“盖亚假说”的版本间的差异

(→假说提出) |

(→参考文献) |

||

| 第330行: | 第330行: | ||

*{{cite book |author=Jaworski, Helan |title=Le Géon ou la Terre vivante |publisher=Librairie Gallimard |location=Paris |date=1928 }} | *{{cite book |author=Jaworski, Helan |title=Le Géon ou la Terre vivante |publisher=Librairie Gallimard |location=Paris |date=1928 }} | ||

*Lovelock, James. ''The Independent''. [https://web.archive.org/web/20060408121826/http://comment.independent.co.uk/commentators/article338830.ece The Earth is about to catch a morbid fever], 16 January 2006. | *Lovelock, James. ''The Independent''. [https://web.archive.org/web/20060408121826/http://comment.independent.co.uk/commentators/article338830.ece The Earth is about to catch a morbid fever], 16 January 2006. | ||

| − | *{{cite journal |author=Kleidon, Axel |title=Beyond Gaia: Thermodynamics of Life and Earth system functioning |journal=Climatic Change |volume=66 |issue=3 |pages=271–319 |date=2004 |doi=10.1023/B:CLIM.0000044616.34867.ec | + | *{{cite journal |author=Kleidon, Axel |title=Beyond Gaia: Thermodynamics of Life and Earth system functioning |journal=Climatic Change |volume=66 |issue=3 |pages=271–319 |date=2004 |doi=10.1023/B:CLIM.0000044616.34867.ec }} |

*{{cite book |author=Lovelock, James |date=1995 |title=The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth |isbn=978-0-393-31239-3 |publisher=Norton |location=New York}} | *{{cite book |author=Lovelock, James |date=1995 |title=The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth |isbn=978-0-393-31239-3 |publisher=Norton |location=New York}} | ||

*{{cite book |author=Lovelock, James |date=2000 |title=Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth |isbn=978-0-19-286218-1 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford }} | *{{cite book |author=Lovelock, James |date=2000 |title=Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth |isbn=978-0-19-286218-1 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford }} | ||

| 第341行: | 第341行: | ||

*{{cite journal |author=Staley M |title=Darwinian selection leads to Gaia |journal=J. Theor. Biol. |volume=218 |issue=1 |pages=35–46 |date=September 2002 |pmid=12297068 |doi=10.1006/jtbi.2002.3059 }} | *{{cite journal |author=Staley M |title=Darwinian selection leads to Gaia |journal=J. Theor. Biol. |volume=218 |issue=1 |pages=35–46 |date=September 2002 |pmid=12297068 |doi=10.1006/jtbi.2002.3059 }} | ||

*{{cite book |author=Schneider, Stephen Henry |title=Scientists debate Gaia: the next century |publisher=MIT Press |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |date=2004|isbn=978-0-262-19498-3 }} | *{{cite book |author=Schneider, Stephen Henry |title=Scientists debate Gaia: the next century |publisher=MIT Press |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |date=2004|isbn=978-0-262-19498-3 }} | ||

| − | *{{cite book |author=Thomas, Lewis G. |title=The Lives of a Cell; Notes of a Biology Watcher |url=https://archive.org/details/livesofcellnotes00thomrich |url-access=registration |publisher= | + | *{{cite book |author=Thomas, Lewis G. |title=The Lives of a Cell; Notes of a Biology Watcher |url=https://archive.org/details/livesofcellnotes00thomrich |url-access=registration |publisher=Viking Press|location=New York |date=1974 |isbn=978-0-670-43442-8 }} |

{{Refend}} | {{Refend}} | ||

2021年2月8日 (一) 00:49的版本

盖亚假说 Gaia hypothesis(又称盖亚理论 Gaia theory或盖亚原理 Gaia principle)认为,生物体与地球上的无机环境相互作用,形成一个协同和自我调节的复杂系统,有助于维持和延续地球上的生命条件。

这个假设是由化学家詹姆斯·洛夫洛克 James Loveloc[1]提出的,[2]他以希腊神话中地球的化身盖亚的名字命名了这个想法。2006年,伦敦地质学会授予Lovelock沃拉斯顿勋章 Wollaston Medal,以表彰他在盖亚假说方面的工作。 [3]

与该假设有关的主题包括生物圈和生物体的进化如何影响全球温度的稳定性、海水的盐度、大气中的氧含量、液态水水圈的维持以及其他影响地球宜居性的环境变量。

盖亚假说最初被诟病为目的论、反对自然选择的原则,但后来的改进使盖亚假说与来自地球系统科学、生物地球化学和系统生态学等领域的观点相一致。.[4][5][6]Loveloc还曾经描述过地球的“地球物理学”。.[7]即便如此,盖亚假说仍然受到一些批评,今天许多科学家认为只有少数证据支持这一理论,或与现有的证据相矛盾。[8][9][10]

概述

盖亚假说认为,生物体与其环境共同进化。也就是说,生物“影响它们的非生物环境,而环境反过来又通过自然选择的过程影响生物群”。Lovelock(1995)在他的第二本书中提供了证据,展示了从早期嗜酸、产甲烷细菌的世界向今天支持更复杂生命的富氧大气的进化。

在《生物圈的定向进化: 生物地球化学选择还是盖亚? Directed Evolution of the Biosphere: Biogeochemical Selection or Gaia?》一书中,这一假说的简化版被称为“有影响力的盖亚 influential Gaia”[11]。安德烈·G·拉佩尼斯 Andrei G. Lapenis在这本书中指出生物影响着非生物世界的温度和大气等多个方面。这本书不是一个人的工作,而是一群俄罗斯科研人员的成果合并成这个通过同行评议的出版物。它通过“微观力量 micro-forces”[11]阐述了生命与环境的共同进化。

由于二十世纪苏联与西方国家存在隔阂,直到最近,在盖亚假说中引进重叠概念的早期苏联科学家才为西方科学界所熟知。[11] 这些科学家包括Piotr Alekseevich Kropotkin,Rafail Vasil'evich Rizpolozhensky,Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky和Vladimir Alexandrovich Kostitzin。

盖亚假说认为,地球是一个自我调节的复杂系统,包括生物圈、大气层、水圈和土壤圈,作为一个进化的系统紧密结合在一起。这个假说认为,这个被称为盖亚的系统作为整体,寻求适合当代生命的物理和化学环境。

生物学家和地球科学家通常将平衡一个时期的特征的因素视为系统的无方向涌现属性或有目的行为;例如,由于每个物种都追求自身利益,它们的联合行动可能对环境变化产生抵消作用。反对这一观点的人有时会举出一些导致了巨大变化而非平衡的事件作为反例,例如在太古宙 Archean末期和元古代 Proterozoic时期开始时,地球大气从还原环境 reducing environment转变为富含氧气。

盖亚通过一个由生物群无意识操作的控制论反馈系统实现进化,在完全的内稳态中广泛获得稳定的可居住条件。地球表面的许多过程对生命的保障条件至关重要,这些过程依赖于生命形式,特别是微生物与无机元素的相互作用。这些过程建立了一个全球控制系统,由地球系统的全球热力学不平衡状态提供动力,调节地球表面温度、大气成分和海洋盐度。

一种不太被接受的假说声称生物圈的变化是通过生物体的协调来实现的,并通过内稳态 Superorganism来维持这些条件。在一些版本的盖亚哲学 Gaia philosophy中,所有的生命形式都是一个被称为“盖亚”的生命行星的一部分。在这种观点下,大气、海洋和地壳将是盖亚通过生物多样性进行干预的结果。

以前在生物地球化学领域已经观察到受生命形式影响的行星内稳态的存在,而且地球系统科学等其他领域也在研究这一现象。盖亚假说的原创性依赖于这样一种观点: 即使地球或外部事件威胁到内稳态平衡,盖亚也会为了保持生命的最佳状态而积极追求这种平衡。

细节

盖亚假说假设地球是一个自我调节的复杂系统,包括生物圈、地球大气、水圈和土壤圈,作为一个进化系统紧密耦合。该假说认为,这个系统作为一个整体,称为盖亚,寻求一个最适合当代生活的物理和化学环境。[13]

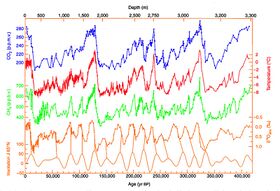

自从地球上有生命以来,太阳提供的能量增加了25%到30%;然而,地球表面温度一直保持在适宜居住的水平上,不曾突破上限或是下限。Lovelock还假设,产甲烷菌在早期大气中产生了较高水平的甲烷,这与在石化烟雾中发现的成分相似,在某些方面与土卫六上的大气相似。研究表明,在休伦期 Huronian、斯图尔特期 Sturtian和马里诺/瓦朗格冰期 Marinoan/Varanger Ice Ages,“氧冲击”和甲烷含量降低导致世界几乎变成了一个坚实的“雪球”。这些时代是前显生宙生物圈完全拥有自我调节能力的证据。

盖亚通过一个控制论反馈系统在生物群的无意识运作中实现进化,导致在完全的内稳态中广泛存在稳定的可居住条件。地球表面对生命条件至关重要的许多过程都依赖于生物,特别是微生物与无机元素的相互作用。这些过程建立了一个全球控制系统,调节地球的表面温度、大气组成和海洋盐度,其动力来自地球系统的全球热力学不平衡状态。[14]

温室气体CO2的处理在维持地球温度在可居住范围内起着关键作用(解释详见下文)。

受生命形式影响的行星内稳态的存在,以前在生物地球化学 biogeochemistry领域就已被观察到,而且其他领域,如地球系统科学也在研究这种稳态。盖亚假说的独创性依赖于这样一种观点,即盖亚积极追求这种内平衡,以保持维护生命的最佳状态,即使是在地球或外部事件威胁它们的时候。[15]

受盖亚假说的启发,CLAW 假说提出了一个在海洋生态系统和地球气候之间运行的反馈回路。该假说特别提出,产生二甲硫醚的浮游植物对气候变化有反应,这些反应导致了一个负反馈循环,稳定了地球大气的温度。

地球表面温度的调控

目前,人口的增加及其活动对环境的影响,例如温室气体的增加,可能导致环境中的负反馈成为正反馈。Lovelock表示,这可能会极大地加速全球变暖,但他后来又表示,这种影响也可能发生得更慢。

说明了在温室气体维持低于临界温度的过程中, CO2起着至关重要的作用。

有人批评盖亚假说似乎需要有机体之间不切实际的群体选择与合作,为了回应这种批评,James Lovelock 和 Andrew Watson建立了一个数学模型---- 雏菊世界 Daisyworld,其中生态竞争支撑着地。

受到盖亚假说启发的CLAW假说提出了一个在海洋生态系统和地球气候之间运行的反馈。[16] 假设具体提出,产生二甲基硫的特定浮游植物对气候作用力 climate forcing的变化作出反应,这些反应导致负反馈,从而稳定地球大气的温度。

雏菊世界调查了一个星球的能量预算,这个星球上生长着两种不同的植物,黑色雏菊和白色雏菊,这两种植物占据了星球表面的很大一部分。雏菊的颜色影响了地球的反照率,黑色的雏菊吸收更多的光线,使地球变暖,而白色的雏菊则反射更多的光线,使地球变冷。人们认为黑色雏菊在较低的温度下生长和繁殖最好,而白色雏菊则被认为在较高的温度下生长最好。当温度上升到接近白色雏菊所喜欢的温度时,白色雏菊繁殖率高于黑色雏菊,导致更大比例的白色表面,更多的阳光被反射,减少热量输入,最终使地球降温。相反,随着气温的下降,黑色雏菊繁殖率高于白色雏菊,吸收了更多的阳光,使地球变暖。因此,温度会收敛于两种植物繁殖率相等时对应温度的值。

目前,人口的增加及其活动对环境的影响,如温室气体的倍增,可能导致环境中的负反馈变成正反馈。Lovelock曾表示,这可能会带来一场盖亚的复仇[17]极度加速的全球变暖。[18]

Lovelock和Watson指出,在有限的条件下,如果太阳的能量输出发生变化,由于竞争产生的负反馈可以将地球温度稳定在支持生命存在的范围内,而没有生命的地球则会表现出巨大的温度波动。白色和黑色雏菊的百分比会不断变化,以保持植物繁殖率相等的温度值,使两种生命形式都能茁壮成长。

雏菊世界模拟

有人认为,这些结果是可以预测的,因为Lovelock和Watson选择的例子产生了他们想要的答案。

有人批评盖亚假说似乎需要有机体之间不切实际的群体选择和进化合作,詹姆斯·洛夫洛克 James Lovelock和安德鲁·沃森 Andrew Watson开发了一个数学模型——雏菊世界 Daisyworld,其中生态竞争为基础行星温度调节。 [19]

长期以来,海洋盐度一直保持在3.5% 左右。海洋环境中盐度的稳定性很重要,因为大多数细胞需要相当恒定的盐度,一般不能耐受超过5% 的盐度值。海洋盐度为何恒定是一个长期的奥秘,因为没有任何方法可以抵消来自河流的流入盐。最近有人提出,盐分也会洋中脊的热水喷口排出,因此盐度可能受到穿过炽热玄武岩的海水循环的强烈影响。然而,海水的组成离平衡还很远,如果没有有机过程的影响,很难解释这一事实。有一种解释认为,地球历史上盐滩的形成是盐度平衡的原因之一。据推测,这些盐滩是由细菌菌落产生的,它们在生命过程中固定离子和重金属。

盖亚假说认为,地球的大气组成是由于生命的存在而保持在动态稳定的状态。大气成分提供了支持现代生命的条件。大气中除惰性气体以外的所有大气气体,要么是由生物体产生的,要么是由生物体加工的。

地球大气层的稳定性不是化学平衡的结果。氧是一种活性化合物,最终会与地球大气层和地壳中的气体和矿物质结合。在大氧化事件开始之前,大约5000万年前,氧气才开始在大气中持续少量存在。自寒武纪以来,大气中氧浓度一直在大气体积的15% 至35% 之间波动。微量的甲烷(每年产生100,000吨)不适合存在,因为甲烷在氧气氛中是可燃的。

地球大气层中的干燥空气大致(按体积计算)含有78.09% 的氮气、20.95% 的氧气、0.93% 的氩气、0.039% 的二氧化碳以及少量的其他气体,包括甲烷。Lovelock最初推测,高于25% 的氧气浓度会增加森林大火和森林大火的发生频率。石炭纪和白垩纪煤系地质时期O2浓度确实超过了25%时,正是这一时期形成了火成木炭。这一结果支持了Lovelock 的论点。

Daisyworld研究了由两种不同类型的植物(黑色雏菊和白色雏菊)组成的行星的能量预算。这两种植物被认为占据了地表的很大一部分。雏菊的颜色影响着这个星球的反照率 albedo,因此黑色雏菊吸收更多的光并温暖地球,而白色雏菊则反射更多的光并使地球降温。黑雏菊在较低温度下生长繁殖最好,而白雏菊在较高温度下生长繁殖最好。当温度上升到接近白色雏菊的最适生长温度时,白色雏菊的繁殖能力超过了黑色雏菊,导致白色表面的比例增大,更多的阳光被反射,减少了热量输入,最终使地球变冷。相反,随着温度的下降,黑雏菊的繁殖能力超过了白雏菊,吸收了更多的阳光,使地球变暖。因此,温度将收敛到两种植物繁殖率相等对应的温度值。

Lovelock和Watson表明,在有限的条件范围内,如果太阳的能量输出发生变化,由于竞争而产生的负反馈可以将地球的温度稳定在支持生命的值上,而没有生命的行星则会出现大范围的温度波动。白雏菊和黑雏菊的比例会不断变化,以使温度保持在植物繁殖率相等的值,从而使两种生命形式都能茁壮成长。

盖亚假说的科学家们把生物体参与碳循环看作是维持适合生命条件的复杂过程之一。火山活动是大气中二氧化碳的最重要的自然来源,而碳酸盐岩的沉淀是大气中二氧化碳最重要的去除途径。碳沉淀、溶解和固定受到土壤中细菌和植物根系的影响,这些细菌和植物根系可以改善气体循环,或者在珊瑚礁中,碳酸钙以固体的形式沉积在海底。碳酸钙被活的有机体用来制造含碳的结构和外壳。一旦死亡,生物体的外壳就会沉到海底,在那里它们产生白垩和石灰石的沉淀物。

有人认为,结果是可预测的,因为Lovelock和Watson选择的例子产生了他们想要的反应。 [20]

其中一种是赫氏圆石藻,这是一种数量丰富的颗石藻类,也参与了云的形成。通过增加球石氟化物的寿命来补偿过量的CO2,增加了锁定在海底的CO2的数量。球石粉会增加云量,从而控制地表温度,有助于降低整个地球的温度,有利于地球上植物所必需的降水。近年来,大气中CO2浓度有所增加,有证据表明,海洋藻华的浓度也在增加。

海洋盐度调节

地衣和其他生物加速了岩石表面的风化,而岩石在土壤中的分解也加快了,这要归功于根、真菌、细菌和地下动物的活动。因此,二氧化碳从大气层流向土壤的过程是在生物的帮助下调节的。当大气中CO2水平升高时,温度升高,植物生长。这种生长会增加植物对二氧化碳的消耗,植物会将二氧化碳处理到土壤中,从大气中排出。

在很长一段时间内,海洋盐度一直保持在3.5%左右。[21]海洋环境中的盐度稳定性非常重要,因为大多数细胞需要相当恒定的盐度,并且通常不能耐受超过5%的盐度值。恒定的海洋盐度是一个长期存在的谜团,因为没有任何过程可以抵消河流中的盐流入。大洋中脊上的热水喷口会排出盐分,有人认为[22]这说明盐分也会受到海水循环的强烈影响。然而,海水的组成远未达到平衡,如果没有有机过程的影响,很难解释这一事实。地球历史中盐滩的形成是一个常用的证据。据推测,这些盐滩是由在生命过程中固定离子和重金属的菌落产生的。[21]

在地球的生物地球化学过程中,源和汇是元素的运动。我们海洋中盐离子的组成是:钠(Na+)、氯(Cl-)、硫酸盐(SO42-)、镁(Mg2+)、钙(Ca2+)和钾(K+)。构成盐度的元素不易变化,是海水的一种保守属性。[21]有许多机制可以将盐度从颗粒形态改变为溶解形态,然后再返回。已知的钠(即盐)因为岩石的风化、侵蚀和溶解作用被输送到河流中并沉积到海洋中。

地中海是盖亚的肾脏,由 KennethJ.Hsue在2001年发现的。地中海的“干涸”是肾功能正常的证据。早期的“肾功能”是在“白垩纪(南大西洋)、侏罗纪(墨西哥湾)、二叠纪-三叠纪(欧洲)、泥盆纪(加拿大)、寒武纪/前寒武纪(冈瓦纳)盐沼沉积时期进行的。” [23]

地球是一个完整的整体,一个有生命的存在,这个观念有着悠久的传统。神话中的盖亚是拟人化地球的原始希腊女神,是希腊版本的“自然母亲”。

大气层的氧气调节

派祖母 PIE grandmother,或地球母亲。 James Lovelock根据小说家威廉·戈尔丁 William Golding的建议给他的假设起了这个名字,他当时和Lovelock住在同一个村子里(英国威尔特郡鲍尔查尔克)。Golding的建议是以Gea为基础的,Gea是希腊女神名字的另一种拼写,在地质学、地球物理和地球化学中,Gea是前缀。后来,博物学家和探险家亚历山大·冯·洪堡 Alexander von Humboldt认识到生物、气候和地壳的共同进化。他的远见卓识的声明在西方没有被广泛接受,几十年后,盖亚假说刚提出时同样受到了科学界的抵制。

同样在20世纪之交,现代环境伦理学发展的先驱、荒野保护运动的先驱奥尔多 · 利奥波德在他的生物中心或整体的土地伦理学中提出了一个有生命的地球。

盖亚假说指出,地球的大气成分由于生命的存在而保持在动态稳定的状态。[24]大气中除惰性气体以外的所有大气气体都是由生物体制造或加工而成。

地球大气的稳定性不是化学平衡造成的。氧气是一种活性化合物,最终会与地球大气层和地壳上的气体和矿物质结合。在大氧化事件开始前的5000万年,氧气才在大气中少量存在。[25] 自寒武纪开始以来,大气氧浓度值一直在大气体积的15%到35%之间波动。甲烷的痕迹(每年产生10万吨)是不存在的,因为甲烷在氧气环境中是可燃的。

盖亚假说和环境运动的另一个影响来自于苏联和美利坚合众国之间太空竞赛。在20世纪60年代,第一批进入太空的人类可以看到地球作为一个整体的样子。1968年,宇航员威廉 · 安德斯在阿波罗8号任务期间拍摄的地出照片,通过总体效应成为全球生态运动的早期象征。

65年9月,Lovelock在加利福尼亚喷气推进实验室研究探测火星生命的方法时,开始定义由生物群落控制的自我调节地球的概念。第一篇提到它的论文是行星大气:与C.E.Giffin合著的与生命存在有关的成分和其他变化。一个主要的概念是,通过大气的化学成分可以在行星尺度上探测到生命。根据picdumidi天文台收集的数据,像火星或金星这样的行星,其大气层处于化学平衡状态。这种与地球大气的差异被认为是这些行星上没有生命的证据。

Lovelock在1972年和1974年的期刊文章中提出了盖亚假说,并在1979年出版了一本畅销书,名为《寻找盖亚 The Quest for Gaia》 ,开始引起科学界和批判界的关注。

Lovelock首先将其称为地球反馈假说,解释氧气和甲烷等化学物质在地球大气中如何保持稳定浓度。Lovelock认为,在其他行星的大气层中探测这种组合,是一种相对便宜可靠的探测生命的方法。

后来出现了其他关系,例如海洋生物产生的硫和碘的数量与陆地生物所需的数量大致相同,这些都支持了这一假说。

地球大气中的干空气大约(按体积)包含78.09%氮,20.95%的氧,0.93%氩,0.039%二氧化碳,以及少量其他气体,包括甲烷。Lovelock最初推测,氧气浓度超过25%会增加森林火灾和火灾的发生率。最近在石炭纪和白垩纪煤系中火成木炭的研究(这两个地质时期O2浓度超过25%)支持了Lovelock的观点。

1971年,微生物学家 Lynn Margulis博士加入了 Lovelock 的行列,努力将最初的假设充实为科学证明的概念。Margulis贡献了她关于微生物如何影响大气层和地球表面不同层次的知识。这位美国生物学家也唤受到科学界的批评,因为她倡导真核细胞器起源的理论,以及她对美国共生发源学会的贡献——现在被接受了Margulis在她的书《共生星球 The Symbiotic Planet》中将最后八章用于描述盖亚。然而,她反对对盖亚的广泛拟人化,并强调盖亚“不是一个有机体” ,而是“有机体之间相互作用的一个新兴属性”。她将盖亚定义为“组成地球表面一个巨大生态系统的一系列相互作用的生态系统”。这本书最令人难忘的“口号”实际上是由Margulis的一个学生打趣说的: “从太空看,盖亚只是共生而已。”

CO2处理

盖亚的科学家认为,生物参与碳循环是维持适宜生命条件的复杂过程之一。地球大气中的二氧化碳最重要的自然来源是火山活动,而最重要的去除过程是碳酸盐岩的沉淀,溶液和固碳受土壤中的细菌和植物根系的影响,它们改善了气体循环,珊瑚礁中碳酸钙以固体形式沉积在海底。碳酸钙被生物用来制造含碳结构和贝壳。一旦死亡,这些生物的壳就会落到海底,在那里它们会产生白垩和石灰岩的沉积物。

One of these organisms is Emiliania huxleyi, an abundant coccolithophore algae which also has a role in the formation of clouds.[26] CO2 excess is compensated by an increase of coccolithophoride life, increasing the amount of CO2 locked in the ocean floor. Coccolithophorides increase the cloud cover, hence control the surface temperature, help cool the whole planet and favor precipitations necessary for terrestrial plants.[citation needed] Lately the atmospheric CO2 concentration has increased and there is some evidence that concentrations of ocean algal blooms are also increasing.[27]

Lichen and other organisms accelerate the weathering of rocks in the surface, while the decomposition of rocks also happens faster in the soil, thanks to the activity of roots, fungi, bacteria and subterranean animals. The flow of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to the soil is therefore regulated with the help of living beings. When CO2 levels rise in the atmosphere the temperature increases and plants grow. This growth brings higher consumption of CO2 by the plants, who process it into the soil, removing it from the atmosphere.

历史

Lovelock谨慎地提出了盖亚假说的一个版本,这一版本中盖亚并不是有意地在她的环境中维持生命赖以生存的复杂平衡。看起来,盖亚假说“故意”行为的说法只是他那本广受欢迎的书中的一个比喻性陈述,并不是字面意义上的理解。这种对盖亚假说的新陈述更能为科学界所接受。在这次会议之后,大多数关于目的论的指责都停止了。

先例

In the eighteenth century, as geology consolidated as a modern science, James Hutton maintained that geological and biological processes are interlinked.[28] Later, the naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt recognized the coevolution of living organisms, climate, and Earth's crust.[28] In the twentieth century, Vladimir Vernadsky formulated a theory of Earth's development that is now one of the foundations of ecology. Vernadsky was a Ukrainian geochemist and was one of the first scientists to recognize that the oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere result from biological processes. During the 1920s he published works arguing that living organisms could reshape the planet as surely as any physical force. Vernadsky was a pioneer of the scientific bases for the environmental sciences.[29] His visionary pronouncements were not widely accepted in the West, and some decades later the Gaia hypothesis received the same type of initial resistance from the scientific community.

In the eighteenth century, as geology consolidated as a modern science, James Hutton maintained that geological and biological processes are interlinked.[34] Later, the naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt recognized the coevolution of living organisms, climate, and Earth's crust.[34] In the twentieth century, Vladimir Vernadsky formulated a theory of Earth's development that is now one of the foundations of ecology. Vernadsky was a Ukrainian geochemist and was one of the first scientists to recognize that the oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere result from biological processes. During the 1920s he published works arguing that living organisms could reshape the planet as surely as any physical force. Vernadsky was a pioneer of the scientific bases for the environmental sciences.[35] His visionary pronouncements were not widely accepted in the West, and some decades later the Gaia hypothesis received the same type of initial resistance from the scientific community.

Also in the turn to the 20th century Aldo Leopold, pioneer in the development of modern environmental ethics and in the movement for wilderness conservation, suggested a living Earth in his biocentric or holistic ethics regarding land.

- It is at least not impossible to regard the earth's parts—soil, mountains, rivers, atmosphere etc,—as organs or parts of organs of a coordinated whole, each part with its definite function. And if we could see this whole, as a whole, through a great period of time, we might perceive not only organs with coordinated functions, but possibly also that process of consumption as replacement which in biology we call metabolism, or growth. In such case we would have all the visible attributes of a living thing, which we do not realize to be such because it is too big, and its life processes too slow.

- — Stephan Harding, Animate Earth.[30]

盖亚假说和环境运动的另一个总体影响来自苏联和美利坚合众国之间太空竞赛的副作用。在20世纪60年代,第一批进入太空的人类可以看到地球的整体面貌。1968年宇航员William Anders在Apollo 8任务期间拍摄的照片“地球升起”,通过概述效果成为全球生态运动的早期标志。[31]

假说提出

Lovelock started defining the idea of a self-regulating Earth controlled by the community of living organisms in September 1965, while working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California on methods of detecting life on Mars.[32][33] The first paper to mention it was Planetary Atmospheres: Compositional and other Changes Associated with the Presence of Life, co-authored with C.E. Giffin.[34] A main concept was that life could be detected in a planetary scale by the chemical composition of the atmosphere. According to the data gathered by the Pic du Midi observatory, planets like Mars or Venus had atmospheres in chemical equilibrium. This difference with the Earth atmosphere was considered to be a proof that there was no life in these planets.

Lovelock formulated the Gaia Hypothesis in journal articles in 1972[1] and 1974,[2] followed by a popularizing 1979 book Gaia: A new look at life on Earth. An article in the New Scientist of February 6, 1975,[35] and a popular book length version of the hypothesis, published in 1979 as The Quest for Gaia, began to attract scientific and critical attention.

Lovelock called it first the Earth feedback hypothesis,[36] and it was a way to explain the fact that combinations of chemicals including oxygen and methane persist in stable concentrations in the atmosphere of the Earth. Lovelock suggested detecting such combinations in other planets' atmospheres as a relatively reliable and cheap way to detect life.

Later, other relationships such as sea creatures producing sulfur and iodine in approximately the same quantities as required by land creatures emerged and helped bolster the hypothesis.[37]

In 1971 microbiologist Dr. Lynn Margulis joined Lovelock in the effort of fleshing out the initial hypothesis into scientifically proven concepts, contributing her knowledge about how microbes affect the atmosphere and the different layers in the surface of the planet.[4] The American biologist had also awakened criticism from the scientific community with her advocacy of the theory on the origin of eukaryotic organelles and her contributions to the endosymbiotic theory, nowadays accepted. Margulis dedicated the last of eight chapters in her book, The Symbiotic Planet, to Gaia. However, she objected to the widespread personification of Gaia and stressed that Gaia is "not an organism", but "an emergent property of interaction among organisms". She defined Gaia as "the series of interacting ecosystems that compose a single huge ecosystem at the Earth's surface. Period". The book's most memorable "slogan" was actually quipped by a student of Margulis': "Gaia is just symbiosis as seen from space".

James Lovelock called his first proposal the Gaia hypothesis but has also used the term Gaia theory. Lovelock states that the initial formulation was based on observation, but still lacked a scientific explanation. The Gaia hypothesis has since been supported by a number of scientific experiments[38] and provided a number of useful predictions.[39] In fact, wider research proved the original hypothesis wrong, in the sense that it is not life alone but the whole Earth system that does the regulating.[13]

第一次盖亚会议

1985年,关于盖亚假说的第一次公开研讨会,“地球是一个活的有机体吗?”在马萨诸塞大学阿默斯特举行。[40] The principal sponsor was the National Audubon Society. Speakers included James Lovelock, George Wald, Mary Catherine Bateson, Lewis Thomas, John Todd, Donald Michael, Christopher Bird, Thomas Berry, David Abram, Michael Cohen, and William Fields. Some 500 people attended.[41]

第二次盖亚会议

1988年,climatology和Stephen Schneider组织了一次美国地球物理联合会会议。关于盖亚假说的第一次查普曼会议 。

在会议的“哲学基础”会议上,David Abram谈到了隐喻在科学中的影响,盖亚假说提供了一种新的、可能改变游戏规则的隐喻,而James Kirchner则批评盖亚假说的不精确性。Kirchner声称,Lovelock和Margulis提出的盖亚假说不是一个,而是四个-

- 共同进化的盖亚 Coevolution Gaia:生命和环境是以耦合的方式进化的。基什内尔声称,这已经被科学界接受,并不是什么新鲜事。

- 自我平衡的盖亚 Homeostatic Gaia:生命维持着自然环境的稳定,这种稳定性使生命得以继续存在。

- 地球物理盖亚 Geophysics Gaia:盖亚假说引起了人们对地球物理周期的兴趣,因此导致了地球物理动力学中有趣的新研究。

- 优化盖亚 Optimising Gaia:盖亚塑造了地球,使之成为整个生命的最佳环境。基什内尔声称,这是不可测试的,因此是不科学的。

Kirchner发现了两种选择“软弱的盖亚”断言,为了所有生命的繁衍,生命往往会使环境变得稳定根据基什内尔的说法,“强大的盖亚 Strong Gaia”断言,生命趋向于使环境稳定,“使”所有生命繁荣昌盛。基什内尔声称,强大的盖亚是不稳定的,因此不科学。 [42]

.

然而,Lovelock和其他支持盖亚假说的科学家,确实试图反驳这种说法,即这个假设是不科学的,因为不可能通过受控实验来检验它。例如,针对盖亚假说是目的论的指控,Lovelock和安德鲁·沃森提出了雏菊世界模型(及其修改作为反驳这些批评的证据。[19]Lovelock说,雏菊世界模型“证明了全球环境的自我调节可以通过不同方式改变当地环境的生活类型之间的竞争产生”。 [43]

Lovelock谨慎地提出了盖亚假说的一个版本,没有声称盖亚有意或有意识地维持着生命生存所需的复杂平衡。看来盖亚假说“故意”的行为是他最受欢迎的第一本书中的隐喻性陈述,并不是字面意思。盖亚假说的这一新说法更为科学界所接受。在这次会议之后,目的论的大多数指控都停止了。

第三次盖亚会议

到2000年6月23日在西班牙巴伦西亚举行的关于盖亚假说的第二届查普曼会议召开之时,[44]情况发生了很大变化。与其讨论Gaian目的论观点或Gaia假设的“类型”,不如说是将特定的机制维持在基本的长期动态平衡上,而该机制是在重大的进化长期结构变化的框架内保持的。

主要问题是:[45]

- “被称为盖亚的全球生物地球化学/气候系统是如何随时间变化的?它的历史是什么?盖亚能在一个时间尺度上保持系统的稳定性,但在较长的时间尺度上仍能经历向量变化吗?如何利用地质记录来检验这些问题?”

- “盖亚假说的结构是什么?反馈是否足够强烈,足以影响气候的演变?系统的某些部分是由任何给定时间正在进行的任何学科研究实际确定的,还是有一组应该被视为最真实的部分来理解盖亚假说,即随着时间的推移包含进化中的有机体?盖亚系统的这些不同部分之间的反馈是什么?物质的接近封闭对盖亚作为全球生态系统的结构和生命的生产力意味着什么?”

- “盖亚假说过程和现象的模型如何与现实联系起来,它们如何帮助解决和理解盖亚假说?雏菊世界的结果如何传递到真实世界?“雏菊”的主要候选对象是什么?我们是否找到雏菊对盖亚理论有意义吗?我们应该如何寻找雏菊,我们应该加强搜索?如何使用气候系统的过程模型或全球模型(包括生物群并允许化学循环)来研究盖亚机制?”

1997年,Tyler Volk认为,盖亚系统几乎不可避免地会产生,这是朝着使熵产量最大化的远非平衡的状态演化的结果,Kleidon(2004)同意这样的说法:“自稳行为可以从与行星反照率相关的MEP状态中产生”;“……生物地球在MEP状态下的行为很可能导致地球系统在长时间尺度上的近稳态行为,正如盖亚假说所述”。Staley(2002)同样提出了“……一种基于更传统的达尔文原理 Darwinian principles的盖亚理论的替代形式。在这种新方法中,环境调控是人口动态的结果,而不是达尔文选择 Darwinian selection。选择的作用是偏爱最能适应当前环境条件的有机体。然而,环境并不是进化的静态背景,而是受到生物存在的严重影响。由此产生的共同进化动态过程最终导致平衡和最优条件的收敛。

第四次盖亚会议

第四届盖亚假说国际会议于2006年10月在乔治梅森大学阿灵顿分校举行,会议由北弗吉尼亚州公园管理局和其他机构赞助。 [46]

NVRPA的首席自然学家Martin Ogle和长期以来的Gaia假设支持者组织了这次活动。Lynn Margulis是马萨诸塞州阿默斯特大学地球科学系的著名大学教授,长期以来一直倡导盖亚假说。其他发言人包括:纽约大学地球与环境科学计划的联合主任Tyler Volk;Donald Aitken Associates的负责人Donald Aitken博士;亨氏科学,经济与环境中心总裁Thomas Lovejoy博士;Robert Correll,美国气象学会大气政策计划高级研究员以及著名的环境伦理学家J. Baird Callicott。

这次会议将盖亚假说作为一种科学和隐喻来探讨,以此来理解我们如何着手解决21世纪的问题,如气候变化和持续的环境破坏

批评

最初很少受到科学家的关注(从1969年到1977年),此后的一段时间里,最初的盖亚假说受到了许多科学家的批评,比如Ford Doolittle,[47]Richard Dawkins[48]和Stephen Jay Gould。[49]Lovelock曾说过,因为他的假设是以希腊女神的名字命名的,[36]盖亚假说被许多非教派的科学家解释为新宗教 neo-Pagan religion。特别是许多科学家还批评了他的畅销书《盖亚》中采用的方法,认为地球上的生命是目的论的,认为事物是有目的的,是有目的的。Lovelock在1990年回应这一批评时说:“在我们的著作中我们没有任何地方表达行星自我调节是有目的的,或涉及生物群的远见或计划。”

Stephen Jay Gould批评盖亚假说是“一种隐喻,而不是一种机制。”[50]他想知道实现自我调节内稳态的实际机制。在为盖亚假说辩护时,大卫·艾布拉姆认为古尔德忽略了一个事实,即“机制”本身就是一个隐喻——尽管这是一个非常常见且常常未被人认识的隐喻——它使我们把自然和生命系统看作是从外部组织和建造的机器(而不是自动或自组织的)现象)。艾布拉姆认为,机械隐喻使我们忽视了生命实体的活动性或能动性,而盖亚假说的有机体隐喻强调了生物群和生物圈作为一个整体的能动性。[51][52]关于盖亚假说的因果关系,Lovelock认为没有单一的机制负责各种已知机制之间的联系可能永远不为人所知,这一点在其他生物学和生态学领域都是理所当然的,而具体的敌意是出于其他原因留给他自己的假设的。[53]

除了澄清自己的语言和对生命形式的理解之外,Lovelock自己将大部分批评归咎于批评家对非线性数学缺乏理解,以及贪婪还原论的线性化形式,在这种形式中,所有事件都必须在事实发生之前立即归因于特定的原因。他还指出,批评他的人大多是生物学家,但他的假设包括生物学以外领域的实验,有些自我调节的现象可能无法用数学解释。[53]

自然选择和进化

Lovelock提出,全球生物反馈机制可以通过自然选择而进化,他指出,为生存而改善环境的生物比那些破坏环境的生物做得更好。然而,在20世纪80年代早期,W. Ford Doolittle和Richard Dawkins分别反对盖亚假说的这一方面。Doolittle认为,单个生物体的基因组中没有任何东西能够提供Lovelock提出的反馈机制,因此盖亚假说没有提出任何合理的机制,是不科学的。[47]Dawkins同时指出,要使有机体协同行动,就需要有远见和计划,这与当前科学界对进化论的理解相悖。[48]和Doolittle一样,他也拒绝了反馈回路可以稳定系统的可能性。

Lynn Margulis,一位与Lovelock合作支持盖亚假说的微生物学家,在1999年指出,“Darwin的宏伟愿景没有错,只是不完整。Darwin(特别是他的追随者)强调个人之间对资源的直接竞争是主要的选择机制,他给人的印象是环境只是一个静态的竞技场”。她写道,地球大气、水圈和岩石圈的组成都是围绕着“设定点”来调节的,就像在体内平衡中一样,但是这些设定点会随着时间的推移而变化。[54]

进化生物学家W. D. Hamilton提出了盖亚哥白尼(Gaia Copernican)概念,并补充说将需要另一个牛顿来解释盖恩如何通过达尔文自然选择来进行自我调节。[55] 最近,Ford Doolittle建立在他和Inkpen的《ITSNTS》提案中提出,[56]差异性持久性可以与自然选择在进化中的差异性复制起相似的作用,从而提供自然选择理论与盖亚假设之间的可能和解。[57]

21世纪的批评

盖亚假说仍然受到科学界的广泛怀疑。例如,在2003年和2002年的《气候变化 Climatic Change》杂志上都提出了反对意见。反对它的一个重要论点是在许多例子中,生命对环境产生了有害或不稳定的影响,而不是采取行动来调节它。[8][9]最近几本书批评了盖亚假说,譬如“盖亚假说缺乏明确的观察支持,并且有重大的理论困难”[58]“(盖亚假说)令人不安地徘徊在污点、隐喻、事实和虚假科学之间,我宁愿把盖亚牢牢地放在原有的背景中”“盖亚假说既没有进化论的支持,也没有地质记录的经验证据的支持。”[59] CLAW假说[16]最初被认为是盖亚直接反馈的一个潜在例子,后来被发现对云的理解不那么可信凝聚核已经得到了改善。[60]2009年,美狄亚假说提出:生命对行星的状况非常有害,这与盖亚假说直接相反。[61]

2013年,托比·泰瑞尔 Toby Tyrrell在一本书中对盖亚假说总结道:“我认为盖亚假说是一条死胡同。然而,它的研究产生了许多新的和发人深省的问题。在拒绝盖亚假说的同时,我们也能欣赏到的独创性和广博的视野,认识到他大胆的概念有助于激发许多关于地球的新思想,并倡导一种研究地球的整体方法。”[62]在其他地方,他提出了自己的结论:“盖亚假说并不能精确地描述我们世界的运转机制。”[63] 这种说法需要被理解为是指盖亚假说的“强大”和“温和”形式,生物群遵循的原则是使地球处于最佳状态(强度5)或有利于生命(强度4),或者它作为一种内稳态机制(强度3)。后者是Lovelock所提倡的盖亚假说的“最弱”形式。泰瑞尔拒绝了。然而,他发现盖亚假说的两种较弱的形式:共同进化德盖亚假说和有影响力的盖亚假说,它们断言生命的进化和环境之间有密切的联系,生物学影响物理和化学环境,这两种说法都是可信的,但在这个意义上使用“盖亚假说”一词是没有用的,两种形式已经被自然选择和适应过程所接受和解释。[64]

参考文献

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 J. E. Lovelock (1972). "Gaia as seen through the atmosphere". Atmospheric Environment. 6 (8): 579–580. Bibcode:1972AtmEn...6..579L. doi:10.1016/0004-6981(72)90076-5.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lovelock, J.E.; Margulis, L. (1974). "Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the Gaia hypothesis". Tellus. Series A. Stockholm: International Meteorological Institute. 26 (1–2): 2–10. Bibcode:1974Tell...26....2L. doi:10.1111/j.2153-3490.1974.tb01946.x. ISSN 1600-0870.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ "Wollaston Award Lovelock". Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Turney, Jon (2003). Lovelock and Gaia: Signs of Life. UK: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-458-0. https://archive.org/details/lovelockgaiasign0000turn.

- ↑ Schwartzman, David (2002). Life, Temperature, and the Earth: The Self-Organizing Biosphere. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10213-1.

- ↑ Gribbin, John (1990), "Hothouse earth: The greenhouse effect and Gaia" (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

- ↑ Lovelock, James, (1995) "The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth" (W.W.Norton & Co)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kirchner, James W. (2002), "Toward a future for Gaia theory", Climatic Change, 52 (4): 391–408, doi:10.1023/a:1014237331082

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Volk, Tyler (2002), "The Gaia hypothesis: fact, theory, and wishful thinking", Climatic Change, 52 (4): 423–430, doi:10.1023/a:1014218227825

- ↑ Beerling, David (2007). The Emerald Planet: How plants changed Earth's history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280602-4. http://ukcatalogue.oup.com/product/9780192806024.do.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Lapenis, Andrei G. (2002). "Directed Evolution of the Biosphere: Biogeochemical Selection or Gaia?". The Professional Geographer. 54 (3): 379–391. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00337 – via [Peer Reviewed Journal].

- ↑ David Landis Barnhill, Roger S. Gottlieb (eds.), Deep Ecology and World Religions: New Essays on Sacred Ground, SUNY Press, 2010, p. 32.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, p. 255.

- ↑ Kleidon, Axel. How does the earth system generate and maintain thermodynamic disequilibrium and what does it imply for the future of the planet?. Article submitted to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society on Thu, 10 Mar 2011

- ↑ Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, p. 179.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Robert Jay Charlson; James Lovelock; Andreae, M. O.; Warren, S. G. (1987). "Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate". Nature. 326 (6114): 655–661. Bibcode:1987Natur.326..655C. doi:10.1038/326655a0.

- ↑ Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009,

- ↑ Lovelock J., NBC News. Link Published 23 April 2012, accessed 22 August 2012.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Watson, A.J.; Lovelock, J.E (1983). "Biological homeostasis of the global environment: the parable of Daisyworld". Tellus. 35B (4): 286–9. Bibcode:1983TellB..35..284W. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0889.1983.tb00031.x.

- ↑ Kirchner, James W. (2003). "The Gaia Hypothesis: Conjectures and Refutations". Climatic Change. 58 (1–2): 21–45. doi:10.1023/A:1023494111532.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Segar, Douglas (2012). The Introduction to Ocean Sciences. http://www.reefimages.com/oceans/SegarOcean3Chap05.pdf: Library of Congress. pp. Chapter 5 3rd Edition. ISBN 978-0-9857859-0-1.

- ↑ Gorham, Eville (1 January 1991). "Biogeochemistry: its origins and development". Biogeochemistry. Kluwer Academic. 13 (3): 199–239. doi:10.1007/BF00002942. ISSN 1573-515X.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ http://www.webviva.com, Justino Martinez. Web Viva 2007. "Scientia Marina: List of Issues". scimar.icm.csic.es (in English). Retrieved 2017-02-04.

{{cite web}}: External link in|last= - ↑ Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, p. 163.

- ↑ Anbar, A.; Duan, Y.; Lyons, T.; Arnold, G.; Kendall, B.; Creaser, R.; Kaufman, A.; Gordon, G.; Scott, C.; Garvin, J.; Buick, R. (2007). "A whiff of oxygen before the great oxidation event?". Science. 317 (5846): 1903–1906. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1903A. doi:10.1126/science.1140325. PMID 17901330.

- ↑ Harding, Stephan (2006). Animate Earth. Chelsea Green Publishing. pp. 65. ISBN 978-1-933392-29-5.

- ↑ "Interagency Report Says Harmful Algal Blooms Increasing". 12 September 2007. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Capra, Fritjof (1996). The web of life: a new scientific understanding of living systems. Garden City, N.Y: Anchor Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-385-47675-1. https://archive.org/details/weboflifenewscie00capr/page/23.

- ↑ S.R. Weart, 2003, The Discovery of Global Warming, Cambridge, Harvard Press

- ↑ Harding, Stephan. Animate Earth Science, Intuition and Gaia. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2006, p. 44.

- ↑ 100 Photographs that Changed the World by Life - The Digital Journalist

- ↑ Lovelock, J.E. (1965). "A physical basis for life detection experiments". Nature. 207 (7): 568–570. Bibcode:1965Natur.207..568L. doi:10.1038/207568a0. PMID 5883628.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ "Geophysiology". Archived from the original on 2007-05-06. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ↑ Lovelock, J.E.; Giffin, C.E. (1969). "Planetary Atmospheres: Compositional and other changes associated with the presence of Life". Advances in the Astronautical Sciences. 25: 179–193. ISBN 978-0-87703-028-7.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ Lovelock, John and Sidney Epton, (February 8, 1975). "The quest for Gaia". New Scientist, p. 304.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Harding, Stephan. Animate Earth Science, Intuition and Gaia. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2006, p. 44. ISBN 1-933392-29-0

- ↑ Hamilton, W.D.; Lenton, T.M. (1998). "Spora and Gaia: how microbes fly with their clouds". Ethology Ecology & Evolution. 10 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/08927014.1998.9522867. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-23.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ J. E. Lovelock (1990). "Hands up for the Gaia hypothesis". Nature. 344 (6262): 100–2. Bibcode:1990Natur.344..100L. doi:10.1038/344100a0.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ Volk, Tyler (2003). Gaia's Body: Toward a Physiology of Earth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-72042-7.

- ↑ Joseph, Lawrence E. (November 23, 1986). "Britain's Whole Earth Guru". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ Bunyard, Peter (1996), "Gaia in Action: Science of the Living Earth" (Floris Books)

- ↑ Kirchner, James W. (1989). "The Gaia hypothesis: Can it be tested?". Reviews of Geophysics. 27 (2): 223. Bibcode:1989RvGeo..27..223K. doi:10.1029/RG027i002p00223.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ Lenton, TM; Lovelock, JE (2000). "Daisyworld is Darwinian: Constraints on adaptation are important for planetary self-regulation". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 206 (1): 109–14. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2000.2105. PMID 10968941.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ Simón, Federico (21 June 2000). "GEOLOGÍA Enfoque multidisciplinar La hipótesis Gaia madura en Valencia con los últimos avances científicos". El País (in spanish). Retrieved 1 December 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ American Geophysical Union. "General Information Chapman Conference on the Gaia Hypothesis University of Valencia Valencia, Spain June 19-23, 2000 (Monday through Friday)". AGU Meetings. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ↑ Official Site of Arlington County Virginia. "Gaia Theory Conference at George Mason University Law School". Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Doolittle, W. F. (1981). "Is Nature Really Motherly". The Coevolution Quarterly. Spring: 58–63.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Dawkins, Richard (1982). The Extended Phenotype: the Long Reach of the Gene. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286088-0.

- ↑ Turney, Jon. "Lovelock and Gaia: Signs of Life" (Revolutions in Science)

- ↑ Gould S.J. (June 1997). "Kropotkin was no crackpot". Natural History. 106: 12–21.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ↑ Abram, D. (1988) "The Mechanical and the Organic: On the Impact of Metaphor in Science" in Scientists on Gaia, edited by Stephen Schneider and Penelope Boston, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1991

- ↑ "The Mechanical and the Organic". Archived from the original on February 23, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Lovelock, James (2001), Homage to Gaia: The Life of an Independent Scientist (Oxford University Press)

- ↑ Margulis, Lynn. Symbiotic Planet: A New Look At Evolution. Houston: Basic Book 1999

- ↑ Lovelock, James. The Vanishing Face of Gaia. Basic Books, 2009, pp. 195-197.

- ↑ Doolittle WF, Inkpen SA. Processes and patterns of interaction as units of selection: An introduction to ITSNTS thinking. PNAS April 17, 2018 115 (16) 4006-4014

- ↑ Doolittle WF. Darwinizing Gaia. Journal of Theoretical BiologyVolume 434, 7 December 2017, Pages 11-19

- ↑ Waltham, David (2014). Lucky Planet: Why Earth is Exceptional – and What that Means for Life in the Universe. Icon Books. ISBN 9781848316560. https://archive.org/details/luckyplanetwhyea0000walt.

- ↑ Cockell, Charles; Corfield, Richard; Dise, Nancy; Edwards, Neil; Harris, Nigel (2008). An Introduction to the Earth-Life System. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521729536. http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/earth-and-environmental-science/palaeontology-and-life-history/introduction-earth-life-system.

- ↑ Quinn, P.K.; Bates, T.S. (2011), "The case against climate regulation via oceanic phytoplankton sulphur emissions", Nature, 480 (7375): 51–56, Bibcode:2011Natur.480...51Q, doi:10.1038/nature10580, PMID 22129724

- ↑ Peter Ward (2009), The Medea Hypothesis: Is Life on Earth Ultimately Self-Destructive?

- ↑ Tyrrell, Toby (2013), On Gaia: A Critical洛夫洛克 Investigation of the Relationship between Life and Earth, Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 209, ISBN 9780691121581

- ↑ Tyrrell, Toby (26 October 2013), "Gaia: the verdict is…", New Scientist, 220 (2940): 30–31, doi:10.1016/s0262-4079(13)62532-4

- ↑ Tyrrell, Toby (2013), On Gaia: A Critical Investigation of the Relationship between Life and Earth, Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 208, ISBN 9780691121581

- Bondì, Roberto (2006). Blu come un'arancia. Gaia tra mito e scienza. Torino, Utet: Prefazione di Enrico Bellone. ISBN 978-88-02-07259-3.

- Bondì, Roberto (2007). Solo l'atomo ci può salvare. L'ambientalismo nuclearista di James Lovelock. Torino, Utet: Prefazione di Enrico Bellone. ISBN 978-88-02-07704-8.

- Jaworski, Helan (1928). Le Géon ou la Terre vivante. Paris: Librairie Gallimard.

- Lovelock, James. The Independent. The Earth is about to catch a morbid fever, 16 January 2006.

- Kleidon, Axel (2004). "Beyond Gaia: Thermodynamics of Life and Earth system functioning". Climatic Change. 66 (3): 271–319. doi:10.1023/B:CLIM.0000044616.34867.ec.

- Lovelock, James (1995). The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31239-3.

- Lovelock, James (2000). Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286218-1.

- Lovelock, James (2001). Homage to Gaia: The Life of an Independent Scientist. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860429-7. https://archive.org/details/homagetogaialife0000love.

- Lovelock, James (2006), interviewed in How to think about science, CBC Ideas (radio program), broadcast January 3, 2008. Link

- Lovelock, James (2007). The Revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth Is Fighting Back — and How We Can Still Save Humanity. Santa Barbara CA: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9914-3.

- Lovelock, James (2009). The Vanishing Face of Gaia: A Final Warning. New York, NY: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01549-8.

- Margulis, Lynn (1998). Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-81740-6.

- Marshall, Alan (2002). The Unity of Nature: Wholeness and Disintegration in Ecology and Science. River Edge, N.J: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-86094-330-0.

- Staley M (September 2002). "Darwinian selection leads to Gaia". J. Theor. Biol. 218 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2002.3059. PMID 12297068.

- Schneider, Stephen Henry (2004). Scientists debate Gaia: the next century. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-19498-3.

- Thomas, Lewis G. (1974). The Lives of a Cell; Notes of a Biology Watcher. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-43442-8. https://archive.org/details/livesofcellnotes00thomrich.

进一步阅读

- Joseph, Lawrence E. (1990). Gaia: The Growth of an Idea. New York, N.Y.: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-31-204318-6. https://archive.org/details/gaia00lawr.

本中文词条由Henry翻译,三奇审校,薄荷欢迎在讨论页面留言。

本词条内容源自公开资料,遵守 CC3.0协议。

- CS1 errors: invalid parameter value

- CS1 errors: external links

- CS1 English-language sources (en)

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- CS1: long volume value

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2015

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- 控制论

- 生态学理论

- 气候变化反馈

- 生物地球化学

- 地球

- 生物学假说

- 天文学假设

- 气象假说