“计算社会科学”的版本间的差异

18621066378(讨论 | 贡献) |

18621066378(讨论 | 贡献) |

||

| 第402行: | 第402行: | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| + | *[http://cress.soc.surrey.ac.uk/s4ss/ On-line book "Simulation for the Social Scientist" by Nigel Gilbert and Klaus G. Troitzsch, 1999, second edition 2005] | ||

| + | *[http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/JASSS.html Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation] | ||

| + | *[https://web.archive.org/web/20110516072744/http://cmol.nbi.dk/models/ Agent based models for social networks, interactive java applets] | ||

| + | *[https://web.archive.org/web/20090827052722/http://www.personal.kent.edu/~bcastel3/ Sociology and Complexity Science Website] | ||

== 外部链接 == | == 外部链接 == | ||

2020年5月11日 (一) 17:30的版本

此词条暂由彩云小译翻译,未经人工整理和审校,带来阅读不便,请见谅。

本词条的框架如下,大家可以选取感兴趣的部分,在对应的位置,写上自己的名字

- 计算社会科学定义————

- 计算社会科学发展历史————

- 计算社会科学的研究方法————

- 计算社会科学的应用与分支————

翻译整理截止日期:2020.5.8 18:00

计算社会科学(Computational Social Science)是一门融合社会科学、数据科学和统计学等学科的新兴交叉学科,强调用大数据的方式来研究社会科学中的核心问题,是社会科学在大数据时代下发展的产物。领域包括计算经济学、计算社会学、动态学、文化学以及社交和传统媒体的内容自动分析。它着重于通过社会模拟、建模、网络分析和媒体分析来调查社会和行为关系和互动。[1]

定义

There are two terminologies that relate to each other: Social Science Computing (SSC) and Computational Social Science (CSS). In literature, CSS is referred to the field of social science that uses the computational approaches in studying the social phenomena.

There are two terminologies that relate to each other: Social Science Computing (SSC) and Computational Social Science (CSS). In literature, CSS is referred to the field of social science that uses the computational approaches in studying the social phenomena.

有两个相互关联的术语: 社会科学计算(SSC)和计算社会科学(CSS)。

在文献中,计算社会科学指的是社会科学领域,它使用计算方法来研究社会现象。

On the other hand, SSC is the field in which computational methodologies are created to assist in explanations of social phenomena.

On the other hand, SSC is the field in which computational methodologies are created to assist in explanations of social phenomena.

另一方面,社会科学计算是一个领域,其中计算方法创建,以协助解释社会现象。

Computational social science revolutionizes both fundamental legs of the scientific method: empirical research, especially through big data, by analyzing the digital footprint left behind through social online activities; and scientific theory, especially through computer simulation model building through social simulation.[2][3] It is a multi-disciplinary and integrated approach to social survey focusing on information processing by means of advanced information technology. The computational tasks include the analysis of social networks, social geographic systems,[4] social media content and traditional media content.

Computational social science revolutionizes both fundamental legs of the scientific method: empirical research, especially through big data, by analyzing the digital footprint left behind through social online activities; and scientific theory, especially through computer simulation model building through social simulation. It is a multi-disciplinary and integrated approach to social survey focusing on information processing by means of advanced information technology. The computational tasks include the analysis of social networks, social geographic systems, social media content and traditional media content.

计算社会科学彻底改变了科学方法的两个基本支柱: 实证研究,特别是通过大数据,通过分析社会在线活动留下的数据痕迹; 科学理论,特别是通过社会模拟建立计算机模拟模型。利用先进的信息技术进行以信息处理为核心的社会调查是一种多学科、综合的方法。计算任务包括分析社交网络、社交地理系统、社交媒体内容和传统媒体内容。

概念演化

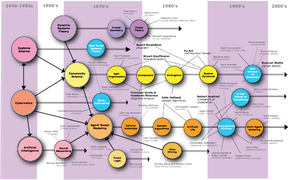

计算社会科学的产生并非突然出现,而是在技术发展下催生出来的跨学科研究。如果大致来分,可以分为4个阶段来看计算社会科学的演化进程。

1、计算社会科学的源头 计算社会科学是一个较现代的学科,最远可以追溯到20世纪中后期电脑刚刚发明的时候,在20世纪60年代,社会科学家开始使用电脑进行统计数据分析,出现了计算社会科学的第一代创始人:Herbert A. Simon(1916-2001)、Karl W.Deutsch(1912-1992)、Harold Guetzkow(1915-2008)、Thomas C. Schelling(1921)、他们更偏向计算社会科学理论方面的研究。

2、计算社会科学的蓄势 传统的定量的社会科学分析方法,偏向于统计分析的方法,但是社会系统作为一个复杂的系统,涉及到大量(但个数仍有限)的异构实体的相互作用,这些是用简单的统计分析是无法精确刻画的,而19世纪末网络科学迅速发展为社会分析提供了强有力的分析手段。

2007年,“小世界网络之父”奠基人邓肯·瓦茨在 Nature 发表了题为《A twenty-first century science》的文章,这成为计算社会科学时代即将来临的标志之一。这篇文章采用了网络分析的方法来分析社会现象中的网络偏好以及个体选择的问题。关于这篇文章集智俱乐部的发表过相关的解读文章:计算社会科学时代的来临 | 小世界网络之父邓肯·瓦茨经典回顾

A twenty-first century science [2007]Duncan J. Watts查看详情页查看原文

关于网络科学的综述,可以看美国东北大学网络科学家Alessandro Vespignani于2018年6月发表在Nature上的一篇综述文章《Twenty years of network science》 Twenty years of network science [2018]ALESSANDRO VESPIGNANI查看详情页查看原文

集智俱乐部也翻译了相关的报道:小世界网络、偏好依附机制、跨学科研究——网络科学20年

3、计算社会科学的诞生 计算社会科学标记性的诞生,应该是起源于2009年2月6日,15名来自社会科学、计算机科学和物理学的重要科学家联名在Science上发表了《Computer Social Science》。

计算社会科学诞生的标志 这篇文章主要是阐述了计算社会科学正对我们的社会生活产生深远的影响,但是也同样面临着数据获取和隐私等方面的障碍。关于这篇文章集智俱乐部的发表过相关的解读文章:Science经典回顾:计算社会科学诞生宣言

Computational Social Science [2009]David Lazer,Alex Pentland,Lada Adamic查看详情页查看原文

4、计算社会科学的进一步确立 另外,在2012年,R. Conte,C. Cioffi-Revilla等14位欧美学者在《The European Physical Journal Special Topics》(第1期)上联合发布了一份《计算社会科学宣言》(后文简称“宣言”),力图呼唤一场社会科学革命。《宣言》从机遇、技术发展、方法创新、面临的挑战和预期的影响等五个方面全景式的说明了计算社会科学发展现状及其未来的方面。

研究历史

本词条改编自相应维基百科页面

大背景

In the past four decades, computational sociology has been introduced and gaining popularity 模板:According to whom. This has been used primarily for modeling or building explanations of social processes and are depending on the emergence of complex behavior from simple activities.[5] The idea behind emergence is that properties of any bigger system do not always have to be properties of the components that the system is made of.[6] The people responsible for the introduction of the idea of emergence are Alexander, Morgan, and Broad, who were classical emergentists. The time at which these emergentists came up with this concept and method was during the time of the early twentieth century. The aim of this method was to find a good enough accommodation between two different and extreme ontologies, which were reductionist materialism and dualism.[5]

计算社会学在过去的四十年里诞生并获得了极大的关注。它最先是用在建模和解释那些从简单的活动中涌现出复杂行为的社会过程。[5] “涌现”背后的思想就是一个大系统表现出来的属性并不一定格式其组成部分的属性。[7] 引入涌现思想的人是Alexander, Morgan, 和 Broad,这些都是古典的涌现学家(emergentist),他们在二十世纪初期提出了这个概念和方法,目的是为同一论(reductionist materialism)和二元论(dualism)这两个针锋相对的观念体系寻找一个足够好的平衡。

While emergence has had a valuable and important role with the foundation of Computational Sociology, there are those who do not necessarily agree. One major leader in the field, Epstein, doubted the use because there were aspects that are unexplainable. Epstein put up a claim against emergentism, in which he says it "is precisely the generative sufficiency of the parts that constitutes the whole's explanation".[5]

尽管涌现思想在计算社会学的建立中扮演着重要的角色,却也有人不同意这个思想,代表人物就是爱泼斯坦(Joshua M. Epstein)。爱泼斯坦怀疑涌现思想的作用,因为有些方面是无法解释的。他作出了一番反对涌现思想的宣言:“各个部分的生成性自足构成了全部现象的解释(the generative sufficiency of the parts that constitutes the whole's explanation)”[5]

Agent-based models have had a historical influence on Computational Sociology. These models first came around in the 1960s, and were used to simulate control and feedback processes in organizations, cities, etc. During the 1970s, the application introduced the use of individuals as the main units for the analyses and used bottom-up strategies for modeling behaviors. The last wave occurred in the 1980s. At this time, the models were still bottom-up; the only difference is that the agents interact interdependently.[5]

基于主体的模型(Agent-based models)对计算社会学有着历史性的意义。这些模型最早出现在20世纪六十年代,用于模拟组织和城市等的控制和反馈机制。在七十年代时,基于主体的建模引入了个体(individual)作为主要的建模单元进行分析,闭关使用自底向上的策略来对行为建模。八十年代时发生的主要改变则是主体们的交互时独立的。[5]

Systems theory and structural functionalism

In the post-war era, Vannevar Bush's differential analyser, John von Neumann's cellular automata, Norbert Wiener's cybernetics, and Claude Shannon's information theory became influential paradigms for modeling and understanding complexity in technical systems. In response, scientists in disciplines such as physics, biology, electronics, and economics began to articulate a general theory of systems in which all natural and physical phenomena are manifestations of interrelated elements in a system that has common patterns and properties. Following Émile Durkheim's call to analyze complex modern society sui generis,[8] post-war structural functionalist sociologists such as Talcott Parsons seized upon these theories of systematic and hierarchical interaction among constituent components to attempt to generate grand unified sociological theories, such as the AGIL paradigm.[9] Sociologists such as George Homans argued that sociological theories should be formalized into hierarchical structures of propositions and precise terminology from which other propositions and hypotheses could be derived and operationalized into empirical studies.[10] Because computer algorithms and programs had been used as early as 1956 to test and validate mathematical theorems, such as the four color theorem,[11] some scholars anticipated that similar computational approaches could "solve" and "prove" analogously formalized problems and theorems of social structures and dynamics.

系统论和功能主义

在战后时期,万尼瓦尔·布希的微分分析器、约翰·冯·诺伊曼的细胞自动机、诺伯特·维纳的模控学 与克劳德·夏农的信息论在技术系统中成为模拟与暸解复杂度具有影响力的典范。相对应地,在像是物理学、生物学、电子学,和经济学等学门的科学家开始表述一种一般性的系统理论,其中所有自然与物理现象皆为一个系统中具有相同模式与性质的相关元素的展现。 随着艾弥尔·涂尔干以实事求是的方式分析复杂现代社会的呼声[12] ,战后结构功能主义社会学家如塔尔科特·帕森斯利用这些构成元素之间系统化与阶层化互动的理论,来尝试生成宏大而统一的社会学理论,例如四种功能(AGIL paradigm)[9]。 如George Homans等社会学家辩称社会理论应该被形式化(正规化)(formalized),成为命题和精确术语的阶层结构,其他的命题与假设可以从中被推演出来并操作化以进行实证研究。[10] 由于电脑算法与程式早在1956年就已用来测试和验证数学定理,[13]例如四色定理,社会科学家与系统动力学家预期类似的计算取径可以类比地“解决”与“证明”正规化的问题,和社会结构与动力的理论。

Macrosimulation and microsimulation

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, social scientists used increasingly available computing technology to perform macro-simulations of control and feedback processes in organizations, industries, cities, and global populations. These models used differential equations to predict population distributions as holistic functions of other systematic factors such as inventory control, urban traffic, migration, and disease transmission.[14][15] Although simulations of social systems received substantial attention in the mid-1970s after the Club of Rome published reports predicting that policies promoting exponential economic growth would eventually bring global environmental catastrophe,[16] the inconvenient conclusions led many authors to seek to discredit the models, attempting to make the researchers themselves appear unscientific.[17][18] Hoping to avoid the same fate, many social scientists turned their attention toward micro-simulation models to make forecasts and study policy effects by modeling aggregate changes in state of individual-level entities rather than the changes in distribution at the population level.[19] However, these micro-simulation models did not permit individuals to interact or adapt and were not intended for basic theoretical research.[20]

宏观模拟与微观模拟

到了1960年代晚期与1970年代早期,社会科学家使用更为可得的电脑科技对组织、产业、城市,与全球人口进行控制与回馈过程的宏观模拟。这些模型使用微分方程,将人口分布视为其他系统性因素(如存货控管、都市交通、迁徙、疾病传染等)的整体计算型函数(holistic functions)来进行预测。罗马俱乐部根据对于全球经济的模拟而出版了预测全球环境浩劫的报告。[21][22] 尽管在这份报告发表后的1970年代中期,对社会体系的模拟因而得到了大量的关注,[23] 然而模型的结果被认为对于模型的假设非常敏感(在罗马俱乐部的例子中,仅有少数的证据支持),亦暂时使得这初生的领域失去可信度。[17][24] 对于利用计算工具来预测宏观的社会与经济行为产生的怀疑渐增,因此社会科学家将其注意力转向了微观模拟模型(microsimulation),借由模拟个人层级个体的状态渐进改变,而非人口层级的分布的改变,社会学家们作出了预测,也研究政策的效果[25]。 然而,这些微观模拟模型并未允许个体进行互动或适应,其目的也非基本理论研究[20]。

元胞自动机与基于主体的建模

20世纪七十到八十年代,数学家和物理学家尝试建模和分析怎样从简单的单元,比如原子中,产生全局现象,比如复杂材料才低温、磁场、和湍流中的属性。[26] 科学家们使用元胞自动机(Celluer Automata),设定了一个只由方格组成的系统,每个方格就是一个“元胞(cell)”。每个元胞只能有有限个状态,元胞在各个状态间的转换条件只由紧贴着该元胞的周围元胞状态决定。元胞自动机与人工智能技术和微型计算机的所获得的进步一同为混沌理论和复杂系统等研究领域的建立做出重大贡献,同时也重新唤起了人们在理解交叉学科的复杂物理和社会系统的兴趣。众多致力于研究复杂科学的科研组织也是建立于这个时候:圣塔菲研究所由一群来自洛斯阿拉莫斯国家实验室的物理学家在1984年发起,密歇根大学的BACH小组也是在八十年代中期成立的。

这一轮元胞自动机的研究范式催生了使用基于主体建模(Agent-based Modeling)的第三次社会模拟浪潮。和宏观模拟类似,这些模型强调了自底向上的设计思想,但采用了四个不同于宏观建模的假设:自主(autonomy)、独立(interdependency)、简单规则(simple rules)、和适应性行为(adaptive behavior)。[20] 相比于预测的准确度,基于主体的建模更加强调理论的建立。[27] 在1981年,数学家与政治学家罗伯特·阿克塞尔罗德与演化生物学家威廉·汉密尔顿一同在《Science》杂志上发表了一篇名为《合作的进化(The Evolution of Cooperation)》的经典论文,其中使用了基于主体的建模来展示了在囚徒困境的博弈中,当主体们(agents)只遵循简单的、自利的规则时,也可以在互惠的原则上建立稳定的社会合作。[28] 阿克塞尔罗德和汉密尔顿展示了每个主体只要遵循(1)第一轮时选择合作(2)下一轮重复上一轮对方的做法这两条简单规则,就可以在没有社会权威的情况下建立起合作与惩罚的规范。[28] 九十年代学者们如William Sims Bainbridge, Kathleen Carley, Michael Macy,和John Skvoretz建立起了广义互惠、偏见、社会影响和组织信息处理等主题的基于主体的模型。在1999年,Nigel Gilbert发表了第一本关于社会模拟的教科书《Simulation for the social scientist》,并创立了与其相关的期刊《Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation》。

数据挖掘与社交网络分析

Independent from developments in computational models of social systems, social network analysis emerged in the 1970s and 1980s from advances in graph theory, statistics, and studies of social structure as a distinct analytical method and was articulated and employed by sociologists like James S. Coleman, Harrison White, Linton Freeman, J. Clyde Mitchell, Mark Granovetter, Ronald Burt, and Barry Wellman.[29] The increasing pervasiveness of computing and telecommunication technologies throughout the 1980s and 1990s demanded analytical techniques, such as network analysis and multilevel modeling, that could scale to increasingly complex and large data sets. The most recent wave of computational sociology, rather than employing simulations, uses network analysis and advanced statistical techniques to analyze large-scale computer databases of electronic proxies for behavioral data. Electronic records such as email and instant message records, hyperlinks on the World Wide Web, mobile phone usage, and discussion on Usenet allow social scientists to directly observe and analyze social behavior at multiple points in time and multiple levels of analysis without the constraints of traditional empirical methods such as interviews, participant observation, or survey instruments. Continued improvements in machine learning algorithms likewise have permitted social scientists and entrepreneurs to use novel techniques to identify latent and meaningful patterns of social interaction and evolution in large electronic datasets.

和其他社会系统计算模型的发展轨迹不同,社交网络分析(Social Network Analysis)诞生自20世纪七十到八十年代,是图论、统计学和社会结构研究等科研进展所催生出来的分析方法,被许多社会学家,如 James Samuel Coleman, Harrison White, Linton Freeman, J. Clyde Mitchell, Mark Granovetter, Ronald Burt, and Barry Wellman等采用。[30] 八十到九十年代计算和通信技术的持续普及呼唤着网络科学,多层次建模等可以适用于越来越复杂和大体量数据集的分析技术。最近的计算社会学浪潮并没有使用计算机模拟,而是使用了网络分析和高级统计技术对计算机数据库里的行为数据做分析。电子邮件、即时通信消息、万维网上的超链接、手机使用数据、新闻组内的讨论内容等电子记录让社会学家们得以在多时间点多个层面上直接观察和分析社会行为,避免了访谈、参与观察等传统实证方法(traditional empirical methods)的约束。[31] 机器学习算法的持续进步则更进一步允许社会学家和企业发现大规模数据集中隐藏的社会交互和演化的模式。 [32][33]

The automatic parsing of textual corpora has enabled the extraction of actors and their relational networks on a vast scale, turning textual data into network data. The resulting networks, which can contain thousands of nodes, are then analysed by using tools from Network theory to identify the key actors, the key communities or parties, and general properties such as robustness or structural stability of the overall network, or centrality of certain nodes.[35] This automates the approach introduced by quantitative narrative analysis,[36] whereby subject-verb-object triplets are identified with pairs of actors linked by an action, or pairs formed by actor-object.[34]

语料库自动解析技术可以大规模地抽取文本中的实体,以及实体间的关系,以将文本形式数据转化成网络形式数据。生成的网络可以包含成千上万个节点,随后应用网络理论等工具加以分析,即可发现关键结点、重点社群等,以及更加广泛的网络属性,比如健壮性和结构稳定性,或者结构洞等。[37]如此,我们可以自动执行定量叙事分析(quantitative narrative analysis)中的技术,[38]识别“主语-谓语-宾语”这样的三元组或者“主语-宾语”这样的二元组。[34]

计算内容分析

Content analysis has been a traditional part of social sciences and media studies for a long time. The automation of content analysis has allowed a "big data" revolution to take place in that field, with studies in social media and newspaper content that include millions of news items. Gender bias, readability, content similarity, reader preferences, and even mood have been analyzed based on text mining methods over millions of documents.[39][40][41][42][43] The analysis of readability, gender bias and topic bias was demonstrated in Flaounas et al.[44] showing how different topics have different gender biases and levels of readability; the possibility to detect mood shifts in a vast population by analysing Twitter content was demonstrated as well.[45]

The analysis of vast quantities of historical newspaper content has been pioneered by Dzogang et al.,[46] which showed how periodic structures can be automatically discovered in historical newspapers. A similar analysis was performed on social media, again revealing strongly periodic structures.[47]

内容分析(content analysis)一直以来都是社会科学和媒体研究的传统组成部分。内容分析的自动化通过研究社交媒体和报刊杂志上数百万计的新闻内容,使得“大数据革命”惠及社会科学。性别偏向、可读性、内容相似度、读者偏好、甚至情绪等都文本挖掘方法在数百万文档里研究过了。[48][49][50][51][52]

Flaounas et al.[53]这篇论文中对于可读性、性别偏向和主题偏向等进行了分析。论文展示了不同的主题有不同的性别偏向和可读性,还探讨了通过分析Twitter内容来识别人群的情绪变化的可能性。[54]

Dzogang et al.[55] 是大规模历史新闻内容分析的先驱,他们的研究展示了周期性结构如何可以通过历史新闻内容自动识别出来。在社交媒体领域也有相似的分析,同样揭示了很强的周期结构。[56]

研究方法

就像伽利略利用望远镜作为关键的观察工具最终获得对物质世界更深刻、更真实的理解一样,计算社会科学家正在学习利用先进和日益强大的计算工具来超越传统的学科。

目前,根据使用环境的不同,计算社会科学方法主要分为五个:

1、 自动信息提取

自动信息提取技术由于可以挖掘实时的数据流,如新闻广播或其他电子报告,不仅可用于异常检测和预警,同时也可用于监测趋势和评估干预和项目执行等,是计算社会科学数据收集的一个重要方式。

2、 社交网络分析(SNA)

将人或者社区看作一个点,用边表示人和人之间或者社区和社区之间可能存在的相互依赖关系,这样就可以构成一个社会网络,利用网络科学的方法对社会网络进行分析,挖掘出背后的逻辑,就是社交网络分析。联盟、恐怖组织、贸易体系、认知信仰体系和国家社会体系本身都是常见的社会网络,是社会科学家们感兴趣的研究对象。

3、地理空间分析(又被称为社会地理信息系统、地理信息系统、社会GIS]

地理信息系统(GIS)最初是社会地理学家和制图员研究地理现象的可视化工具和空间分析的工具。目前在社会科学中有了许多应用,比如在犯罪学和区域经济学应用社会GIS可以有效的量化冲突,与其他的量化技术结合在一起可以产生一些使用数学和统计模型无法获得的有趣的见解。

=== 4、 复杂系统建模 ===

复杂系统建模是指采用复杂系统的基本方法,比如神经网络建模、基于主体的建模方法、遗传算法、粒子群优化算法、蚁群优化算法应用在社会科学网络中,为社会科学中的非均衡系统的动态分析提供了理论支持。如恐怖袭击、发展中国家的财富和贫困,政治不稳定,外国援助分布和国内和国际冲突等。

5、 社会仿真模型

因为很多社会事件是无法在系统上进行实验的, 所以采用仿真模拟的办法来对研究分析某一特定的系统和策略,从而达到分析社会现象的办法,成为社会仿真模型。

同样的,每个方法下面也被系统的划分为多个模型,例如计算社会模拟模型包括系统动力学,微观分析模型,排队模型,细胞自动机,多智能体模型,学习和演化模型,包括一些混合动力,例如,结合系统动力学和代理模型(Agent Based Models)。另外,这五种方法之间的几种组合也很常见,如在由反弹道导弹模拟时引入表达社会复杂性的幂律分布模型。

这部分的详细内容可以看社会复杂性中心,Krasnow先进研究所,美国乔治梅森大学教授Claudio Cioffi-Revilla 出版的《 Introduction to Computational Social Science: Principles and Applications》,现在也有了中文的翻译版本,《计算社会科学原则与应用》。

Computational social science [2010]Claudio Cioffi‐Revilla<a target='_blank' href='/paper?id=62b3c07e-5bcc-11ea-9bda-0242ac1a0005'>查看详情页</a><a target='_blank' href='/outlink?target=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wics.95#accessDenialLayout'>查看原文</a>

Challenges

Computational sociology, as with any field of study, faces a set of challenges.[57] These challenges need to be handled meaningfully so as to make the maximum impact on society.

Levels and their interactions

Each society that is formed tends to be in one level or the other and there exists tendencies of interactions between and across these levels. Levels need not only be micro-level or macro-level in nature. There can be intermediate levels in which a society exists say - groups, networks, communities etc.[57]

The question however arises as to how to identify these levels and how they come into existence? And once they are in existence how do they interact within themselves and with other levels?

If we view entities (agents) as nodes and the connections between them as the edges, we see the formation of networks. The connections in these networks do not come about based on just objective relationships between the entities, rather they are decided upon by factors chosen by the participating entities.[58] The challenge with this process is that, it is difficult to identify when a set of entities will form a network. These networks may be of trust networks, co-operation networks, dependence networks etc. There have been cases where heterogeneous set of entities have shown to form strong and meaningful networks among themselves.[59][60]

As discussed previously, societies fall into levels and in one such level, the individual level, a micro-macro link[61] refers to the interactions which create higher-levels. There are a set of questions that needs to be answered regarding these Micro-Macro links. How they are formed? When do they converge? What is the feedback pushed to the lower levels and how are they pushed?

Another major challenge in this category concerns the validity of information and their sources. In recent years there has been a boom in information gathering and processing. However, little attention was paid to the spread of false information between the societies. Tracing back the sources and finding ownership of such information is difficult.

Culture modeling

The evolution of the networks and levels in the society brings about cultural diversity.[62] A thought which arises however is that, when people tend to interact and become more accepting of other cultures and beliefs, how is it that diversity still persists? Why is there no convergence? A major challenge is how to model these diversities. Are there external factors like mass media, locality of societies etc. which influence the evolution or persistence of cultural diversities?[citation needed]

Experimentation and evaluation

Any study or modelling when combined with experimentation needs to be able to address the questions being asked. Computational social science deals with large scale data and the challenge becomes much more evident as the scale grows. How would one design informative simulations on a large scale? And even if a large scale simulation is brought up, how is the evaluation supposed to be performed?

Model choice and model complexities

Another challenge is identifying the models that would best fit the data and the complexities of these models. These models would help us predict how societies might evolve over time and provide possible explanations on how things work.[63]

Generative models

Generative models helps us to perform extensive qualitative analysis in a controlled fashion. A model proposed by Epstein, is the agent-based simulation, which talks about identifying an initial set of heterogeneous entities (agents) and observe their evolution and growth based on simple local rules.[64]

But what are these local rules? How does one identify them for a set of heterogeneous agents? Evaluation and impact of these rules state a whole new set of difficulties.

Heterogeneous or ensemble models

Integrating simple models which perform better on individual tasks to form a Hybrid model is an approach that can be looked into[citation needed]. These models can offer better performance and understanding of the data. However the trade-off of identifying and having a deep understanding of the interactions between these simple models arises when one needs to come up with one combined, well performing model. Also, coming up with tools and applications to help analyse and visualize the data based on these hybrid models is another added challenge.

以下部分内容来自中文wiki:繁体字的部分主要用于插入文献即可

数据库

計算社會科學日益依賴逐漸增加的大型資料庫,目前正由幾個跨領域計畫建置中或維護中的資料庫有:

- 塞莎特(Seshat):全球歷史的資料庫,內容系統性的收集了關於內容群體政治社會組織的資訊,以及社會如何演化等。塞莎特隸屬於演化研究所,演化研究所為非營利智庫,目標為「利用演化科學來解決現實世界問題」。

- D-PLACE:地方、語言、文化和環境資料庫,提供超過1400個人類社會形態的資料[65]。

- 文化演化圖集:是由彼得·百富勤(Peter N. Peregrie)所建立的考古資料庫[66]。

- CHIA:即歷史分析的協作資訊(Collaborative Information for Historical Analysis),是由匹茲堡大學主持的多學科合作項目,旨在將歷資訊資訊建檔,將數據與全球各地的研究機構連結起來。

- 國際社會歷史研究所(International Institute of Social History):收集關於勞動關係,工人和勞動的全球社會歷史的資料。

- Human Relations Area Files eHRAF Archaeology[67]。

- Human Relations Area Files eHRAF World Cultures[68]。

- Clio-Infra:從公元前1800年到現在的全球社會樣本的經濟績效和社會福利其他方面的資料庫。

對大量歷史報紙內容的分析率先顯示了如何自動發現週期性結構[69][70] ,對社群媒體進行類似的分析,也能看到明顯的週期性結構[71]。

计算社会科学日益依赖大型的资料库,目前正由几个跨领域计划或维护中的资料库:

- Seshat:全球历史的资料库,内容系统性的收集了关于内容群体政治社会组织的资讯,以及社会如何演化等。Seshat隶属于演化研究所,演化研究所为非营利智库,目标为“利用演化科学来解决现实世界问题”。

- D-PLACE:地方、语言、文化和环境资料库,提供超过1400个人类社会形态的资料[5]。

- 文化演化图集:是由彼得·百富勤(Peter N. Peregrie)所建立的考古资料库[6]。

- CHIA:即历史分析的协作资讯(Collaborative Information for Historical Analysis),是由匹兹堡大学主持的多学科合作项目,旨在将历资讯资讯建档,将数据与全球各地的研究机构连结起来。

- 国际社会历史研究所(International Institute of Social History):收集关于劳动关系,工人和劳动的全球社会历史的资料。

- Human Relations Area Files eHRAF Archaeology[7]。

- Human Relations Area Files eHRAF World Cultures[8]。

- Clio-Infra:从公元前1800年到现在的全球社会样本的经济绩效和社会福利其他方面的资料库。

- 对大量历史报纸内容的分析率先显示了如何自动发现周期性结构[9][10] ,对社群媒体进行类似的分析,也能看到明显的周期性结构[11]。

The analysis of vast quantities of historical newspaper and book content have been pioneered in 2017, while other studies on similar data showed how periodic structures can be automatically discovered in historical newspapers. A similar analysis was performed on social media, again revealing strongly periodic structures.

对大量历史报纸和书籍内容的分析在2017年开创了先河,而对类似数据的其他研究表明,周期结构可以在历史报纸中自动发现。在社交媒体上也进行了类似的分析,再次揭示了强烈的周期性结构。

Impact

Computational sociology can bring impacts to science, technology and society.[57]

Impact on science

In order for the study of computational sociology to be effective, there has to be valuable innovations. These innovation can be of the form of new data analytics tools, better models and algorithms. The advent of such innovation will be a boon for the scientific community in large.[citation needed]

Impact on society

One of the major challenges of computational sociology is the modelling of social processes[citation needed]. Various law and policy makers would be able to see efficient and effective paths to issue new guidelines and the mass in general would be able to evaluate and gain fair understanding of the options presented in front of them enabling an open and well balanced decision process.[citation needed].

Journals and academic publications

The most relevant journal of the discipline is the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation.

- Complexity Research Journal List, from UIUC, IL

- Related Research Groups, from UIUC, IL

Associations, conferences and workshops

- North American Association for Computational Social and Organization Sciences

- ESSA: European Social Simulation Association

Academic programs, departments and degrees

- University of Bristol "Mediapatterns" project

- Carnegie Mellon University, PhD program in Computation, Organizations and Society (COS)

- University of Chicago

- George Mason University

- PhD program in CSS (Computational Social Sciences)

- MA program in Master's of Interdisciplinary Studies, CSS emphasis

- Portland State, PhD program in Systems Science

- Portland State, MS program in Systems Science

- University College Dublin,

- PhD Program in Complex Systems and Computational Social Science

- MSc in Social Data Analytics

- BSc in Computational Social Science

- UCLA, Minor in Human Complex Systems

- UCLA, Major in Computational & Systems Biology (including behavioral sciences)

- Univ. of Michigan, Minor in Complex Systems

- Systems Sciences Programs List, Portland State. List of other worldwide related programs.

Centers and institutes

North America

- Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA.

- Center for Complex Systems Research, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA.

- Center for Social Complexity, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA.

- Center for Social Dynamics and Complexity, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA.

- Center of the Study of Complex Systems, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

- Human Complex Systems, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- Institute for Quantitative Social Science, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA.

- Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems (NICO), Northwestern University, Evanston, IL USA.

- Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM, USA.

- Duke Network Analysis Center, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

South America

- Modelagem de Sistemas Complexos, University of São Paulo - EACH, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

- Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia de Sistemas Complexos, Centro Brasileiro de Pesquisas Físicas, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

Europe

- Centre for Policy Modelling, Manchester, UK.

- Centre for Research in Social Simulation, University of Surrey, UK.

- UCD Dynamics Lab- Centre for Computational Social Science, Geary Institute for Public Policy, University College Dublin, Ireland.

- Groningen Center for Social Complexity Studies (GCSCS), Groningen, NL.

- Chair of Sociology, in particular of Modeling and Simulation (SOMS), Zürich, Switzerland.

- Research Group on Experimental and Computational Sociology (GECS), Brescia, IT.

Asia

- Bandung Fe Institute, Centre for Complexity in Surya University, Bandung, Indonesia.

See also

- Artificial society

- Simulated reality

- Social simulation

- Agent-based social simulation

- Social complexity

- Computational economics

- Computational epidemiology

- Cliodynamics

- Predictive analytics

参见

参见

References

参考资料

参考资料

- ↑ "The Computational Social Science Society of the Americas official website".

- ↑ DT&SC 7-1: . Introduction to e-Science: From the DT&SC online course at the University of California

- ↑ Hilbert, M. (2015). e-Science for Digital Development: ICT4ICT4D. Centre for Development Informatics, SEED, University of Manchester. ISBN 978-1-905469-54-3. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. https://web.archive.org/web/20150924100018/http://www.seed.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/IDPM/working_papers/di/di-wp60.pdf.

- ↑ Cioffi-Revilla, Claudio (2010). "Computational social science". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics. 2 (3): 259–271. doi:10.1002/wics.95.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Salgado, Mauricio, and Nigel Gilbert. "Emergence and communication in computational sociology." Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 43.1 (2013): 87-110.

- ↑ Macy, Michael W., and Robert Willer. "From factors to actors: computational sociology and agent-based modeling." Annual review of sociology 28.1 (2002): 143-166.

- ↑ Macy, Michael W., and Robert Willer. "From factors to actors: computational sociology and agent-based modeling." Annual review of sociology 28.1 (2002): 143-166.

- ↑ Durkheim, Émile. The Division of Labor in Society. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bailey, Kenneth D. (2006). "Systems Theory". In Jonathan H. Turner. Handbook of Sociological Theory. New York, NY: Springer Science. pp. 379–404. ISBN 978-0-387-32458-6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bainbridge, William Sims (2007). "Computational Sociology". In Ritzer, George (ed.). Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Blackwell Reference Online. doi:10.1111/b.9781405124331.2007.x. hdl:10138/224218. ISBN 978-1-4051-2433-1.

- ↑ Crevier, D. (1993). AI: The Tumultuous History of the Search for Artificial Intelligence. New York, NY: Basic Books. https://archive.org/details/aitumultuoushist00crev.

- ↑ Durkheim, Émile. The Division of Labor in Society. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- ↑ Crevier, D. (1993). AI: The Tumultuous History of the Search for Artificial Intelligence. New York, NY: Basic Books. https://archive.org/details/aitumultuoushist00crev.

- ↑ Forrester, Jay (1971). World Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ↑ Ignall, Edward J.; Kolesar, Peter; Walker, Warren E. (1978). "Using Simulation to Develop and Validate Analytic Models: Some Case Studies". Operations Research. 26 (2): 237–253. doi:10.1287/opre.26.2.237.

- ↑ Meadows, DL; Behrens, WW; Meadows, DH; Naill, RF; Randers, J; Zahn, EK (1974). The Dynamics of Growth in a Finite World. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Gilbert, Nigel; Troitzsch, Klaus (2005). "Simulation and social science". Simulation for Social Scientists (2 ed.). Open University Press. http://cress.soc.surrey.ac.uk/s4ss/.

- ↑ "Computer View of Disaster Is Rebutted". The New York Times. October 18, 1974.

- ↑ Orcutt, Guy H. (1990). "From engineering to microsimulation : An autobiographical reflection". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 14 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(90)90038-F.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Macy, Michael W.; Willer, Robert (2002). "From Factors to Actors: Computational Sociology and Agent-Based Modeling". Annual Review of Sociology. 28: 143–166. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141117. JSTOR 3069238.

- ↑ Forrester, Jay (1971). World Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ↑ Ignall, Edward J.; Kolesar, Peter; Walker, Warren E. (1978). "Using Simulation to Develop and Validate Analytic Models: Some Case Studies". Operations Research. 26 (2): 237–253. doi:10.1287/opre.26.2.237.

- ↑ Meadows, DL; Behrens, WW; Meadows, DH; Naill, RF; Randers, J; Zahn, EK (1974). The Dynamics of Growth in a Finite World. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ↑ "Computer View of Disaster Is Rebutted". The New York Times. October 18, 1974.

- ↑ Orcutt, Guy H. (1990). "From engineering to microsimulation : An autobiographical reflection". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 14 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(90)90038-F.

- ↑ Toffoli, Tommaso; Margolus, Norman (1987). Cellular automata machines: a new environment for modeling. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://archive.org/details/cellularautomata00toff.

- ↑ Gilbert, Nigel (1997). "A simulation of the structure of academic science". Sociological Research Online. 2 (2): 1–15. doi:10.5153/sro.85. Archived from the original on 1998-05-24. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Axelrod, Robert; Hamilton, William D. (March 27, 1981). "The Evolution of Cooperation". Science. 211 (4489): 1390–1396. Bibcode:1981Sci...211.1390A. doi:10.1126/science.7466396. PMID 7466396.

- ↑ Freeman, Linton C. (2004). The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Vancouver, BC: Empirical Press.

- ↑ Freeman, Linton C. (2004). The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Vancouver, BC: Empirical Press.

- ↑ Lazer, David; Pentland, Alex; Adamic, L; Aral, S; Barabasi, AL; Brewer, D; Christakis, N; Contractor, N; et al. (February 6, 2009). "Life in the network: the coming age of computational social science". Science. 323 (5915): 721–723. doi:10.1126/science.1167742. PMC 2745217. PMID 19197046.

- ↑ Srivastava, Jaideep; Cooley, Robert; Deshpande, Mukund; Tan, Pang-Ning (2000). "Web usage mining: discovery and applications of usage patterns from Web data". Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 1 (2): 12–23. doi:10.1145/846183.846188.

- ↑ Brin, Sergey; Page, Lawrence (April 1998). "The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine". Computer Networks and ISDN Systems. 30 (1–7): 107–117. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.115.5930. doi:10.1016/S0169-7552(98)00110-X.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 S Sudhahar; GA Veltri; N Cristianini (2015). "Automated analysis of the US presidential elections using Big Data and network analysis". Big Data & Society. 2 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1177/2053951715572916.

- ↑ S Sudhahar; G De Fazio; R Franzosi; N Cristianini (2013). "Network analysis of narrative content in large corpora" (PDF). Natural Language Engineering. 21 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1017/S1351324913000247.

- ↑ Franzosi, Roberto (2010). Quantitative Narrative Analysis. Emory University.

- ↑ S Sudhahar; G De Fazio; R Franzosi; N Cristianini (2013). "Network analysis of narrative content in large corpora" (PDF). Natural Language Engineering. 21 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1017/S1351324913000247.

- ↑ Franzosi, Roberto (2010). Quantitative Narrative Analysis. Emory University.

- ↑ I. Flaounas; M. Turchi; O. Ali; N. Fyson; T. De Bie; N. Mosdell; J. Lewis; N. Cristianini (2010). "The Structure of EU Mediasphere" (PDF). PLOS One. 5 (12): e14243. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514243F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014243. PMC 2999531. PMID 21170383.

- ↑ V Lampos; N Cristianini (2012). "Nowcasting Events from the Social Web with Statistical Learning" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. 3 (4): 72. doi:10.1145/2337542.2337557.

- ↑ I. Flaounas; O. Ali; M. Turchi; T Snowsill; F Nicart; T De Bie; N Cristianini (2011). NOAM: news outlets analysis and monitoring system (PDF). Proc. of the 2011 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data. doi:10.1145/1989323.1989474.

- ↑ N Cristianini (2011). "Automatic Discovery of Patterns in Media Content". Combinatorial Pattern Matching. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 6661. pp. 2–13. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-21458-5_2. ISBN 978-3-642-21457-8.

- ↑ Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Sudhahar, Saatviga; Thompson, James; Lewis, Justin; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello (2017-01-09). "Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in English). 114 (4): E457–E465. doi:10.1073/pnas.1606380114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5278459. PMID 28069962.

- ↑ I. Flaounas; O. Ali; M. Turchi; T. Lansdall-Welfare; T. De Bie; N. Mosdell; J. Lewis; N. Cristianini (2012). "Research methods in the age of digital journalism". Digital Journalism. 1: 102–116. doi:10.1080/21670811.2012.714928.

- ↑ T Lansdall-Welfare; V Lampos; N Cristianini. Effects of the Recession on Public Mood in the UK (PDF). Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on World Wide Web. Mining Social Network Dynamics (MSND) session on Social Media Applications. New York, NY, USA. pp. 1221–1226. doi:10.1145/2187980.2188264.

- ↑ Dzogang, Fabon; Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello (2016-11-08). "Discovering Periodic Patterns in Historical News". PLOS One. 11 (11): e0165736. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1165736D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165736. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5100883. PMID 27824911.

- ↑ Seasonal Fluctuations in Collective Mood Revealed by Wikipedia Searches and Twitter Posts F Dzogang, T Lansdall-Welfare, N Cristianini - 2016 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Workshop on Data Mining in Human Activity Analysis

- ↑ I. Flaounas; M. Turchi; O. Ali; N. Fyson; T. De Bie; N. Mosdell; J. Lewis; N. Cristianini (2010). "The Structure of EU Mediasphere" (PDF). PLOS One. 5 (12): e14243. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514243F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014243. PMC 2999531. PMID 21170383.

- ↑ V Lampos; N Cristianini (2012). "Nowcasting Events from the Social Web with Statistical Learning" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. 3 (4): 72. doi:10.1145/2337542.2337557.

- ↑ I. Flaounas; O. Ali; M. Turchi; T Snowsill; F Nicart; T De Bie; N Cristianini (2011). NOAM: news outlets analysis and monitoring system (PDF). Proc. of the 2011 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data. doi:10.1145/1989323.1989474.

- ↑ N Cristianini (2011). "Automatic Discovery of Patterns in Media Content". Combinatorial Pattern Matching. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 6661. pp. 2–13. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-21458-5_2. ISBN 978-3-642-21457-8.

- ↑ Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Sudhahar, Saatviga; Thompson, James; Lewis, Justin; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello (2017-01-09). "Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in English). 114 (4): E457–E465. doi:10.1073/pnas.1606380114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5278459. PMID 28069962.

- ↑ I. Flaounas; O. Ali; M. Turchi; T. Lansdall-Welfare; T. De Bie; N. Mosdell; J. Lewis; N. Cristianini (2012). "Research methods in the age of digital journalism". Digital Journalism. 1: 102–116. doi:10.1080/21670811.2012.714928.

- ↑ T Lansdall-Welfare; V Lampos; N Cristianini. Effects of the Recession on Public Mood in the UK (PDF). Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on World Wide Web. Mining Social Network Dynamics (MSND) session on Social Media Applications. New York, NY, USA. pp. 1221–1226. doi:10.1145/2187980.2188264.

- ↑ Dzogang, Fabon; Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello (2016-11-08). "Discovering Periodic Patterns in Historical News". PLOS One. 11 (11): e0165736. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1165736D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165736. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5100883. PMID 27824911.

- ↑ Seasonal Fluctuations in Collective Mood Revealed by Wikipedia Searches and Twitter Posts F Dzogang, T Lansdall-Welfare, N Cristianini - 2016 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Workshop on Data Mining in Human Activity Analysis

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Conte, Rosaria, et al. "Manifesto of computational social science." The European Physical Journal Special Topics 214.1 (2012): 325-346.

- ↑ Egu´ıluz, V. M.; Zimmermann, M. G.; Cela-Conde, C. J.; San Miguel, M. "American Journal of Sociology" (2005): 110, 977.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Sichman, J. S.; Conte, R. "Computational & Mathematical Organization Theory" (2002): 8(2).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Ehrhardt, G.; Marsili, M.; Vega-Redondo, F. "Physical Review E" (2006): 74(3).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Billari, Francesco C. Agent-based computational modelling: applications in demography, social, economic and environmental sciences. Taylor & Francis, 2006.

- ↑ Centola, D.; Gonz´alez-Avella, J. C.; Egu´ıluz, V. M.; San Miguel, M. "Journal of Conflict Resolution" (2007): 51.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Weisberg, Michael. When less is more: Tradeoffs and idealization in model building. Diss. Stanford University, 2003.

- ↑ Epstein, Joshua M. Generative social science: Studies in agent-based computational modeling. Princeton University Press, 2006.

- ↑ Gray, Russell D.; Greenhill, Simon J.; Jordan, Fiona M.; Gomes-Ng, Stephanie; Bibiko, Hans-Jörg; Blasi, Damián E.; Botero, Carlos A.; Bowern, Claire (2016). "D-PLACE: A Global Database of Cultural, Linguistic and Environmental Diversity". PLoS ONE. 11 (7).

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help)Authors list列表中的|first1=缺少|last1=(帮助) - ↑ Peter N. Peregrine, Atlas of Cultural Evolution, World Cultures 14(1), 2003

- ↑ "eHRAF Archaeology". Human Relations Area Files.

- ↑ "eHRAF World Cultures". Human Relations Area Files.

- ↑ Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Sudhahar, Saatviga; Thompson, James; Lewis, Justin; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello (2017-01-09). "Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in English): 201606380. doi:10.1073/pnas.1606380114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 28069962.

- ↑ Dzogang, Fabon; Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello (2016-11-08). "Discovering Periodic Patterns in Historical News". PLOS ONE. 11 (11): e0165736. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165736. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5100883. PMID 27824911.

- ↑ Seasonal Fluctuations in Collective Mood Revealed by Wikipedia Searches and Twitter Posts F Dzogang, T Lansdall-Welfare, N Cristianini - 2016 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Workshop on Data Mining in Human Activity Analysis

External links

- On-line book "Simulation for the Social Scientist" by Nigel Gilbert and Klaus G. Troitzsch, 1999, second edition 2005

- Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation

- Agent based models for social networks, interactive java applets

- Sociology and Complexity Science Website

外部链接

外部链接

- PAAA: Pan-Asian Association for Agent-based Approach in Social Systems Sciences

- CSSSA: Computational Social Science Society of the Americas

- "Life in the network: the coming age of computational social science". Retrieved June 10, 2015.

Category:Social sciences

类别: 社会科学

Category:Computational science

类别: 计算科学

Category:Computational fields of study

类别: 研究的计算领域

This page was moved from wikipedia:en:Computational social science. Its edit history can be viewed at 计算社会科学/edithistory

- CS1 English-language sources (en)

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1 errors: missing name

- 引文格式1错误:缺少作者或编者

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2017

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Social sciences

- Computational science

- Computational fields of study

- Computational social science

- 待整理页面