拉马克进化论为基础,阐述了人类自由和个人自由的思想。

《物种起源》在1859年出版后不久,批评家们嘲笑达尔文对生存斗争的描述是在为当时英国工业资本主义的马尔萨斯主义辩护。后来达尔文主义一词开始用于进化思想,包括斯宾塞Spencer的“适者生存”思想和自由市场的进步,以及Ernst Haeckel的人类发展多元论。作家利用自然选择来主张各种经常相互矛盾的意识形态,例如放任自由 “狗吃狗”的资本主义,殖民主义和帝国主义。然而,达尔文的整体自然观包括了“一个人对另一个人的依赖”。因此,和平主义者,社会主义者,自由社会改革者和无政府主义者(例如Peter Kropotkin)都强调了合作对于物种内部斗争的价值。达尔文本人坚称,社会政策不应仅仅以斗争和自然选择的观念为指导。

1880年代后期,优生运动发展了生物遗传学的思想,并吸收了达尔文主义的某些观念从而为他们的思想提供了科学依据。在英国,大多数人赞同达尔文对自愿改善的谨慎态度,并试图鼓励那些具有“积极优生”思想特征的人。在“达尔文主义的消亡”期间,孟德尔遗传学为优生学提供了科学基础。在美国,加拿大和澳大利亚,反向优生学开始除去“笨拙”的一代,并使之成为生育思想的主流。美国的优生拥护者甚至颁布了强制性绝育法,随后该法案又被其他几个国家引入。不过后来,纳粹优生学使该领域声名狼藉。

“社会达尔文主义”一词在1890年代左右很少使用,但在1940年代作为贬义词而流行,由理查德·霍夫施塔特Richard Hofstadter用来抨击自由放任的保守主义派,像是威廉·格雷厄姆·萨姆纳William Graham Sumner一样反对改革和社会主义的人。从那时起,它就被那些认为进化论会导致严重的道德后果的反对者滥用。

著作

达尔文是一位著作等身的学者。即使在还没有发表有关进化的论文时,他还是《猎犬号 The Voyage of the Beagle》的作者、在南美洲发表并解决了珊瑚环礁形成难题的地质学家以及发表了有关藤壶权威著作的生物学家。虽然《物种起源 the Origin of Species》在他作品集中占了主导地位,但《人的由来 The Descent of Man》和《人类与动物的情感表达 The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals》同样产生了巨大的影响。另外他关于植物的著作有《植物运动的力量 The Power of Movement in Plants》以及他的遗作《腐植土的产生与蚯蚓的作用 》,都是业界举足轻重的创新研究成果。[194]

另见

笔记

- 达尔文是一位自然学家、地质学家、生物学家和作家。他曾担任过医生的助理和两年的医学生,也接受过成为牧师的教育;同时他还接受过动物标本制作方面的培训。

- 罗伯特·菲茨罗伊在航行之后因圣经直译主义而闻名,但此时他对莱尔的思想颇有兴趣,后来他们在莱尔要求南美航行考察前相遇。菲茨罗伊在巴塔哥尼亚Patagonia圣克鲁斯河River Santa Cruz登高期间用日记的形式记录了他的观点,即平原其实是海滩高地。但在他返航后,他与一位虔诚的教徒女士结婚,随后便放弃了这些想法。(Browne 1995,第186、414页)

- 在《物种起源》第十三章的“形态学”部分中,达尔文评论了人类与其他哺乳动物之间的同源异体骨模式,并写道:“人类用来抓东西的手,鼹鼠用来挖掘的爪子,马匹用来跑步的腿,海豚用来游泳的鳍,以及蝙蝠用来飞的翅膀,他们是否都是按照相同的模式构造而成,其实是相同的骨骼长在相同的位置?想来没有什么能比这种猜测更有趣了”。在最后一章中,达尔文还提到“男人的手,蝙蝠的翅膀,海豚的鳍和马的腿,这些骨头构造都是相同的[195] ……这显然解释了血统论,或者说是共同祖先学说。这些骨头在缓慢且连续地修正变化以适应它们的新功能。”

- 达尔文在《物种起源》中的结论中还提到了人类起源,“在遥远的将来,我看到了更为重要的研究领域,它拥有广阔的前景。心理学研究将通过获取需求不同程度的智力和能力,以分阶级为基础来深入发展。人类的起源和历史终将被照亮。”[128]

- 在“第六章:理论上的困难”中,他提到了性选择:“出于同一目的,我可能已经引证了足够多关于人类各种族之间的差异事实,这些差异是如此的明显,以至于它们的根源可以带给我们一些启示,主要通过特定类型的性选择。但是,如果不引入大量细节,我的推理就会显得很轻率。”[127]

- 在1871年出版的《人类的由来》中,达尔文在第一段讨论道:

“多年来,我收集了很多关于人类的起源或由来的笔记,我无意对此主题进行发布,更确切地说是我决定不发表,因为我认为这仅是个人观点,是我应由此对自己的观点产生质疑,而非大众。在我《物种起源》首版中,足以表明通过这项工作,‘将对人类的起源及其历史产生新的领悟。’这意味着,在尊重人类在地球上所有的表现行为前提下,我们必须将其与任何有机物统一在一起。”在1874年第二版的序言中,达尔文增加了对第二点的阐述:“一些批评家说过,当我发现无法通过自然选择来解释人的许多结构细节时,我发明了性选择。但是,我在第一版的《物种起源》中就对这一原则给出了可以相当清晰的草图,我在那里就指出过它也适用于人类。”

- 例如,可参见夏洛特·珀金斯·吉尔曼Charlotte Perkins Gilman的WILLA第4卷,和黛博拉·德·西蒙妮Deborah M. De Simone的《教育女性化Feminization of Education》:“在由达尔文的《物种起源》引起的“智力混乱”时期,吉尔曼与一代成熟的思想家均分享了许多基本的教育思想。在相信个人可以指导人类和社会发展的信念的前提下,许多进步主义者开始将教育视为促进社会发展和解决诸如城市化、贫困或移民等问题的灵丹妙药。”

- 另一个例子,请参见吉尔伯特Gilbert和沙利文Sullivan的歌剧《公主艾达Princess Ida》的歌曲“血统高贵的淑女”,它描述了男人(而非女人!)身上的猿猴血统。

- 1826年,约翰·埃德蒙斯顿(John Edmonstone)从达尔文那里汲取了教训,他进一步证实了达尔文关于黑人与欧洲人具有基本的人性并在精神上有许多相似之处的信念[26]。在猎犬号航行的早期,达尔文因为批评费兹罗伊的争辩和其对奴隶制的称赞,差点失去了在船上的位置。(达尔文1958年,第74页)他在书中写道:“选举中人们所表现出对奴隶制的看法都如此的理所当然。如果英国是第一个完全废除它的欧洲国家,那对英国来说是一件多么骄傲的事!离开英格兰之前,他们对我说,在经历过奴隶制国家生活之后,他们相信我所有的观点都会改变;然而我知道,唯一可能的变化是对黑人特征总结出更高的评价。”(Darwin 1887,p。246)就说火地岛人,他“无法相信野蛮人和文明人之间的区别有多大:会是大于野生动物和驯养动物之间的距离,因为人类具有更大的改良能力”,但他认识并喜欢杰米·巴顿这样的火地岛人:“当我想起他的许多优良品质时,对我来说似乎很美妙,他应该属于我们同一种族,毫无疑问我们拥有同样的性格属性,而我们在这里初次见到他时却是悲惨而堕落的野蛮人。” (Darwin1845年,第205、207-208页)

- 在《人类的由来》中,达尔文在表达反对“将所谓的人类种族列为不同的物种”时,提到了火地岛人和埃德蒙斯顿的思想与欧洲人的思想非常相似。[196]

- 他拒绝虐待土著人民,例如他记录了巴塔哥尼亚男人、女人和儿童之间的屠杀,“这里的每个人都完全相信这是最公正的战争,因为它是针对野蛮人的。在这个时代,谁会相信这样的暴行竟然会在基督教文明国家发生?” (Darwin 1845, p. 102)

- 遗传学家将人类遗传学作为孟德尔遗传来研究,而优生学运动则试图管理社会,尤其是试图改变英国的社会阶层差距以及美国的残疾和种族划分等问题。但这导致了遗传学家将其视为不切实际的伪科学。后来,发生了人类自由交配到反向优生的转变,包括美国的强制性绝育法,以及后期被纳粹德国借用,围绕优劣种族主义和“种族卫生”的思想,并将其作为纳粹优生学的基础。

(Thurtle, Phillip (17 December 1996). "the creation of genetic identity". SEHR. Vol. 5, no. Supplement: Cultural and Technological Incubations of Fascism. Retrieved 11 November 2008.Edwards, A. W. F. (1 April 2000). "The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection". Genetics. Vol. 154, no. April 2000. pp. 1419–1426. PMC 1461012. PMID 10747041. Retrieved 11 November 2008.Wilkins, John. "Evolving Thoughts: Darwin and the Holocaust 3: eugenics". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.))

- David Quammen认为,“在达尔文出版了多本经过实证研究的,谨慎的进化论书后,他转向了这些神秘的植物学研究。但这却是‘极其令人生厌’的,不过至少在某种程度上,让那些为争夺猿猴,天使和灵魂而战的吵闹争论者不再继续打扰他。”

引用

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Search Results: Record – Darwin; Charles Robert". catalogues.royalsociety.org. 20 June 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ "Darwin Endless Forms » Darwin in Cambridge". Archived from the original on 23 March 2017.

- ↑ "Charles Darwin's personal finances revealed in new find". 22 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:3的引用提供文字 - ↑ Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. Viking. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-0-670-02053-9. https://archive.org/details/whyevolutionistr00coyn/page/8.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为Larson79-111的引用提供文字 - ↑ "Special feature: Darwin 200". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Westminster Abbey » Charles Darwin". Westminster Abbey » Home. 2 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

Leff 2000, Darwin's Burial - ↑ Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-923084-6. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780199230846/page/17.

- ↑ Glass, Bentley (1959). Forerunners of Darwin. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. iv. ISBN 978-0-8018-0222-5.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为JvW的引用提供文字 - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为b3847的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:8的引用提供文字 - ↑ Carroll, Joseph, ed. (2003). On the origin of species by means of natural selection. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-55111-337-1.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为whowas的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:10的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:11的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:12的引用提供文字 - ↑ Beddall, B. G. (1968). "Wallace, Darwin, and the Theory of Natural Selection". Journal of the History of Biology. 1 (2): 261–323. doi:10.1007/BF00351923.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:14的引用提供文字 - ↑ "AboutDarwin.com – All of Darwin's Books". www.aboutdarwin.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ↑ Desmond, Adrian J. (13 September 2002). "Charles Darwin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ↑ John H. Wahlert (11 June 2001). "The Mount House, Shrewsbury, England (Charles Darwin)". Darwin and Darwinism. Baruch College. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ↑ Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. 339–40. https://archive.org/details/manhisgods00smit.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为skool的引用提供文字 - ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为eddy的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:19的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:20的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:21的引用提供文字 - ↑ 30.0 30.1 Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. 357–58. https://archive.org/details/manhisgods00smit.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Darwin, Charles (1901). The life and letters of Charles Darwin. vol. 1. D. Appleton. pp. 43–44. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hw2nmd;view=1up;seq=61.

- ↑ Van Wyhe, John (ed.). "Darwin's insects in Stephens' Illustrations of British entomology (1829-32)". Darwin Online. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为dar57的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:23的引用提供文字 - ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为syd5-7的引用提供文字 - ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为db的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:24的引用提供文字 - ↑ "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 105 – Henslow, J. S. to Darwin, C. R., 24 Aug 1831". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:26的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为Browne的引用提供文字 - ↑ 41.0 41.1 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为kix的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:27的引用提供文字 - ↑ Gordon Chancellor; Randal Keynes (October 2006). "Darwin's field notes on the Galapagos: 'A little world within itself'". Darwin Online. Archived from the original on 1 September 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为plankton的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:28的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:29的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:30的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:31的引用提供文字 - ↑ 49.0 49.1 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为k206的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:32的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:33的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:34的引用提供文字 - ↑ "Darwin Online: 'Hurrah Chiloe': an introduction to the Port Desire Notebook". Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:35的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:36的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:37的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:38的引用提供文字 - ↑ 58.0 58.1 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为atolls的引用提供文字 - ↑ 59.0 59.1 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为k356的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:39的引用提供文字 - ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Darwin Online: Coccatoos & Crows: An introduction to the Sydney Notebook". Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:40的引用提供文字 - ↑ "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 301 – Darwin, C.R. to Darwin, C.S., 29 Apr 1836". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:41的引用提供文字 - ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为Rascals的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为xix的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:42的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:43的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:44的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:45的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:46的引用提供文字 - ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为:47的引用提供文字 - ↑ 73.0 73.1 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 346 – Darwin, C. R. to Darwin, C. S., 27 Feb 1837". Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2008. proposes a move on Friday 3 March 1837,

Darwin's Journal (Darwin 2006, pp. 12 verso) backdated from August 1838 gives a date of 6 March 1837 - ↑ 74.0 74.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 201, 212–221

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Sulloway 1982, pp. 9, 20–23

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Browne 1995, p. 360

"Darwin, C. R. (Read 14 March 1837) Notes on Rhea americana and Rhea darwinii, Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London". Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008. - ↑ 77.0 77.1 Herbert 1980, pp. 7–10

van Wyhe 2008b, p. 44

Darwin 1837, pp. 1–13, 26, 36, 74

Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 229–232 - ↑ 78.0 78.1 https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-55044129

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Browne 1995, pp. 367–369

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Keynes 2001, p. xix

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 233–234

"Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 404 – Buckland, William to Geological Society of London, 9 Mar 1838". Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2008. - ↑ 82.0 82.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 233–236.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 241–244, 426

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Browne 1995, p. xii

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 241–244

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 252, 476, 531

Darwin 1958, p. 115 - ↑ 87.0 87.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 254

Browne 1995, pp. 377–378

Darwin 1958, p. 84 - ↑ 88.0 88.1 Darwin 1958, pp. 232–233

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 256–259

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 "Darwin transmutation notebook D pp. 134e–135e". Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 264–265

Browne 1995, pp. 385–388

Darwin 1842, p. 7 - ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 92.3 Darwin 1958, p. 120

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Darwin transmutation notebook E p. 75". Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "Darwin transmutation notebook E p. 71". Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 95.3 95.4 95.5 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Belief: historical essay". Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 272–279

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 279

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 419 – Darwin, C. R. to Fox, W. D., (15 June 1838)". Archived from the original on 4 September 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 van Wyhe 2007, pp. 186–192

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Darwin 1887, p. 32.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 292

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 292–293

Darwin 1842, pp. xvi–xvii - ↑ 103.0 103.1 Darwin 1958, p. 114

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 van Wyhe 2007, pp. 183–184

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 729 – Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., (11 January 1844)". Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 734 – Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., 29 January 1844". Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 van Wyhe 2007, p. 188

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Browne 1995, pp. 461–465

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 814 – Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., (7 Jan 1845)". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 van Wyhe 2007, pp. 190–191

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 320–323, 339–348

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 1236 – Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 28 Mar 1849". Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Browne 1995, pp. 498–501

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Darwin 1958, pp. 117–118

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 383–387

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 Freeman 2007, pp. 107, 109

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 419–420

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 412–441, 457–458, 462–463

Desmond & Moore 2009, pp. 283–284, 290–292, 295 - ↑ 119.0 119.1 Ball, P. (2011). Shipping timetables debunk Darwin plagiarism accusations: Evidence challenges claims that Charles Darwin stole ideas from Alfred Russel Wallace. Nature. online -{zh-cn:互联网档案馆; zh-tw:網際網路檔案館; zh-hk:互聯網檔案館;}-的存檔,存档日期22 February 2012.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Van Wyhe, John; Rookmaaker, Kees (2012). "A new theory to explain the receipt of Wallace's Ternate Essay by Darwin in 1858". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 105: 249–252. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01808.x.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 466–470

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 Browne 2002, pp. 40–42, 48–49

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Darwin 1958, p. 122

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 374–474

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 477

- ↑ Darwin 1859, p. 459

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 127.2 Darwin 1859, p. 199

Darwin & Costa 2009, p. 199

Desmond & Moore 2009, p. 310 - ↑ 128.0 128.1 128.2 128.3 128.4 Darwin 1859, p. 488

Darwin & Costa 2009, pp. 199, 488

van Wyhe 2008 - ↑ 129.0 129.1 Darwin 1859, p. 5

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 Darwin 1859, p. 492

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 Browne 2002, p. 59, Freeman 1977, pp. 79–80

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 van Wyhe 2008b, p. 48

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 Browne 2002, pp. 103–104, 379

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 Radick 2013, pp. 174–175

Huxley & Kettlewell 1965, p. 88 - ↑ 135.0 135.1 Browne 2002, p. 87

Leifchild 1859 - ↑ 136.0 136.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 477–491

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 Browne 2002, pp. 110–112

- ↑ 138.0 138.1 Bowler 2003, pp. 158, 186

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 139.2 139.3 139.4 139.5 139.6 "Darwin and design: historical essay". Darwin Correspondence Project. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 487–488, 500

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 141.2 Miles 2001

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 Bowler 2003, p. 185

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 Browne 2002, pp. 156–159

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 144.2 144.3 Browne 2002, pp. 217–226

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 4652 – Falconer, Hugh to Darwin, C. R., 3 Nov (1864)". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 4807 – Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., (7–8 Apr 1865)". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 Bowler 2003, p. 196

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 507–508

Browne 2002, pp. 128–129, 138 - ↑ 149.0 149.1 Browne 2002, pp. 373–379

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 van Wyhe 2008b, pp. 50–55

- ↑ 151.0 151.1 "The correspondence of Charles Darwin, volume 14: 1866". Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2009. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 25 June 2012

- ↑ 152.0 152.1 Smith 1999.

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 Freeman 1977, p. 122

- ↑ 154.0 154.1 Darwin 1871, pp. 385–405

Browne 2002, pp. 339–343 - ↑ 155.0 155.1 Browne 2002, pp. 359–369

Darwin 1887, p. 133 - ↑ 156.0 156.1 Darwin 1871, p. 405

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 Darwin's Women -{zh-cn:互联网档案馆; zh-tw:網際網路檔案館; zh-hk:互聯網檔案館;}-的存檔,存档日期12 February 2020. at Cambridge University

- ↑ Colp, Ralph (2008). "The Final 模板:Sic". Darwin's Illness. pp. 116–120. doi:10.5744/florida/9780813032313.003.0014. ISBN 978-0-8130-3231-3.

- ↑ 159.0 159.1 159.2 Clayton, Julie (24 June 2010). "Chagas disease 101". Nature (in English). 465 (n7301_supp): S4–S5. Bibcode:2010Natur.465S...3C. doi:10.1038/nature09220. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20571553. S2CID 205221512.

- ↑ 160.0 160.1 "The Case of Charles Darwin". dna.kdna.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.