“伯努瓦·曼德布洛特 Benoit Mandelbrot”的版本间的差异

| 第74行: | 第74行: | ||

[[文件:Mandelbrot p1130861.jpg|缩略图|右|家庭背景和早期教育,(4:11)伯努瓦 曼德布洛特访谈,《Web of Stories》 144第1部分]] | [[文件:Mandelbrot p1130861.jpg|缩略图|右|家庭背景和早期教育,(4:11)伯努瓦 曼德布洛特访谈,《Web of Stories》 144第1部分]] | ||

| + | Mandelbrot was born in a [[Lithuanian Jews|Lithuanian Jewish]] family, in [[Warsaw]] during the [[Second Polish Republic]].<ref>{{Cite news|last=Hoffman|first=Jascha|date=2010-10-16|title=Benoît Mandelbrot, Novel Mathematician, Dies at 85 (Published 2010)|language=en-US|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/17/us/17mandelbrot.html|access-date=2020-11-20|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=21 January 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170121082521/http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/17/us/17mandelbrot.html|url-status=live}}</ref> His father made his living trading clothing; his mother was a dental surgeon. During his first two school years, he was tutored privately by an uncle who despised [[rote learning]]: "Most of my time was spent playing chess, reading maps and learning how to open my eyes to everything around me."<ref name="wolf">{{cite web |last=Mandelbrot |first=Benoît |title=The Wolf Prizes for Physics, ''A Maverick's Apprenticeship'' |publisher=Imperial College Press |year=2002 |url=http://users.math.yale.edu/~bbm3/web_pdfs/mavericksApprenticeship.pdf |access-date=23 April 2012 |archive-date=3 December 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131203024639/http://users.math.yale.edu/~bbm3/web_pdfs/mavericksApprenticeship.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1936, when he was 11, the family emigrated from Poland to France. The move, the [[World War II|war]], and his acquaintance with his father's brother, the mathematician [[Szolem Mandelbrojt]] (who had moved to Paris around 1920), further prevented a standard education. "The fact that my parents, as economic and political refugees, joined Szolem in France saved our lives," he writes.<ref name=Mandelbrot />{{rp|17}}<ref name="bbc_obit">{{cite news|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-11560101|title=BBC News – 'Fractal' mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot dies aged 85|date=17 October 2010|work=[[BBC Online]]|access-date=17 October 2010|archive-date=18 October 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101018045143/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-11560101|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mandelbrot was born in a Lithuanian Jewish family, in Warsaw during the Second Polish Republic.[14] His father made his living trading clothing; his mother was a dental surgeon. During his first two school years, he was tutored privately by an uncle who despised rote learning: "Most of my time was spent playing chess, reading maps and learning how to open my eyes to everything around me."[15] In 1936, when he was 11, the family emigrated from Poland to France. The move, the war, and his acquaintance with his father's brother, the mathematician Szolem Mandelbrojt (who had moved to Paris around 1920), further prevented a standard education. "The fact that my parents, as economic and political refugees, joined Szolem in France saved our lives," he writes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 曼德布洛特出生于波兰第二共和国时期,华沙的一个立陶宛犹太家庭。父亲以服装贸易为生,母亲是一名牙科医生。他入学后的前两年,一直由他叔叔私下辅导,这位叔叔尤其鄙视死记硬背的学习方法:“我的大部分时间都花在下棋,阅读地图和学习如何打开我的视角观察周围的一切。”后来1936年,他11岁时,一家人从波兰移民到了法国。这次移民,战争,和他父亲兄弟Szolem Mandelbrojt(数学家斯佐勒姆·曼德尔贝罗亚特,1920年左右移居巴黎)的接触,更进一步阻碍了他受到规范的教育。他曾写道:“我的父母作为经济和政治难民,在法国投靠了佐勒姆,因此而挽救了我们的生命。” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Mandelbrot attended the Lycée Rolin in Paris until the start of [[World War II]], when his family moved to [[Tulle]], France. He was helped by [[Rabbi]] [[David Feuerwerker]], the Rabbi of [[Brive-la-Gaillarde]], to continue his studies.<ref name=Mandelbrot/>{{rp|62–63}}<ref>Hemenway P. (2005) ''Divine proportion: Phi in art, nature and science''. Psychology Press. {{isbn|0-415-34495-6}}</ref> Much of France was occupied by the Nazis at the time, and Mandelbrot recalls this period: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mandelbrot attended the Lycée Rolin in Paris until the start of World War II, when his family moved to Tulle, France. He was helped by Rabbi David Feuerwerker, the Rabbi of Brive-la-Gaillarde, to continue his studies.[8]:62–63[17] Much of France was occupied by the Nazis at the time, and Mandelbrot recalls this period: | ||

| + | |||

| + | 曼德布罗特在巴黎罗兰公立中学学习,一直到第二次世界大战开始,后来他的家人搬到了法国的蒂勒。后来犹太教教士大卫·菲尔韦克Rabbi David Feuerwerker(布里夫拉盖勒德犹太教教士the Rabbi of Brive-la-Gaillarde)帮助他继续学业。当时法国大部分地区都被纳粹占领,曼德布罗特回忆起这段时期: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{quote|Our constant fear was that a sufficiently determined foe might report us to an authority and we would be sent to our deaths. This happened to a close friend from Paris, [[Zina Morhange]], a physician in a nearby county seat. Simply to eliminate the competition, another physician denounced her ... We escaped this fate. Who knows why?<ref name=Mandelbrot />{{rp|49}}}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our constant fear was that a sufficiently determined foe might report us to an authority and we would be sent to our deaths. This happened to a close friend from Paris, Zina Morhange, a physician in a nearby county seat. Simply to eliminate the competition, another physician denounced her ... We escaped this fate. Who knows why? | ||

| + | |||

| + | 我们一直担心的是,一旦敌人下定决心将我们报告给当局,等待我们的就是死刑。类似的事情就发生在巴黎的一位密友Zina Morhange深上,她曾是附近某个县城的医生。当时只是为了解决竞争对手,另一位医生就举报了她...而我们逃过了一劫。谁知道是为什么? | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In 1944, Mandelbrot returned to Paris, studied at the [[Lycée du Parc]] in [[Lyon]], and in 1945 to 1947 attended the [[École Polytechnique]], where he studied under [[Gaston Julia]] and [[Paul Lévy (mathematician)|Paul Lévy]]. From 1947 to 1949 he studied at California Institute of Technology, where he earned a master's degree in aeronautics.<ref name="guardian_obit" /> Returning to France, he obtained his [[Doctor of Philosophy|PhD degree]] in Mathematical Sciences at the [[University of Paris]] in 1952.<ref name="wolf" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1944, Mandelbrot returned to Paris, studied at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon, and in 1945 to 1947 attended the École Polytechnique, where he studied under Gaston Julia and Paul Lévy. From 1947 to 1949 he studied at California Institute of Technology, where he earned a master's degree in aeronautics.[2] Returning to France, he obtained his PhD degree in Mathematical Sciences at the University of Paris in 1952. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1944年,曼德布洛特回到巴黎,在里昂的帕克中学学习,并于1945年至1947年考上了巴黎综合理工学院,在加斯顿·朱莉亚Gaston Julia和保罗·列维Paul Lévy的指导下学习。之后的1947年到1949年,他就读于加利福尼亚理工学院,在那里获得了航空硕士学位。返回法国后,他于1952年在巴黎大学获得数学科学博士学位。 | ||

==Research career== | ==Research career== | ||

2020年12月26日 (六) 23:27的版本

此词条暂由彩云小译翻译,翻译字数共1902,未经人工整理和审校,带来阅读不便,请见谅。

伯努瓦 曼德布洛特 | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1924年11月20日 波兰华沙 |

| Died | 2010年10月14日 美国马萨诸塞州剑桥 |

| Nationality | 法国,美国,波兰 |

| Alma mater | 巴黎综合理工学院,加州理工学院,巴黎大学 |

| Known for | 曼德布罗集,混沌理论,分形,Zipf –曼德尔布洛特法则 |

| Spouse(s) | 阿利耶特·卡甘(1955-2010) |

| Awards | 法国荣誉军团勋章(1990年侠士·2006年警官),2003日本国际奖,1993沃尔夫奖,1989年哈维奖,1986年富兰克林奖章,1985年巴纳德奖章 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | 数学,空气动力学 |

| Institutions | 耶鲁大学,IBM公司,太平洋西北国家实验室 |

| Doctoral advisor | 保罗·皮埃尔·莱维 |

| Doctoral students | L-E. 卡维,尤金·法玛,肯·穆斯格雷夫,穆拉德·塔克 |

| Influences | 约翰内斯·开普勒,保罗·列维,索莱姆·曼德布罗特 |

| Influenced | 纳西姆·尼古拉斯·塔勒布 |

Benoit B.[n 1] Mandelbrot[n 2] (20 November 1924 – 14 October 2010) was a Polish-born French-American mathematician and polymath with broad interests in the practical sciences, especially regarding what he labeled as "the art of roughness" of physical phenomena and "the uncontrolled element in life".[3][4][5] He referred to himself as a "fractalist"[6] and is recognized for his contribution to the field of fractal geometry, which included coining the word "fractal", as well as developing a theory of "roughness and self-similarity" in nature.[7]

Benoit B.[n 1] Mandelbrot[n 2] (20 November 1924 – 14 October 2010) was a Polish-born French-American mathematician and polymath with broad interests in the practical sciences, especially regarding what he labeled as "the art of roughness" of physical phenomena and "the uncontrolled element in life".[5][6][7] He referred to himself as a "fractalist"[8] and is recognized for his contribution to the field of fractal geometry, which included coining the word "fractal", as well as developing a theory of "roughness and self-similarity" in nature.

伯努瓦 曼德布洛特(1924年11月20日至2010年10月14日)是波兰裔法国裔美国数学家和博学家,对实用科学有着广泛的兴趣。他将其称为物理现象的“粗糙艺术”和“生活中不受控制的元素”。他称自己为“分形主义者”,并因其对分形几何学领域的贡献而受到认可,其中包括创造了“分形Fractal”一词,并发展了自然界中的“ 粗糙度Roughness和 自相似性Self-similarity ”理论。

In 1936, while he was a child, Mandelbrot's family emigrated to France from Warsaw, Poland. After World War II ended, Mandelbrot studied mathematics, graduating from universities in Paris and the United States and receiving a master's degree in aeronautics from the California Institute of Technology. He spent most of his career in both the United States and France, having dual French and American citizenship. In 1958, he began a 35-year career at IBM, where he became an IBM Fellow, and periodically took leaves of absence to teach at Harvard University. At Harvard, following the publication of his study of U.S. commodity markets in relation to cotton futures, he taught economics and applied sciences.

In 1936, while he was a child, Mandelbrot's family emigrated to France from Warsaw, Poland. After World War II ended, Mandelbrot studied mathematics, graduating from universities in Paris and the United States and receiving a master's degree in aeronautics from the California Institute of Technology. He spent most of his career in both the United States and France, having dual French and American citizenship. In 1958, he began a 35-year career at IBM, where he became an IBM Fellow, and periodically took leaves of absence to teach at Harvard University. At Harvard, following the publication of his study of U.S. commodity markets in relation to cotton futures, he taught economics and applied sciences.

1936年,当曼德布罗特还是个孩子时,一家人从波兰华沙移民到了法国。第二次世界大战结束后,曼德布洛特学习了数学,从巴黎和美国的大学毕业,并获得了加州理工学院的航空硕士学位。他的职业生涯大部分时间都是在美国和法国度过,拥有法国和美国双重国籍。1958年,他在IBM开始了35年的职业生涯,并在那里成为了IBM研究员,定期请假到哈佛大学任教。在哈佛大学发表关于棉花期货的美国商品市场研究之后,他开始教授经济学和应用科学。

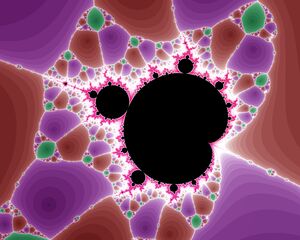

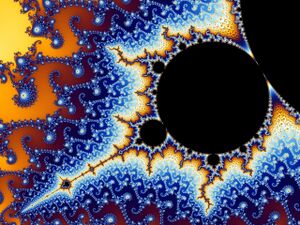

Because of his access to IBM's computers, Mandelbrot was one of the first to use computer graphics to create and display fractal geometric images, leading to his discovery of the Mandelbrot set in 1980. He showed how visual complexity can be created from simple rules. He said that things typically considered to be "rough", a "mess", or "chaotic", such as clouds or shorelines, actually had a "degree of order".[8] His math and geometry-centered research career included contributions to such fields as statistical physics, meteorology, hydrology, geomorphology, anatomy, taxonomy, neurology, linguistics, information technology, computer graphics, economics, geology, medicine, physical cosmology, engineering, chaos theory, econophysics, metallurgy, and the social sciences.[9]

Because of his access to IBM's computers, Mandelbrot was one of the first to use computer graphics to create and display fractal geometric images, leading to his discovery of the Mandelbrot set in 1980. He showed how visual complexity can be created from simple rules. He said that things typically considered to be "rough", a "mess", or "chaotic", such as clouds or shorelines, actually had a "degree of order".[10] His math and geometry-centered research career included contributions to such fields as statistical physics, meteorology, hydrology, geomorphology, anatomy, taxonomy, neurology, linguistics, information technology, computer graphics, economics, geology, medicine, physical cosmology, engineering, chaos theory, econophysics, metallurgy, and the social sciences.

由于曼德布罗特可以使用IBM的计算机,因此他是最早使用计算机图形来创建和显示分形几何图像的人之一,因此他于1980年发现了曼德布洛特集合。他展示了如何从简单的规则图形创建出视觉复杂性。他认为那些通常被认为是“粗糙”,“杂乱”或“混乱”的事物,例如云层或海岸线,实际上都具有“ 有序度Degree of order ”。他以数学和几何学为中心的延申研究领域包括了统计物理学,气象学,水文学,地貌学,解剖学,分类学,神经学,语言学,信息技术,计算机图形学,经济学,地质学,医学,物理宇宙学,工程学,混沌理论等领域的贡献 ,经济物理学,冶金学和社会科学。

Toward the end of his career, he was Sterling Professor of Mathematical Sciences at Yale University, where he was the oldest professor in Yale's history to receive tenure.[10] Mandelbrot also held positions at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Université Lille Nord de France, Institute for Advanced Study and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. During his career, he received over 15 honorary doctorates and served on many science journals, along with winning numerous awards. His autobiography, The Fractalist: Memoir of a Scientific Maverick, was published posthumously in 2012.

Toward the end of his career, he was Sterling Professor of Mathematical Sciences at Yale University, where he was the oldest professor in Yale's history to receive tenure.[12] Mandelbrot also held positions at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Université Lille Nord de France, Institute for Advanced Study and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. During his career, he received over 15 honorary doctorates and served on many science journals, along with winning numerous awards. His autobiography, The Fractalist: Memoir of a Scientific Maverick, was published posthumously in 2012.

在他职业生涯后期,他是耶鲁大学数学科学系的斯特林教授,在那里他被授予了耶鲁历史上最年长的终身教授职位。曼德布罗特还在西北太平洋国家实验室,里尔-北法兰西院校联盟,普林斯顿高等研究院和法国国家科学研究中心担任过职务。他的自传《分形主义者:一个科学特立独行者的回忆录》于2012年死后出版。

Early years 早年生活

Mandelbrot was born in a Lithuanian Jewish family, in Warsaw during the Second Polish Republic.[11] His father made his living trading clothing; his mother was a dental surgeon. During his first two school years, he was tutored privately by an uncle who despised rote learning: "Most of my time was spent playing chess, reading maps and learning how to open my eyes to everything around me."[12] In 1936, when he was 11, the family emigrated from Poland to France. The move, the war, and his acquaintance with his father's brother, the mathematician Szolem Mandelbrojt (who had moved to Paris around 1920), further prevented a standard education. "The fact that my parents, as economic and political refugees, joined Szolem in France saved our lives," he writes.[6]:17[13]

Mandelbrot was born in a Lithuanian Jewish family, in Warsaw during the Second Polish Republic.[14] His father made his living trading clothing; his mother was a dental surgeon. During his first two school years, he was tutored privately by an uncle who despised rote learning: "Most of my time was spent playing chess, reading maps and learning how to open my eyes to everything around me."[15] In 1936, when he was 11, the family emigrated from Poland to France. The move, the war, and his acquaintance with his father's brother, the mathematician Szolem Mandelbrojt (who had moved to Paris around 1920), further prevented a standard education. "The fact that my parents, as economic and political refugees, joined Szolem in France saved our lives," he writes.

曼德布洛特出生于波兰第二共和国时期,华沙的一个立陶宛犹太家庭。父亲以服装贸易为生,母亲是一名牙科医生。他入学后的前两年,一直由他叔叔私下辅导,这位叔叔尤其鄙视死记硬背的学习方法:“我的大部分时间都花在下棋,阅读地图和学习如何打开我的视角观察周围的一切。”后来1936年,他11岁时,一家人从波兰移民到了法国。这次移民,战争,和他父亲兄弟Szolem Mandelbrojt(数学家斯佐勒姆·曼德尔贝罗亚特,1920年左右移居巴黎)的接触,更进一步阻碍了他受到规范的教育。他曾写道:“我的父母作为经济和政治难民,在法国投靠了佐勒姆,因此而挽救了我们的生命。”

Mandelbrot attended the Lycée Rolin in Paris until the start of World War II, when his family moved to Tulle, France. He was helped by Rabbi David Feuerwerker, the Rabbi of Brive-la-Gaillarde, to continue his studies.[6]:62–63[14] Much of France was occupied by the Nazis at the time, and Mandelbrot recalls this period:

Mandelbrot attended the Lycée Rolin in Paris until the start of World War II, when his family moved to Tulle, France. He was helped by Rabbi David Feuerwerker, the Rabbi of Brive-la-Gaillarde, to continue his studies.[8]:62–63[17] Much of France was occupied by the Nazis at the time, and Mandelbrot recalls this period:

曼德布罗特在巴黎罗兰公立中学学习,一直到第二次世界大战开始,后来他的家人搬到了法国的蒂勒。后来犹太教教士大卫·菲尔韦克Rabbi David Feuerwerker(布里夫拉盖勒德犹太教教士the Rabbi of Brive-la-Gaillarde)帮助他继续学业。当时法国大部分地区都被纳粹占领,曼德布罗特回忆起这段时期:

/* Styling for Template:Quote */ .templatequote { overflow: hidden; margin: 1em 0; padding: 0 40px; } .templatequote .templatequotecite {

line-height: 1.5em; /* @noflip */ text-align: left; /* @noflip */ padding-left: 1.6em; margin-top: 0;

}

Our constant fear was that a sufficiently determined foe might report us to an authority and we would be sent to our deaths. This happened to a close friend from Paris, Zina Morhange, a physician in a nearby county seat. Simply to eliminate the competition, another physician denounced her ... We escaped this fate. Who knows why?

我们一直担心的是,一旦敌人下定决心将我们报告给当局,等待我们的就是死刑。类似的事情就发生在巴黎的一位密友Zina Morhange深上,她曾是附近某个县城的医生。当时只是为了解决竞争对手,另一位医生就举报了她...而我们逃过了一劫。谁知道是为什么?

In 1944, Mandelbrot returned to Paris, studied at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon, and in 1945 to 1947 attended the École Polytechnique, where he studied under Gaston Julia and Paul Lévy. From 1947 to 1949 he studied at California Institute of Technology, where he earned a master's degree in aeronautics.[15] Returning to France, he obtained his PhD degree in Mathematical Sciences at the University of Paris in 1952.[12]

In 1944, Mandelbrot returned to Paris, studied at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon, and in 1945 to 1947 attended the École Polytechnique, where he studied under Gaston Julia and Paul Lévy. From 1947 to 1949 he studied at California Institute of Technology, where he earned a master's degree in aeronautics.[2] Returning to France, he obtained his PhD degree in Mathematical Sciences at the University of Paris in 1952.

1944年,曼德布洛特回到巴黎,在里昂的帕克中学学习,并于1945年至1947年考上了巴黎综合理工学院,在加斯顿·朱莉亚Gaston Julia和保罗·列维Paul Lévy的指导下学习。之后的1947年到1949年,他就读于加利福尼亚理工学院,在那里获得了航空硕士学位。返回法国后,他于1952年在巴黎大学获得数学科学博士学位。

Research career

From 1949 to 1958, Mandelbrot was a staff member at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. During this time he spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he was sponsored by John von Neumann. In 1955 he married Aliette Kagan and moved to Geneva, Switzerland (to collaborate with Jean Piaget at the International Centre for Genetic Epistemology) and later to the Université Lille Nord de France.[16] In 1958 the couple moved to the United States where Mandelbrot joined the research staff at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York.[16] He remained at IBM for 35 years, becoming an IBM Fellow, and later Fellow Emeritus.[12]

According to Clarke, "the Mandelbrot set is indeed one of the most astonishing discoveries in the entire history of mathematics. Who could have dreamed that such an incredibly simple equation could have generated images of literally infinite complexity?" Clarke also notes an "odd coincidence

the name Mandelbrot, and the word "mandala"—for a religious symbol—which I'm sure is a pure coincidence, but indeed the Mandelbrot set does seem to contain an enormous number of mandalas. He joined the Department of Mathematics at Yale, and obtained his first tenured post in 1999, at the age of 75. At the time of his retirement in 2005, he was Sterling Professor of Mathematical Sciences.

根据克拉克的说法,“曼德尔布罗特集合确实是整个数学史上最惊人的发现之一。谁能想到这么简单的一个方程竟然能产生无限复杂的图像? ”克拉克还注意到了一个“奇怪的巧合”——曼德尔布洛特的名字,以及“曼荼罗”——意为宗教象征——我确信这纯粹是巧合,但事实上曼德尔布洛特集似乎包含了大量的曼荼罗。他加入了耶鲁大学数学系,并在1999年获得了他的第一个终身职位,那时他75岁。在他2005年退休的时候,他是数学科学的斯特林教席。

From 1951 onward, Mandelbrot worked on problems and published papers not only in mathematics but in applied fields such as information theory, economics, and fluid dynamics.

Mandelbrot created the first-ever "theory of roughness", and he saw "roughness" in the shapes of mountains, coastlines and river basins; the structures of plants, blood vessels and lungs; the clustering of galaxies. His personal quest was to create some mathematical formula to measure the overall "roughness" of such objects in nature.}}

曼德布洛特创立了有史以来第一个“粗糙理论” ,他看到了山脉、海岸线和河流盆地形状的“粗糙” ,看到了植物、血管和肺的结构,看到了星系的聚集。他个人的追求是创造一些数学公式来衡量这些物体在自然界中的整体“粗糙度”

Randomness in financial markets

In his paper titled How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension published in Science in 1967 Mandelbrot discusses self-similar curves that have Hausdorff dimension that are examples of fractals, although Mandelbrot does not use this term in the paper, as he did not coin it until 1975. The paper is one of Mandelbrot's first publications on the topic of fractals.

在他题为《英国海岸有多长?统计自相似性和分维数1967年发表在《科学》杂志上,曼德尔布洛特讨论了自相似曲线,这些曲线都有豪斯多夫维数,是分形的例子,尽管曼德尔布洛特在论文中没有使用这个术语,因为他直到1975年才造出这个术语。这篇论文是曼德布洛特关于分形主题的首批出版物之一。

Mandelbrot saw financial markets as an example of "wild randomness", characterized by concentration and long range dependence. He developed several original approaches for modelling financial fluctuations.[17]

In his early work, he found that the price changes in financial markets did not follow a Gaussian distribution, but rather Lévy stable distributions having infinite variance. He found, for example, that cotton prices followed a Lévy stable distribution with parameter α equal to 1.7 rather than 2 as in a Gaussian distribution. "Stable" distributions have the property that the sum of many instances of a random variable follows the same distribution but with a larger scale parameter.[18]

Mandelbrot emphasized the use of fractals as realistic and useful models for describing many "rough" phenomena in the real world. He concluded that "real roughness is often fractal and can be measured." and a maverick. His informal and passionate style of writing and his emphasis on visual and geometric intuition (supported by the inclusion of numerous illustrations) made The Fractal Geometry of Nature accessible to non-specialists. The book sparked widespread popular interest in fractals and contributed to chaos theory and other fields of science and mathematics.

曼德布洛特强调用分形作为现实和有用的模型来描述现实世界中的许多“粗糙”现象。他的结论是: “真实的粗糙度通常是分形的,可以测量。”还是个特立独行的人。他非正式和充满激情的写作风格和他对视觉和几何直觉的强调(通过大量插图的支持)使得《自然的分形几何学》对非专业人士来说易于理解。这本书激发了人们对分形的广泛兴趣,并促成了混沌理论和其他领域的科学和数学。

Developing "fractal geometry" and the Mandelbrot set

Mandelbrot also put his ideas to work in cosmology. He offered in 1974 a new explanation of Olbers' paradox (the "dark night sky" riddle), demonstrating the consequences of fractal theory as a sufficient, but not necessary, resolution of the paradox. He postulated that if the stars in the universe were fractally distributed (for example, like Cantor dust), it would not be necessary to rely on the Big Bang theory to explain the paradox. His model would not rule out a Big Bang, but would allow for a dark sky even if the Big Bang had not occurred.

曼德布洛特也将他的想法应用于宇宙学。1974年,他对奥尔伯斯悖论(“黑暗的夜空”之谜)提出了新的解释,证明了分形理论的结果是解决这一悖论的充分而非必要的方法。他假设,如果宇宙中的恒星是分散分布的(例如,康托尔尘埃) ,就没有必要依靠大爆炸理论来解释这一悖论。他的模型不能排除宇宙大爆炸的可能性,但是即使宇宙大爆炸没有发生,也可以考虑到黑暗的天空。

As a visiting professor at Harvard University, Mandelbrot began to study fractals called Julia sets that were invariant under certain transformations of the complex plane. Building on previous work by Gaston Julia and Pierre Fatou, Mandelbrot used a computer to plot images of the Julia sets. While investigating the topology of these Julia sets, he studied the Mandelbrot set which was introduced by him in 1979. In 1982, Mandelbrot expanded and updated his ideas in The Fractal Geometry of Nature.[19] This influential work brought fractals into the mainstream of professional and popular mathematics, as well as silencing critics, who had dismissed fractals as "program artifacts".

Mandelbrot's awards include the Wolf Prize for Physics in 1993, the Lewis Fry Richardson Prize of the European Geophysical Society in 2000, the Japan Prize in 2003, and the Einstein Lectureship of the American Mathematical Society in 2006.

曼德布洛特获得的奖项包括1993年的沃尔夫物理奖、2000年欧洲地球物理学会的刘易斯 · 弗莱 · 理查森奖、2003年的日本奖以及2006年的美国数学学会爱因斯坦讲师奖。

Mandelbrot speaking about the Mandelbrot set, during his acceptance speech for the Légion d'honneur in 2006

Mandelbrot speaking about the Mandelbrot set, during his acceptance speech for the Légion d'honneur in 2006

The small asteroid 27500 Mandelbrot was named in his honor. In November 1990, he was made a Chevalier in France's Legion of Honour. In December 2005, Mandelbrot was appointed to the position of Battelle Fellow at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Mandelbrot was promoted to an Officer of the Legion of Honour in January 2006. An honorary degree from Johns Hopkins University was bestowed on Mandelbrot in the May 2010 commencement exercises.

小行星27500 Mandelbrot 以他的名字命名。1990年11月,他被授予法国法国荣誉军团勋章骑士称号。2005年12月,曼德尔布洛特被任命为太平洋西北国家实验室的巴特尔研究员。2006年1月,曼德尔布洛特被提升为法国荣誉军团勋章安全委员会官员。在2010年5月的毕业典礼上,曼德尔布洛特获得了约翰·霍普金斯大学的荣誉学位。

In 1975, Mandelbrot coined the term fractal to describe these structures and first published his ideas, and later translated, Fractals: Form, Chance and Dimension.[20] According to computer scientist and physicist Stephen Wolfram, the book was a "breakthrough" for Mandelbrot, who until then would typically "apply fairly straightforward mathematics ... to areas that had barely seen the light of serious mathematics before".[8] Wolfram adds that as a result of this new research, he was no longer a "wandering scientist", and later called him "the father of fractals":

A partial list of awards received by Mandelbrot:

曼德布洛特获得的部分奖项:

/* Styling for Template:Quote */ .templatequote { overflow: hidden; margin: 1em 0; padding: 0 40px; } .templatequote .templatequotecite { line-height: 1.5em; /* @noflip */ text-align: left; /* @noflip */ padding-left: 1.6em; margin-top: 0; }

Wolfram briefly describes fractals as a form of geometric repetition, "in which smaller and smaller copies of a pattern are successively nested inside each other, so that the same intricate shapes appear no matter how much you zoom in to the whole. Fern leaves and Romanesco broccoli are two examples from nature."[8] He points out an unexpected conclusion:

/* Styling for Template:Quote */ .templatequote { overflow: hidden; margin: 1em 0; padding: 0 40px; } .templatequote .templatequotecite { line-height: 1.5em; /* @noflip */ text-align: left; /* @noflip */ padding-left: 1.6em; margin-top: 0; }

Mandelbrot used the term "fractal" as it derived from the Latin word "fractus", defined as broken or shattered glass. Using the newly developed IBM computers at his disposal, Mandelbrot was able to create fractal images using graphic computer code, images that an interviewer described as looking like "the delirious exuberance of the 1960s psychedelic art with forms hauntingly reminiscent of nature and the human body". He also saw himself as a "would-be Kepler", after the 17th-century scientist Johannes Kepler, who calculated and described the orbits of the planets.[21]

Mandelbrot, however, never felt he was inventing a new idea. He describes his feelings in a documentary with science writer Arthur C. Clarke:

/* Styling for Template:Quote */ .templatequote { overflow: hidden; margin: 1em 0; padding: 0 40px; } .templatequote .templatequotecite { line-height: 1.5em; /* @noflip */ text-align: left; /* @noflip */ padding-left: 1.6em; margin-top: 0; }

According to Clarke, "the Mandelbrot set is indeed one of the most astonishing discoveries in the entire history of mathematics. Who could have dreamed that such an incredibly simple equation could have generated images of literally infinite complexity?" Clarke also notes an "odd coincidence

the name Mandelbrot, and the word "mandala"—for a religious symbol—which I'm sure is a pure coincidence, but indeed the Mandelbrot set does seem to contain an enormous number of mandalas.[22]

Mandelbrot left IBM in 1987, after 35 years and 12 days, when IBM decided to end pure research in his division.[23] He joined the Department of Mathematics at Yale, and obtained his first tenured post in 1999, at the age of 75.[24] At the time of his retirement in 2005, he was Sterling Professor of Mathematical Sciences.

Fractals and the "theory of roughness"

Mandelbrot created the first-ever "theory of roughness", and he saw "roughness" in the shapes of mountains, coastlines and river basins; the structures of plants, blood vessels and lungs; the clustering of galaxies. His personal quest was to create some mathematical formula to measure the overall "roughness" of such objects in nature.[6]:xi He began by asking himself various kinds of questions related to nature:

/* Styling for Template:Quote */ .templatequote { overflow: hidden; margin: 1em 0; padding: 0 40px; } .templatequote .templatequotecite {

line-height: 1.5em; /* @noflip */ text-align: left; /* @noflip */ padding-left: 1.6em; margin-top: 0;}

In his paper titled How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension published in Science in 1967 Mandelbrot discusses self-similar curves that have Hausdorff dimension that are examples of fractals, although Mandelbrot does not use this term in the paper, as he did not coin it until 1975. The paper is one of Mandelbrot's first publications on the topic of fractals.[25][26]

Mandelbrot emphasized the use of fractals as realistic and useful models for describing many "rough" phenomena in the real world. He concluded that "real roughness is often fractal and can be measured."[6]:296 Although Mandelbrot coined the term "fractal", some of the mathematical objects he presented in The Fractal Geometry of Nature had been previously described by other mathematicians. Before Mandelbrot, however, they were regarded as isolated curiosities with unnatural and non-intuitive properties. Mandelbrot brought these objects together for the first time and turned them into essential tools for the long-stalled effort to extend the scope of science to explaining non-smooth, "rough" objects in the real world. His methods of research were both old and new:

/* Styling for Template:Quote */ .templatequote { overflow: hidden; margin: 1em 0; padding: 0 40px; } .templatequote .templatequotecite {

line-height: 1.5em; /* @noflip */ text-align: left; /* @noflip */ padding-left: 1.6em; margin-top: 0;}

Fractals are also found in human pursuits, such as music, painting, architecture, and stock market prices. Mandelbrot believed that fractals, far from being unnatural, were in many ways more intuitive and natural than the artificially smooth objects of traditional Euclidean geometry:

Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line.

—Mandelbrot, in his introduction to The Fractal Geometry of Nature

Mandelbrot has been called an artist, and a visionary[27] and a maverick.[28] His informal and passionate style of writing and his emphasis on visual and geometric intuition (supported by the inclusion of numerous illustrations) made The Fractal Geometry of Nature accessible to non-specialists. The book sparked widespread popular interest in fractals and contributed to chaos theory and other fields of science and mathematics.

Mandelbrot died from pancreatic cancer at the age of 85 in a hospice in Cambridge, Massachusetts on 14 October 2010. Reacting to news of his death, mathematician Heinz-Otto Peitgen said: "[I]f we talk about impact inside mathematics, and applications in the sciences, he is one of the most important figures of the last fifty years." Nicolas Sarkozy, President of France at the time of Mandelbrot's death, said Mandelbrot had "a powerful, original mind that never shied away from innovating and shattering preconceived notions [... h]is work, developed entirely outside mainstream research, led to modern information theory." Mandelbrot's obituary in The Economist points out his fame as "celebrity beyond the academy" and lauds him as the "father of fractal geometry".

2010年10月14日,曼德尔布洛特在马萨诸塞州剑桥的一家临终关怀胰腺癌去世,享年85岁。数学家海因茨-奥托 · 佩特根在听到他去世的消息后说: “如果我们谈论数学内部的影响,以及在科学中的应用,他是过去50年来最重要的人物之一。”曼德布洛特去世时的法国总统尼古拉•萨科齐(Nicolas Sarkozy)表示,曼德布洛特“拥有强大的、独创的头脑,从不回避创新和打破先入为主的观念[ ... ... 他是工作,完全在主流研究之外发展起来,导致了现代信息理论的产生。”曼德布洛特在《经济学人》上发表的讣告指出,他是“学术之外的名人” ,并称赞他是“分形几何之父”。

Mandelbrot also put his ideas to work in cosmology. He offered in 1974 a new explanation of Olbers' paradox (the "dark night sky" riddle), demonstrating the consequences of fractal theory as a sufficient, but not necessary, resolution of the paradox. He postulated that if the stars in the universe were fractally distributed (for example, like Cantor dust), it would not be necessary to rely on the Big Bang theory to explain the paradox. His model would not rule out a Big Bang, but would allow for a dark sky even if the Big Bang had not occurred.[29]

Best-selling essayist-author Nassim Nicholas Taleb has remarked that Mandelbrot's book The (Mis)Behavior of Markets is in his opinion "The deepest and most realistic finance book ever published".

最畅销的散文作家兼作家纳西姆·尼可拉斯·塔雷伯 · 曼德布洛特评论说,曼德布洛特的著作《市场的(错误)行为》是他认为“有史以来最深刻、最现实的金融著作”。

Awards and honors

Mandelbrot's awards include the Wolf Prize for Physics in 1993, the Lewis Fry Richardson Prize of the European Geophysical Society in 2000, the Japan Prize in 2003,[30] and the Einstein Lectureship of the American Mathematical Society in 2006.

The small asteroid 27500 Mandelbrot was named in his honor. In November 1990, he was made a Chevalier in France's Legion of Honour. In December 2005, Mandelbrot was appointed to the position of Battelle Fellow at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.[31] Mandelbrot was promoted to an Officer of the Legion of Honour in January 2006.[32] An honorary degree from Johns Hopkins University was bestowed on Mandelbrot in the May 2010 commencement exercises.[33]

A partial list of awards received by Mandelbrot:[34]

“ padding-right: 2em”

- 2004 Best Business Book of the Year Award

- AMS Einstein Lectureship

- Barnard Medal

- Caltech Service

- Casimir Funk Natural Sciences Award

- Fellow, American Geophysical Union

- Harvey Prize (1989)

- Honda Prize

- Humboldt Preis

- IBM Fellowship

- Japan Prize (2003)

- Légion d'honneur (Legion of Honour)

- Lewis Fry Richardson Medal

- Medaglia della Presidenza della Repubblica Italiana

- Médaille de Vermeil de la Ville de Paris

- Nevada Prize

- Member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters.[37]

- Science for Art

- Sven Berggren-Priset

- Władysław Orlicz Prize

- Wolf Foundation Prize for Physics (1993)

Legacy

Mandelbrot died from pancreatic cancer at the age of 85 in a hospice in Cambridge, Massachusetts on 14 October 2010.[38][39] Reacting to news of his death, mathematician Heinz-Otto Peitgen said: "[I]f we talk about impact inside mathematics, and applications in the sciences, he is one of the most important figures of the last fifty years."[38]

Chris Anderson, TED conference curator, described Mandelbrot as "an icon who changed how we see the world".[40] Nicolas Sarkozy, President of France at the time of Mandelbrot's death, said Mandelbrot had "a powerful, original mind that never shied away from innovating and shattering preconceived notions [... h]is work, developed entirely outside mainstream research, led to modern information theory."[41] Mandelbrot's obituary in The Economist points out his fame as "celebrity beyond the academy" and lauds him as the "father of fractal geometry".[42]

Best-selling essayist-author Nassim Nicholas Taleb has remarked that Mandelbrot's book The (Mis)Behavior of Markets is in his opinion "The deepest and most realistic finance book ever published".[7]

Bibliography

in English

- Fractals: Form, Chance and Dimension, 1977, 2020

- Fractals and Scaling in Finance: Discontinuity, Concentration, Risk. Selecta Volume E, 1997 by Benoit B. Mandelbrot and R.E. Gomory

- Fractales, hasard et finance, 1959-1997, 1 November 1998

- Multifractals and 1/ƒ Noise: Wild Self-Affinity in Physics (1963–1976) (Selecta; V.N) 18 January 1999 by J.M. Berger and Benoit B. Mandelbrot

- Gaussian Self-Affinity and Fractals: Globality, The Earth, 1/f Noise, and R/S (Selected Works of Benoit B. Mandelbrot) 14 December 2001 by Benoit Mandelbrot and F.J. Damerau

- Fractals and Chaos: The Mandelbrot Set and Beyond, 9 January 2004

- The Misbehavior of Markets: A Fractal View of Financial Turbulence, 2006 by Benoit Mandelbrot and Richard L. Hudson

- The Fractalist: Memoir of a Scientific Maverick, 2014

In French

- La forme d'une vie. Mémoires (1924-2010) by Benoît Mandelbrot (Author), Johan-Frédérik Hel Guedj (Translator)

References in popular culture

- In 2004, the American singer-songwriter Jonathan Coulton wrote "Mandelbrot Set". Formerly, it contained the lines "Mandelbrot's in heaven / at least he will be when he's dead / right now he's still alive and teaching math at Yale". Live performances after Mandelbrot's passing in 2010 feature only the first line and a brief rock instrumental.

- In 2007, the author Laura Ruby published "The Chaos King," which includes a character named Mandelbrot and discussion of chaos theory.

- In 2017, Zach Weinersmith' webcomic, Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, portrayed Mandelbrot.[43]

- In 2017, Liz Ziemska published a novella, Mandelbrot The Magnificent, a fictional account of how Mandelbrot saved his family during WWII

See also

Category:1924 births

类别: 1924出生

Category:2010 deaths

分类: 2010年死亡人数

Category:20th-century American mathematicians

范畴: 20世纪美国数学家

Category:21st-century French mathematicians

范畴: 21世纪法国数学家

Category:20th-century American economists

类别: 20世纪美国经济学家

Category:21st-century American economists

类别: 21世纪美国经济学家

Category:Alexander von Humboldt Fellows

类别: 亚历山大·冯·洪堡研究员

Category:California Institute of Technology alumni

类别: 加州理工学院校友

Category:Chaos theorists

范畴: 混沌理论家

Category:Deaths from cancer in Massachusetts

分类: 马萨诸塞州癌症死亡人数

Category:Deaths from pancreatic cancer

分类: 死于胰腺癌

Category:École Polytechnique alumni

类别: 巴黎综合理工学院校友

Category:Fellows of the American Geophysical Union

类别: 美国地球物理联盟研究员

Category:Fellows of the American Statistical Association

类别: 美国统计协会研究员

Notes

Category:Fellows of the Econometric Society

类别: 经济计量学会研究员

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为Mandelbrot's_name的引用提供文字- ↑ Pronounced 模板:IPAc-en 模板:Respell in English.[1] When speaking in French, Mandelbrot pronounced his name 模板:IPA-fr.[2]

Category:Fellows of the American Physical Society

类别: 美国物理学会会员

Category:French emigrants to the United States

类别: 移居美国的法国移民

References

Category:French scientists

分类: 法国科学家

- ↑ 模板:OED

- ↑ Recording of the ceremony on 11 September 2006 at which Mandelbrot received the insignia for an Officer of the Légion d'honneur.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)- ↑ Benoit Mandelbrot: Fractals and the art of roughness -{zh-cn:互联网档案馆; zh-tw:網際網路檔案館; zh-hk:互聯網檔案館;}-的存檔,存档日期14 April 2016.. ted.com (February 2010)

- ↑ Hudson & Mandelbrot, Prelude, page xviii

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为Mandelbrot的引用提供文字- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gomory, R. (2010). "Benoît Mandelbrot (1924–2010)". Nature. 468 (7322): 378. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..378G. doi:10.1038/468378a. PMID 21085164. S2CID 4393964.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Wolfram, Stephen. "The Father of Fractals", Wall Street Journal, 22 November 2012

- ↑ list includes specific sciences mentioned in Hudson & Mandelbrot, the Prelude, p. xvi, and p. 26

- ↑ Steve Olson (November–December 2004). "The Genius of the Unpredictable". Yale Alumni Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ↑ Hoffman, Jascha (16 October 2010). "Benoît Mandelbrot, Novel Mathematician, Dies at 85 (Published 2010)". The New York Times (in English). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Mandelbrot, Benoît (2002). "The Wolf Prizes for Physics, A Maverick's Apprenticeship" (PDF). Imperial College Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ "BBC News – 'Fractal' mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot dies aged 85". BBC Online. 17 October 2010. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Hemenway P. (2005) Divine proportion: Phi in art, nature and science. Psychology Press.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为guardian_obit的引用提供文字- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Barcellos, Anthony (1984). "Mathematical People, Interview of B. B. Mandelbrot" (PDF). Birkhaüser.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)- ↑ Rama Cont (19 April 2010). "Mandelbrot, Benoit". Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470061602.eqf01006. ISBN 9780470057568.

- ↑ "New Scientist, 19 April 1997". Newscientist.com. 19 April 1997. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ The Fractal Geometry of Nature, by Benoît Mandelbrot; W H Freeman & Co, 1982;

- ↑ Fractals: Form, Chance and Dimension, by Benoît Mandelbrot; W H Freeman and Co, 1977;

- ↑ Ivry, Benjamin. "Benoit Mandelbrot Influenced Art and Mathematics", Forward, 17 November 2012

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为Clarke的引用提供文字- ↑ Mandelbrot, Benoît; Bernard Sapoval; Daniel Zajdenweber (May 1998). "Web of Stories • Benoît Mandelbrot • IBM: background and policies". Web of Stories. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Tenner, Edward (16 October 2010). "Benoît Mandelbrot the Maverick, 1924–2010". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ "Dr. Mandelbrot traced his work on fractals to a question he first encountered as a young researcher: how long is the coast of Britain?": Benoit Mandelbrot (1967). "Benoît Mandelbrot, Novel Mathematician, Dies at 85", The New York Times.

- ↑ Mandelbrot, Benoit B. (5 May 1967). "How long is the coast of Britain? Statistical self-similarity and fractional dimension" (PDF). Science. 156 (3775): 636–638. Bibcode:1967Sci...156..636M. doi:10.1126/science.156.3775.636. PMID 17837158. S2CID 15662830.

- ↑ Devaney, Robert L. (2004). ""Mandelbrot's Vision for Mathematics" in Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics. Volume 72.1" (PDF). American Mathematical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2006. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ↑ Jersey, Bill (24 April 2005). "A Radical Mind". Hunting the Hidden Dimension. NOVA/ PBS. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ↑ Galaxy Map Hints at Fractal Universe, by Amanda Gefter; New Scientist; 25 June 2008

- ↑ Laureates of the Japan Prize. japanprize.jp

- ↑ "PNNL press release: Mandelbrot joins Pacific Northwest National Laboratory". Pnl.gov. 16 February 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "Légion d'honneur announcement of promotion of Mandelbrot to officier" (in français). Legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "Six granted honorary degrees, Society of Scholars inductees recognized". Gazette.jhu.edu. 7 June 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Mandelbrot, Benoit B. (2 February 2006). "Vita and Awards (Word document)". Retrieved 6 January 2007. Retrieved from Internet Archive 15 December 2013.

- ↑ View/Search Fellows of the ASA, accessed 20 August 2016.

- ↑ "APS Fellow Archive". APS. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ↑ "Gruppe 1: Matematiske fag" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)- ↑ 38.0 38.1 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为nyt_obit的引用提供文字- ↑ "Benoît Mandelbrot, fractals pioneer, dies". United Press International. 16 October 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "Mandelbrot, father of fractal geometry, dies". The Gazette. Archived from the original on 19 October 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ "Sarkozy rend hommage à Mandelbrot" [Sarkozy pays homage to Mandelbrot]. Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 17 October 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)- ↑ Benoît Mandelbrot's obituary. The Economist (21 October 2010)

- ↑ "Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal – Mandelbrot".

Category:Harvard University people

类别: 哈佛大学的人

Category:IBM employees

类别: IBM 员工

Bibliography

Category:IBM Fellows

类别: IBM Fellows

- Hudson, Richard L.; Mandelbrot, Benoît B. (2004). The (Mis)Behavior of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin, and Reward. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04355-2. https://archive.org/details/misbehaviorofmar00beno.

Category:IBM Research computer scientists

类别: IBM 研究计算机科学家

Category:Institute for Advanced Study visiting scholars

类别: 高级研究所访问学者

Further reading

Category:Jewish French scientists

类别: 犹太法国科学家

- Mandelbrot, Benoit B. (2010). The Fractalist, Memoir of a Scientific Maverick. New York: Vintage Books, Division of Random House.

Category:Members of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters

类别: 挪威科学与文学学会成员

- Mandelbrot, Benoît B. (1983). The Fractal Geometry of Nature. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-1186-5.

Category:Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

类别: 美国国家科学院院士

- Heinz-Otto Peitgen, Hartmut Jürgens, Dietmar Saupe and Cornelia Zahlten: Fractals: An Animated Discussion (63 min video film, interviews with Benoît Mandelbrot and Edward Lorenz, computer animations), W.H. Freeman and Company, 1990. (re-published by Films for the Humanities & Sciences, )

Category:Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

类别: 美国法国荣誉军团勋章协会官员

- Mandelbrot, Benoit B. (1997) Fractals and Scaling in Finance: Discontinuity, Concentration, Risk, Springer.

Category:Polish emigrants to France

类别: 移居法国的波兰移民

- Mandelbrot, Benoît (February 1999). "A Multifractal Walk down Wall Street". Scientific American. 280 (2): 70. Bibcode:1999SciAm.280b..70M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0299-70.

Category:Polish emigrants to the United States

类别: 移居美国的波兰移民

- Mandelbrot, Benoit B., Gaussian Self-Affinity and Fractals, Springer: 2002.

Category:Polish Jews

分类: 波兰犹太人

- Mandelbrot, Benoît; Taleb, Nassim (23 March 2006). "A focus on the exceptions that prove the rule". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

Category:University of Paris alumni

类别: 巴黎大学校友

- "Hunting the Hidden Dimension: mysteriously beautiful fractals are shaking up the world of mathematics and deepening our understanding of nature", NOVA, WGBH Educational Foundation, Boston for PBS, first aired 28 October 2008.

Category:Wolf Prize in Physics laureates

类别: 沃尔夫物理学奖获得者

- Frame, Michael; Cohen, Nathan (2015). Benoit Mandelbrot: A Life in Many Dimensions. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-981-4366-06-9.

Category:Yale University faculty

类别: 耶鲁学院

- Mandelbrot, B. (1959) Variables et processus stochastiques de Pareto-Levy, et la repartition des revenus. Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris, 249, 613–615.

Category:Yale Sterling Professors

分类: 耶鲁斯特林教授

- Mandelbrot, B. (1960) The Pareto-Levy law and the distribution of income. International Economic Review, 1, 79–106.

Category:20th-century French mathematicians

范畴: 20世纪法国数学家

- Mandelbrot, B. (1961) Stable Paretian random functions and the multiplicative variation of income. Econometrica, 29, 517–543.

Category:21st-century American mathematicians

范畴: 21世纪美国数学家

This page was moved from wikipedia:en:Benoit Mandelbrot. Its edit history can be viewed at 曼德布洛特/edithistory

- 有参考文献错误的页面

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Webarchive模板wayback链接

- CS1 English-language sources (en)

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1 français-language sources (fr)

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- Articles with short description

- Use dmy dates from February 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with hCards

- No local image but image on Wikidata

- 保护状态与保护标志不符的页面

- 待整理页面