随机过程

在概率论及相关领域中,随机过程 stochastic process(或random process)是一个数学对象,通常被定义为随机变量的集合。给出对一个随机过程的解释,该过程表示某个系统随机的数值随时间的变化,例如细菌种群的增长,电流由于热噪声而波动,或者一个气体分子的运动。[1][4][5][6]随机过程被广泛用作以随机方式变化的系统和现象的数学模型。它们在许多学科都有应用,比如生物学[7],化学 [8] 生态学,[9] 神经科学[10], 物理学[11], 图像处理, 信号处理,[12] 控制理论, [13] 信息论,[14] 计算机科学,[15] 密码学[16] 和 电信学.[17] 此外,金融市场中看似随机的变化促进了随机过程在金融领域的广泛应用。[18][19][20]

应用和现象研究反过来又启发了新随机过程的提出。这种随机过程的例子包括维纳过程(Wiener process)或布朗运动过程(Brownian motion process,“布朗运动”可以指物理过程,也被称为“布朗运动”,以及随机过程,一个数学对象,但为了避免歧义,本文使用“布朗运动过程”或“维纳过程”来表示后者,其风格类似于:例如吉赫曼和斯科罗霍德 [21] 或罗森布拉特[22])使用路易斯·巴切勒来研究巴黎证券交易所的价格变化,[23] 以及爱尔朗使用的泊松过程来研究某段时间内拨出的电话号码。[24]这两个随机过程被认为是随机过程理论中最重要和最核心的,[1][4][25] 并且被巴切勒和爱尔朗先后于不同的环境和国家多次被独立地发现[23][26]。

随机函数 Random function这个术语也用来指随机或随机过程,[27][28] 因为随机过程也可以被解释为函数空间中的随机元素。[29][30]stochastic和random process可以互换使用,通常没有专门的数学空间用于索引随机变量。[29][31]但是,当随机变量被整数或实数的一个区间索引时,通常使用这两个术语。[5][31]如果随机变量被笛卡尔平面或某些高维欧几里得空间索引,那么随机变量的集合通常被称为随机场 random field。[5][32]随机过程的值并不总是数字,也可以是向量或其他数学对象。[5][30]

根据随机过程的数学性质,随机过程可以分为不同的类别,包括随机游走,[33] 鞅(概率论),[34] 马尔可夫过程,[35] 莱维过程,[36] 高斯过程,[37] 随机场,[38] 更新过程和分支过程[39]。随机过程的研究使用了概率、微积分、线性代数、集合论的数学知识和技术,以及拓扑学[40][41][42]和数学分析的分支,如实分析、测量理论、傅立叶分析和泛函分析。随机过程理论是对数学的重要贡献[43],不论关于理论还是应用,它都是活跃的研究主题。[44][45][46]

简介

随机过程可以被定义为随机变量的集合,这些随机变量由一些数学集合构成索引,这意味着随机过程中的每个随机变量都与集合中的一个元素唯一关联。[4][5]用于索引随机变量的集合称为“索引集”。从历史上看,索引集是实数的一些子集,例如自然数,为索引集提供了对时间的解释。[1] 集合中的每个随机变量都取值于相同的数学空间中,称为“状态空间(state space)”。例如,这个状态空间可以是整数、实数或维欧几里德空间。[1] 增量是随机过程在两个索引值之间变化的量,通常被解释为两个时间点。[47][48]由于随机性,随机过程可以有许多结果,随机过程的单个结果被称为“抽样函数”或“实现”。[30][49]

分类

随机过程可以用不同的方法进行分类,例如,根据其状态空间、索引集或随机变量之间的相关性。一种常见的分类方法是通过索引集和状态空间的基数进行分类。[50][51][52]

当解释为时间时,如果随机过程的指标集有有限个或可数个元素,例如有限的一组数、一组整数或自然数,那么随机过程被认为在离散时间域上[53][54] 。如果索引集是实数上的某个区间,则时间被称为连续时间。这两类随机过程分别被称为离散时间随机过程和连续时间随机过程[47][55][56]。离散时间随机过程被认为更容易研究,因为连续时间过程需要更先进的数学技术和知识,特别当索引集不可数时。[57][58] 如果索引集是整数或整数的子集,则随机过程也可以称为随机序列 random sequence。[54]

如果状态空间是整数或自然数,则随机过程称为“离散随机过程”或“整值随机过程”。如果状态空间是实数,则随机过程被称为“实值随机过程”或“具有连续状态空间的过程”。如果状态空间是[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-维欧几里德空间,则随机过程称为[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-“维向量过程”或[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]—“向量过程”。[59][51]

词源学

在英语中,“随机”一词最初用作形容词,其定义是“与推测有关”,源于一个希腊语词,意思是“瞄准一个目标,猜测”,而牛津英语词典将1662年作为其最早出现的年份。[60]雅各布·伯努利 Jakob Bernoulli在他关于概率的著作《猜想的艺术》(Ars conquectandi)中使用了“猜想的艺术或随机的艺术”(“Ars Conjectandi sive Stochastice”)这个短语,该著作最初于1713年以拉丁文出版。[61]在提到伯努利时,这一短语被拉迪斯劳斯-博特凯维茨 Ladislaus Bortkiewicz 使用,他在1917用德语stochastic表示“随机”的意思。[62]术语“随机过程”最早出现在1934年约瑟夫-杜布(Joseph Doob)1934年的一篇论文中。[60] 对于该术语和明确的数学定义,杜布引用了另一篇1934年的论文,其中亚历山大-金钦 Aleksandr Khinchin用德语使用了"stochastischer Prozeß ”一词,[63][64]尽管这个德语术语在早些时候就被使用过,例如,安德烈-科尔莫戈罗夫 Andrei Kolmogorov在1931年就使用了它。[65]

根据牛津英语词典的研究,英语中和随机含义相同的这个词的早期出现,可以追溯到16世纪,而早期记录的类似用法开始于14世纪,它是一个名词,意思是“浮躁、极速、力量或暴力(在骑马、奔跑、惊人等等)”。这个单词本身来自中世纪法语单词,意思是“速度,匆忙” ,它可能来源于法语动词,意思是“奔跑”或“疾驰”。随机(random)过程这个术语的第一次书面出现早于随机(stochastic)过程,牛津英语词典也把它作为同义词,并在弗朗西斯·埃奇沃思1888年发表的一篇文章中使用。

根据《牛津英语词典》,“随机”一词在英语中的早期出现及其目前的含义——即与机会或运气有关,可以追溯到16世纪,而更早的使用记录始于14世纪,是一个名词,意思是 "急躁、巨大的速度、力量或暴力(在骑马、跑步、击球等方面)"。这个词本身来自一个中古法语单词,意思是 "速度、匆忙",它可能是从法语动词“奔跑”或“飞奔”衍生而来。随机过程(random process)一词的首次书面出现早于随机过程(stochastic process),《牛津英语词典》也将其作为同义词,并被弗朗西斯·艾其沃斯 Francis Edgeworth 于1888年发表的一篇文章中使用。[66]

术语

随机过程的定义各不相同[67] ,但是传统上随机过程被定义为由某个集合索引的随机变量的集族[68][69]。术语“随机(random)过程”和“随机(stochastic)过程”被视为同义词,可以互换使用,而无需精确指定索引集。[29][31][32][70][71][72]。 "集合"[30][70] 和"族"[4][73]都会使用,而有时则用 "参数集"[30] 或 "参数空间"[32]来代替 "索引集"。

术语“随机函数”也用于指代随机过程(stochastic process)或随机过程(random process),[5][74][75]尽管有时它只在随机过程取实值时使用。[30][73]当索引集是实数以外的数学空间时,也使用这个术语[5][76],而当索引集被解释为时间时,通常使用“随机过程”(stochastic process)和“随机过程”(random process),[5][76][77]另外当索引集是[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-维欧几里德空间[math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^n }[/math]或流形时,会用随机场这一术语。[5][30][32]

记号

随机过程可以用[math]\displaystyle{ \{X(t)\}_{t\in T} }[/math],[55] [math]\displaystyle{ \{X_t\}_{t\in T} }[/math],[69] [math]\displaystyle{ \{X_t\} }[/math][78]或简单地称为[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]或[math]\displaystyle{ X(t) }[/math],尽管[math]\displaystyle{ X(t) }[/math]被视为函数表示法的滥用。[79] 比如, [math]\displaystyle{ X(t) }[/math] 或 [math]\displaystyle{ X_t }[/math]表示具有索引[math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math]的随机变量,而不是整个随机过程。[78]如果索引集是[math]\displaystyle{ T=[0,\infty) }[/math],那么我们可以这样写,例如用[math]\displaystyle{ (X_t , t \geq 0) }[/math]来表示随机过程。[31]

示例

伯努利过程

最简单的随机过程之一是伯努利过程,[80]它是独立同分布随机变量的序列,其中每个随机变量取值1或0,比如概率[math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]的值为1,概率[math]\displaystyle{ 1-p }[/math]为零。这个过程可以与反复投一枚硬币关联,其中正面的概率为[math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math],其值为1,而反面的值为零。[81]换句话说,伯努利过程是一系列独立同分布的伯努利随机变量,[82]每一次抛硬币都是伯努利试验的一个例子。[83]

随机游走

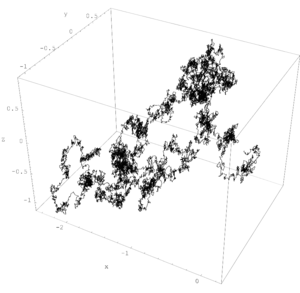

随机游走这样一类随机过程,通常定义为欧几里德空间中独立同分布的随机变量或者或随机向量的和,因此它们是在离散时间上变化的过程。[84][85][86][87][88]但是有些人也使用这个术语来指代在连续时间上变化的过程,[89]尤其是金融中使用的维纳过程,这导致了一些误解,从而招来了一些批评。[90]还有其他各种类型的随机游走,它们的状态空间可以是其他数学对象,例如格和群,一般来说,它们都是被充分研究的,在不同的学科中有许多应用。[91][92]

随机游走的一个经典例子被称为“简单随机游走”,它是一个离散时间上的随机过程,以整数为状态空间,基于伯努利过程,其中每个伯努利变量取+1或-1。换言之,简单随机游走发生在整数上,其值要么随概率[math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]增加1,要么随着概率[math]\displaystyle{ 1-p }[/math]而减小1,因此这种随机游动的指标集是自然数,而其状态空间是整数。如果[math]\displaystyle{ p=0.5 }[/math],这种随机游动称为对称随机游走。[93][94]

维纳过程

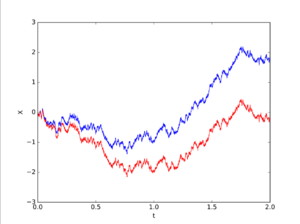

维纳过程是一个具有平稳独立增量并且基于增量大小呈正态分布的随机过程。[2][95]维纳过程是以诺伯特-维纳命名的,他证明了它的数学存在性,但是这个过程也被称为布朗运动过程或布朗运动,因为它和液体中的布朗运动有历史渊源。[96][97][97][98]

维纳过程在概率论中起着核心作用,它通常被认为是最重要和最值得研究的随机过程,并与其他随机过程联系在一起[1][2][3][99][100][101][102]。它的索引集和状态空间分别是非负数和实数,所以它既有连续索引集又有状态空间[103]但该过程可以被更广泛地定义,所以它的状态空间可以是n维欧几里德空间。[92][100][104]如果任何增量的平均值为零,那么产生的维纳或布朗运动过程被称为具有零漂移。如果任意两个时间点的增量的平均值等于时间差乘以某个常实数[math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math],那么由此产生的随机过程被称为具有漂移[math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math]。[105][106][107]

几乎可以肯定,维纳过程的样本路径处处连续,但无处可微。它可以看作是简单随机游走的一个连续版本。[48][106]该过程作为其他随机过程的(如某些随机游走的缩放)数学极限而出现,[108][109]这是唐斯克定理或不变性原理的主题,也被称为函数中心极限定理。[110][111][112]

维纳过程是一些重要的随机过程家族的成员,包括马尔可夫过程,莱维过程和高斯过程。[2][48]该过程也有许多应用,是随机微积分中使用的主要随机过程。[113][114]它在量化金融中起着核心作用,[115][116]例如,它被用于布莱克-舒尔斯(Black-Scholes-Merton)模型。[117]该过程也被用于不同的领域,包括大多数自然科学以及社会科学的一些分支,作为各种随机现象的数学模型。[3][118][119]

泊松过程

泊松过程是一个随机过程,有不同的形式和定义。[120][121]它可以定义为一个计数过程,它是一个随机过程,表示某个时间点或事件的随机数量。在从零到某个给定时间区间内的过程点的数目是一个泊松随机变量,它取决于该时间和某个参数。该过程以自然数为状态空间,非负数为索引集。此过程也称为泊松计数过程,因为它可以被解释为计数过程的一个示例。[122]

如果一个泊松过程是用一个正的常数定义的,那么这个过程称为齐次泊松过程。[120][123]齐次泊松过程泊松过程是马尔科夫过程和莱维过程等重要随机过程类别中的一员[48]

齐次泊松过程可以用不同的方法定义和推广。它的指标集可以定义为实数,这个随机过程也被称为平稳泊松过程[124][125]如果泊松过程的参数常数被某个非负可积函数的[math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math]代替,则得到的过程称为非齐次或非同质泊松过程,其中过程点的平均密度不再是常数。[126]作为排队论中的一个基本过程,泊松过程是数学模型里的一个重要过程,它在某些时间窗口内随机发生的事件模型中得到应用。[127][128]

在实数上定义的泊松过程可以被解释为随机过程[48][129]以及其他随机对象。[130][131]但是它也可以被定义在[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]维欧几里德空间或其他数学空间上,[132]在那儿它通常被解释为随机集或随机计数度量,而不是随机过程。[130][131]在这种情况下,泊松过程,也称为泊松点过程,是概率论中最重要的对象之一,既有应用上的原因,也有理论上的原因。[24][133]但有人指出,泊松过程并没有得到应有的重视,部分原因是它经常被认为只是在实数上,而不是在其他数学空间中。[133][134]

定义

随机过程 Stochastic process

随机过程被定义为在一个公共概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega, \mathcal{F}, P) }[/math]上定义的随机变量集合,其中[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math] 是样本空间,[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math]是一个[math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math]-代数,[math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]是概率测度;而随机变量,由某个集合[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]索引,所有值都取同一个数学空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math],对于某些[math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math]-代数[math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math][30]

换言之,对于给定的概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega,\mathcal{F},P) }[/math]和可测空间[math]\displaystyle{ (S,Sigma) }[/math],随机过程是一个值为[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]的随机变量的集合,可以写成:[80]

历史上,在许多自然科学问题中,一个点[math]\displaystyle{ t\in T }[/math] 具有时间的意义,因此,[math]\displaystyle{ X(t) }[/math]表示是一个在时间[math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math]的随机变量。[135]随机过程也可以写成[math]\displaystyle{ \{X(t,omega):t\ in t\} }[/math]来反映它实际上是两个变量的函数,[math]\displaystyle{ t\in t }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ \omega\in\omega }[/math][30][136]

还有其他方法可以考虑随机过程,上面的定义被认为是传统的。[68][69]例如,一个随机过程可以解释或定义为一个[math]\displaystyle{ S^T }[/math]值的随机变量,其中[math]\displaystyle{ S^T }[/math]是所有可能的[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]-值函数的空间T</math>从集合[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]到空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]。[29][68]

索引集

集合[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]称为“索引集”[4][50]或“参数集”[30][137]。通常,这个集合是实数的一个子集,例如自然数或一个区间,使集合[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]能够解释时间。[1]除了这些集合,索引集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]可以是其他线性有序集或更一般的数学集,[1][53]例如笛卡尔平面[math]\displaystyle{ R^2 }[/math]或[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]维欧几里得空间,其中t中的元素可以表示空间中的一个点。[47][138]但一般情况下,当索引集有序时,随机过程可以得到更多的结果和定理。[139]

状态空间

随机过程的数学空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]称为其“状态空间”。这个数学空间可以用整数、实数、[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]维欧几里得空间、复杂平面或更抽象的数学空间来定义。状态空间是用反映随机过程可以采用的不同值的元素来定义的进程。[1][5][30][50][55]

样本函数

样本函数是随机过程的单个结果,因此,它是由随机过程中每个随机变量的一个可能值构成的。[30][140]更准确地说,如果[math]\displaystyle{ \{X(t,omega):t\in t\} }[/math]是一个随机过程,那么对于任何点[math]\displaystyle{ \omega\in\omega }[/math],映射

称为样本函数,称为“实现”,或者,特别是当[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]被解释为时间时,随机过程的“样本路径”[math]\displaystyle{ \{X(T,omega):T\in T\} }[/math]。[49]这意味着对于一个固定的[math]\displaystyle{ \omega\in\omega }[/math],存在一个将索引集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]映射到状态空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math][30] 的示例函数的其他名称随机过程包括“轨迹”、“路径函数”[141]或“路径”.[142]

增量

随机过程的增量是同一随机过程的两个随机变量之间的差值。对于一个指数集可以解释为时间的随机过程,增量是随机过程在某个时间段内的变化量。例如,如果[math]\displaystyle{ \{X(t):t\in t\} }[/math] 是具有状态空间的随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]且索引集[math]\displaystyle{ T=[0,\infty) }[/math]中的任意两个非负数[math]\displaystyle{ t_1\in [0,\infty) }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ t_2\in [0,\infty) }[/math]且[math]\displaystyle{ t_1\leq t_2 }[/math],差异[math]\displaystyle{ X{tu 2}-X{t_1} }[/math]是一个称为增量的[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]值随机变量。[47][48]当对增量感兴趣时,通常状态空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]是实数或自然数,但它可以是[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]维欧几里德空间或更抽象的空间,如巴拿赫空间 。[48]

进一步定义

定律

对于定义在概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega,\mathcal{F},P) }[/math]上的随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X\colon\Omega\rightarrow S^T }[/math],随机过程X</math>的定律被定义为前推度量 Pushforward measure:

其中[math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math]是一个概率度量,符号[math]\displaystyle{ \circ }[/math]表示函数组合,[math]\displaystyle{ X^{-1} }[/math]是可测量函数的前映像,或者等价地,[math]\displaystyle{ S^T }[/math]值随机变量[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math],其中[math]\displaystyle{ S^T }[/math]是[math]\displaystyle{ t\in T }[/math]中所有可能的[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]值函数的空间,所以随机过程的规律就是一个概率测度。[29][68][143][144]

对于[math]\displaystyle{ S^T }[/math]的可测子集[math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math],预图像[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]给出

所以a[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]定律可以写成:[145]

随机过程或随机变量的规律也被称为“概率定律 probability law”,“概率分布 probability distribution”,或“分布”。[135][143][146][147][148]

有限维概率分布

对于随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math],其“有限维分布”定义为:

这项措施[math]\displaystyle{ \mu_{t_1,..,t_n} }[/math]是随机向量的联合分布 [math]\displaystyle{ (X({t_1}),\dots, X({t_n})) }[/math];它可以被视为法律的“投影”[math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math]到一个有限子集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]。[29][149]

对于[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]级笛卡尔幂[math]\displaystyle{ S^n=S\times\dots \times S }[/math]的任何可测子集[math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]的有限维分布可以写成:[30]

随机过程的有限维分布满足两个称为一致性条件的数学条件。[56]

稳定性

“稳定性”是当随机过程的所有随机变量都是相同分布时随机过程所具有的数学性质。换言之,如果[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]是一个平稳随机过程,那么对于任何[math]\displaystyle{ t\in T }[/math],随机变量[math]\displaystyle{ X_t }[/math]具有相同的分布,这意味着对于任何一组[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]索引集值[math]\displaystyle{ t_1,\dots, t_n }[/math]而言,对应的[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]随机变量

它们都有相同的概率分布。平稳随机过程的指标集通常被解释为时间,因此可以是整数或实数。[150][151] 但对于点过程和随机场也存在平稳性的概念,其中指标集不被解释为时间。[150][152][153]

当指标集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]可以解释为时间时,如果随机过程的有限维分布在时间平移下是不变的,则称其为平稳过程。这种随机过程可以用来描述处于稳态的物理系统,但是仍然会经历随机波动。[150]平稳性背后的直觉是,随着时间的推移,平稳随机过程的分布保持不变。[154]只有当随机变量相同分布时,一系列随机变量才会形成平稳随机过程。[150]

具有上述平稳性定义的随机过程有时被称为严格平稳的,但也有其他形式的平稳性。一个例子是当离散时间或连续时间随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]被称为广义平稳时,那么这个过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math],有一个有限的第二时刻对于所有[math]\displaystyle{ t\in T }[/math]和两个随机变量的协方差 [math]\displaystyle{ X_t }[/math] 和 [math]\displaystyle{ X_{t+h} }[/math] 只取决于在[math]\displaystyle{ t\in T }[/math]时的数值[math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math][154][155] 辛钦介绍了“广义平稳性”的相关概念,其他名称包括“协方差平稳性”或“广义平稳性”。[155][156]

过滤

过滤是定义在某个概率空间中的西格玛代数的递增序列,它具有某种总阶关系的索引集,例如在索引集是实数的某个子集的情况下。更正式地说,如果一个随机过程有一个具有总阶数的索引集,那么在概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega, \mathcal{F}, P) }[/math]上的过滤[math]\displaystyle{ \{\mathcal{F}_t\}_{t\in T} }[/math] 是一个西格玛代数族,使得[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F}_s \subseteq \mathcal{F}_t \subseteq \mathcal{F} }[/math]对所有[math]\displaystyle{ s \leq t }[/math],其中[math]\displaystyle{ t, s\in T }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ \leq }[/math]表示指标集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]的总阶[50]。通过过滤的概念,可以研究[math]\displaystyle{ t\in T }[/math]中随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X_t }[/math]所包含的信息量,这可以解释为时间[math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math][50][157]过滤背后的直觉是,随着时间的流逝,关于[math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math]的更多信息是已知的或可用的,这些信息可以在[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F}t }[/math]中获得,使[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math]的分区越来越细。[158][159]

修正

随机过程的“修正”是另一个随机过程,它与原始随机过程密切相关。更确切地说,一个随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math],与另一个随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] 具有相同的索引集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]、集空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]和概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega,{\cal F},P) }[/math]具有相同的索引集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]、集空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]和概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega,{\cal F},P) }[/math],被称为[math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math]的修改,如果对所有[math]\displaystyle{ t\in T }[/math]有

持有。两个相互修正的随机过程具有相同的有限维法则[160],它们被称为“随机等价”或“等价物”[161]

除了修改,也可以使用“版本”一词,[152][162][163][164]然而,当两个随机过程具有相同的有限维分布,但它们可能定义在不同的概率空间上时,一些作者使用版本一词。因此在后一种意义上,两个相互修改的过程也是彼此的版本,但不是相反。[165][143] .

如果一个连续时间的实值随机过程在其增量上满足一定的矩条件,则柯尔莫哥洛夫连续性定理指出,该过程存在一个修正,其具有概率为1的连续样本路径,所以这个随机过程有一个连续的修改或版本[163][164][166]。该定理也可以推广到随机场,所以索引集是[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-维欧几里德空间[167]以及以度量空间作为其状态空间的随机过程。[168]

难区分性

两个随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math]定义在同一概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega,\mathcal{F},P) }[/math]上,具有相同的索引集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]和集空间[math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]上的两个随机过程如果

成立,则称为“难以区分的”。[143][160]如果两个[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math]是相互修改的,几乎肯定是连续的,那么[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math]是无法区分的。[169]

可分性

“可分性”是随机过程的一种性质,它基于与概率测度有关的指标集。假设该属性是为了使具有不可计数索引集的随机过程或随机场的函数能够形成随机变量。要使一个随机过程是可分离的,除了其他条件外,它的索引集必须是一个可分离的空间{efn |术语 "可分离 "在这里出现了两次,有两种不同的含义,其中第一种含义来自概率,第二种来自拓扑学和分析。要使一个随机过程是可分离的(在概率意义上),其索引集必须是一个可分离的空间(在拓扑学或分析学意义上),此外还有其他条件。[137]}},这意味着索引集有一个稠密可数子集。[152][170]

更精确地说,具有概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega,{\cal F},P) }[/math]的实值连续时间随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]是可分离的,如果它的指数集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]有一个稠密的可数子集[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega_0 \subset \Omega }[/math],因此<[math]\displaystyle{ P(\Omega_0)=0 }[/math],这样对于每个开集[math]\displaystyle{ G\subset T }[/math]和每个闭集[math]\displaystyle{ F\subset \textstyle R =(-\infty,\infty) }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ \{ X_t \in F \text{ for all } t \in G\cap U\} }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ \{ X_t \in F \text{ for all } t \in G\} }[/math]这两个事件最多在[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega_0 }[/math]的一个子集上不同。[171][172][173]

可分性的定义(连续时间实值随机过程的可分性定义可以用其他方式表述[174][175])也可用于其他索引集和状态空间,[176]例如在随机场的情况下,索引集和状态空间可以是[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]维欧几里德空间。[32][152]

随机过程可分性的概念是由约瑟夫-杜布(Joseph Doob)[170]提出的。可分性的基本思想是使指标集的可数点集决定随机过程的性质。[174]任何具有可数索引集的随机过程都已经满足可分离性条件,所以离散时间随机过程总是可分离的。 [177]杜布的一个定理,有时被称为杜布可分性定理,指出任何实值的连续时间随机过程都有一个可分离的修改。[170][172][178]这个定理的版本也存在于具有实数之外的索引集和状态空间的更一般的随机过程。[137]

独立性

两个在相同的概率空间[math]\displaystyle{ (\Omega,\mathcal{F},P) }[/math]上定义,具有相同索引集[math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]的随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math]被称为“相互独立”,如果对于所有[math]\displaystyle{ n \in \mathbb{N} }[/math],以及每个特定的[math]\displaystyle{ t_1,\ldots,t_n \in T }[/math],随机向量[math]\displaystyle{ \left( X(t_1),\ldots,X(t_n) \right) }[/math] 和[math]\displaystyle{ \left( Y(t_1),\ldots,Y(t_n) \right) }[/math]是独立的。[179]

不相关

两个随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ \left\{X_t\right\} }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ \left\{Y_t\right\} }[/math] 称为“不相关的”的,如果它们的互协方差[math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{K}_{\mathbf{X}\mathbf{Y}}(t_1,t_2) = \operatorname{E} \left[ \left( X(t_1)- \mu_X(t_1) \right) \left( Y(t_2)- \mu_Y(t_2) \right) \right] }[/math]始终为零。[180]最后:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left\{X_t\right\},\left\{Y_t\right\} \text{ uncorrelated} \quad \iff \quad \operatorname{K}_{\mathbf{X}\mathbf{Y}}(t_1,t_2) = 0 \quad \forall t_1,t_2 }[/math].

独立意味着不相关

如果两个随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math]是独立的,那么它们也是不相关的

正交性

如果两个随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ \left\{X_t\right\} }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ \left\{Y_t\right\} }[/math]的互相关[math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{R}_{\mathbf{X}\mathbf{Y}}(t_1,t_2) = \operatorname{E}[X(t_1) \overline{Y(t_2)}] }[/math]一直为0,则称为“正交”,形式为[180]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left\{X_t\right\},\left\{Y_t\right\} \text{ orthogonal} \quad \iff \quad \operatorname{R}_{\mathbf{X}\mathbf{Y}}(t_1,t_2) = 0 \quad \forall t_1,t_2 }[/math].

斯科罗霍德空间

斯科罗霍德空间(Skorokhod space或Skorohod space)是所有右连续左极限的函数的数学空间。这些函数定义在实数的某个区间上,例如[math]\displaystyle{ [0,1] }[/math]或[math]\displaystyle{ [0,\infty) }[/math],取实数或度量空间上的值。[181][182][183]这样的函数被称为右连左极(cádLag或cadlag)函数,这是法语表达式“continue a droite,limiteégauche”的首字母缩略词,因为这些函数是右连续的,具有左极限。[181][184]由阿纳托利·斯科罗霍德(Anatoliy Skorokod)引入的斯科罗霍德函数空间,[183]通常用字母[math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math]表示,[181][182][183][184]因此函数空间也被称为空间[math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math][181][185][186]此函数空间的表示法还可以包括定义所有右连左极函数的间隔,因此,例如,[math]\displaystyle{ D[0,1] }[/math]表示在单位间隔[math]\displaystyle{ [0,1] }[/math]上的右连左极函数空间。[184][186][187]

在随机过程理论中,由于通常假定连续时间随机过程的样本函数属于一个斯科罗霍德空间,[183][185]因此经常使用斯科罗霍德函数空间。这种空间包含连续函数,它对应于维纳过程的样本函数。但是该空间也有具有不连续性的函数,这意味着具有跳跃性的随机过程的样本函数,例如在实数上的泊松过程也是该空间的成员。[186][188]

正则性

在随机过程的数学构造中,当讨论和假设随机过程的某些条件以解决可能的构造问题时,使用“正则性”这一术语。[189][190]例如,为了研究具有不可数索引集的随机过程,假设随机过程遵守某种类型的正则条件,如样本函数是连续的。[191][192]

更多示例

马尔可夫过程与链

马尔可夫过程 Markov processes 是一种随机过程,传统上是离散或连续时间的,具有马尔可夫特性,即马尔可夫过程的下一个值取决于当前值,但它有条件地独立于随机过程的前一个值。换句话说,在进程的当前状态下,进程在未来的行为是随机地独立于它在过去的行为。[193][194]

布朗运动过程和泊松过程(一维)都是马尔可夫过程的例子[195],而整数上的随机游走和赌徒破产问题是离散时间中马尔可夫过程的例子。[196][197]

马尔可夫链是一种具有离散状态空间或离散索引集(通常表示时间)的马尔可夫过程,但马尔可夫链的精确定义各不相同[198]。例如,通常将马尔可夫链定义为具有可数状态空间的离散或连续时间中的马尔可夫过程(因此不管时间的性质),[199][200][201][202]但也常将马尔可夫链定义为具有可数或连续状态空间的连续时间(因此与状态空间无关),[198]有人认为,现在倾向于使用具有离散时间的马尔可夫链的第一个定义,尽管约瑟夫-杜布(Joseph Doob)和钟开莱(Kai Lai Chung)等研究人员使用了第二种定义。[203]

马尔可夫过程是一类重要的随机过程,在许多领域有着广泛的应用。[41][204]例如,它们是一种称为马尔可夫链蒙特卡洛的一般随机模拟方法的基础,该方法用于模拟具有特定概率分布的随机对象,并在贝叶斯统计中得到应用。[205][206]

马尔可夫属性的概念最初是针对连续和离散时间的随机过程,但它也适用于其它指标集,如[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]维欧氏空间,这就导致了被称为马尔可夫随机场的随机变量集合。[207][208][209]

鞅

鞅(Martingale)是一个离散时间或连续时间的随机过程,其性质是在给定过程的当前值和所有过去值的情况下,每个未来值的条件期望值等于当前值。在离散时间中,如果此属性适用于下一个值,则它适用于所有未来值。鞅的精确数学定义需要另外两个条件,再加上过滤(filtration)的数学概念,这与随时间推移可用信息增加的直觉有关。鞅通常被定义为实值的,[210][211][157] 但他们也可以是复数或[212]或更一般的取值。[213]

对称随机游动和维纳过程(具有零漂移)分别是离散时间和连续时间中鞅的例子。[210][211]对于一串独立且同分布随机变量[math]\displaystyle{ X_1, X_2, X_3, \dots }[/math],其平均值为零。由连续部分和[math]\displaystyle{ X_1,X_1+ X_2, X_1+ X_2+X_3, \dots }[/math] 构成的随机过程是一个离散时间鞅[214]。在这一方面,离散时间鞅推广了独立随机变量的部分和的概念。[215]

鞅也可以通过应用一些适当的变换从随机过程中产生,这就是齐次泊松过程(在实数上)的情形,其结果是一个称为“补偿泊松过程”的鞅。[211]也可以从其他鞅中构建鞅。[214]例如,有基于鞅的维纳过程,形成了连续时间鞅。[210][216]

数学上的鞅形式化了公平博弈的概念,[217]它们最初是为了证明不可能赢得一场公平比赛而发展出来的。[218]但现在它们被用于概率的许多领域,这是研究它们的主要原因之一。[157][218][219]概率学中的许多问题都是通过在问题中找到鞅并加以研究而解决的。[220]在给定鞅矩的条件下,鞅会收敛,所以他们经常被用来推导收敛结果,这主要是由于鞅收敛定理。[215][221][222]

鞅在统计学中有许多应用,但有人指出,它的使用和应用在统计学领域,尤其是统计推断领域并不那么广泛。[223]他们在排队论和Palm微积分等概率论领域以及经济学[224]、金融领域[19]都有应用[225]。

莱维过程

莱维过程是一类随机过程,可以看作是连续时间中随机游走的推广。[48][226]这些过程在金融、流体力学等领域有着广泛的应用。[227][228]这些过程的主要定义特征是其静止性和独立性属性,所以它们被称为具有静止和独立增量的过程。换句话说,一个随机过程[math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]是一个莱维过程,如果对非负数[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ 0\leq t_1\leq \dots \leq t_n }[/math],当[math]\displaystyle{ n-1 }[/math]递增

它们彼此独立,每个增量的分布只取决于时间的差异。[48]

莱维过程可以被定义为状态空间是一些抽象的数学空间的,比如巴拿赫空间,但这些过程通常被定义为它们在欧几里得空间取值。索引集是非负数,所以[math]\displaystyle{I=[0,\infty )}{\displaystyle I=[0,\infty )}[/math],这给出了时间的解释。重要的随机过程,如维纳过程、齐次泊松过程(在一个维度上),以及次元都是莱维过程。

随机场

随机场是由一个[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]维欧几里德空间或流形索引的随机变量的集合。一般来说,随机场可以看作是随机过程的一个例子,其中索引集不一定是实数的子集。[32]但是有一个惯例,当索引具有两个或多个维度时,随机变量的索引集合称为随机场。[5][30][229]如果随机过程的具体定义要求索引集是实数的子集,那么随机场可以看作是随机过程的一个推广。[230]

点过程

点过程是随机分布在某些数学空间(如实数、[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]维欧几里德空间或更抽象的空间)上的点的集合。有时“点过程”一词并不可取,因为历史上“过程”一词表示某个系统在时间上的演变,因此,点过程也被称为“随机点域”。[231]对点过程有不同的解释,如随机计数度量或随机集。[232][233]一些作者将点过程和随机过程视为两个不同的对象,也就是说点过程是随机过程产生或与随机过程相关联的随机对象,[234][235]尽管有人评论说,点过程和随机过程之间的区别并不明显。[235]

另一些作者认为点过程是一个随机过程,其中过程由它所定义的基础空间(在点过程的上下文中,“状态空间”一词可以指定义点过程的空间,如实数,[236][237]它对应于随机过程中的索引集)集合来索引,如实数或[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-维的欧几里得空间。[238][239]其他随机过程,如更新和计数过程,也在点过程理论中进行了研究。[240][241]

历史 History

早期概率论 Early probability theory

概率论起源于机会博弈,它有着悠久的历史,有些游戏在几千年前就已经开始了,[242][243]但人们很少从概率的角度对其进行分析。[242][244]1654年通常被认为是概率论的诞生,当时法国数学家皮埃尔-费马和布莱斯-帕斯卡尔在一个赌博问题的激励下,就概率问题进行了书面通信。[242][245][246]但是在更早的时候,就有关于赌博游戏概率的数学工作,比如吉罗拉莫·卡尔达诺(Gerolamo Cardano)16世纪写作的“Liber de Ludo Aleae”,在他死后于1663年发表。[242][247]

继卡尔达诺之后,雅各布·伯努利(Jakob Bernoulli,也被称为James Bernoulli或Jacques Bernoulli[248])写了Ars conjuctandi,这在概率论史上被认为是重大事件。[242]伯努利的书出版于1713年,也是在他死后出版的,这本书激发了许多数学家研究概率。[242][249][250] 但是,尽管一些著名的数学家对概率论做出了贡献,比如皮埃尔-西蒙-拉普拉斯(Pierre-Simon Laplace,)、亚伯拉罕-德-莫伊夫(Abraham de Moivre)、卡尔-高斯(Carl Gauss)、西蒙-泊阿松 (Siméon Poisson)和帕夫努蒂·切比雪夫(Pafnuty Chebyshev),[251][252]大多数数学界人士直到20世纪,才认为概率论是数学的一部分(一个显著的例外是俄罗斯的圣彼得堡学派,在那里,以切比雪夫为首的数学家研究概率论[253])。[251][253][254][255]

统计力学 Statistical mechanics

在物理科学领域,科学家们在19世纪发展了统计力学学科。在这个学科中,物理系统,例如装满气体的容器,可以从数学上看作或处理为许多运动粒子的集合。尽管有些科学家(比如鲁道夫·克劳修斯(Rudolf Clausius))试图将随机性纳入统计物理学,但大部分工作没有或几乎没有随机性。[256][257]

这种情况在1859年发生了变化,当时詹姆斯·克拉克·麦克斯韦 James Clerk Maxwell对该领域做出了重大贡献,更具体地说,他提出了气体的动力学理论,假设气体粒子以随机速度向随机方向移动。[258][259]气体动力学理论和统计物理在19世纪下半叶继续发展,其工作主要由克劳修斯,路德维希·玻尔兹曼和约西亚·威拉德·吉布斯完成,这些工作后来对阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦的布朗运动数学模型产生了影响。[260]

测度论与概率论

1900年在巴黎举行的国际数学家大会上,大卫-希尔伯特(David Hilbert)提出了一份数学问题的清单,其中他的第六个问题要求对物理和概率的公理化进行数学处理。[252]大约在20世纪初,数学家们发展了测度论,这是研究函数积分的数学分支,其中两位创始人是法国数学家亨利-勒贝斯格(Henri Lebesgue)和米尔-博莱尔É(mile Borel。)1925年,另一位法国数学家P保罗·莱维(aul Lévy出)版了第一本使用测度论思想的概率论书籍。[252]

20世纪20年代,苏联的数学家们对概率论做出了重大贡献,比如谢尔盖-伯恩斯坦(Sergei Bernstein),亚历山大-辛钦(Aleksandr Khinchin,Khinchin这个名字也用英语写成(或音译成)Khintchine。[63])和安德烈-科尔莫戈罗夫(Andrei Kolmogorov)。[255] 科尔莫戈罗夫于1984年发表了他的一次尝试,为概率论提出一个基于度量理论的数学基础。[261]在20世纪30年代初,辛钦和科尔莫戈罗夫成立了概率研讨会,金-斯卢茨基(Eugene Slutsky等)、尼古拉-斯米尔诺夫(Nikolai Smirnov)等研究人员参加了这些研讨会,[262]辛钦首次给出了随机变量的数学定义,即由实数索引的一组随机变量。[63][263](Doob在引用Khinchin时,使用了“机会变量”这个词,它曾经是“随机变量”的替代词。[264])

现代概率论的诞生 Birth of modern probability theory

1933年,德烈-科尔莫戈罗夫(Andrei Kolmogorov在)德国出版了一本关于概率论基础的书,名为《概率计算的基本概念》,后来翻译成英文,1950年出版,作为概率论的基础。这本书的出版现在被广泛认为是现代概率论的诞生,从此概率论和随机过程理论成为数学的一部分。[252][255]

在科尔莫戈罗夫的书出版后,辛钦和科尔莫戈洛夫以及其他数学家如约瑟夫-杜布(Joseph Doob)、威廉-费勒(William Feller)、莫里斯-弗雷谢(Maurice Fréchet)、保罗-莱维(Paul Lévy)、沃尔夫冈-多布林(Wolfgang Doeblin)和哈拉尔-克拉梅尔(Harald Cramér)[252][255],都在概率论和随机过程方面做了进一步的基础工作,

几十年后,克拉梅尔(Cramér)把20世纪30年代称为“数学概率论的英雄时期”。[255]第二次世界大战很大程度上中断了概率论的发展。例如,大战导致费勒从瑞典迁移到美国[255],以及现在被认为是随机过程先驱的多布林的去世。[265]

二战后的随机过程

第二次世界大战后,概率论和随机过程的研究得到了数学家的更多关注,在概率论和数学的许多领域做出了重大贡献,并开创了新的领域统计学。[255][268]从20世纪40年代开始,伊藤清司(Kiyosi Itô)发表了发展随机微积分领域的论文,其中设计基于维纳或布朗运动过程的随机积分和随机微分方程。[269]

同样从20世纪40年代开始,随机过程(尤其是鞅)与数学领域的势理论之间建立了联系,角谷静夫(Shizuo Kakutani)的早期思想和后来约瑟夫(Joseph Doob)的工作都是如此。[268]在20世纪50年代尔伯特-亨特G(ilbert Hunt)完成了被创性的进一步工作,他把马尔科夫过程和势能理论联系起来,这对莱维过程的理论产生了重大影响,并使人们对用伊藤开发的方法研究马尔科夫过程产生了更多兴趣。[23][270][271]

1953年,约瑟夫-杜布(Joseph Doob)出版了《随机过程》一书,这本书对随机过程理论产生了重大影响,并强调了测度理论在概率论中的重要性。[268][267]杜布还要发展了鞅理论,后来Paul-André Meyer也作出了重大贡献。早期的工作是由谢尔盖-伯恩斯坦(Sergei Bernstein)、保罗-莱维(Paul Lévy)和让-维尔(Jean Ville)进行的,后者对随机过程采用了“鞅”一词。[272][273]鞅理论中的方法已成为解决各种概率问题的常用方法。研究马尔可夫过程的技术和理论被开发出来,然后被应用于鞅上。反之,从鞅理论中也建立了处理马尔可夫过程的方法。[268]

概率的其他领域也被发展和用于随机过程的研究,其中一个主要方法是大偏差理论。[268] 该理论在统计物理等领域有许多应用,其核心思想至少可以追溯到20世纪30年代。在20世纪60年代和70年代后期,苏联的亚历山大·温策尔(Alexander Wentzell)和美国的门罗-D-唐斯克(Monroe D.Donsker)以及斯里尼瓦萨-瓦拉丹(Srinivasa Varadhan)完成了基础工作,[274]后来瓦拉丹获得了2007年阿贝尔奖。[275]在上世纪90年代和21世纪,Schramm-Loewner演化[276]和粗略路径[143]理论被引入和发展来研究概率论中的随机过程和其他数学对象,这促使菲尔兹奖分别在2008年被授予德林-维尔纳W(endelin Werner)[277],在2014年被授予马丁-海勒(Martin Hairer)[278]。

随机过程理论仍然是研究的焦点,每年都有关于随机过程的国际会议。[44][227]

特定随机过程的发现

虽然辛钦在1930年代给出了随机过程的数学定义[279][280],但在不同的环境中已经发现了具体的随机过程,如布朗运动过程和泊松过程[281][282]。一些随机过程的族,如点过程或更新过程,有着漫长而复杂的历史,可以追溯到几个世纪前[283]。

伯努利过程

伯努利过程可以作为抛出有偏的硬币的数学模型,它可能是第一个被研究的随机过程[81]。这个过程是一连串独立的伯努利试验[284],伯努利是以杰克-伯努利(Jackob Bernoulli)的名字命名的,他用这些试验来研究机会博弈,包括克里斯蒂安-惠更斯(Christiaan Huygens)早先提出和研究的概率问题[248]。伯努利的工作,包括伯努利过程,于1713年发表在他的《猜想论》一书中。

随机游走过程

1905年,卡尔-皮尔逊(Karl Pearson)在提出一个描述平面上随机行走的问题时,创造了随机游走这个术语,其动机是在生物学中的应用,但这种涉及随机行走的问题在其他领域已经得到研究。几个世纪前研究的某些赌博问题也可以被视为涉及随机漫步的问题。[91][285]例如,被称为 "赌徒破产"的问题是基于一个简单的随机行走[39][196],是一个具有吸收障碍的随机行走的例子。[245][83]帕斯卡尔、费马和惠恩斯都给出了这个问题的数值解决方案,但没有详细说明他们的方法[248],然后雅各布-伯努利(Jakob Bernoulli)和亚伯拉罕-德莫伊夫尔( Abraham de Moivre)提出了更详细的解决方案。

对于n维整数格中的随机行走,乔治·波利亚(George Pólya)在1919年和1921年发表了工作,他研究了对称随机行走返回到格子中先前位置的概率。波利亚表明,一个对称的随机行走,在格子的任何方向前进的概率都是相同的,在一维和二维中会以概率1返回到格子中的前一个位置,但在三维或更高维度中概率为零[286][287]。

维纳过程

维纳过程或布朗运动过程起源于不同的领域,包括统计学、金融学和物理学[23]。1880年,托瓦尔·蒂勒(Thorvald Thiele)写了一篇关于最小二乘法的论文,他用这个过程来研究时间序列分析中模型的误差。[288][289][290]这项工作现在被认为是卡尔曼滤波的统计方法的早期发现,但这项工作在很大程度上被忽略了。人们认为蒂勒的论文中的观点太过先进,以至于当时更广泛的数学和统计学界都不理解。[290]

法国数学家路易斯·巴施里耶 (Louis Bachelier)在他1900年的论文中使用了维纳过程[291][292]以模拟巴黎证券交易所的价格变化,[293]但他并不知道蒂勒的工作。[23]有人猜测巴施里耶从朱尔斯·雷格诺尔(Jules Regnault)的随机漫步模型中汲取了灵感,但Bachelier并没有引用他的话[294],而巴施里耶的论文现在被认为是金融数学领域的先驱。

人们普遍认为,巴施里耶的作品没有获得什么关注,被遗忘了几十年,直到20世纪50年代被伦纳德-萨维奇重新发现,然后在1964年被翻译成英文后变得更加流行。但这项工作在数学界从未被遗忘,因为巴施里耶在1912年出版了一本书,详细介绍了他的想法,[294]这本书被包括杜布、费勒[294]和科尔莫戈罗夫[23]在内的数学家所引用。这本书仍然被引用着,但后来从1960年代开始,当经济学家开始引用巴施里耶的工作时,巴施里耶的原始论文开始被引用得多于他的书[294]。

1905年,阿尔伯特-爱因斯坦发表了一篇论文,他研究了布朗运动或运动的物理观察,通过使用气体动力学理论的思想来解释液体中颗粒的看似随机的运动。爱因斯坦推导出一个被称为扩散方程的微分方程,用于描述在某一空间区域找到一个粒子的概率。在爱因斯坦发表第一篇关于布朗运动的论文后不久,马里安-斯莫鲁奇夫斯基( Marian Smoluchowski)发表了他引用爱因斯坦的作品,但他写道,他通过使用不同的方法独立得出了同等的结果[295]。

爱因斯坦的工作,以及让-佩兰获得的实验结果,后来在20世纪20年代启发了诺伯特-维纳[296],他使用珀西-丹尼尔发展的一种度量理论和傅里叶分析来证明维纳过程作为一个数学对象的存在[23]。

泊松过程

泊松过程是以西梅翁·泊松(Siméon Poisson)的名字命名的,因为其定义涉及泊松分布,但泊松从未研究过这个过程[24][297]。有许多关于泊松过程的早期使用或发现的说法[24][26]。在20世纪初,泊松过程会在不同的情况下独立出现[24][26]。1903年在瑞典,菲利普-伦德伯格( Filip Lundberg)发表了一篇论文,其中包含的工作现在被认为是基本的和开创性的,他提出用一个齐次泊松过程来模拟保险索赔[298][299]。

另一项发现发生在1909年的丹麦,当时尔朗(A.K.Erlang)在为有限时间间隔内的来电数量开发一个数学模型时得出了泊松分布。尔朗当时并不知道泊松的早期工作,他假设每个时间间隔内到达的电话数量是相互独立的。然后,他发现了极限情况,这实际上是将泊松分布重塑为二项分布的极限[24]。

1910年,欧内斯特-卢瑟福(Ernest Rutherford )和汉斯-盖格(Hans Geiger )发表了关于α粒子计数的实验结果。在他们工作的推动下,哈里-贝特曼(Harry Bateman)研究了计数问题,并推导出泊松概率作为一组微分方程的解,从而独立发现了泊松过程。[24] 在这之后,有许多关于泊松过程的研究和应用,但其早期历史很复杂,生物学家、生态学家、工程师和各种物理科学家在众多领域对该过程的各种应用已经说明了这一点[24]。

马尔可夫过程

马尔可夫过程和马尔可夫链是以安德烈-马尔可夫命名的,他在20世纪初研究了马尔可夫链[300]。马尔可夫对研究独立随机序列的扩展很感兴趣[300]。在他于1906年发表的第一篇关于马尔可夫链的论文中,马尔可夫表明,在某些条件下,马尔可夫链的平均结果会收敛到一个固定的数值向量,因此证明了一个没有独立假设的弱大数法则,[301][302] [303][304] ,而独立假设曾被普遍认为是这种数学定律成立的条件之一[304]。 马尔可夫后来用马尔可夫链来研究亚历山大-普希金写的《欧仁-奥涅金》中元音的分布,并证明了这种链的中心极限定理[301][302]。

1912年,庞加莱(Poincaré)研究了有限群上的马尔科夫链,目的是研究重排。马尔科夫链的其他早期应用包括保罗(Paul)和塔季扬娜-埃伦费斯特(Tatyana Ehrenfest)在1907年提出的扩散模型,以及弗朗西斯-高尔顿(Francis Galton)和亨利-威廉-沃森(Henry William Watson)在1873年提出的分支过程,比马尔科夫的工作更早。[302] [303]在高尔顿和沃森的工作之后,人们发现他们的分支过程在大约三十年前就被伊雷内-朱尔·比内梅(Irénée-Jules Bienaymé)独立发现和研究了[305]。从1928年开始,莫里斯·弗雷歇(Maurice Fréchet)开始对马尔科夫链感兴趣,最终导致他在1938年发表了一篇关于马尔科夫链的详细研究[302][306]。

安德雷·柯尔莫哥洛夫(Andrei Kolmogorov)在1931年的一篇论文中发展了早期连续时间马尔可夫过程的大部分理论[255][261]。柯尔莫哥洛夫部分受到了路易斯·巴施里耶(Louis Bachelier)1900年关于股票市场波动的工作以及诺伯特·维纳(Norbert Wiener)关于爱因斯坦布朗运动模型的工作的启发。[261][307] 他引入并研究了一组被称为扩散过程的特殊马尔可夫过程,然后在其上推导了一组描述该过程的微分方程[261][308]。独立于柯尔莫哥洛夫的工作,悉尼-查普曼(Sydney Chapman)在1928年的一篇论文中,以比柯尔莫哥洛夫更不严格的数学方式,在研究布朗运动时得出了一个方程[309],现在称为查普曼-科尔莫戈罗夫方程。这些微分方程现在被称为科尔莫戈罗夫方程[310]或科尔莫戈罗夫-查普曼方程[311]。对马尔科夫过程的基础作出重大贡献的其他数学家包括从1930年代开始的威廉-费勒(William Feller),后来又有从1950年代开始的尤金-代金(Eugene Dynkin)。

莱维过程

像维纳过程和泊松过程一样的莱维过程由1930年带学习他们的保罗·莱维(Paul Lévy)命名[227],但是它们与无限可分分布的联系可以追溯到20世纪20年代[226]。这一结果后来由莱维于1934年在更一般的条件下推导出来,然后辛钦(Khinchin)在1937年独立地给出了这一特征函数的另一种形式[255][312]。除了莱维、辛钦和柯尔莫哥洛夫之外,福内梯B(runo de Finetti)和伊藤清(Kiyosi Itô)也对莱维过程的理论做出了早期的基本贡献[226]。

参考文献

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Joseph L. Doob (1990). Stochastic processes. Wiley. pp. 46, 47. https://books.google.com/books?id=7Bu8jgEACAAJ.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 L. C. G. Rogers; David Williams (2000). Diffusions, Markov Processes, and Martingales: Volume 1, Foundations. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-107-71749-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=W0ydAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 J. Michael Steele (2012). Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4684-9305-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fsgkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Emanuel Parzen (2015). Stochastic Processes. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 7, 8. ISBN 978-0-486-79688-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=0mB2CQAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Iosif Ilyich Gikhman; Anatoly Vladimirovich Skorokhod (1969). Introduction to the Theory of Random Processes. Courier Corporation. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-486-69387-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=q0lo91imeD0C.

- ↑ Gagniuc, Paul A. (2017). Markov Chains: From Theory to Implementation and Experimentation. NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–235. ISBN 978-1-119-38755-8.

- ↑ Paul C. Bressloff (2014). Stochastic Processes in Cell Biology. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-08488-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=SwZYBAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ N.G. Van Kampen (2011). Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-047536-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=N6II-6HlPxEC.

- ↑ Russell Lande; Steinar Engen; Bernt-Erik Sæther (2003). Stochastic Population Dynamics in Ecology and Conservation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852525-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=6KClauq8OekC.

- ↑ Carlo Laing; Gabriel J Lord (2010). Stochastic Methods in Neuroscience. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-923507-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=RaYSDAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Wolfgang Paul; Jörg Baschnagel (2013). Stochastic Processes: From Physics to Finance. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-319-00327-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=OWANAAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Edward R. Dougherty (1999). Random processes for image and signal processing. SPIE Optical Engineering Press. ISBN 978-0-8194-2513-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=ePxDAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Dimitri P. Bertsekas (1996). Stochastic Optimal Control: The Discrete-Time Case. Athena Scientific]. ISBN 1-886529-03-5. http://www.athenasc.com/socbook.html.

- ↑ Thomas M. Cover; Joy A. Thomas (2012). Elements of Information Theory. John Wiley & Sons. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-118-58577-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=VWq5GG6ycxMC=PT16.

- ↑ Michael Baron (2015). Probability and Statistics for Computer Scientists, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-4987-6060-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=CwQZCwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Jonathan Katz; Yehuda Lindell (2007). Introduction to Modern Cryptography: Principles and Protocols. CRC Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-58488-586-3. https://archive.org/details/Introduction_to_Modern_Cryptography.

- ↑ François Baccelli; Bartlomiej Blaszczyszyn (2009). Stochastic Geometry and Wireless Networks. Now Publishers Inc. ISBN 978-1-60198-264-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=H3ZkTN2pYS4C.

- ↑ J. Michael Steele (2001). Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-95016-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=H06xzeRQgV4C.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Marek Musiela; Marek Rutkowski (2006). Martingale Methods in Financial Modelling. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-26653-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=iojEts9YAxIC.

- ↑ Steven E. Shreve (2004). Stochastic Calculus for Finance II: Continuous-Time Models. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-40101-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=O8kD1NwQBsQC.

- ↑ Iosif Ilyich Gikhman; Anatoly Vladimirovich Skorokhod (1969). Introduction to the Theory of Random Processes. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-69387-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=yJyLzG7N7r8C.

- ↑ Murray Rosenblatt (1962). Random Processes. Oxford University Press. https://archive.org/details/randomprocesses00rose_0.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 Jarrow, Robert; Protter, Philip (2004). "A short history of stochastic integration and mathematical finance: the early years, 1880–1970". A Festschrift for Herman Rubin. Institute of Mathematical Statistics Lecture Notes - Monograph Series. pp. 75–80. doi:10.1214/lnms/1196285381. ISBN 978-0-940600-61-4. ISSN 0749-2170.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 Stirzaker, David (2000). "Advice to Hedgehogs, or, Constants Can Vary". The Mathematical Gazette. 84 (500): 197–210. doi:10.2307/3621649. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 3621649.

- ↑ Donald L. Snyder; Michael I. Miller (2012). Random Point Processes in Time and Space. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4612-3166-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=c_3UBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Guttorp, Peter; Thorarinsdottir, Thordis L. (2012). "What Happened to Discrete Chaos, the Quenouille Process, and the Sharp Markov Property? Some History of Stochastic Point Processes". International Statistical Review. 80 (2): 253–268. doi:10.1111/j.1751-5823.2012.00181.x. ISSN 0306-7734.

- ↑ Gusak, Dmytro; Kukush, Alexander; Kulik, Alexey; Mishura, Yuliya; Pilipenko, Andrey (2010). Theory of Stochastic Processes: With Applications to Financial Mathematics and Risk Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-387-87862-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=8Nzn51YTbX4C.

- ↑ Valeriy Skorokhod (2005). Basic Principles and Applications of Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 42. ISBN 978-3-540-26312-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=dQkYMjRK3fYC.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Olav Kallenberg (2002). Foundations of Modern Probability. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-387-95313-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=L6fhXh13OyMC.

- ↑ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 30.10 30.11 30.12 30.13 30.14 John Lamperti (1977). Stochastic processes: a survey of the mathematical theory. Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-3-540-90275-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pd4cvgAACAAJ.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Loïc Chaumont; Marc Yor (2012). Exercises in Probability: A Guided Tour from Measure Theory to Random Processes, Via Conditioning. Cambridge University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-107-60655-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=1dcqV9mtQloC&pg=PR4.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 Robert J. Adler; Jonathan E. Taylor (2009). Random Fields and Geometry. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-387-48116-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=R5BGvQ3ejloC.

- ↑ Gregory F. Lawler; Vlada Limic (2010). Random Walk: A Modern Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48876-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=UBQdwAZDeOEC.

- ↑ David Williams (1991). Probability with Martingales. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40605-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=e9saZ0YSi-AC.

- ↑ L. C. G. Rogers; David Williams (2000). Diffusions, Markov Processes, and Martingales: Volume 1, Foundations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-71749-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=W0ydAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA1.

- ↑ David Applebaum (2004). Lévy Processes and Stochastic Calculus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83263-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=q7eDUjdJxIkC.

- ↑ Mikhail Lifshits (2012). Lectures on Gaussian Processes. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-24939-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=03m2UxI-UYMC.

- ↑ Robert J. Adler (2010). The Geometry of Random Fields. SIAM. ISBN 978-0-89871-693-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=ryejJmJAj28C&pg=PA1.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ Bruce Hajek (2015). Random Processes for Engineers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-24124-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Owy0BgAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 G. Latouche; V. Ramaswami (1999). Introduction to Matrix Analytic Methods in Stochastic Modeling. SIAM. ISBN 978-0-89871-425-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=Kan2ki8jqzgC.

- ↑ D.J. Daley; David Vere-Jones (2007). An Introduction to the Theory of Point Processes: Volume II: General Theory and Structure. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-21337-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=nPENXKw5kwcC.

- ↑ Applebaum, David (2004). "Lévy processes: From probability to finance and quantum groups". Notices of the AMS. 51 (11): 1336–1347.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Jochen Blath; Peter Imkeller; Sylvie Rœlly (2011). Surveys in Stochastic Processes. European Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-3-03719-072-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=CyK6KAjwdYkC.

- ↑ Michel Talagrand (2014). Upper and Lower Bounds for Stochastic Processes: Modern Methods and Classical Problems. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-3-642-54075-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=tfa5BAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ Paul C. Bressloff (2014). Stochastic Processes in Cell Biology. Springer. pp. vii–ix. ISBN 978-3-319-08488-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=SwZYBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 48.6 48.7 48.8 Applebaum, David (2004). "Lévy processes: From probability to finance and quantum groups". Notices of the AMS. 51 (11): 1337.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 L. C. G. Rogers; David Williams (2000). Diffusions, Markov Processes, and Martingales: Volume 1, Foundations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–124. ISBN 978-1-107-71749-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=W0ydAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA1.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 294, 295. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ Donald L. Snyder; Michael I. Miller (2012). Random Point Processes in Time and Space. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 24, 25. ISBN 978-1-4612-3166-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=c_3UBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Patrick Billingsley (2008). Probability and Measure. Wiley India Pvt. Limited. p. 482. ISBN 978-81-265-1771-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=QyXqOXyxEeIC.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Alexander A. Borovkov (2013). Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 527. ISBN 978-1-4471-5201-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=hRk_AAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Pierre Brémaud (2014). Fourier Analysis and Stochastic Processes. Springer. p. 120. ISBN 978-3-319-09590-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=dP2JBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Jeffrey S Rosenthal (2006). A First Look at Rigorous Probability Theory. World Scientific Publishing Co Inc. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-981-310-165-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=am1IDQAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Peter E. Kloeden; Eckhard Platen (2013). Numerical Solution of Stochastic Differential Equations. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 63. ISBN 978-3-662-12616-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=r9r6CAAAQBAJ=PA1.

- ↑ Davar Khoshnevisan (2006). Multiparameter Processes: An Introduction to Random Fields. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 153–155. ISBN 978-0-387-21631-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=XADpBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 294, 295. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 {Cite OED | random}

- ↑ O. B. Sheĭnin (2006). Theory of probability and statistics as exemplified in short dictums. NG Verlag. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-938417-40-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=XqMZAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Oscar Sheynin; Heinrich Strecker (2011). Alexandr A. Chuprov: Life, Work, Correspondence. V&R unipress GmbH. p. 136. ISBN 978-3-89971-812-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=1EJZqFIGxBIC&pg=PA9.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Doob, Joseph (1934). "Stochastic Processes and Statistics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 20 (6): 376–379. Bibcode:1934PNAS...20..376D. doi:10.1073/pnas.20.6.376. PMC 1076423. PMID 16587907.

- ↑ Khintchine, A. (1934). "Korrelationstheorie der stationeren stochastischen Prozesse". Mathematische Annalen. 109 (1): 604–615. doi:10.1007/BF01449156. ISSN 0025-5831.

- ↑ Kolmogoroff, A. (1931). "Über die analytischen Methoden in der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung". Mathematische Annalen. 104 (1): 1. doi:10.1007/BF01457949. ISSN 0025-5831.

- ↑ {Cite OED | random}

- ↑ Bert E. Fristedt; Lawrence F. Gray (2013). A Modern Approach to Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 580. ISBN 978-1-4899-2837-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=9xT3BwAAQBAJ&pg=PA716.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 L. C. G. Rogers; David Williams (2000). Diffusions, Markov Processes, and Martingales: Volume 1, Foundations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 121, 122. ISBN 978-1-107-71749-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=W0ydAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA1.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Søren Asmussen (2003). Applied Probability and Queues. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-387-00211-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=BeYaTxesKy0C.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 David Stirzaker (2005). Stochastic Processes and Models. Oxford University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-19-856814-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=0avUelS7e7cC.

- ↑ Murray Rosenblatt (1962). Random Processes. Oxford University Press. p. 91. https://archive.org/details/randomprocesses00rose_0.

- ↑ John A. Gubner (2006). Probability and Random Processes for Electrical and Computer Engineers. Cambridge University Press. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-139-45717-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=pa20eZJe4LIC.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Kiyosi Itō (2006). Essentials of Stochastic Processes. American Mathematical Soc.. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8218-3898-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=pY5_DkvI-CcC&pg=PR4.

- ↑ M. Loève (1978). Probability Theory II. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-387-90262-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=1y229yBbULIC.

- ↑ Pierre Brémaud (2014). Fourier Analysis and Stochastic Processes. Springer. p. 133. ISBN 978-3-319-09590-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=dP2JBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 p. 1

- ↑ Richard F. Bass (2011). Stochastic Processes. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-139-50147-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ll0T7PIkcKMC.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 ,John Lamperti (1977). Stochastic processes: a survey of the mathematical theory. Springer-Verlag. p. 3. ISBN 978-3-540-90275-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pd4cvgAACAAJ.

- ↑ Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 293. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Florescu, Ionut (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ Dimitri P. Bertsekas; John N. Tsitsiklis (2002). Introduction to Probability. Athena Scientific. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-886529-40-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=bcHaAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Oliver C. Ibe (2013). Elements of Random Walk and Diffusion Processes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-118-61793-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=DUqaAAAAQBAJ&pg=PT10.

- ↑ Achim Klenke (2013). Probability Theory: A Comprehensive Course. Springer. pp. 347. ISBN 978-1-4471-5362-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=aqURswEACAAJ.

- ↑ Gregory F. Lawler; Vlada Limic (2010). Random Walk: A Modern Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-139-48876-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=UBQdwAZDeOEC.

- ↑ Olav Kallenberg (2002). Foundations of Modern Probability. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-387-95313-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=L6fhXh13OyMC.

- ↑ Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ Rick Durrett (2010). Probability: Theory and Examples. Cambridge University Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-139-49113-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=evbGTPhuvSoC.

- ↑ {cite book | last1=Weiss | first1=George H.| title=Statistical Sciences | chapter=Random Walks | year=2006 | doi=10.1002/0471667196.ess2180.pub2 | page=1 | isbn=978-0471667193}}

- ↑ Aris Spanos (1999). Probability Theory and Statistical Inference: Econometric Modeling with Observational Data. Cambridge University Press. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-521-42408-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=G0_HxBubGAwC.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Weiss, George H. (2006). "Random Walks". Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. p. 1. doi:10.1002/0471667196.ess2180.pub2. ISBN 978-0471667193.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ Allan Gut (2012). Probability: A Graduate Course. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-4614-4708-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=XDFA-n_M5hMC.

- ↑ Geoffrey Grimmett; David Stirzaker (2001). Probability and Random Processes. OUP Oxford. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-19-857222-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=G3ig-0M4wSIC.

- ↑ Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ Brush, Stephen G. (1968). "A history of random processes". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 5 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1007/BF00328110. ISSN 0003-9519.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Applebaum, David (2004). "Lévy processes: From probability to finance and quantum groups". Notices of the AMS. 51 (11): 1338.

- ↑ Iosif Ilyich Gikhman; Anatoly Vladimirovich Skorokhod (1969). Introduction to the Theory of Random Processes. Courier Corporation. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-486-69387-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=yJyLzG7N7r8C&pg=PR2.

- ↑ Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 471. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. pp. 21, 22. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ Ioannis Karatzas; Steven Shreve (1991). Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer. p. VIII. ISBN 978-1-4612-0949-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=w0SgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT5.

- ↑ Daniel Revuz; Marc Yor (2013). Continuous Martingales and Brownian Motion. Springer Science & Business Media. p. IX. ISBN 978-3-662-06400-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=OYbnCAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Jeffrey S Rosenthal (2006). A First Look at Rigorous Probability Theory. World Scientific Publishing Co Inc. p. 186. ISBN 978-981-310-165-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=am1IDQAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Donald L. Snyder; Michael I. Miller (2012). Random Point Processes in Time and Space. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4612-3166-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=c_3UBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ J. Michael Steele (2012). Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-4684-9305-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fsgkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Peter Mörters; Yuval Peres (2010). Brownian Motion. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1, 3. ISBN 978-1-139-48657-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=e-TbA-dSrzYC.

- ↑ Ioannis Karatzas; Steven Shreve (1991). Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4612-0949-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=w0SgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT5.

- ↑ Ioannis Karatzas; Steven Shreve (1991). Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-4612-0949-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=w0SgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT5.

- ↑ Steven E. Shreve (2004). Stochastic Calculus for Finance II: Continuous-Time Models. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-387-40101-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=O8kD1NwQBsQC.

- ↑ Olav Kallenberg (2002). Foundations of Modern Probability. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 225, 260. ISBN 978-0-387-95313-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=L6fhXh13OyMC.

- ↑ Ioannis Karatzas; Steven Shreve (1991). Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4612-0949-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=w0SgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT5.

- ↑ Peter Mörters; Yuval Peres (2010). Brownian Motion. Cambridge University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-139-48657-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=e-TbA-dSrzYC.

- ↑ Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ Ioannis Karatzas; Steven Shreve (1991). Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4612-0949-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=w0SgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT5.

- ↑ Applebaum, David (2004). "Lévy processes: From probability to finance and quantum groups". Notices of the AMS. 51 (11): 1341.

- ↑ Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ Ioannis Karatzas; Steven Shreve (1991). Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4612-0949-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=w0SgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT5.

- ↑ Ubbo F. Wiersema (2008). Brownian Motion Calculus. John Wiley & Sons. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-470-02171-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=0h-n0WWuD9cC.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Henk C. Tijms (2003). A First Course in Stochastic Models. Wiley. pp. 1, 2. ISBN 978-0-471-49881-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=eBeNngEACAAJ.

- ↑ D.J. Daley; D. Vere-Jones (2006). An Introduction to the Theory of Point Processes: Volume I: Elementary Theory and Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 19–36. ISBN 978-0-387-21564-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=6Sv4BwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Henk C. Tijms (2003). A First Course in Stochastic Models. Wiley. pp. 1, 2. ISBN 978-0-471-49881-0.

- ↑ Mark A. Pinsky; Samuel Karlin (2011). An Introduction to Stochastic Modeling. Academic Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-12-381416-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=PqUmjp7k1kEC.

- ↑ J. F. C. Kingman (1992). Poisson Processes. Clarendon Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-19-159124-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VEiM-OtwDHkC.

- ↑ D.J. Daley; D. Vere-Jones (2006). An Introduction to the Theory of Point Processes: Volume I: Elementary Theory and Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-387-21564-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=6Sv4BwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ J. F. C. Kingman (1992). Poisson Processes. Clarendon Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-159124-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VEiM-OtwDHkC.

- ↑ Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. pp. 118, 119. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ Leonard Kleinrock (1976). Queueing Systems: Theory. Wiley. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-471-49110-1. https://archive.org/details/queueingsystems00klei.

- ↑ Murray Rosenblatt (1962). Random Processes. Oxford University Press. p. 94. https://archive.org/details/randomprocesses00rose_0.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 Martin Haenggi (2013). Stochastic Geometry for Wireless Networks. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10, 18. ISBN 978-1-107-01469-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=CLtDhblwWEgC.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 Sung Nok Chiu; Dietrich Stoyan; Wilfrid S. Kendall; Joseph Mecke (2013). Stochastic Geometry and Its Applications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 41, 108. ISBN 978-1-118-65825-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=825NfM6Nc-EC.

- ↑ J. F. C. Kingman (1992). Poisson Processes. Clarendon Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-159124-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VEiM-OtwDHkC.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 Roy L. Streit (2010). Poisson Point Processes: Imaging, Tracking, and Sensing. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4419-6923-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=KAWmFYUJ5zsC&pg=PA11.

- ↑ J. F. C. Kingman (1992). Poisson Processes. Clarendon Press. p. v. ISBN 978-0-19-159124-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VEiM-OtwDHkC.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 Alexander A. Borovkov (2013). Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 528. ISBN 978-1-4471-5201-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=hRk_AAAAQBAJ&pg.

- ↑ Georg Lindgren; Holger Rootzen; Maria Sandsten (2013). Stationary Stochastic Processes for Scientists and Engineers. CRC Press. pp. 11. ISBN 978-1-4665-8618-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=FYJFAQAAQBAJ&pg=PR1.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 137.2 Valeriy Skorokhod (2005). Basic Principles and Applications of Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 93, 94. ISBN 978-3-540-26312-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=dQkYMjRK3fYC.

- ↑ Donald L. Snyder; Michael I. Miller (2012). Random Point Processes in Time and Space. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4612-3166-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=c_3UBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Valeriy Skorokhod (2005). Basic Principles and Applications of Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 104. ISBN 978-3-540-26312-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=dQkYMjRK3fYC.

- ↑ Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ Patrick Billingsley (2008). Probability and Measure. Wiley India Pvt. Limited. p. 493. ISBN 978-81-265-1771-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=QyXqOXyxEeIC.

- ↑ Bernt Øksendal (2003). Stochastic Differential Equations: An Introduction with Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-540-04758-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VgQDWyihxKYC.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 143.2 143.3 143.4 Peter K. Friz; Nicolas B. Victoir (2010). Multidimensional Stochastic Processes as Rough Paths: Theory and Applications. Cambridge University Press. p. 571. ISBN 978-1-139-48721-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=CVgwLatxfGsC.

- ↑ Sidney I. Resnick (2013). Adventures in Stochastic Processes. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1-4612-0387-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VQrpBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ John Lamperti (1977). Stochastic processes: a survey of the mathematical theory. Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-3-540-90275-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pd4cvgAACAAJ.

- ↑ Ward Whitt (2006). Stochastic-Process Limits: An Introduction to Stochastic-Process Limits and Their Application to Queues. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-387-21748-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=LkQOBwAAQBAJ&pg=PR5.

- ↑ David Applebaum (2004). Lévy Processes and Stochastic Calculus. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-83263-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=q7eDUjdJxIkC.

- ↑ Daniel Revuz; Marc Yor (2013). Continuous Martingales and Brownian Motion. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-662-06400-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=OYbnCAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ L. C. G. Rogers; David Williams (2000). Diffusions, Markov Processes, and Martingales: Volume 1, Foundations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123. ISBN 978-1-107-71749-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=W0ydAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA356.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 150.2 150.3 John Lamperti (1977). Stochastic processes: a survey of the mathematical theory. Springer-Verlag. pp. 6 and 7. ISBN 978-3-540-90275-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pd4cvgAACAAJ.

- ↑ Iosif I. Gikhman; Anatoly Vladimirovich Skorokhod (1969). Introduction to the Theory of Random Processes. Courier Corporation. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-486-69387-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=yJyLzG7N7r8C&pg=PR2.

- ↑ 152.0 152.1 152.2 152.3 Robert J. Adler (2010). The Geometry of Random Fields. SIAM. pp. 14, 15. ISBN 978-0-89871-693-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=ryejJmJAj28C&pg=PA263.

- ↑ Sung Nok Chiu; Dietrich Stoyan; Wilfrid S. Kendall; Joseph Mecke (2013). Stochastic Geometry and Its Applications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-118-65825-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=825NfM6Nc-EC.

- ↑ 154.0 154.1 Joseph L. Doob (1990). Stochastic processes. Wiley. pp. 94–96. https://books.google.com/books?id=NrsrAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ 155.0 155.1 Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 298, 299. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ Iosif Ilyich Gikhman; Anatoly Vladimirovich Skorokhod (1969). Introduction to the Theory of Random Processes. Courier Corporation. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-486-69387-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=yJyLzG7N7r8C&pg=PR2.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 157.2 David Williams (1991). Probability with Martingales. Cambridge University Press. pp. 93, 94. ISBN 978-0-521-40605-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=e9saZ0YSi-AC.

- ↑ Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ Peter Mörters; Yuval Peres (2010). Brownian Motion. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-139-48657-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=e-TbA-dSrzYC.

- ↑ 160.0 160.1 L. C. G. Rogers; David Williams (2000). Diffusions, Markov Processes, and Martingales: Volume 1, Foundations. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-107-71749-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=W0ydAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA356.

- ↑ Alexander A. Borovkov (2013). Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 530. ISBN 978-1-4471-5201-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=hRk_AAAAQBAJ&pg.

- ↑ Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ 163.0 163.1 Bernt Øksendal (2003). Stochastic Differential Equations: An Introduction with Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 14. ISBN 978-3-540-04758-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VgQDWyihxKYC.

- ↑ 164.0 164.1 Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 472. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ Daniel Revuz; Marc Yor (2013). Continuous Martingales and Brownian Motion. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-3-662-06400-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=OYbnCAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ David Applebaum (2004). Lévy Processes and Stochastic Calculus. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-83263-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=q7eDUjdJxIkC.

- ↑ Hiroshi Kunita (1997). Stochastic Flows and Stochastic Differential Equations. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-59925-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=_S1RiCosqbMC.

- ↑ Olav Kallenberg (2002). Foundations of Modern Probability. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-387-95313-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=L6fhXh13OyMC.

- ↑ Monique Jeanblanc; Marc Yor; Marc Chesney (2009). Mathematical Methods for Financial Markets. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-85233-376-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZhbROxoQ-ZMC.

- ↑ 170.0 170.1 170.2 Kiyosi Itō (2006). Essentials of Stochastic Processes. American Mathematical Soc.. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-8218-3898-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=pY5_DkvI-CcC&pg=PR4.

- ↑ Iosif Ilyich Gikhman; Anatoly Vladimirovich Skorokhod (1969). Introduction to the Theory of Random Processes. Courier Corporation. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-486-69387-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=yJyLzG7N7r8C&pg=PR2.

- ↑ 172.0 172.1 Petar Todorovic (2012). An Introduction to Stochastic Processes and Their Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-1-4613-9742-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=XpjqBwAAQBAJ&pg=PP5.

- ↑ Ilya Molchanov (2005). Theory of Random Sets. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-85233-892-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=kWEwk1UL42AC.

- ↑ 174.0 174.1 Patrick Billingsley (2008). Probability and Measure. Wiley India Pvt. Limited. pp. 526–527. ISBN 978-81-265-1771-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=QyXqOXyxEeIC.

- ↑ Alexander A. Borovkov (2013). Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 535. ISBN 978-1-4471-5201-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=hRk_AAAAQBAJ&pg.

- ↑ Gusak, Dmytro; Kukush, Alexander; Kulik, Alexey; Mishura, Yuliya; Pilipenko, Andrey (2010). Theory of Stochastic Processes: With Applications to Financial Mathematics and Risk Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-387-87862-1.

- ↑ Joseph L. Doob (1990). Stochastic processes. Wiley. pp. 56. https://books.google.com/books?id=NrsrAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ Davar Khoshnevisan (2006). Multiparameter Processes: An Introduction to Random Fields. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-387-21631-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=XADpBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Lapidoth, Amos, A Foundation in Digital Communication, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- ↑ 180.0 180.1 Kun Il Park, Fundamentals of Probability and Stochastic Processes with Applications to Communications, Springer, 2018, 978-3-319-68074-3

- ↑ 181.0 181.1 181.2 181.3 Ward Whitt (2006). Stochastic-Process Limits: An Introduction to Stochastic-Process Limits and Their Application to Queues. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-387-21748-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=LkQOBwAAQBAJ&pg=PR5.

- ↑ 182.0 182.1 Gusak, Dmytro; Kukush, Alexander; Kulik, Alexey; Mishura, Yuliya; Pilipenko, Andrey (2010). Theory of Stochastic Processes: With Applications to Financial Mathematics and Risk Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-387-87862-1., p. 24

- ↑ 183.0 183.1 183.2 183.3 Vladimir I. Bogachev (2007). Measure Theory (Volume 2). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-540-34514-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=CoSIe7h5mTsC.

- ↑ 184.0 184.1 184.2 Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ 185.0 185.1 Søren Asmussen (2003). Applied Probability and Queues. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-387-00211-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=BeYaTxesKy0C.

- ↑ 186.0 186.1 186.2 Patrick Billingsley (2013). Convergence of Probability Measures. John Wiley & Sons. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-118-62596-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=6ItqtwaWZZQC.

- ↑ Richard F. Bass (2011). Stochastic Processes. Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-139-50147-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ll0T7PIkcKMC.

- ↑ Nicholas H. Bingham; Rüdiger Kiesel (2013). Risk-Neutral Valuation: Pricing and Hedging of Financial Derivatives. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4471-3856-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=AOIlBQAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Alexander A. Borovkov (2013). Probability Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 532. ISBN 978-1-4471-5201-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=hRk_AAAAQBAJ&pg.

- ↑ Davar Khoshnevisan (2006). Multiparameter Processes: An Introduction to Random Fields. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 148–165. ISBN 978-0-387-21631-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=XADpBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Petar Todorovic (2012). An Introduction to Stochastic Processes and Their Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4613-9742-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=XpjqBwAAQBAJ&pg=PP5.

- ↑ Ward Whitt (2006). Stochastic-Process Limits: An Introduction to Stochastic-Process Limits and Their Application to Queues. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-387-21748-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=LkQOBwAAQBAJ&pg=PR5.

- ↑ Richard Serfozo (2009). Basics of Applied Stochastic Processes. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-540-89332-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=JBBRiuxTN0QC.

- ↑ Y.A. Rozanov (2012). Markov Random Fields. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4613-8190-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=wGUECAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Sheldon M. Ross (1996). Stochastic processes. Wiley. pp. 235, 358. ISBN 978-0-471-12062-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=ImUPAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 196.0 196.1 Ionut Florescu (2014). Probability and Stochastic Processes. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 373, 374. ISBN 978-1-118-59320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z5xEBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR22.

- ↑ Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ 198.0 198.1 Søren Asmussen (2003). Applied Probability and Queues. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-387-00211-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=BeYaTxesKy0C.

- ↑ Emanuel Parzen (2015). Stochastic Processes. Courier Dover Publications. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-486-79688-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=0mB2CQAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. pp. 29, 30. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ John Lamperti (1977). Stochastic processes: a survey of the mathematical theory. Springer-Verlag. pp. 106–121. ISBN 978-3-540-90275-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pd4cvgAACAAJ.

- ↑ Sheldon M. Ross (1996). Stochastic processes. Wiley. pp. 174, 231. ISBN 978-0-471-12062-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=ImUPAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Sean Meyn; Richard L. Tweedie (2009). Markov Chains and Stochastic Stability. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-73182-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Md7RnYEPkJwC.

- ↑ Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ Reuven Y. Rubinstein; Dirk P. Kroese (2011). Simulation and the Monte Carlo Method. John Wiley & Sons. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-118-21052-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=yWcvT80gQK4C.

- ↑ Dani Gamerman; Hedibert F. Lopes (2006). Markov Chain Monte Carlo: Stochastic Simulation for Bayesian Inference, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-58488-587-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=yPvECi_L3bwC.

- ↑ Y.A. Rozanov (2012). Markov Random Fields. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-4613-8190-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=wGUECAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Donald L. Snyder; Michael I. Miller (2012). Random Point Processes in Time and Space. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4612-3166-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=c_3UBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Pierre Bremaud (2013). Markov Chains: Gibbs Fields, Monte Carlo Simulation, and Queues. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-4757-3124-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=jrPVBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 210.0 210.1 210.2 Fima C. Klebaner (2005). Introduction to Stochastic Calculus with Applications. Imperial College Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-86094-555-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=JYzW0uqQxB0C.

- ↑ 211.0 211.1 211.2 Ioannis Karatzas; Steven Shreve (1991). Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4612-0949-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=w0SgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT5.

- ↑ Joseph L. Doob (1990). Stochastic processes. Wiley. pp. 292, 293. https://books.google.com/books?id=NrsrAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ Gilles Pisier (2016). Martingales in Banach Spaces. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-67946-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=n3JNDAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ 214.0 214.1 J. Michael Steele (2012). Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 12, 13. ISBN 978-1-4684-9305-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fsgkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ 215.0 215.1 P. Hall; C. C. Heyde (2014). Martingale Limit Theory and Its Application. Elsevier Science. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4832-6322-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=gqriBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR10.

- ↑ J. Michael Steele (2012). Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-4684-9305-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fsgkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ Sheldon M. Ross (1996). Stochastic processes. Wiley. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-471-12062-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=ImUPAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 218.0 218.1 J. Michael Steele (2012). Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4684-9305-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fsgkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ Olav Kallenberg (2002). Foundations of Modern Probability. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 96. ISBN 978-0-387-95313-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=L6fhXh13OyMC.

- ↑ J. Michael Steele (2012). Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 371. ISBN 978-1-4684-9305-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fsgkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ J. Michael Steele (2012). Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4684-9305-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fsgkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- ↑ Geoffrey Grimmett; David Stirzaker (2001). Probability and Random Processes. OUP Oxford. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-19-857222-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=G3ig-0M4wSIC.

- ↑ Glasserman, Paul; Kou, Steven (2006). "A Conversation with Chris Heyde". Statistical Science. 21 (2): 292, 293. arXiv:math/0609294. Bibcode:2006math......9294G. doi:10.1214/088342306000000088. ISSN 0883-4237.

- ↑ P. Hall; C. C. Heyde (2014). Martingale Limit Theory and Its Application. Elsevier Science. p. x. ISBN 978-1-4832-6322-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=gqriBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR10.

- ↑ Francois Baccelli; Pierre Bremaud (2013). Elements of Queueing Theory: Palm Martingale Calculus and Stochastic Recurrences. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-662-11657-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=DH3pCAAAQBAJ&pg=PR2.

- ↑ 226.0 226.1 226.2 Jean Bertoin (1998). Lévy Processes. Cambridge University Press. p. viii. ISBN 978-0-521-64632-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=ftcsQgMp5cUC&pg=PR8.

- ↑ 227.0 227.1 227.2 Applebaum, David (2004). "Lévy processes: From probability to finance and quantum groups". Notices of the AMS. 51 (11): 1336.

- ↑ David Applebaum (2004). Lévy Processes and Stochastic Calculus. Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-521-83263-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=q7eDUjdJxIkC.

- ↑ Leonid Koralov; Yakov G. Sinai (2007). Theory of Probability and Random Processes. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 171. ISBN 978-3-540-68829-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=tlWOphOFRgwC.

- ↑ David Applebaum (2004). Lévy Processes and Stochastic Calculus. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-83263-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=q7eDUjdJxIkC.

- ↑ Sung Nok Chiu; Dietrich Stoyan; Wilfrid S. Kendall; Joseph Mecke (2013). Stochastic Geometry and Its Applications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-118-65825-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=825NfM6Nc-EC.

- ↑ Sung Nok Chiu; Dietrich Stoyan; Wilfrid S. Kendall; Joseph Mecke (2013). Stochastic Geometry and Its Applications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-118-65825-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=825NfM6Nc-EC.

- ↑ Martin Haenggi (2013). Stochastic Geometry for Wireless Networks. Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-107-01469-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=CLtDhblwWEgC.

- ↑ D.J. Daley; D. Vere-Jones (2006). An Introduction to the Theory of Point Processes: Volume I: Elementary Theory and Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-387-21564-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=6Sv4BwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 235.0 235.1 D.R. Cox; Valerie Isham (1980). Point Processes. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-412-21910-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=KWF2xY6s3PoC.

- ↑ J. F. C. Kingman (1992). Poisson Processes. Clarendon Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-159124-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VEiM-OtwDHkC.

- ↑ Jesper Moller; Rasmus Plenge Waagepetersen (2003). Statistical Inference and Simulation for Spatial Point Processes. CRC Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-203-49693-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=dBNOHvElXZ4C.

- ↑ Samuel Karlin; Howard E. Taylor (2012). A First Course in Stochastic Processes. Academic Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-08-057041-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dSDxjX9nmmMC.

- ↑ Volker Schmidt (2014). Stochastic Geometry, Spatial Statistics and Random Fields: Models and Algorithms. Springer. p. 99. ISBN 978-3-319-10064-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=brsUBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR5.

- ↑ D.J. Daley; D. Vere-Jones (2006). An Introduction to the Theory of Point Processes: Volume I: Elementary Theory and Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-21564-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=6Sv4BwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ D.R. Cox; Valerie Isham (1980). Point Processes. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-412-21910-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=KWF2xY6s3PoC.

- ↑ 242.0 242.1 242.2 242.3 242.4 242.5 Gagniuc, Paul A. (2017). Markov Chains: From Theory to Implementation and Experimentation. US: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-119-38755-8.

- ↑ David, F. N. (1955). "Studies in the History of Probability and Statistics I. Dicing and Gaming (A Note on the History of Probability)". Biometrika. 42 (1/2): 1–15. doi:10.2307/2333419. ISSN 0006-3444. JSTOR 2333419.

- ↑ L. E. Maistrov (2014). Probability Theory: A Historical Sketch. Elsevier Science. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4832-1863-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=2ZbiBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR9.

- ↑ 245.0 245.1 Seneta, E. (2006). "Probability, History of". Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. p. 1. doi:10.1002/0471667196.ess2065.pub2. ISBN 978-0471667193.

- ↑ John Tabak (2014). Probability and Statistics: The Science of Uncertainty. Infobase Publishing. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-0-8160-6873-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=h3WVqBPHboAC.

- ↑ Bellhouse, David (2005). "Decoding Cardano's Liber de Ludo Aleae". Historia Mathematica. 32 (2): 180–202. doi:10.1016/j.hm.2004.04.001. ISSN 0315-0860.

- ↑ 248.0 248.1 248.2 Anders Hald (2005). A History of Probability and Statistics and Their Applications before 1750. John Wiley & Sons. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-471-72517-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=pOQy6-qnVx8C.

- ↑ L. E. Maistrov (2014). Probability Theory: A Historical Sketch. Elsevier Science. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4832-1863-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=2ZbiBQAAQBAJ&pg=PR9.

- ↑ John Tabak (2014). Probability and Statistics: The Science of Uncertainty. Infobase Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8160-6873-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=h3WVqBPHboAC.

- ↑ 251.0 251.1 Chung, Kai Lai (1998). "Probability and Doob". The American Mathematical Monthly. 105 (1): 28–35. doi:10.2307/2589523. ISSN 0002-9890. JSTOR 2589523.

- ↑ 252.0 252.1 252.2 252.3 252.4 Bingham, N. (2000). "Studies in the history of probability and statistics XLVI. Measure into probability: from Lebesgue to Kolmogorov". Biometrika. 87 (1): 145–156. doi:10.1093/biomet/87.1.145. ISSN 0006-3444.

- ↑ 253.0 253.1 Benzi, Margherita; Benzi, Michele; Seneta, Eugene (2007). "Francesco Paolo Cantelli. b. 20 December 1875 d. 21 July 1966". International Statistical Review. 75 (2): 128. doi:10.1111/j.1751-5823.2007.00009.x. ISSN 0306-7734.

- ↑ Doob, Joseph L. (1996). "The Development of Rigor in Mathematical Probability (1900-1950)". The American Mathematical Monthly. 103 (7): 586–595. doi:10.2307/2974673. ISSN 0002-9890. JSTOR 2974673.

- ↑ 255.0 255.1 255.2 255.3 255.4 255.5 255.6 255.7 255.8 Cramer, Harald (1976). "Half a Century with Probability Theory: Some Personal Recollections". The Annals of Probability. 4 (4): 509–546. doi:10.1214/aop/1176996025. ISSN 0091-1798.

- ↑ Truesdell, C. (1975). "Early kinetic theories of gases". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 15 (1): 22–23. doi:10.1007/BF00327232. ISSN 0003-9519.

- ↑ Brush, Stephen G. (1967). "Foundations of statistical mechanics 1845?1915". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 4 (3): 150–151. doi:10.1007/BF00412958. ISSN 0003-9519.

- ↑ Truesdell, C. (1975). "Early kinetic theories of gases". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 15 (1): 31–32. doi:10.1007/BF00327232. ISSN 0003-9519.

- ↑ Brush, S.G. (1958). "The development of the kinetic theory of gases IV. Maxwell". Annals of Science. 14 (4): 243–255. doi:10.1080/00033795800200147. ISSN 0003-3790.

- ↑ Brush, Stephen G. (1968). "A history of random processes". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 5 (1): 15–16. doi:10.1007/BF00328110. ISSN 0003-9519.

- ↑ 261.0 261.1 261.2 261.3 Kendall, D. G.; Batchelor, G. K.; Bingham, N. H.; Hayman, W. K.; Hyland, J. M. E.; Lorentz, G. G.; Moffatt, H. K.; Parry, W.; Razborov, A. A.; Robinson, C. A.; Whittle, P. (1990). "Andrei Nikolaevich Kolmogorov (1903–1987)". Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society. 22 (1): 33. doi:10.1112/blms/22.1.31. ISSN 0024-6093.

- ↑ Vere-Jones, David (2006). "Khinchin, Aleksandr Yakovlevich". Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. p. 1. doi:10.1002/0471667196.ess6027.pub2. ISBN 978-0471667193.

- ↑ Vere-Jones, David (2006). "Khinchin, Aleksandr Yakovlevich". Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. p. 4. doi:10.1002/0471667196.ess6027.pub2. ISBN 978-0471667193.

- ↑ 264.0 264.1 Snell, J. Laurie (2005). "Obituary: Joseph Leonard Doob". Journal of Applied Probability. 42 (1): 251. doi:10.1239/jap/1110381384. ISSN 0021-9002.

- ↑ Lindvall, Torgny (1991). "W. Doeblin, 1915-1940". The Annals of Probability. 19 (3): 929–934. doi:10.1214/aop/1176990329. ISSN 0091-1798.

- ↑ Getoor, Ronald (2009). "J. L. Doob: Foundations of stochastic processes and probabilistic potential theory". The Annals of Probability. 37 (5): 1655. arXiv:0909.4213. Bibcode:2009arXiv0909.4213G. doi:10.1214/09-AOP465. ISSN 0091-1798. S2CID 17288507.

- ↑ 267.0 267.1 Bingham, N. H. (2005). "Doob: a half-century on". Journal of Applied Probability. 42 (1): 257–266. doi:10.1239/jap/1110381385. ISSN 0021-9002.