“马尔科夫链的粗粒化”的版本间的差异

| 第134行: | 第134行: | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\begin{aligned} | \begin{aligned} | ||

| − | p_{s_k A_j} = \sum_{s_m \in A_j} p_{s_k s_m} = p_{A_i A_j}, k \in A_i | + | p_{s_k A_j} = \frac{1}{|A_j|} \sum_{s_m \in A_j} p_{s_k s_m} = p_{A_i A_j}, k \in A_i |

\end{aligned} | \end{aligned} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| 第176行: | 第176行: | ||

#Hard Partitioning,即存在分组矩阵<math>V_{i, j} = 1\ if\ s_i \in s_j'\ and\ 0\ otherwise</math>; | #Hard Partitioning,即存在分组矩阵<math>V_{i, j} = 1\ if\ s_i \in s_j'\ and\ 0\ otherwise</math>; | ||

#<math>V</math>是一个lumpable分组。 | #<math>V</math>是一个lumpable分组。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Lumpable正例和反例== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 既然hard partition里有lumpable和non-lumpable分组,这里用一个简单的例子提供正例和反例。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 我们用到的是这样一个转移矩阵: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \begin{aligned} | ||

| + | P = P_{s_i s_j} = \left [ | ||

| + | \begin{array}{ccc:c} | ||

| + | 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.1 \\ | ||

| + | 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.1 \\ | ||

| + | 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.1 \\ | ||

| + | \hdashline0.1 & 0.1 & 0.1 & 0.7 | ||

| + | \end{array} | ||

| + | \right ] | ||

| + | \end{aligned} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====正例==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 我们可以看到,123行都是一样的,所以把他们分在一组,并把状态4分在另外一组,看起来像是一个合理的正例。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 接下来我们来计算一下。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 第1组的状态1到第1组的状态2,<math>p_{s_1 A_1} = p_{A_1 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_1} p_{s_1 s_m} = p_{s_1 s_1} + p_{s_1 s_2} + p_{s_1 s_3} = 0.3 \times 3 = 0.9 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 第1组的状态1到第2组的状态4,<math>p_{s_1 A_2} = p_{A_1 A_2} = \sum_{s_m \in A_2} p_{s_1 s_m} = p_{s_1 s_4} = 0.1 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 第2组的状态4到第1组的状态1,<math>p_{s_4 A_1} = p_{A_2 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_1} p_{s_4 s_m} = p_{s_4 s_1} + p_{s_4 s_2} + p_{s_4 s_3} = 0.1 \times 3 = 0.3 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 第2组的状态4到第2组的状态4,<math>p_{s_4 A_2} = p_{A_2 A_2} = \sum_{s_m \in A_2} p_{s_4 s_m} = p_{s_4 s_4} = 0.7 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \begin{aligned} | ||

| + | P = P_{A_k A_l} = \left [ | ||

| + | \begin{array}{c:c} | ||

| + | 0.9 & 0.1 \\ | ||

| + | \hdashline0.3 & 0.7 | ||

| + | \end{array} | ||

| + | \right ] | ||

| + | \end{aligned} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ====反例==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 现在我们来看一个反例:把状态12分为一组,状态34分为另一组, | ||

| + | |||

| + | 同样的,我们来计算一下。这次我们需要对3和4分开计算了。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 第1组的状态1到第1组的状态2,<math>p_{s_1 A_1} = p_{A_1 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_1} p_{s_1 s_m} = p_{s_1 s_1} + p_{s_1 s_2} = 0.3 \times 2 = 0.6 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 第1组的状态1到第2组的状态3,<math>p_{s_1 A_2} = p_{A_1 A_2} = \sum_{s_m \in A_2} p_{s_1 s_m} = p_{s_1 s_3} + p_{s_1 s_4} = 0.4 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 第2组的状态3到第1组的状态1,<math>p_{s_3 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_1} p_{s_4 s_m} = p_{s_3 s_1} + p_{s_3 s_2} = 0.3 \times 2 = 0.6 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 第2组的状态4到第1组的状态1,<math>p_{s_4 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_2} p_{s_4 s_m} = p_{s_4 s_1} + p_{s_4 s_2} = 0.1 \times 2 = 0.2 </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 这里我们就能看到,<math>p_{s_3 A_1} \neq p_{s_4 A_1}</math>,当同一组的两个状态<math>s_3</math>和<math>s_4</math>对其他组的转移概率不一样的话,如果我们强行按照这样来分组(也没办法强行,因为我们不知道<math>p_{A_2 A_1} = p_{s_3 A_1}</math>还是<math>p_{A_2 A_1} = p_{s_4 A_1}</math>),假设<math>p_{A_2 A_1} = 0.6</math>,我们会发现这样的粗粒化结果违背了一开始的定义,即粗粒化后的'''转移概率对所有的初始微观状态<math>\pi</math>都适用'''。因为当<math>\pi = s_4</math>的时候,<math>p_{A_2 A_1} = 0.6</math>这个转移概率就是错的,即使<math>\pi \neq s_4</math>,任何初始微观状态都会在某时刻达到<math>s_4</math>并导致转移概率出错。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ====一个更复杂的正例==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 这个三个相同状态的例子可能稍微有点简单,接下来我们来看一个稍微复杂一点的例子: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \begin{aligned} | ||

| + | P = P_{s_i s_j} = \left [ | ||

| + | \begin{array}{cc:cc} | ||

| + | 0.2 & 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.1 \\ | ||

| + | 0.4 & 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 \\ | ||

| + | \hdashline0.2 & 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.5 \\ | ||

| + | 0.1 & 0.2 & 0 & 0.7 | ||

| + | \end{array} | ||

| + | \right ] | ||

| + | \end{aligned} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | 对于这个马尔科夫矩阵,<math>\{\{1,2\}, \{3,4\}\}</math>是一个lumpable的分组。分组后的转移矩阵为: | ||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \begin{aligned} | ||

| + | P = P_{A_k A_l} = \left [ | ||

| + | \begin{array}{c:c} | ||

| + | 0.6 & 0.4 \\ | ||

| + | \hdashline0.3 & 0.7 | ||

| + | \end{array} | ||

| + | \right ] | ||

| + | \end{aligned} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

===基于Lumpability的粗粒化方法=== | ===基于Lumpability的粗粒化方法=== | ||

| 第181行: | 第277行: | ||

[[文件:Lump fig1.png|缩略图|398x398像素|图2:Zhang<ref name=":0" /> 文章中的示意图。图中左面四个矩阵都是lumpable马尔科夫矩阵,而右面的P_2是一个噪声矩阵,(P_1)^T P_2 = 0|替代=]] | [[文件:Lump fig1.png|缩略图|398x398像素|图2:Zhang<ref name=":0" /> 文章中的示意图。图中左面四个矩阵都是lumpable马尔科夫矩阵,而右面的P_2是一个噪声矩阵,(P_1)^T P_2 = 0|替代=]] | ||

| − | 由上面的lumpability公式(3) | + | 由上面的lumpability公式(3)和例子中我们能获得一个直观上的说法:当马尔科夫矩阵存在block结构,或者状态明显可被分成几类的时候,根据这样的partition,该矩阵就会lumpable,如图2中的<math>\bar{P}</math>所示,把相同的状态(行向量)分成一类的partition显然lumpable。 |

但是,有时候有些lumpable的矩阵的状态排序被打乱了(如图一中的<math>P_1</math>),或者矩阵包含了如<math>P_2</math>的噪声(如图2中的<math>P</math>,<math>P = P_1 + P_2</math>,<math>P_1^TP_2 = 0</math>)。 | 但是,有时候有些lumpable的矩阵的状态排序被打乱了(如图一中的<math>P_1</math>),或者矩阵包含了如<math>P_2</math>的噪声(如图2中的<math>P</math>,<math>P = P_1 + P_2</math>,<math>P_1^TP_2 = 0</math>)。 | ||

2024年9月18日 (三) 16:41的版本

马尔科夫矩阵是指满足每一行和为1的条件的方阵,而马尔科夫链指的是一个n维的状态的序列[math]\displaystyle{ x_t\ = \{1, ..., n\}_{t} }[/math],每一步的状态转换都有马尔科夫矩阵[math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]决定,即[math]\displaystyle{ x_{t+1} = x_t P }[/math]。

[math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]的每一行对应的每个状态转移到其他状态的概率。比如当[math]\displaystyle{ x_t }[/math]等于第一个状态的时候,[math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]的第一行展示了[math]\displaystyle{ x_{t+1} }[/math]状态的概率。

对马尔科夫链做粗粒化做粗粒化的意义是什么呢?我们看到文献中着重强调这两点:

- 我们在研究一个超大的系统的时候,比如复杂城市系统时,并不会关注每一个微观的状态的变化,在粗粒化中我们希望能过滤掉一些我们不感兴趣的噪声和异质性,而从中微观尺度中总结一些中尺度或宏观尺度的规律;

- 有些状态的转移概率非常相似,所以可以被看成同一类状态,对这种马尔科夫链做partitioning可以减少系统表示的冗余性;

- 在用到马尔科夫决策过程的强化学习里,对马尔科夫链做粗粒化可以减少状态空间的大小,提高训练效率。

粗粒化

马尔科夫链不只是一个马尔科夫矩阵那么简单,还涉及到了不同的状态,也会有状态之间的转移概率,所以我们可以从不同的角度来看待粗粒化:

- 对马尔科夫矩阵做粗粒化:在看待一个方阵时,我们可以把它想象成一个网络的邻接矩阵。节点为状态,连边为状态转移概率,状态转移的过程为一个粒子在节点间跳转,而粗粒化则是对这个网络做降维。

- 对状态空间做粗粒化:我们这里讨论的是离散状态的马尔科夫链,状态空间的大小等于马尔科夫链的大小。粗粒化可以看作对状态空间做分组并投影到新的状态空间。

- 对概率空间做粗粒化:从概率论出发,把状态的发生看作事件,通过计算事件发生的频率来构建概率空间。在降维表达事件的同时也构建了新的概率空间。

这三种出发点看似互有联系,但是具体关心的东西不同。第一种关注状态之间的连边拓扑结构,第二种关注不同状态的历史分布和相似性,第三种关注如何降维表达整个系统中的事件概率分布。

对马尔科夫链做粗粒化并没有一个统一的定义,目前该题目也没有一个完整的文献综述。在许多文献中,粗粒化coarse-graining和降维dimension reduction是重叠等价的。

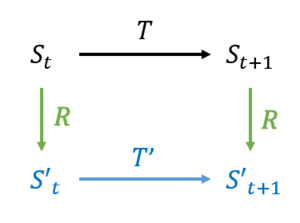

多数文献中会出现如图一的定义[1]:

对状态空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]和转移函数[math]\displaystyle{ T(t):S \rightarrow S }[/math],我们需要一个投影矩阵[math]\displaystyle{ R:S \rightarrow S' }[/math],和一个新的转移函数[math]\displaystyle{ T'(t):S' \rightarrow S' }[/math],而且[math]\displaystyle{ S' }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ T' }[/math]要符合马尔科夫链定义。

所以,我们能看出[math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math]是一个对状态空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]的降维函数(得到[math]\displaystyle{ S' }[/math])。而且,我们还需要把[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]降维成[math]\displaystyle{ T' }[/math]。如果[math]\displaystyle{ T:s_{t+1} = s_{t} P }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]为离散马尔科夫矩阵的话,这个针对马尔科夫矩阵的降维可以表示为

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{aligned} P' = W P V, \end{aligned} }[/math]

(1)

其中[math]\displaystyle{ P \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n} }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ P' \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times k} }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ W \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times n} }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ V \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times k} }[/math]。Buchholz[2]的文章中把[math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math]称作distributor matrix,而[math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]称作collector matrix。

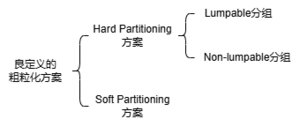

马尔科夫链的粗粒化可以分成Hard partitioning和Soft partitioning。Hard partitioning是指把若干个微观状态分成一个宏观状态类,且一个微观状态不能同时属于多个宏观状态类,而Soft partitioning则会有可能出现一个微观状态被分在属于多个宏观类的情况。

在Hard partitioning的情况下,[math]\displaystyle{ V_{i, j} = 1\ if\ s_i \in s_j'\ and\ 0\ otherwise }[/math][2],即一个表示[math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]属于[math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]列的零一分组矩阵,如果是Soft partitioning的话,[math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]则不一定会是零一矩阵。

而

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{aligned} W = D^{-1}(V)^T, D = diag(\alpha V), \end{aligned} }[/math]

(2)

其中[math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math]是一个非负对角矩阵。

所以,我们能看到,对马尔科夫链做粗粒化的时候,不仅要对状态空间做降维([math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math]),还要对马尔科夫矩阵都要做降维([math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]),当中也包含了对概率空间的降维([math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math])。

而且,有资料中还提到了粗粒化的交换律commutative[1]。按照上面的定义,[math]\displaystyle{ s_t }[/math]有两个路径能达到[math]\displaystyle{ s_{t+1}' }[/math]:

- 先得到下一步的[math]\displaystyle{ s_{t+1} = s_{t} P }[/math],再做粗粒化得到[math]\displaystyle{ s_{t+1}' = R(s_{t+1}) }[/math]

- 先做粗粒化得到[math]\displaystyle{ s_{t}' = R(s_{t}) }[/math],再得到下一步的[math]\displaystyle{ s_{t+1}' = s_{t}' P' }[/math]

而交换律则要求从这两条路径得到的结果应该是一样的,即[math]\displaystyle{ R(s_{t} P) = R(s_{t}) P' }[/math]。

因此,根据目前有迹可循的对马尔科夫链的粗粒化的定义来说,我们要求一个良定义的粗粒化方法上述提到过的两个规则:

- 粗粒化后的[math]\displaystyle{ S' }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ T' }[/math]要符合马尔科夫链定义。

- 满足交换律

但是注意,这是我们从不同来源[1]中总结出来的规则。目前我们还没找到一个严格的完备的定义。

而且,这只是最简单,最基本的对马尔科夫链的粗粒化,我们下面会介绍不同的指标,在上述的两个规则之上添加更多的规则会得出基于这些指标的粗粒化的方法。

在这个词条里,我们主要讨论Hard partitioning,主要参考的是Anru Zhang和Mengdi Wang的Spectral State Compression of Markov Processes[3],对Soft state aggregation感兴趣的朋友可以自行参阅S. P. Singh, T. Jaakkola, and M. I. Jordan, “Reinforcement learning with soft state aggregation."[4]

Rank

首先讨论的是一个马尔科夫矩阵的rank秩。

大家理解的线代里的rank秩的定义是看矩阵中的线性无关的行向量的数量,但是这里对秩的理解是从一种类似于信道的概念。

秩的定义为我们能找到的一组概率密度函数 [math]\displaystyle{ f_1, ... , f_r, g_1, ... , g_r }[/math],使得r在下列公式里最小:

[math]\displaystyle{ P(X_{t+1} | X_{t}) = \sum^r_{k=1} f_k(X_t) g_k(X_{t+1}) }[/math]

这里的秩的意思是,我们能多大程度上压缩信道,使得信息在宽度为秩的信道中无损传递。(笔者个人理解)

在n个离散状态的马尔科夫矩阵中,[math]\displaystyle{ f_1, ... , f_r, g_1, ... , g_r }[/math] 是维度为n的矩阵。

而我们能定义r × r的markov kernel [math]\displaystyle{ C = \{C_{ij} = \sum_{k=1}^n f_j(k)g_i(k)\} }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ f_1, ... , f_r }[/math] 为 left Markov features,[math]\displaystyle{ g_1, . . . , g_r }[/math] 为 right Markov features.

这个定义可以想象成可压缩的程度,也会是下面的hard partitioning的分组的数量。

Lumpability

Lumpability是一种对分类的衡量,笔者暂时还没找到一个正式的中文翻译。

这个概念最早出现在Kemeny, Snell在1969年的Finite Markov Chains[5]中。书中的定义是这样的:

给定一个state partition [math]\displaystyle{ A=\{A_1, A_2, ... ,A_r\} }[/math],我们能够用下列公式描述一个粗粒化后的马尔科夫链(lumped process),且这个转移概率对任何初始状态(starting vector) [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] 都是一样的:

[math]\displaystyle{

\begin{aligned}

&Pr_{\pi}[f_0 \in A_i] \\

&Pr_{\pi}[f_1 \in A_j | f_0 \in A_i] \\

&Pr_{\pi}[f_n \in A_t |f_{n-1} \in A_s, f_1 \in A_j, f_0 \in A_i]

\end{aligned}

}[/math]

作者提出了判断一个马尔科夫链对给定partition [math]\displaystyle{ A=\{A_1, A_2, ... ,A_r\} }[/math] 是否lumpable的充分必要条件为:

对于任意一对[math]\displaystyle{ A_i, A_j }[/math],每一个属于[math]\displaystyle{ A_i }[/math]的状态[math]\displaystyle{ s_k }[/math]的[math]\displaystyle{ p_{kA_j} }[/math]都是一样的。

也就是说

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{aligned} p_{s_k A_j} = \frac{1}{|A_j|} \sum_{s_m \in A_j} p_{s_k s_m} = p_{A_i A_j}, k \in A_i \end{aligned} }[/math]

(3)

这个公式表达的是,群组[math]\displaystyle{ A_i }[/math]到群组[math]\displaystyle{ A_j }[/math]的转移概率 = 群组[math]\displaystyle{ A_i }[/math]中任意状态[math]\displaystyle{ s_k }[/math]到群组[math]\displaystyle{ A_j }[/math]的转移概率 = 群组[math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]中任意状态[math]\displaystyle{ s_k }[/math]到群组[math]\displaystyle{ A_j }[/math]中的状态的转移概率的和。

请注意:lumpability有一个非常重要的前提,即我们要给定一个对马尔科夫链的state的partition,然后根据马尔科夫状态转移矩阵来决定这个partition对这个马尔科夫链是否lumpable。

所以,lumpability并不是一个马尔科夫链的特质,而是对马尔科夫链的某个state partition的特质。我们不能直接说某个马尔科夫链是lumpable或non-lumpable,但是我们可以说,对于某个马尔科夫链的某几个状态partition是lumpable或non-lumpable。

Lumpability和粗粒化

我们在粗粒化的部分提到了,马尔科夫链的粗粒化不仅要对状态空间做,也要对转移矩阵和概率空间做。

这三个部分可以同时做,也可以看作为:先对状态空间做,再对转移矩阵和概率空间做;即先对状态做分组,然后再获取对应的粗粒化后的转移矩阵。

我们也提到过对状态空间做粗粒化有Hard Partitioning和Soft Partitioning两种。Soft Partitioning可以看作把微观状态打散重构成了一些宏观状态,而Hard Partitioning则是更严格的,把若干个微观状态分成一个组。

而Lumpability就是一个指标,用来评价‘对于某一种Hard Partitioning的微观状态分组分案,是否对微观状态转移矩阵lumpable’。

不管状态空间按照哪一个Hard Partitioning方案做分类,它都有对应后续的对转移矩阵和概率空间的粗粒化方案(公式(1)和(2))[2],并满足上面提到的粗粒化的两个规则。

但是,其中的某些分组方案lumpable,也有某些分组方案non-lumpable。

所以,整个链条应该是这样的:

所以,一个满足lumpability的良定义的粗粒化方案应该在原来的两个条件下,再多加两个条件:

- 粗粒化后的[math]\displaystyle{ S' }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ T' }[/math]要符合马尔科夫链定义;

- 满足交换律;

- Hard Partitioning,即存在分组矩阵[math]\displaystyle{ V_{i, j} = 1\ if\ s_i \in s_j'\ and\ 0\ otherwise }[/math];

- [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]是一个lumpable分组。

Lumpable正例和反例

既然hard partition里有lumpable和non-lumpable分组,这里用一个简单的例子提供正例和反例。

我们用到的是这样一个转移矩阵:

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{aligned} P = P_{s_i s_j} = \left [ \begin{array}{ccc:c} 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.1 \\ 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.1 \\ 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.3 & 0.1 \\ \hdashline0.1 & 0.1 & 0.1 & 0.7 \end{array} \right ] \end{aligned} }[/math]

正例

我们可以看到,123行都是一样的,所以把他们分在一组,并把状态4分在另外一组,看起来像是一个合理的正例。

接下来我们来计算一下。

第1组的状态1到第1组的状态2,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_1 A_1} = p_{A_1 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_1} p_{s_1 s_m} = p_{s_1 s_1} + p_{s_1 s_2} + p_{s_1 s_3} = 0.3 \times 3 = 0.9 }[/math]

第1组的状态1到第2组的状态4,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_1 A_2} = p_{A_1 A_2} = \sum_{s_m \in A_2} p_{s_1 s_m} = p_{s_1 s_4} = 0.1 }[/math]

第2组的状态4到第1组的状态1,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_4 A_1} = p_{A_2 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_1} p_{s_4 s_m} = p_{s_4 s_1} + p_{s_4 s_2} + p_{s_4 s_3} = 0.1 \times 3 = 0.3 }[/math]

第2组的状态4到第2组的状态4,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_4 A_2} = p_{A_2 A_2} = \sum_{s_m \in A_2} p_{s_4 s_m} = p_{s_4 s_4} = 0.7 }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{aligned} P = P_{A_k A_l} = \left [ \begin{array}{c:c} 0.9 & 0.1 \\ \hdashline0.3 & 0.7 \end{array} \right ] \end{aligned} }[/math]

反例

现在我们来看一个反例:把状态12分为一组,状态34分为另一组,

同样的,我们来计算一下。这次我们需要对3和4分开计算了。

第1组的状态1到第1组的状态2,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_1 A_1} = p_{A_1 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_1} p_{s_1 s_m} = p_{s_1 s_1} + p_{s_1 s_2} = 0.3 \times 2 = 0.6 }[/math]

第1组的状态1到第2组的状态3,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_1 A_2} = p_{A_1 A_2} = \sum_{s_m \in A_2} p_{s_1 s_m} = p_{s_1 s_3} + p_{s_1 s_4} = 0.4 }[/math]

第2组的状态3到第1组的状态1,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_3 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_1} p_{s_4 s_m} = p_{s_3 s_1} + p_{s_3 s_2} = 0.3 \times 2 = 0.6 }[/math]

第2组的状态4到第1组的状态1,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_4 A_1} = \sum_{s_m \in A_2} p_{s_4 s_m} = p_{s_4 s_1} + p_{s_4 s_2} = 0.1 \times 2 = 0.2 }[/math]

这里我们就能看到,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{s_3 A_1} \neq p_{s_4 A_1} }[/math],当同一组的两个状态[math]\displaystyle{ s_3 }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ s_4 }[/math]对其他组的转移概率不一样的话,如果我们强行按照这样来分组(也没办法强行,因为我们不知道[math]\displaystyle{ p_{A_2 A_1} = p_{s_3 A_1} }[/math]还是[math]\displaystyle{ p_{A_2 A_1} = p_{s_4 A_1} }[/math]),假设[math]\displaystyle{ p_{A_2 A_1} = 0.6 }[/math],我们会发现这样的粗粒化结果违背了一开始的定义,即粗粒化后的转移概率对所有的初始微观状态[math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math]都适用。因为当[math]\displaystyle{ \pi = s_4 }[/math]的时候,[math]\displaystyle{ p_{A_2 A_1} = 0.6 }[/math]这个转移概率就是错的,即使[math]\displaystyle{ \pi \neq s_4 }[/math],任何初始微观状态都会在某时刻达到[math]\displaystyle{ s_4 }[/math]并导致转移概率出错。

一个更复杂的正例

这个三个相同状态的例子可能稍微有点简单,接下来我们来看一个稍微复杂一点的例子:

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{aligned} P = P_{s_i s_j} = \left [ \begin{array}{cc:cc} 0.2 & 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.1 \\ 0.4 & 0.2 & 0.1 & 0.3 \\ \hdashline0.2 & 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.5 \\ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0 & 0.7 \end{array} \right ] \end{aligned} }[/math]

对于这个马尔科夫矩阵,[math]\displaystyle{ \{\{1,2\}, \{3,4\}\} }[/math]是一个lumpable的分组。分组后的转移矩阵为: [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{aligned} P = P_{A_k A_l} = \left [ \begin{array}{c:c} 0.6 & 0.4 \\ \hdashline0.3 & 0.7 \end{array} \right ] \end{aligned} }[/math]

基于Lumpability的粗粒化方法

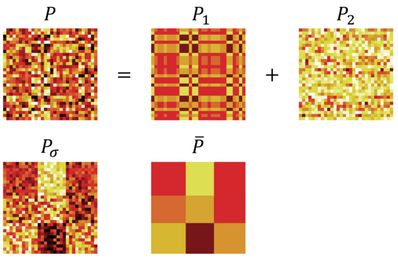

由上面的lumpability公式(3)和例子中我们能获得一个直观上的说法:当马尔科夫矩阵存在block结构,或者状态明显可被分成几类的时候,根据这样的partition,该矩阵就会lumpable,如图2中的[math]\displaystyle{ \bar{P} }[/math]所示,把相同的状态(行向量)分成一类的partition显然lumpable。

但是,有时候有些lumpable的矩阵的状态排序被打乱了(如图一中的[math]\displaystyle{ P_1 }[/math]),或者矩阵包含了如[math]\displaystyle{ P_2 }[/math]的噪声(如图2中的[math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ P = P_1 + P_2 }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ P_1^TP_2 = 0 }[/math])。

我们在实际问题中很多时候要面对的是像[math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]这样的矩阵,我们既无法确定它是否lumpable,也无法决定它的partition,我们甚至不知道它的马尔科夫秩。

在这种情况下,Anru Zhang[3]的文章中提供了一种寻找最优partition的方法,通过此方法我们能找到最优的partition,代入这个partition我们就能通过上面的充分必要条件来决定一个马尔科夫矩阵是否lumpable。具体步骤如下:

- 先获取一个n*n维的马尔科夫矩阵P,或者是马尔科夫链的频率采样;

- 获取r<n 的马尔科夫秩,或指定一个r;

- 对P进行SVD分解,[math]\displaystyle{ P = U \Sigma V^T }[/math],其中U为左奇异向量,V为右奇异向量。

- 通过下列公式得到最优partition [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega_1, \Omega_2, ... , \Omega_r }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega_1, \Omega_2, ... , \Omega_r = argmin_{\Omega_1, \Omega_2, ... , \Omega_r} min_{v_1, v_2, ... , v_r} \sum_{s=1}^r \sum_{i \in \Omega_s} || V_{[i,:r]} - v_s ||_2^2 }[/math]

其中,[math]\displaystyle{ v_s }[/math]是第[math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math]类[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega_s }[/math]的特征向量。

这个算法的意思是在最优的partition中,[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega_s }[/math]中的状态[math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]的右奇异向量会和[math]\displaystyle{ v_s }[/math]距离最小,也就是说,让每个微观态的右特征向量和它对应的宏观态的右特征向量尽可能接近。

这个看起来非常眼熟,其实它就是在做kMeans聚类算法。让[math]\displaystyle{ v_s }[/math]和组里的[math]\displaystyle{ V[i:r] }[/math]距离最小的方法,就是让[math]\displaystyle{ v_s }[/math]成为[math]\displaystyle{ V[i:r] }[/math]这若干个点的中心。

回顾一下kMeans算法把n个点聚成r类的目标函数,其中第[math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]个点被归到第[math]\displaystyle{ c^i }[/math]类,而[math]\displaystyle{ \mu_j }[/math]为第[math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]类点的中心点:

[math]\displaystyle{ J(c^1, ... , c^n, \mu_1, ... , \mu_r) = \sum_{i=1}^n || x_i - \mu_{c^i} ||^2 }[/math]

我们看到这两个目标函数是非常相似的。所以,我们就可以通过上述算法或者kMeans来获取最优partition,然后根据这个partition来判断马尔科夫矩阵的lumpability。

因果涌现

有效信息

有效信息相关详情请参照因果涌现词条。

Dynamical Reversibility 动力学可逆性

动力学可逆性相关详情请参照因果涌现词条。

因果态

因果态相关详情请参照计算力学词条。

不同粗粒化方法之间的异同

动力学可逆性 v.s. Lumpability

在lumpability的图1中我们提到了lumpable的马尔科夫矩阵可以被重新排列成几个block,这种lumpable的矩阵的动力学可逆性也会很高,在这种情况下动力学可逆性和 Lumpability是一致的。

在没有明显block结构的情况下,我们可以使用上述的SVD+kMeans方式找到最优的lumpability partition并决定它的lumpability。我们在一个动力学可逆性比较高(有明显的因果涌现)的国际贸易网的例子上尝试了一下,却发现该网络上的最优lumpability partition宏观结果的动力学可逆性并不高。这现象说明:

- Lumpability最优的partition不等于可逆性最优的partition。

- Lumpability的分组数量是基于马尔科夫秩的,而可逆性的分组数量是对奇异值谱的截断位置。

(未完待续)

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Coarse graining. Encyclopedia of Mathematics. URL: http://encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Coarse_graining&oldid=16170

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Buchholz, Peter. "Exact and ordinary lumpability in finite Markov chains." Journal of applied probability 31.1 (1994): 59-75.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Zhang, Anru, and Mengdi Wang. "Spectral state compression of markov processes." IEEE transactions on information theory 66.5 (2019): 3202-3231.

- ↑ Singh, Satinder, Tommi Jaakkola, and Michael Jordan. "Reinforcement learning with soft state aggregation." Advances in neural information processing systems 7 (1994).

- ↑ Kemeny, John G., and J. Laurie Snell. Finite markov chains. Vol. 26. Princeton, NJ: van Nostrand, 1969. https://www.math.pku.edu.cn/teachers/yaoy/Fall2011/Kemeny-Snell_Chapter6.3-4.pdf