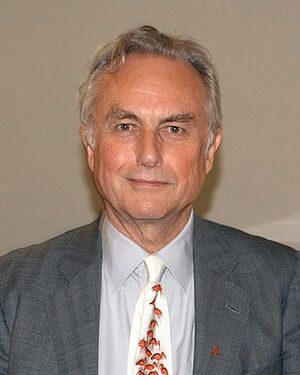

理查德·道金斯

基本信息

| 类别 | 信息 |

|---|---|

| 姓名 | 理查德·道金斯 |

| 出生名 | 克林顿·理查德·道金斯 |

| 出生日 | 1941年3月26日 |

| 出生地 | 肯尼亚 内罗毕 |

| 国籍 | 英国 |

| 教育背景 | 英格兰 昂德尔公立学校(Oundle School) 牛津大学 (MA, DPhil) |

| 博士生导师 | 尼古拉斯·廷贝亨(Nikolaas Tinbergen) |

| 博士生 | Alan Grafen |

| 博士论文题目 | Selective pecking in the domestic chick(1967) |

| 工作地点 | 伯克利加州大学 牛津大学新学院(New College) |

| 主要工作 |

|

| 学生 | Mark Ridley |

| 受启发于 | Charles Darwin, W. D. Hamilton, Nikolaas Tinbergen |

| 影响者 | Andrew F. Read, Helena Cronin, John Krebs, Baron Krebs, David Haig, Daniel Dennett, David Deutsch, Steven Pinker, Martin Daly, Margo Wilson, Randolph M. Nesse, Kim Sterelny, Michael Shermer, Richard Harries, Baron Harries of Pentregarth, A. C. Grayling, Marek Kohn, David P. Barash, Matt Ridley, Philip Pullman |

| 配偶 | Marian Stamp(1967-1984) Eve Barham(1984-19??) Lalla Ward(1992-2016) |

| 子女 | 1 |

| 荣誉 | ZSL Silver Medal (1989) Michael Faraday Prize (1990) International Cosmos Prize (1997) Nierenberg Prize (2009) FRS (2001) |

| 签名 |

理查德 · 道金斯 Richard Dawkins(生于1941年3月26日)是英国进化生物学家和作家。他是牛津大学新学院的荣誉退休研究员,并于1995年至2008年在牛津大学担任公众理解科学教授。作为一个无神论者,他以对神创论和智慧设计论的批判而闻名。[2]

道金斯最早在1976年出版的《自私的基因》一书中崭露头角,该书推广了以基因为中心的进化论观点,并引入了“模因”(meme)一词。在1982年出版的《扩展的表现性 Extended Phenotype》(译注:未找到对应中文翻译作品)一书中,他将一个有影响力的概念引入进化生物学,即基因的表现型效应不一定局限于有机体,而是可以延伸到环境中。2006年,他创立了理查德·道金斯理性与科学基金会。

在《盲眼钟表匠(1986)》中,道金斯反驳了基于生命有机体的复杂性而支持存在超自然创造者的观点。相反,他将进化过程描述为类似于一个盲人钟表匠,因为繁殖、突变和选择是不受任何设计师指导的。在2006年出版的《上帝错觉》道金斯认为超自然的创造者几乎肯定不存在,而宗教信仰只是一种错觉。道金斯的无神论立场有时会引起争议。[3][4][5]

道金斯在学术和写作领域获得许多奖项。他常在电视、广播和互联网上露面,主要讨论他的书籍、无神论以及他作为公共知识分子的想法和观点。[6]

背景

早期生活

1941年3月26日,克林顿·理查德·道金斯出生于当时的英属肯尼亚首都内罗毕[7]。道金斯后来通过契约投票把克林顿从他的名字中去掉了。他是让·玛丽·维维安 Jean Mary Vyvyan(1916-2019年)[8][9]和克林顿·约翰·道金斯 Clinton John Dawkins(1915-2010年)的儿子,后者是尼亚萨兰(今天的马拉维)英国殖民局的一名农业公务员,出身于牛津郡一个有土地的贵族家庭。[7][10][11]他的父亲在第二次世界大战期间被召入国王的非洲步枪队[12][13],并于1949年返回英国,当时道金斯只有八岁。他的父亲继承了位于牛津郡诺顿公园的一处乡村庄园,并进行了商业开发。[11]道金斯住在英国的牛津[14]。他有一个妹妹,叫莎拉。[15]

他的父母对自然科学很感兴趣,他们用科学的术语回答了道金斯的问题。[16]道金斯将他的童年描述为“一个正常的英国国教徒的成长过程”。[17]他信奉基督教直到青少年时期的一半,那时他得出结论,进化论本身是对生命复杂性更好的解释,并且不再相信上帝。[15]道金斯说: “我(当时还)信仰宗教的主要原因是我对生活的复杂性印象深刻,感觉它必须有一个设计师才能出现如此复杂之物。我认为当我意识到达尔文主义是一个更加优越的解释时,我就被拉出了设计论观点。这让我再无信仰宗教的理由。”[15]

教育背景

1949年,8岁的道金斯从尼亚萨兰回到英格兰,加入了威尔特郡的查芬格罗夫学校[18],之后从1954年到1959年,他进入了北安普敦郡的奥德尔学校 Oundle School,一所有着英格兰教会精神的英国公立学校[15][19]。在昂德尔的时候,道金斯第一次读了伯特兰·罗素的《为什么我不是基督徒》。他于1962年毕业于牛津大学贝利尔学院,学习动物学。在那里,他得到了诺贝尔奖获得者动物行为学家尼古拉斯·廷贝亨的指导,以二等荣誉毕业。[20]

在廷贝亨的指导下,他继续作为一名研究生,在1966年获得了哲学硕士和博士学位[21],又做了一年的研究助理[22][23]。廷伯根是动物行为研究的先驱,特别是在本能、学习和选择领域[24]。道金斯在这一时期的研究涉及动物决策模型[25]。

教学生涯

从1967年到1969年,道金斯是加州大学伯克利分校的动物学助理教授。在此期间,加州大学伯克利分校的学生和教师大多反对正在进行的越南战争,道金斯参与了反战示威和活动[26]。1970年,他回到牛津大学担任讲师。1990年,他成为动物学副教授。1995年,他被任命为牛津大学的西蒙尼讲席教授(公众科学普及教授),这个职位是查尔斯·西蒙尼授予的,持有者“应该对公众对某个科学领域的理解做出重要贡献”[27]。该席位第一个持有者是理查德·道金斯.[28] 。从1995年到2008年,他一直担任该教授席位。[29]

自1970年以来,他一直是牛津大学新学院 New College,University of Oxford的研究员,现在是名誉研究员[30][31]。他曾发表多次演讲,包括亨利·西奇威克纪念讲座(1989年)、第一次伊拉斯谟斯·达尔文纪念讲座(1990年)、迈克尔·法拉第讲座(1991年)、 T·H·赫胥黎纪念讲座(1992年)、欧文纪念讲座(1997年)、廷贝亨讲座(2004年)及坦纳讲座(2003年)[22]。1991年,他在皇家学会圣诞讲座发表了《在宇宙中成长的孩子》一书。他还编辑了几本期刊,并担任了 Encarta 百科全书和进化百科全书的编辑顾问。他是世俗人文主义自由调查杂志委员会的高级编辑和专栏作家,自《怀疑论》杂志成立以来,他一直是该杂志编辑委员会的成员。[32]

道金斯曾经担任过各种奖项的评委,包括皇家学会的法拉第奖和英国电视学院奖,同时也是英国科学协会生物科学部门的主席[22]。2004年,牛津大学贝利奥尔学院设立了道金斯奖,以表彰“对动物生态和行为的杰出研究,这些动物的福祉和生存可能受到人类活动的威胁”[33]。2008年9月,他从教授职位上退休,宣布计划“写一本针对年轻人的书,在书中他将警告他们不要相信‘反科学’的童话。”[34]

2011年,道金斯加入了新人文学院的教授职位。这是一所位于伦敦的私立大学,由A·C·格雷林创办,于2012年9月开办。[35]

工作

演化生物学

道金斯最著名的是他将基因作为进化中选择的主要单位而广为人知[36][37],这一观点在他的著作《自私的基因 The Selfish Gene》(1976)中得到了最清晰的阐述。他在书中指出,“所有生命都是通过复制实体的不同生存方式进化的”。在《扩展的表现型 Extended Phenotype》(1982) 中他将自然选择描述为“复制因子相互超越繁殖的过程”。此外他还向更广泛的受众介绍了他在1977年提出的有影响力的概念[38],即基因的表现型效应不一定局限于有机体,而是可以延伸到环境中,包括其他有机体的表现型效应。道金斯认为扩展表型是他对进化生物学最重要的贡献,他认为生态位构建是扩展表型的一个特例。扩展表型的概念有助于解释进化,但它无助于预测特定的结果。[39]

道金斯一直对进化过程中的非适应性过程(如古尔德和路翁丁所描述的Spandrels)以及“高于”基因水平的选择持怀疑态度[40]。他特别怀疑群体选择作为理解利他主义的基础的实际可能性或重要性。这种行为起初似乎是一种进化悖论,因为帮助他人会耗费宝贵的资源,并降低自己的适应能力。以前,许多人把这解释为群体选择的一个方面:个体做的是对种群或整个物种的生存最有利的事情。英国进化生物学家W.D.汉密尔顿在他的整体适应度理论中使用基因频率分析来说明,如果这种利他主义的行为者和接受者(包括近亲)之间有足够的遗传相似性,那么遗传的利他主义特征是如何进化的[41]。汉密尔顿的整体适应度已经成功地应用于包括人类在内的广泛的生物体中。类似地,罗伯特·泰弗士从以基因为中心的模型的角度思考,发展了互利主义理论,即一个有机体在对未来互换的预期中为另一个有机体提供利益[42]。道金斯在《自私的基因》中推广了这些观点,并在自己的作品中加以发展[43]。2012年6月,道金斯对生物学家 E.O.威尔逊2012年出版的《地球的社会征服》一书提出严厉批评,认为该书误解了汉密尔顿的亲缘选择理论[44][45]。道金斯还强烈批评独立科学家詹姆斯·洛夫洛克的盖亚假说。[46][47][48]

道金斯的生物学方法的批评者认为,把基因作为选择的单位(一个个体要么成功要么失败的单一事件)是具有误导性的。他们说,这种基因可以更好地描述为一个进化单位(一个种群中等位基因频率的长期变化)[49] 。在《自私的基因》一书中,道金斯解释说他使用的是乔治·C ·威廉斯对基因的定义,即“以可观的频率分离和重组”[50]。另一个常见的反对意见是,一个基因不能单独存活,而必须与其他基因合作来建立一个个体,因此一个基因不可能是一个独立的“单元”[51] 。在《扩展的表现型》一书中,道金斯提出,从单个基因的观点来看,所有其他基因都是它所适应的环境的一部分。

支持更高水平选择的人(如理查德·莱翁廷、大卫·斯隆·威尔逊和艾略特·索伯)认为,有许多现象(包括利他主义)是基因层面的选择无法令人满意地解释的。哲学家玛丽•米吉利(Mary Midgley)曾批评道金斯的基因选择、模因论和社会生物学过于简化[52][53] 。她指出,道金斯作品之所以受欢迎,是因为时代精神中的因素,比如撒切尔/里根时代日益增强的个人主义[54][55]。

在一系列关于进化机制和解释的争论中[56][57],一个派别经常以道金斯的名字命名,而另一个派别则以美国古生物学家史蒂芬·古尔德的名字命名[58][59]。同样值得一提的是,道金斯和古尔德在社会生物学和进化心理学的争论中是杰出的评论家,道金斯通常时赞同和欣赏,而古尔德普遍持批判态度[60]

。道金斯立场的一个典型例子是他对史蒂文·罗斯、里昂·J·卡明和理查·C·莱翁廷的《不在我们的基因里 Not In

Our Gene》的严厉评论[61]。在这个问题上,另外两位经常被认为与道金斯意见一致的思想家是史蒂文•平克 Steven Pinker和丹尼尔•丹尼特 Daniel Dennett。丹尼特提倡以基因为中心的进化论观点,并为生物学中的还原论辩护[62] 。道金斯和古尔德尽管在学术上存在分歧,但他们之间并没有敌对的个人关系,道金斯在他2003年出版的《一个魔鬼的牧师 A Devil's Chaplain》一书中,将很大一部分献给了去年去世的古尔德。

当被问及达尔文主义是否影响了他对生活的日常理解时,道金斯说:“在某种程度上是这样的。我的眼睛一直睁得大大的,看着存在的非凡事实。不仅仅是人类的存在,还有生命的存在,以及这个惊人的强大过程——自然选择——是如何将物理学和化学的简单事实应用到红杉树和人类身上的。那种惊奇的感觉从未离开过我的脑海。另一方面,我当然不允许达尔文主义影响我对人类社会生活的感受,”这意味着他认为个体人类可以选择退出达尔文主义的生存机器,因为他们被自我意识解放了。[14]

提出“模因”概念

道金斯在《自私的基因》一书中创造了“模因”(meme)这个词(相当于行为学上基因) ,以此鼓励读者思考达尔文的原则如何能够超越基因的范畴。这本来是他的“复制因子”论点的延伸,但是在其他作家的手中,如丹尼尔•丹尼特 Daniel Dennett和苏珊•布莱克莫尔 Susan Blackmore,这个概念呈现出了自己的生命力。这些作家的推广后来引发了模因论的出现,而道金斯已经远离了这个领域。[63]

道金斯的模因指的是任何文化实体,一个观察者可能会考虑一个复制者的某个想法或一套想法。他推测,人们可能认为许多文化实体有能力进行这种复制,通常是通过与人类的交流和接触,人类已经进化成了高效(尽管并不完美)的信息和行为复制者。因为模因并不总是完美的复制,它们可能会演化、结合、或者被其他观点修改,这就导致了新的模因,它们自身可能会证明是比它们的前辈更有效/低效的复制因子,从而为基于模因的文化进化假设提供了一个框架,这个概念类似于基于基因的生物进化理论[64]。

虽然道金斯发明了模因这个词,但他并没有宣称这个想法是完全新颖的[65],过去也有其他类似的表达方式。例如,约翰•洛朗 John Laurent表示,这个术语可能源自鲜为人知的德国生物学家理查德•塞蒙 Richard Semon的研究[66]。塞蒙认为“mneme”是遗传的神经记忆痕迹(有意识或潜意识)的集合,尽管这种观点被现代生物学家认为是拉马克主义的[67]。洛朗还发现了“mneme” 这个词在莫里斯·梅特林克的《白蚁的生活》(1926)中的使用,梅特林克自己也表示,他是从塞蒙的作品中得到这个短语的[66] 。在他自己的工作中,梅特林克试图解释白蚁和蚂蚁的记忆,声称神经记忆痕迹是“在个人记忆中”添加的。尽管如此,詹姆斯•格雷克 James Gleick将道金斯的“文化基因 meme”概念描述为“他最著名的创造,远比他自私的基因或后来反对宗教狂热的说教更具影响力”[68]。

设立基金

2006年,道金斯成立了“理查德·道金斯理性与科学基金会”.[69]。一个非营利组织基金会,为信仰和宗教心理学的研究提供资金,资助科学教育项目和材料,宣传和支持世俗性的慈善组织。2016年1月,基金会宣布与调查中心合并,道金斯成为新组织的董事会成员[70]。

对宗教的批评

道金斯在13岁时加入英国国教,但他开始对这些信仰产生怀疑。他说,他对科学和进化过程的理解使他质疑,在文明世界中担任领导职务的成年人怎么还没有受过生物学方面的教育[71],他还对在科学领域精通的人中怎么还能保持对上帝的信仰感到困惑。道金斯指出,一些物理学家用“上帝”来比喻宇宙中普遍存在的令人敬畏的神秘事物,这在人们中间造成了困惑和误解,他们错误地认为自己在谈论一个神秘的存在,这个存在可以宽恕罪恶,改变葡萄酒的质量,或者让人们在死后继续活着[72]。他不同意史蒂芬·古尔德的不重叠的原则[73],并建议上帝的存在应该被视为一个科学假说,像任何其他假说一样。道金斯成为了一个著名的宗教批评家,并表示他对宗教的反对是双重的: 宗教既是冲突的来源,也是无证据信仰的正当理由。他认为信仰——没有事实依据的信仰——是“世界上最大的罪恶之一”[74]。

在道金斯的“神存在”陈述的怀疑光谱中,有7个等级介于1(100% 确定上帝或神存在)和7(100% 确定上帝或神不存在)。Dawkins 说他是6.9,这代表了一个“事实上的无神论者”,他认为“我不能确定,但我认为上帝是非常不可能的,我的生活在他不存在的假设之上。”当被问及他的轻微的不确定性时,道金斯戏谑地说: “我是不可知论者,以至于我甚至不能确认或否认花园尽头的仙女 fairies at the bottom of the garden。”[75][76] 2014年5月,在威尔士的海伊节上,道金斯解释说,虽然他不相信基督教信仰的超自然元素,但他仍然怀念宗教仪式的一面[77]。除了对神的信仰之外,Dawkins 还批评宗教信仰是非理性的,比如耶稣把水变成了酒,胚胎开始时只是一小块,神奇的内衣会保护你,耶稣复活了,精液来自脊椎,耶稣在水上行走,太阳落在沼泽里,伊甸园(2008年电影)存在于 Adam-ondi-Ahman,耶稣的母亲是一个处女,穆罕默德分裂了月亮,还有拉撒路从死亡中复活。

自从2006年他最畅销的书《上帝错觉》出版以来,道金斯在有关科学和宗教的公共辩论中声名鹊起,这本书成为了国际畅销书[78] 。截至2015年,该书已售出300多万册,并被翻译成30多种语言。它的成功已被许多人视为当代文化时代精神变化的标志,也被认为是新无神论的兴起[79]。道金斯在书中主张,几乎可以肯定,超自然的创造者是不存在的,宗教信仰是一种错觉——“一种固定的错误信仰”。在2002年2月的 TED 演讲中,道金斯呼吁所有无神论者公开表明自己的立场,抵制教会对政治和科学的入侵[80]。2007年9月30日,道金斯、克里斯托弗·希钦斯、山姆·哈里斯、和丹尼尔·丹尼特在希钦斯的住所进行了长达两个小时的私人的,不加修饰的讨论。这次活动被拍摄下来并命名为《无神论四骑士》[81]。

道金斯认为教育和提高意识是反对他所认为的宗教教条和灌输的主要工具[26][82][83]。这些工具包括反对某些刻板印象的斗争,他采用了光明这个词作为一种方式,将积极的公众内涵与那些拥有自然主义世界观的人联系起来。他支持建立一所自由思考的学校的想法[84],这所学校不会“向孩子们灌输思想”,而是教导孩子们寻求证据,保持怀疑、批判和开放的心态。道金斯说,这样的学校应该“教授宗教比较,正确地教授它,不偏向于特定的宗教,包括历史上重要但已经消亡的宗教,如古希腊和挪威神,如果仅仅因为这些,如亚伯拉罕经文,对于理解英国文学和欧洲历史是重要的[85][86]。道金斯同样认为,“天主教儿童”和“穆斯林儿童”等短语在社会上应被认为是荒谬的,就像“马克思主义儿童”一样,因为他认为,儿童不应根据其父母的意识形态或宗教信仰来分类[83]。

当一些批评家,如作家克里斯托弗·希钦斯,心理学家史蒂芬·平克和诺贝尔奖获得者哈罗德·克罗托,詹姆斯·D·沃森和 史蒂芬·温伯格为道金斯在宗教上的立场辩护并赞扬他的工作时[87],其他人,包括诺贝尔奖获得者理论物理学家彼得·希格斯,天体物理学家马丁·里斯,科学哲学家迈克尔·鲁斯,文学批评家特里·伊格尔顿、哲学家罗杰·斯克鲁顿、学术界和社会批评家卡米尔·帕格利亚、无神论哲学家丹尼尔·科尔姆和神学家阿利斯特·麦格拉斯都从各个方面批评道金斯,包括断言他的作品只是作为宗教原教旨主义的无神论对应物,而不是对它的富有成效的批判,他从根本上误解了他声称反驳的神学立场的基础,特别是里斯和希格斯,他们都反对道金斯对宗教的对抗姿态,认为这种姿态狭隘而“令人尴尬”,希格斯甚至将道金斯与他所批评的宗教原教旨主义者等同起来[88][89][90][91] 。无神论哲学家约翰·格雷 John Gray谴责道金斯是“反宗教的传教士”,他的主张“从任何意义上讲都不是新颖的或原创的”,他暗示道金斯“对自己思想的运作惊叹不已,错过了许多对人类至关重要的东西。”[92]格雷还批评道金斯对达尔文的忠诚。他说,如果“对达尔文来说,科学是一种探究的方法,使他能够试探性和谦逊地走向真理,对道金斯来说,科学是一种不容置疑的世界观。”作为对他的批评的回应,道金斯坚持认为神学家在解决深奥的宇宙学问题上并不比科学家好,他不是一个原教旨主义者,因为他愿意在新的证据面前改变自己的想法。[93][94]

道金斯的一些关于伊斯兰教的公开言论遭到了强烈反对。2013年,道金斯在推特上写道:“世界上所有的穆斯林获得的诺贝尔奖比剑桥大学三一学院都少,尽管他们在中世纪做了很多伟大的事情。”[95]。2016年,道金斯邀请他在东北科学与怀疑论大会 Northeast Conference on Science and suspicious上发表演讲,但因为他分享了一段“极具攻击性”的视频,嘲笑女权主义者和伊斯兰主义者”而被撤回[96]。

对神创论的批评

道金斯是神创论的杰出批评家。神创论是一种宗教信仰,认为人类、生命和宇宙都是由神创造的,不依赖于进化[97][98]。他将年轻的地球创造论者 Young Earth creationist认为地球只有几千岁的观点描述为“一个荒谬的、意识萎缩的谬误”[99]。他在1986年出版的《盲眼钟表匠》持续批判了设计论——一个重要的神创论论点。在书中,道金斯反驳了18世纪英国神学家 William Paley 所著《自然神学》中的钟表匠比喻。道金斯同意科学家们普遍持有的观点,即自然选择足以解释生物世界表面的功能性和非随机的复杂性,可以说自然选择在自然界中扮演着钟表匠的角色,尽管是自动的,不受任何设计师、非智能的盲人钟表匠的指导[100]。

1986年,道金斯和生物学家约翰·梅纳德·史密斯参加了牛津大学联盟对抗“年轻的地球”创造论者 A·E·Wilder-Smith 和圣经创造学会主席 Edgar Andrews 的辩论。然而,总的来说,道金斯听从了他已故同事史蒂芬·古尔德的建议,拒绝参加与神创论者的正式辩论,因为“他们寻求的是体面的氧气”,这样做将“仅仅通过与他们接触的行为就能给他们这种氧气”。他认为神创论者“不介意在争论中被击败。通过与我们在公共场合争论来就能给他们带来认可。”2004年12月,道金斯在接受美国记者比尔·莫耶斯 Bill Moyers的采访时说,“在科学确实知道的事情中,进化论和我们知道的任何事情一样确定。”当莫耶斯就“理论”这个词的用法向他提出质疑时,道金斯说: “进化论已经被观察到了。它只是在发生的时候没有被观察到而已。”他补充说: “这很像一个侦探在犯罪现场之后调查谋杀案... ... 当然,这个侦探实际上并没有亲眼看到谋杀发生。但是你所看到的是一个巨大的线索...大量的间接证据。这就像是用英语拼写出来的一样。”[101]

道金斯反对将智能设计论纳入科学教育,称其“根本不是一个科学论点,而是一个宗教论点”[102]。他被媒体称为“达尔文的罗特韦尔犬”[103][104] 。这里是把道金斯对标英国生物学家T·H·赫胥黎,他因拥护查尔斯·达尔文的进化论而被称为“达尔文的斗牛犬”。他一直强烈批评英国组织“科学真理 Truth in Science”,该组织在公立学校推广神创论教学。道金斯称他们的工作为“教育丑闻”。他计划通过理查德·道金斯理性与科学基金会资助学校,提供书籍、DVD和小册子,抵消他们的工作[105]。

政治观点

道金斯是一个直言不讳的无神论者[106],支持各种无神论,世俗和人文组织,包括英国人文主义者和布莱特运动[22][107][108][109][110][111][112][80]。道金斯说到无神论者应该感到骄傲,而不是抱歉,强调无神论是健康、独立思考的证据。他希望越多的无神论者认同他们自己,越多的公众会意识到有多少人是无神论者,从而减少无神论在大多数宗教中的负面影响[113]。受到同性恋权利运动的启发,他支持“走出去运动”,鼓励全世界的无神论者公开表明他们的立场。他在2008年支持了英国一项无神论者广告倡议——无神论者巴士运动,该运动旨在筹集资金,在伦敦地区的巴士上张贴无神论者广告[114]。

道金斯对人口增长和人口过剩问题的表示关切[115]。在《自私的基因》一书中,他简要地提到了人口增长,并以拉丁美洲为例,那里的人口,在该书写作的时候,每40年翻一番。他批评罗马天主教对计划生育和人口控制的态度,指出禁止避孕和“表示偏爱‘自然’的人口限制方法”的领导人最终会得到饥荒的结果。

作为大猿项目 the Great Ape Project的支持者-——这是一项将某些道德和法律权利扩展到所有大猿的运动——道金斯为 Paola Cavalieri 和 Peter Singer 编辑的大猿计划图书撰写了文章《思想的空白》。在本文中,他批评当代社会的道德态度是以“不连续的,特殊的命令”为基础[116]。

道金斯还经常在报纸和博客上评论当代政治问题,并且经常为网络科学和文化文摘《每日3夸克 3 Quarks Daily》报撰稿[117]。他的观点包括反对2003年入侵伊拉克[118]、英国的核威慑力量、时任美国总统乔治·W·布什 George W. Bush的行动[119],以及设计婴儿的伦理道德[120]。一本关于科学、宗教和政治著作的选集《一个魔鬼的牧师》收录了几篇这样的文章。他也是共和国运动的支持者,该运动旨在用民主选举产生的总统取代英国君主制度[121]。道金斯将自己描述为上世纪70年代的工党选民[122]。自民党成立以来,他一直是自民党的支持者。2009年,他在党的会议上发表讲话,反对亵渎法、替代医学和宗教学校。在2010年的英国大选中,道金斯正式支持自由民主党 Liberal Democrats,以支持他们的选举改革运动,以及他们“拒绝迎合‘信仰’”[123]。在2017年大选的准备阶段,道金斯再次支持自由民主党,并敦促选民加入该党。

2021年4月,道金斯在推特上说: “一些男人选择认同自己是女人,一些女人选择认同自己是男人。如果你否认他们真的是他们所认同的那样,你就会被诋毁。讨论一下。”在因为这条推文而受到批评后,道金斯回应说: “我无意贬低变性人。我看到我的学术“讨论”问题已被误解,我得谴责这一点。我也不打算以任何方式与美国的偏执共和党人结盟,他们现在正在利用这个问题。”[124]

道金斯表示,他支持建立联合国议会大会运动,这是一个在联合国推动民主改革的组织,并支持建立一个更负责任的国际政治制度[125]。

道金斯被认为是女权主义者[126]。他说,女权主义是“极其重要的”,是“一个值得支持的政治运动”[127]。

对后现代主义的观点

1998年,道金斯对两本与索卡尔事件有关的书表示了赞赏:保罗·R·格罗斯和诺曼·莱维特的《更高的迷信:学术左派及其与科学的争论》和索卡尔和让·布里克蒙特的《知识骗局》。这些书因其在美国大学的后现代主义的批评而闻名(即在文学研究、人类学和其他文化研究系)[128] 。

道金斯回应了许多批评家的观点,认为后现代主义使用蒙昧主义的语言来掩盖其缺乏有意义的内容。作为一个例子,他引用了精神分析学家皮埃尔-菲利克斯·伽塔利 Félix Guattari的话:

“我们可以清楚地看到,依赖于作者的线性能指链接或基本书写,与这种多参照的、多维的机械催化之间,并不存在双重单一的对应。”

这可以解释为,道金斯这持有着某种智力上的学术抱负。道金斯认为,像伽塔利或拉康这样的人物说了一堆废话,但他们希望从成功的学术生涯中获得声誉和名望:

“假设你是一个知识骗子,无话可说,但有着在学术生活中取得成功的强烈野心,召集一群虔诚的弟子,让世界各地的学生在你的书页上涂上尊敬的黄色荧光笔。你会培养什么样的文学风格?可以肯定不是一种清晰的风格,因为清晰会暴露出你的内容不足。”[128]

其他领域

作为公众科学理解的教授,道金斯一直是伪科学和替代医学的批评者。他在1998年出版的《解构彩虹 Unweaving the Rainbow》一书中考虑了约翰·济慈的指责,即通过解释彩虹,艾萨克·牛顿削弱了它的美丽。道金斯则支持相反的结论。他认为,深空、亿万年的生命进化、生物学和遗传学的微观工作机制,比“神话”和“伪科学”包含更多的美和奇迹[129]。在约翰·戴蒙德去世后出版的《蛇油》一书中,道金斯写了一个前言,他断言替代医学是有害的,即使仅仅是因为它分散了病人对更成功的常规治疗的注意力,给了人们错误的希望[130]。道金斯说: “没有替代医学。只有有效的药物和无效的药物。”道金斯在2007年4频道的电视电影《理性的敌人》中总结道,英国正被“迷信思想的流行”所笼罩[131]。

通过继续与第四频道的长期合作关系,道金斯参加了一个五部分的电视系列节目《英国的天才》。与他一起的还有科学家斯蒂芬·霍金,詹姆斯·戴森,保罗·纳斯和吉姆·哈利利。该系列节目于2010年6月首次播出,重点介绍了英国历史上的重大科学成就[132]。

2014年,他作为“100倍签字人 100x Signatory”加入了全球提高认识运动小行星日[133]。

奖项及荣誉

道金斯于1989年获得牛津大学理学博士学位。他拥有哈德斯菲尔德大学、威斯敏斯特大学、杜伦大学[134]、赫尔大学、安特卫普大学、奥斯陆大学、阿伯丁大学[135] 、开放大学、布鲁塞尔自由大学和华伦西亚大学的名誉博士学位[136]。他还拥有圣安德鲁斯大学和澳大利亚国立大学的荣誉博士学位[137][22],1997年被选为皇家文学学会会员,2001年被选为皇家学会会员。他是牛津大学科学学会的赞助人之一。

1987年,Dawkins 因其著作《盲眼钟表匠》获得了皇家文学学会奖和《洛杉矶时报》文学奖。同年,他获得了最佳电视纪录片科学节目技术奖,以表彰他在 BBC 《地平线》盲眼钟表匠节目中的工作。[22]

1996年,美国人文主义者协会给他颁发了年度人道主义者奖。2021年,他们投票撤销了这一决定,称他“打着科学话语的幌子贬低边缘化群体”,包括变性人。[138][124]

其他奖项包括伦敦动物学会银质奖章(1989年)、芬利创新奖(1990年)、法拉第奖(1990年)、中山奖(1994年)、第五届国际考斯莫斯奖奖(1997年)、基斯特勒奖(2001年)、意大利共和国总统奖章(2001年),2001年及2012年「皇帝无衣」宗教自由基金会、2002年格拉斯哥皇家哲学学会200周年凯尔文奖、2006年美国科学院成就奖金牌奖[139]及2009年尼伦伯格公共利益科学奖[140] 。他被授予德斯切纳奖,该奖项以德国反牧师作家卡尔海因茨·德施纳命名[141]。1992年,美国怀疑调查委员会委员会向 Dawkins 颁发了他们的最高奖项“理性的赞美”[142]。

2004《展望 Prospect》杂志年评选的英国公共知识分子前100名,道金斯位列第一,得票数是第二名的两倍[143][144]。在2008年的后续投票中,他也被列为候选人[145]。在《展望》2013年举行的一次民意调查中,道金斯基于65个名字被评为世界最佳思想家,这些名字主要由美国和英国的专家小组选出。[146]

2005年,汉堡的阿尔弗雷德 · 托普费尔基金会授予他莎士比亚奖,以表彰他“简洁易懂的科学知识展示”。他获得了2006年刘易斯 · 托马斯科学写作奖,以及2007年银河英国图书奖年度作家奖[147]。同年,他被《时代》杂志列为2007年全球100位最有影响力的人物之一[148] ,并在2007年每日电讯报世界100位最伟大的在世天才排行榜上名列第20位[149]。

自2003年以来,国际无神论者联盟在其年度会议上颁发了一个奖项,以表彰一位杰出的无神论者,他在那一年里为提高公众对无神论的认识做出了最大的贡献[150] 。这个奖被称为理查德·道金斯奖,以表彰道金斯自己的努力。2010年2月,道金斯被任命为无宗教自由基金会的杰出成就者荣誉理事会成员[151]。

2012年,斯里兰卡的鱼类学家为了纪念道金斯,创建了道金斯作为一个新的属名(该属的成员以前是平须属的成员)[152]。

个人生活

道金斯结过三次婚,有一个女儿。1967年8月19日,道金斯与生态学家玛丽安娜 Marian Stamp在位于安斯敦的新教沃特福德郡举行了婚礼[153]。他们在1984年离婚 [154]。1984年6月1日,他在牛津与伊芙·巴勒姆(1951-1999)结婚。他们有一个女儿,朱丽叶·艾玛·道金斯(1984年出生于牛津)。后来道金斯和巴勒姆又离婚了。1992年,他与女演员拉拉·沃德[154]在伦敦肯辛顿-切尔西区结婚。道金斯是通过他们共同的朋友道格拉斯·亚当斯认识她的[155]。道金斯和沃德在2016年分手,他们后来形容这次分手是“完全友好的”[156]。

2016年2月6日,道金斯在家中遭受了轻微出血性中风[157][158]。同年晚些时候他报告说,他几乎完全康复了。[159][160]

媒体

精选发表物

- The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1976. ISBN 978-0-19-286092-7.

- The Extended Phenotype. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1982. ISBN 978-0-19-288051-2.

- The Blind Watchmaker. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. 1986. ISBN 978-0-393-31570-7.

- River Out of Eden. New York: Basic Books. 1995. ISBN 978-0-465-06990-3. Book text

- Climbing Mount Improbable. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. 1996. ISBN 978-0-393-31682-7.

- Unweaving the Rainbow. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1998. ISBN 978-0-618-05673-6.

- A Devil's Chaplain. Weidenfeld & Nicolson (United Kingdom and Commonwealth), Houghton Mifflin (United States). 2003. ISBN 978-0753817506.

- The Ancestor's Tale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2004. ISBN 978-0-618-00583-3.

- The God Delusion. Bantam Press (United Kingdom), Houghton Mifflin (United States). 2006. ISBN 978-0-618-68000-9.

- The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. Transworld (United Kingdom and Commonwealth), Free Press (United States). 2009. ISBN 978-0-593-06173-2.

- The Magic of Reality: How We Know What's Really True. Bantam Press (United Kingdom), Free Press (United States). 2011. ISBN 978-1-4391-9281-8.

- An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist. Bantam Press (United Kingdom and United States). 2013. ISBN 978-0-06-228715-1.

- Brief Candle in the Dark: My Life in Science. Bantam Press (United Kingdom and United States). 2015. ISBN 978-0062288431.

- Science in the Soul: Selected Writings of a Passionate Rationalist. Random House. 2017. ISBN 978-1-4735-4166-5.

- Outgrowing God: A Beginner's Guide. Random House. 2019. ISBN 978-1984853912.

- Books do Furnish a Life: Reading and Writing Science. Transworld. 2021. ISBN 978-1787633698.

纪录片

- 《好男人 Nice Guys Finish First》(1986)

- 《盲眼钟表匠 The Blind Watchmaker》(1987) [161]

- 《在宇宙中成长 Growing Up in The Universe》(1991)

- 《打破科学壁垒 Break The Science Barrier》(1996)

- 《无神论 The Atheism Tapes》录音带(2004)

- 《大问题 The Big Question》(2005)-《我们为什么在这里 Why Are We Here?》

- 《万恶之源 The Root of All Evil?》(2006)

- 《理性的敌人 The Enemies of Reason》(2007)

- 《查尔斯 · 达尔文的天才 The Genius of Charles Darwin》(2008)

- 《目的的目的 The Purpose of Purpose》(2009)——美国大学巡回演讲

- 《信仰学校的威胁 Faith School Menace?)(2010)

- 《美丽的心灵 Beautiful Minds》(2012)-BBC4 纪录片

- 《性、死亡与生命的意义 Sex, Death and the Meaning of Life》(2012) [162]

- 《无信仰者 The Unbelievers》(2013)

其他露面

道金斯已经在许多电视新闻节目中露面,提供他的政治观点,特别是他作为一个无神论者的观点。他经常在电台接受采访,这也是他新书巡回宣传的一部分。他与许多宗教人物辩论过。他曾多次在大学演讲,还经常与他的巡回新书合作。截至2016年,他以自己的身份出现在IMDB Internet Movie Database,拥有超过60个credits。

- 《驱逐:不允许智慧生物》(2008)-作为自己,在一部电影中以智慧设计论的主要科学反对者的身份出现,该电影声称主流科学机构压制那些相信自己在自然界中看到智慧设计论证据并批评支持达尔文进化论证据的学者

- 《神秘博士: 被盗的地球》(2008)-作为自己

- 《辛普森一家》-《黑眼睛,请》(2013)-出现在奈德·弗兰德斯的地狱之梦中,配音为恶魔版本的自己

- 《蝴蝶、斑马与胚胎:探索演化发生学之美》(2015)-由芬兰交响金属乐队 Nightwish 担任专辑嘉宾明星。他提供了两个轨道的旁白: “战栗之前的美丽”,其中他开始了他自己的一个引用专辑,“地球上最伟大的表演”,启发和命名他的书的《地球上最伟大的表演:进化的证据》,并在其中引用查尔斯达尔文的物种起源[163][164][165] [166][167]。随后,他于2015年12月19日在伦敦温布利体育馆与 Nightwish 一起进行了现场表演。这场演唱会后来作为现场专辑/DVD 的一部分发行,专辑名为《精神的载体》。

备注

a. 汉密尔顿影响道金斯和影响可以看到整个道金斯的书《自私的基因》[26]。他们在牛津大学交上了朋友,2000年汉密尔顿去世后,道金斯为他写了讣告,并组织了一场世俗悼念仪式。[168]

b. 辩论以“创造论比进化论更有效”的动议被198票对115票击败而结束。[169][170]约翰 · 杜兰特在《从进化到创造: 欧洲的视角》一书中对进化论和创造论的批判历史观点。Sven Anderson, Arthus Peacocke), Aarhus Univ.新闻,奥尔胡斯,丹麦辩论不再提供该网站。有关两个部分的辩论录音,请参阅第一部分及第二部分。

参考文献

- ↑ 模板:Cite IEP

- ↑ "British scientists don't like Richard Dawkins, finds study that didn't even ask questions about Richard Dawkins". Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ↑ Elmhirst, Sophie (9 June 2015). "Is Richard Dawkins destroying his reputation?". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Richard Dawkins on Charles Darwin". BBC News. 14 February 2009.

- ↑ Blair, Olivia (29 January 2016). "Richard Dawkins dropped from science event for tweeting video mocking feminists and Islamists". The Independent.

- ↑ Fahy, Declan (2015). The New Celebrity Scientists: Out of the Lab and into the Limelight. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Dawkins, Richard 1941– – Contemporary Authors, New Revision Series". Encyclopedia.com. Cengage Learning. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard. "My mother is 100 today. She & my late father gave me an idyllic childhood. Her writings on that time are quoted in An Appetite for Wonder". Twitter. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard. "My beloved mother died today, a month short of her 103rd birthday. As a young wartime bride she was brave and adventurous. Her epic journey up Africa, illegally accompanying my father, is recounted in passages from her diary, reproduced in An Appetite for Wonder. Rest in Peace". Twitter. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ↑ Burke's Landed Gentry 17th edition, ed. L. G. Pine, 1952, 'Dawkins of Over Norton' pedigree

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Dawkins, Richard (11 December 2010). "Lives Remembered: John Dawkins". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (October 2004). The Ancestor's Tale. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-618-00583-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Tub-X6wydKgC.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard. "Brief Scientific Autobiography". Richard Dawkins Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Anthony, Andrew (15 September 2013). "Richard Dawkins: 'I don't think I am strident or aggressive'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Hattenstone, Simon (10 February 2003). "Darwin's child". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ "Richard Dawkins: The foibles of faith". BBC News. 12 October 2001. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ Pollard, Nick (April 1995). "High Profile". Third Way. 18 (3): 15. ISSN 0309-3492. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ Alister E. McGrath, Dawkins' God: From The Selfish Gene to The God Delusion (2015), p. 33

- ↑ "The Oundle Lecture Series". Oundle School. 2012b. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ↑ Preston, John (17 December 2006). "Preaching to the converted". Daily Telegraph (in British English). ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1966). Selective pecking in the domestic chick. bodleian.ox.ac.uk (DPhil thesis). University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Dawkins, Richard (1 January 2006). "Curriculum vitae" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1 January 2006). "Richard Dawkins: CV". Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2007. For direct link to media, see this link

- ↑ Schrage, Michael (July 1995). "Revolutionary Evolutionist". Wired. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1969). "A threshold model of choice behaviour". Animal Behaviour. 17 (1): 120–133. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(69)90120-1.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 ""Belief" interview". BBC. 5 April 2004. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ↑ Simonyi, Charles (15 May 1995). "Manifesto for the Simonyi Professorship". The University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "Aims of the Simonyi Professorship". 23 April 2008. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ↑ "Previous holders of The Simonyi Professorship". The University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ "Emeritus, Honorary and Wykeham Fellows". New College, Oxford. 2 May 2008. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "The Current Simonyi Professor: Richard Dawkins". The University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "Editorial Board". The Skeptics' Society. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ "The Dawkins Prize for Animal Conservation and Welfare". Balliol College, Oxford. 9 November 2007. Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ↑ Beckford, Martin; Khan, Urmee (24 October 2008). "Harry Potter fails to cast spell over Professor Richard Dawkins". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 4 November 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ "New university to rival Oxbridge will charge £18,000 a year". Sunday Telegraph. 5 June 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Ridley, Mark (2007). Richard Dawkins: How a Scientist Changed the Way We Think : Reflections by Scientists, Writers, and Philosophers. Oxford University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-19-921466-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=lH4sh2436rEC&q=%22evolutionary+biologist%22.

- ↑ Lloyd, Elisabeth Anne (1994). The structure and confirmation of evolutionary theory. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00046-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=hO8vHTSiBkAC.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1978). "Replicator Selection and the Extended Phenotype". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 47 (1): 61–76. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1978.tb01823.x. PMID 696023.

- ↑ "European Evolutionary Biologists Rally Behind Richard Dawkins's Extended Phenotype". Sciencedaily.com. 20 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay; Lewontin, Richard C. (1979). "The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. B. 205 (1161): 581–98. Bibcode:1979RSPSB.205..581G. doi:10.1098/rspb.1979.0086. PMID 42062.

- ↑ Hamilton, W.D. (1964). "The genetical evolution of social behaviour I and II". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 7 (1): 1–16, 17–52. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. PMID 5875341.

- ↑ Trivers, Robert (1971). "The evolution of reciprocal altruism". Quarterly Review of Biology. 46 (1): 35–57. doi:10.1086/406755. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1979). "Twelve Misunderstandings of Kin Selection" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 51 (2): 184–200. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1979.tb00682.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008.

- ↑ Thorpe, Vanessa (24 June 2012). "Richard Dawkins in furious row with EO Wilson over theory of evolution. Book review sparks war of words between grand old man of biology and Oxford's most high-profile Darwinist". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (24 May 2012). "The Descent of Edward Wilson". Prospect. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ↑ Williams, George Ronald (1996). The molecular biology of Gaia. Columbia University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-231-10512-5. https://archive.org/details/molecularbiology0000will. Extract of page 178

- ↑ Schneider, Stephen Henry (2004). Scientists debate gaia: the next century. MIT Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-262-19498-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=TOi1Cyj9h1UC. Extract of p. 72 -{zh-cn:互联网档案馆; zh-tw:網際網路檔案館; zh-hk:互聯網檔案館;}-的存檔,存档日期19 March 2015.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2000). Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 223. Bibcode 1998ursd.book.....D. ISBN 978-0-618-05673-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZudTchiioUoC. Extract of p. 223 -{zh-cn:互联网档案馆; zh-tw:網際網路檔案館; zh-hk:互聯網檔案館;}-的存檔,存档日期19 March 2015.

- ↑ Dover, Gabriel (2000). Dear Mr Darwin. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-1127-6.

- ↑ Williams, George C. (1966). Adaptation and Natural Selection. United States: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02615-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=wWZEq87CqO0C.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (2000). What Evolution Is. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04426-9.

- ↑ Midgley, Mary (1979). "Gene-Juggling". Philosophy. Vol. 54, no. 210. pp. 439–58. doi:10.1017/S0031819100063488. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1981). "In Defence of Selfish Genes". Philosophy. Vol. 56. pp. 556–73. doi:10.1017/S0031819100050580. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ↑ Midgley, Mary (2010). The solitary self: Darwin and the selfish gene. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-1-84465-253-2.

- ↑ Gross, Alan G. (2018). The Scientific Sublime: Popular Science Unravels the Mysteries of the Universe (Chapter 11: Richard Dawkins: The Mathematical Sublime). Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Brown, Andrew (1999). The Darwin Wars: How stupid genes became selfish genes. London: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-85144-0.

- ↑ Brown, Andrew (2000). The Darwin Wars: The Scientific Battle for the Soul of Man. Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-684-85145-7.

- ↑ Brockman, J. (1995). The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80359-3. https://archive.org/details/thirdculture00broc.

- ↑ Sterelny, K. (2007). Dawkins vs. Gould: Survival of the Fittest. Cambridge, UK: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-780-2.

- ↑ Morris, Richard (2001). The Evolutionists. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4094-0.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (24 January 1985). "Sociobiology: the debate continues". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel (1995). Darwin's Dangerous Idea. 2. United States: Simon & Schuster. pp. 32–36. Bibcode 1996Cmplx...2a..32M. ISBN 978-0-684-80290-9. https://archive.org/details/darwinsdangerous0000denn/page/32.

- ↑ Burman, J. T. (2012). "The misunderstanding of memes: Biography of an unscientific object, 1976–1999". Perspectives on Science. 20 (1): 75–104. doi:10.1162/POSC_a_00057.

- ↑ Kelly, Kevin (1994). Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World. United States: Addison-Wesley. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-201-48340-6.

- ↑ Shalizi, Cosma Rohilla. "Memes". Center for the Study of Complex Systems. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Laurent, John (1999). A Note on the Origin of 'Memes'/'Mnemes'. 3. pp. 14–19. http://cfpm.org/jom-emit/1999/vol3/laurent_j.html.

- ↑ van Driem, George (2007). "Symbiosism, Symbiomism and the Leiden definition of the meme". Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ↑ Gleick, James (15 February 2011). The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. Pantheon. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-375-42372-7.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard. "Our Mission". Richard Dawkins Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ↑ Lesley, Alison (26 January 2016). "Richard Dawkins' Atheist Organization Merges with Center for Inquiry". WorldReligionNews.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ Sheahen, Laura (October 2005). "The Problem with God: Interview with Richard Dawkins (2)". Beliefnet.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ↑ "Interview with Richard Dawkins". PBS. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- ↑ Van Biema, David (5 November 2006). "God vs. Science (3)". Time. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1 January 1997). "Is Science A Religion?". The Humanist. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ↑ Bingham, John (24 February 2012). "Richard Dawkins: I can't be sure God does not exist". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ↑ Lane, Christopher (2 February 2012). "Why Does Richard Dawkins Take Issue With Agnosticism?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ↑ Knapton, Sarah. "Richard Dawkins: 'I am a secular Christian'". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ Powell, Michael (19 September 2011). "A Knack for Bashing Orthodoxy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ↑ Hooper, Simon (9 November 2006). "The rise of the New Atheists". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Richard Dawkins on militant atheism". TED Conferences, LLC. February 2002. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1 October 2013). "The Four Horsemen DVD". Richard Dawkins Foundation (in English). Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Alexandra (27 November 2006). "Dawkins campaigns to keep God out of classroom". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Dawkins, Richard (21 June 2003). "The future looks bright". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ Powell, Michael (19 September 2011). "A Knack for Bashing Orthodoxy". The New York Times. p. 4. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Beckford, Martin (24 June 2010). "Richard Dawkins interested in setting up 'atheist free school'". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ↑ Garner, Richard (29 July 2010). "Gove welcomes atheist schools – Education News, Education". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ↑ "The God Delusion – Reviews". Richard Dawkins Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 July 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ↑ Eagleton·, Terry (19 October 2006). "Lunging, Flailing, Mispunching". London Review of Books. Vol. 28, no. 20. pp. 32–34. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (17 September 2007). "Do you have to read up on leprechology before disbelieving in them?". Richard Dawkins Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ↑ Jha, Alok (29 May 2007). "Scientists divided over alliance with religion". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ↑ Jha, Alok (26 December 2012). "Peter Higgs criticises Richard Dawkins over anti-religious 'fundamentalism'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Gray, John (2 October 2014). "The Closed Mind of Richard Dawkins". New Republic. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2006). "When Religion Steps on Science's Turf". Free Inquiry. Archived from the original on 19 April 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard. "How dare you call me a fundamentalist". Richard Dawkins Foundation. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ Malik, Nesrine (8 August 2013). "Richard Dawkins' tweets on Islam are as rational as the rants of an extremist Muslim cleric". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ↑ Blair, Olivia (29 January 2016). "Richard Dawkins dropped from science event for tweeting video mocking feminists and Islamists". The Independent. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ↑ Ruse, Michael. "Creationism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Laboratory, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

a Creationist is someone who believes in a god who is absolute creator of heaven and earth.

- ↑ Scott, Eugenie C (3 August 2009). "Creationism". Evolution vs. creationism: an introduction. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-520-26187-7. "The term 'creationism' to many people connotes the theological doctrine of special creationism: that God created the universe essentially as we see it today, and that this universe has not changed appreciably since that creation event. Special creationism includes the idea that God created living things in their present forms..."

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (9 March 2002). "A scientist's view". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ↑ Catalano, John (1 August 1996). "Book: The Blind Watchmaker". The University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ↑ Moyers, Bill (3 December 2004). "Now with Bill Moyers". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 16 May 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2006.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard; Coyne, Jerry (1 September 2005). "One side can be wrong". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ↑ Hall, Stephen S. (9 August 2005). "Darwin's Rottweiler". Discover magazine. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ↑ McGrath, Alister (2007). Dawkins' God : genes, memes, and the meaning of life (Reprinted ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell. p. i. ISBN 978-1405125383. https://archive.org/details/dawkinsgodgenesm0000mcgr.

- ↑ Swinford, Steven (19 November 2006). "Godless Dawkins challenges schools". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ↑ Bass, Thomas A. (1994). Reinventing the future: Conversations with the World's Leading Scientists. Addison Wesley. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-201-62642-1. https://archive.org/details/reinventingfutur00bass. Extract of page 118 -{zh-cn:互联网档案馆; zh-tw:網際網路檔案館; zh-hk:互聯網檔案館;}-的存檔,存档日期23 May 2020.

- ↑ "Our Honorary Associates". National Secular Society. 2005. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ↑ "The HSS Today". The Humanist Society of Scotland. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 April 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ↑ "Secular Coalition for America Advisory Board Biography". Secular.org. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ↑ "The International Academy Of Humanism – Humanist Laureates". Council for Secular Humanism. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ↑ "The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry – Fellows". The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ↑ "Humanism and Its Aspirations – Notable Signers". American Humanist Association. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ Chittenden, Maurice; Waite, Roger (23 December 2007). "Dawkins to preach atheism to US". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ↑ "The Bus Campaign". British Humanist Association. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ↑ "BBC: The Selfish Green". Richard Dawkins Foundation. 2 April 2007. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ The Great Ape Project. United Kingdom: Fourth Estate. 1993. ISBN 978-0-312-11818-1. https://archive.org/details/greatapeprojecte00cava.

- ↑ "3 Quarks Daily 2010 Prize in Science: Richard Dawkins has picked the three winners". 1 June 2010. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (22 March 2003). "Bin Laden's victory". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (18 November 2003). "While we have your attention, Mr President..." The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (19 November 2006). "From the Afterword". Herald Scotland. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ "Our supporters". Republic. 24 April 2010. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1989). "Endnotes. Chapter 1. Why are people?". The Selfish Gene (1st extra chapter) (2nd ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286092-7. https://archive.org/details/selfishgene00dawkrich.

- ↑ "Show your support – vote for the Liberal Democrats on May 6th". Libdems.org.uk. 3 May 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Flood, Alison (2021-04-20). "Richard Dawkins loses 'humanist of the year' title over trans comments". The Guardian (in English). Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ↑ "Overview". Campaign for a UN Parliamentary Assembly (in English). Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (16 December 2012). "Richard Dawkins". Twitter. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ Kutner, Jenny (8 December 2014). "Richard Dawkins: "Is There a Men's Rights Movement?"". Salon. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 Dawkins, Richard (9 July 1998). "Postmodernism Disrobed". Nature. 394 (6689): 141–43. Bibcode:1998Natur.394..141D. doi:10.1038/28089. For article with math symbols see this link -{zh-cn:互联网档案馆; zh-tw:網際網路檔案館; zh-hk:互聯網檔案館;}-的存檔,存档日期17 April 2016.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1998). Unweaving The Rainbow. United Kingdom: Penguin. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0-618-05673-6.

- ↑ Diamond, John (2001). Snake Oil and Other Preoccupations. United Kingdom: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-942833-6. https://archive.org/details/snakeoilotherpre0000diam.

- ↑ Harrison, David (5 August 2007). "New age therapies cause 'retreat from reason'". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Parker, Robin (27 January 2009). "C4 lines up Genius science series". Broadcast. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ↑ Knapton, Sarah (4 December 2014). "Asteroids could wipe out humanity, warn Richard Dawkins and Brian Cox". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "Durham salutes science, Shakespeare and social inclusion". Durham University News. 26 August 2005. Archived from the original on 3 February 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ↑ "Best-selling biologist and outspoken atheist among those honoured by University". University of Aberdeen. 1 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ↑ "Richard Dawkins, doctor 'honoris causa' per la Universitat de València". University of Valencia. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2009. Note: web page is in Spanish.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为frs的引用提供文字 - ↑ "American Humanist Association Board Statement Withdrawing Honor from Richard Dawkins". American Humanist Association. 19 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ↑ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ↑ Scripps Institution of Oceanography (7 April 2009). "Scripps Institution of Oceanography Honors Evolutionary Biologist, Richard Dawkins, in Public Ceremony and Lecture". Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ↑ Stiftung, Giordano Bruno (28 May 2007). "Deschner-Preis an Richard Dawkins". Humanistischer Pressedienst. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2008. Note: Web page in German.

- ↑ "CSICOP's 1992 Awards". Skeptical Inquirer. 17 (3): 236. 1993.

- ↑ "Q&A: Richard Dawkins". BBC News. 29 July 2004. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ↑ Herman, David (2004). "Public Intellectuals Poll". Prospect. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ↑ "The Top 100 Public Intellectuals". Prospect. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ↑ Dugdale, John (25 April 2013). "Richard Dawkins named world's top thinker in poll". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ "Galaxy British Book Awards — Winners & Shortlists 2007". Publishing News. 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ↑ Behe, Michael (3 May 2007). "Time Top 100". TIME. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- ↑ "Top 100 living geniuses". The Daily Telegraph. London. 28 October 2007. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ↑ Slack, Gordy (30 April 2005). "The atheist". Salon. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ↑ "Honorary FFRF Board Announced". Freedom From Religion Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ↑ "Sri Lankans name new fish genus after atheist Dawkins". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 15 July 2012. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ↑ Richard Dawkins, An Appetite for Wonder – The Making of a Scientist, p. 201.

- ↑ 154.0 154.1 McKie, Robin (25 July 2004). "Doctor Zoo". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 January 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ↑ Simpson, M.J. (2005). Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams. Justin, Charles & Co.. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-932112-35-1. https://archive.org/details/hitchhikerbiogra00simp. Chapter 15, p. 129

- ↑ "Richard Dawkins and Viscount of Bangor's sister Lalla Ward separate after 24 years". Belfast Telegraph. 17 July 2016. Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ↑ Dudding, Adam (12 February 2016). "Richard Dawkins suffers stroke, cancels New Zealand appearance". Fairfax New Zealand. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ Wahlquist, Calla (11 February 2016). "Richard Dawkins stroke forces delay of Australia and New Zealand tour". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ "Professor Dawkins on recovering from a mild stroke". Radio 4 Today. 24 May 2016. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (4 April 2016). "An April 4th Update from Richard". Richard Dawkins Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016. Audio file

- ↑ Staff. "BBC Educational and Documentary: Blind Watchmaker". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ↑ Staff. "Sex, Death and the Meaning of Life". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ "Nightwish's Next Album To Feature Guest Appearance By British Professor Richard Dawkins". Blabbermouth.net. 16 October 2014. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Nightwish's Tuomas Holopainen Gives 'Endless Forms Most Beautiful' Track-By-Track Breakdown (Video)". 17 March 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Shutt, Dan (21 December 2015). "Nightwish, Wembley Arena, gig review: Closing with The Greatest Show on Earth too much for sell-out audience to handle". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ↑ "Nightwish: track by track di "Endless Forms Most Beautiful"!". SpazioRock (in italiano). 17 March 2015. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ Schleutermann, Marcus (27 February 2015). "Nightwish – Food for Thought". EMP Rockinvasion (in English and Deutsch). Köln. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (3 October 2000). "Obituary by Richard Dawkins". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ↑ Critical-Historical Perspective on the Argument about Evolution and Creation, John Durant, in "From Evolution to Creation: A European Perspective (Eds. Sven Anderson, Arthus Peacocke), Aarhus Univ. Press, Aarhus, Denmark

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (12 March 2007). "1986 Oxford Union Debate: Richard Dawkins, John Maynard Smith". Richard Dawkins Foundation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

参考书目

- Dawkins, Richard (1989). The Selfish Gene (2nd ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286092-7.

- Dawkins, Richard (2006). The God Delusion. Transworld Publishers. ISBN 978-0-593-05548-9.

- Dawkins, Richard (2003). A Devil's Chaplain. Weidenfeld & Nicolson (United Kingdom and Commonwealth), Houghton Mifflin (United States). ISBN 978-0753817506.

- Dawkins, Richard (2015). Brief Candle in the Dark: My Life in Science. Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-59307-256-1.

- Grafen, Alan; Ridley, Mark (2006). Richard Dawkins: How A Scientist Changed the Way We Think. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929116-8. https://archive.org/details/richarddawkinsho00alan.

本中文词条由Moonscar、Ricky参与编译和审校,糖糖编辑,如有问题,欢迎在讨论页面留言。

本词条内容源自wikipedia及公开资料,遵守 CC3.0协议。