工作记忆

此词条暂由彩云小译翻译,未经人工整理和审校,带来阅读不便,请见谅。

Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily.[1] Working memory is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior.[2][3] Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information.[2][4] Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. Working memory is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information. Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

工作记忆是一种能暂时容纳信息的有限容量的认知系统。工作记忆对于推理、决策和行为的指导具有重要作用。工作记忆经常被用作短期记忆的同义词,但是一些理论家认为这两种记忆是不同的,假设工作记忆允许对存储的信息进行操作,而短期记忆仅指短期存储的信息。工作记忆是认知心理学、神经心理学和神经科学的核心理论概念。

History

The term "working memory" was coined by Miller, Galanter, and Pribram,[5][6] and was used in the 1960s in the context of theories that likened the mind to a computer. In 1968, Atkinson and Shiffrin[7] used the term to describe their "short-term store". What we now call working memory was formerly referred to variously as a "short-term store" or short-term memory, primary memory, immediate memory, operant memory, and provisional memory.[8] Short-term memory is the ability to remember information over a brief period (in the order of seconds). Most theorists today use the concept of working memory to replace or include the older concept of short-term memory, marking a stronger emphasis on the notion of manipulating information rather than mere maintenance.

The term "working memory" was coined by Miller, Galanter, and Pribram, and was used in the 1960s in the context of theories that likened the mind to a computer. In 1968, Atkinson and Shiffrin used the term to describe their "short-term store". What we now call working memory was formerly referred to variously as a "short-term store" or short-term memory, primary memory, immediate memory, operant memory, and provisional memory. Short-term memory is the ability to remember information over a brief period (in the order of seconds). Most theorists today use the concept of working memory to replace or include the older concept of short-term memory, marking a stronger emphasis on the notion of manipulating information rather than mere maintenance.

“工作记忆”这个术语是由 Miller,Galanter 和 Pribram 提出的,并在20世纪60年代被用于把大脑比作计算机的理论中。1968年,阿特金森和谢夫林用这个词来形容他们的“短期商店”。我们现在所说的工作记忆以前被称为短期记忆或短期记忆,初级记忆,即时记忆,操作记忆和暂时记忆。短时记忆是在短时间内(以秒为单位)记住信息的能力。今天的大多数理论家使用工作记忆的概念来取代或包含早期的短期记忆的概念,标志着更强调操纵信息的概念,而不仅仅是维持。

The earliest mention of experiments on the neural basis of working memory can be traced back to more than 100 years ago, when Hitzig and Ferrier described ablation experiments of the prefrontal cortex (PFC); they concluded that the frontal cortex was important for cognitive rather than sensory processes.[9] In 1935 and 1936, Carlyle Jacobsen and colleagues were the first to show the deleterious effect of prefrontal ablation on delayed response.[9][10]

The earliest mention of experiments on the neural basis of working memory can be traced back to more than 100 years ago, when Hitzig and Ferrier described ablation experiments of the prefrontal cortex (PFC); they concluded that the frontal cortex was important for cognitive rather than sensory processes. In 1935 and 1936, Carlyle Jacobsen and colleagues were the first to show the deleterious effect of prefrontal ablation on delayed response.

关于工作记忆神经基础实验的最早提及可以追溯到100多年前,当时 Hitzig 和 Ferrier 描述了脑前额叶外皮的消融实验(PFC) ; 他们得出结论,额叶皮层对认知过程比感官过程更重要。1935年和1936年,卡莱尔 · 雅各布森和他的同事们首次发现了前额叶切除对延迟反应的有害影响。

Theories

Numerous models have been proposed for how working memory functions, both anatomically and cognitively. Of those, the two that have been most influential are summarized below.

Numerous models have been proposed for how working memory functions, both anatomically and cognitively. Of those, the two that have been most influential are summarized below.

关于工作记忆在解剖学和认知学上的功能,已经有很多模型被提出。其中,最有影响力的两个概括如下。

The multicomponent model

Baddeley and Hitch's model of working memory

和 Hitch 的工作记忆模型

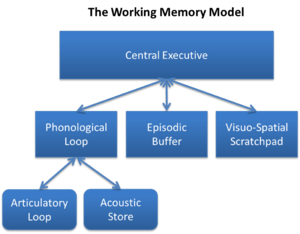

In 1974, Baddeley and Hitch[11] introduced the multicomponent model of working memory. The theory proposed a model containing three components: the central executive, the phonological loop, and the visuospatial sketchpad with the central executive functioning as a control center of sorts, directing info between the phonological and visuospatial components.[12] The central executive is responsible for, among other things, directing attention to relevant information, suppressing irrelevant information and inappropriate actions, and coordinating cognitive processes when more than one task is simultaneously performed. A "central executive" is responsible for supervising the integration of information and for coordinating subordinate systems responsible for the short-term maintenance of information. One subordinate system, the phonological loop (PL), stores phonological information (that is, the sound of language) and prevents its decay by continuously refreshing it in a rehearsal loop. It can, for example, maintain a seven-digit telephone number for as long as one repeats the number to oneself again and again.[13] The other subordinate system, the visuospatial sketchpad, stores visual and spatial information. It can be used, for example, for constructing and manipulating visual images and for representing mental maps. The sketchpad can be further broken down into a visual subsystem (dealing with such phenomena as shape, colour, and texture), and a spatial subsystem (dealing with location).

In 1974, Baddeley and Hitch introduced the multicomponent model of working memory. The theory proposed a model containing three components: the central executive, the phonological loop, and the visuospatial sketchpad with the central executive functioning as a control center of sorts, directing info between the phonological and visuospatial components. The central executive is responsible for, among other things, directing attention to relevant information, suppressing irrelevant information and inappropriate actions, and coordinating cognitive processes when more than one task is simultaneously performed. A "central executive" is responsible for supervising the integration of information and for coordinating subordinate systems responsible for the short-term maintenance of information. One subordinate system, the phonological loop (PL), stores phonological information (that is, the sound of language) and prevents its decay by continuously refreshing it in a rehearsal loop. It can, for example, maintain a seven-digit telephone number for as long as one repeats the number to oneself again and again. The other subordinate system, the visuospatial sketchpad, stores visual and spatial information. It can be used, for example, for constructing and manipulating visual images and for representing mental maps. The sketchpad can be further broken down into a visual subsystem (dealing with such phenomena as shape, colour, and texture), and a spatial subsystem (dealing with location).

1974年,Baddeley 和 Hitch 提出了工作记忆的多元模型。该理论提出了一个包含三个成分的模型: 中央执行器、语音环路和视空间模板,中央执行器作为各种类型的控制中心,在语音和视空间成分之间传递信息。除其他外,中央执行者还负责将注意力引向相关信息,抑制无关信息和不适当的行为,以及在同时执行多个任务时协调认知过程。”中央执行官”负责监督信息的整合,并协调负责短期维护信息的下属系统。一个从属系统,即语音回路(PL) ,存储语音信息(即语音) ,并通过不断刷新它在排练回路中防止其衰退。例如,它可以保持一个七位数的电话号码,只要你一遍又一遍地重复这个号码。另一个辅助系统,视空间画板,存储视觉和空间信息。例如,它可以用于构建和操纵视觉图像,以及用于表示心理地图。画板可以进一步分解为一个视觉子系统(处理形状、颜色和纹理等现象)和一个空间子系统(处理位置)。

In 2000, Baddeley extended the model by adding a fourth component, the episodic buffer, which holds representations that integrate phonological, visual, and spatial information, and possibly information not covered by the subordinate systems (e.g., semantic information, musical information). The episodic buffer is also the link between working memory and long-term memory.[14] The component is episodic because it is assumed to bind information into a unitary episodic representation. The episodic buffer resembles Tulving's concept of episodic memory, but it differs in that the episodic buffer is a temporary store.[15]

In 2000, Baddeley extended the model by adding a fourth component, the episodic buffer, which holds representations that integrate phonological, visual, and spatial information, and possibly information not covered by the subordinate systems (e.g., semantic information, musical information). The episodic buffer is also the link between working memory and long-term memory. The component is episodic because it is assumed to bind information into a unitary episodic representation. The episodic buffer resembles Tulving's concept of episodic memory, but it differs in that the episodic buffer is a temporary store.

2000年,Baddeley 扩展了这个模型,增加了第四个组成部分---- 情景缓冲区,这个缓冲区包含了语音、视觉和空间信息的表征,以及可能不被下属系统覆盖的信息(例如,语义信息、音乐信息)。情景缓冲也是工作记忆和长时记忆之间的纽带。这个成分是情节性的,因为它被假定为将信息绑定成一个单一的情节表示。情景缓冲与图尔文的情景记忆概念相似,但不同之处在于情景缓冲是暂时性的。

Working memory as part of long-term memory

模板:Annotated imageAnders Ericsson and Walter Kintsch[16] have introduced the notion of "long-term working memory", which they define as a set of "retrieval structures" in long-term memory that enable seamless access to the information relevant for everyday tasks. In this way, parts of long-term memory effectively function as working memory. In a similar vein, Cowan does not regard working memory as a separate system from long-term memory. Representations in working memory are a subset of representations in long-term memory. Working memory is organized into two embedded levels. The first consists of long-term memory representations that are activated. There can be many of these—there is theoretically no limit to the activation of representations in long-term memory. The second level is called the focus of attention. The focus is regarded as having a limited capacity and holds up to four of the activated representations.[17]

}}Anders Ericsson and Walter Kintsch have introduced the notion of "long-term working memory", which they define as a set of "retrieval structures" in long-term memory that enable seamless access to the information relevant for everyday tasks. In this way, parts of long-term memory effectively function as working memory. In a similar vein, Cowan does not regard working memory as a separate system from long-term memory. Representations in working memory are a subset of representations in long-term memory. Working memory is organized into two embedded levels. The first consists of long-term memory representations that are activated. There can be many of these—there is theoretically no limit to the activation of representations in long-term memory. The second level is called the focus of attention. The focus is regarded as having a limited capacity and holds up to four of the activated representations.

安德斯 · 埃里克森和沃尔特 · 金奇引入了”长期工作记忆”的概念,他们将其定义为长期记忆中的一组”检索结构” ,使人们能够无缝地获取与日常工作相关的信息。通过这种方式,部分长期记忆有效地起到了工作记忆的作用。同样,考恩并不认为工作记忆是与长期记忆分离的一个系统。工作记忆中的表征是长时记忆中表征的一个子集。工作记忆被组织成两个嵌入的层次。第一种包括被激活的长期记忆表征。其中可能有很多ーー在长时记忆中,理论上对表征的激活是没有限制的。第二个层次叫做注意力焦点。焦点被认为是有一个有限的能力,并持有多达四个激活的表征。

Oberauer has extended Cowan's model by adding a third component, a more narrow focus of attention that holds only one chunk at a time. The one-element focus is embedded in the four-element focus and serves to select a single chunk for processing. For example, four digits can be held in mind at the same time in Cowan's "focus of attention". When the individual wishes to perform a process on each of these digits—for example, adding the number two to each digit—separate processing is required for each digit since most individuals cannot perform several mathematical processes in parallel.[18] Oberauer's attentional component selects one of the digits for processing and then shifts the attentional focus to the next digit, continuing until all digits have been processed.[19]

Oberauer has extended Cowan's model by adding a third component, a more narrow focus of attention that holds only one chunk at a time. The one-element focus is embedded in the four-element focus and serves to select a single chunk for processing. For example, four digits can be held in mind at the same time in Cowan's "focus of attention". When the individual wishes to perform a process on each of these digits—for example, adding the number two to each digit—separate processing is required for each digit since most individuals cannot perform several mathematical processes in parallel. Oberauer's attentional component selects one of the digits for processing and then shifts the attentional focus to the next digit, continuing until all digits have been processed.

通过添加第三个组件扩展了 Cowan 的模型,第三个组件是一个更窄的注意焦点,一次只能容纳一个块。一元素焦点嵌入在四元素焦点中,用于选择要处理的单个块。例如,在考恩的“注意力焦点”中,四个数字可以同时出现在脑海中。当个人希望对每个数字进行处理时ーー例如,将数字2加到每个数字ーー需要对每个数字进行单独处理,因为大多数个人不能同时进行几个数学处理。奥伯奥尔的注意力部分选择其中一个数字进行处理,然后将注意力的焦点转移到下一个数字,一直持续到所有数字都被处理完毕。

Capacity

Working memory is widely acknowledged as having limited capacity. An early quantification of the capacity limit associated with short-term memory was the "magical number seven" suggested by Miller in 1956.[20] He claimed that the information-processing capacity of young adults is around seven elements, which he called "chunks", regardless of whether the elements are digits, letters, words, or other units. Later research revealed this number depends on the category of chunks used (e.g., span may be around seven for digits, six for letters, and five for words), and even on features of the chunks within a category. For instance, span is lower for long than short words. In general, memory span for verbal contents (digits, letters, words, etc.) depends on the phonological complexity of the content (i.e., the number of phonemes, the number of syllables),[21] and on the lexical status of the contents (whether the contents are words known to the person or not).[22] Several other factors affect a person's measured span, and therefore it is difficult to pin down the capacity of short-term or working memory to a number of chunks. Nonetheless, Cowan proposed that working memory has a capacity of about four chunks in young adults (and fewer in children and old adults).[23]

Working memory is widely acknowledged as having limited capacity. An early quantification of the capacity limit associated with short-term memory was the "magical number seven" suggested by Miller in 1956. He claimed that the information-processing capacity of young adults is around seven elements, which he called "chunks", regardless of whether the elements are digits, letters, words, or other units. Later research revealed this number depends on the category of chunks used (e.g., span may be around seven for digits, six for letters, and five for words), and even on features of the chunks within a category. For instance, span is lower for long than short words. In general, memory span for verbal contents (digits, letters, words, etc.) depends on the phonological complexity of the content (i.e., the number of phonemes, the number of syllables), and on the lexical status of the contents (whether the contents are words known to the person or not). Several other factors affect a person's measured span, and therefore it is difficult to pin down the capacity of short-term or working memory to a number of chunks. Nonetheless, Cowan proposed that working memory has a capacity of about four chunks in young adults (and fewer in children and old adults).

工作记忆被广泛认为容量有限。与短期记忆有关的容量限制的早期量化是米勒在1956年提出的“神奇数字7”。他声称年轻人的信息处理能力大约是七个元素,他称之为“块” ,不管这些元素是数字、字母、单词还是其他单位。后来的研究发现,这个数字取决于使用的组块的类别(例如,span 可能是7个数字,6个字母,5个单词) ,甚至取决于类别中组块的特征。例如,对于 long 而言,span 要低于 short 单词。一般来说,口头内容(数字、字母、单词等)的记忆广度这取决于内容的音系复杂性(即音素的数量,音节的数量) ,以及内容的词汇状态(内容是否是人们所知道的单词)。还有其他几个因素会影响一个人的测量广度,因此很难确定短时记忆或工作记忆的容量是多少。尽管如此,考恩提出,工作记忆在年轻人中的容量大约为四块(儿童和老年人的容量更小)。

Whereas most adults can repeat about seven digits in correct order, some individuals have shown impressive enlargements of their digit span—up to 80 digits. This feat is possible by extensive training on an encoding strategy by which the digits in a list are grouped (usually in groups of three to five) and these groups are encoded as a single unit (a chunk). For this to succeed, participants must be able to recognize the groups as some known string of digits. One person studied by Ericsson and his colleagues, for example, used an extensive knowledge of racing times from the history of sports in the process of coding chunks: several such chunks could then be combined into a higher-order chunk, forming a hierarchy of chunks. In this way, only some chunks at the highest level of the hierarchy must be retained in working memory, and for retrieval the chunks are unpacked. That is, the chunks in working memory act as retrieval cues that point to the digits they contain. Practicing memory skills such as these does not expand working memory capacity proper: it is the capacity to transfer (and retrieve) information from long-term memory that is improved, according to Ericsson and Kintsch (1995; see also Gobet & Simon, 2000[24]).

Whereas most adults can repeat about seven digits in correct order, some individuals have shown impressive enlargements of their digit span—up to 80 digits. This feat is possible by extensive training on an encoding strategy by which the digits in a list are grouped (usually in groups of three to five) and these groups are encoded as a single unit (a chunk). For this to succeed, participants must be able to recognize the groups as some known string of digits. One person studied by Ericsson and his colleagues, for example, used an extensive knowledge of racing times from the history of sports in the process of coding chunks: several such chunks could then be combined into a higher-order chunk, forming a hierarchy of chunks. In this way, only some chunks at the highest level of the hierarchy must be retained in working memory, and for retrieval the chunks are unpacked. That is, the chunks in working memory act as retrieval cues that point to the digits they contain. Practicing memory skills such as these does not expand working memory capacity proper: it is the capacity to transfer (and retrieve) information from long-term memory that is improved, according to Ericsson and Kintsch (1995; see also Gobet & Simon, 2000).

虽然大多数成年人能够正确地重复大约7个数字,但有些个人的数字跨度有令人印象深刻的扩大ーー达到80个数字。通过对编码策略的广泛培训,可以实现这一壮举。编码策略是将列表中的数字分组(通常为三到五个组) ,并将这些组编码为单个单元(一个块)。要实现这一点,参与者必须能够将组识别为某些已知的数字字符串。例如,埃里克森和他的同事研究的一个人,在编写代码块的过程中使用了来自体育运动历史的关于比赛时间的广泛知识: 几个这样的代码块可以组合成一个更高级的代码块,形成一个代码块的层次结构。这样,只有层次结构最高级别的一些块必须保留在工作内存中,并且为了检索这些块是解压缩的。也就是说,工作记忆中的记忆块作为提取线索,指向它们所包含的数字。根据 Ericsson 和 Kintsch (1995; 参见 Gobet & Simon,2000)的说法,练习这样的记忆技能并不能正确地扩展工作记忆容量: 它是从长期记忆中传递(和检索)信息的能力得到了提高。

Measures and correlates

Working memory capacity can be tested by a variety of tasks. A commonly used measure is a dual-task paradigm, combining a memory span measure with a concurrent processing task, sometimes referred to as "complex span". Daneman and Carpenter invented the first version of this kind of task, the "reading span", in 1980.[25] Subjects read a number of sentences (usually between two and six) and tried to remember the last word of each sentence. At the end of the list of sentences, they repeated back the words in their correct order. Other tasks that do not have this dual-task nature have also been shown to be good measures of working memory capacity.[26] Whereas Daneman and Carpenter believed that the combination of "storage" (maintenance) and processing is needed to measure working memory capacity, we know now that the capacity of working memory can be measured with short-term memory tasks that have no additional processing component.[27][28] Conversely, working memory capacity can also be measured with certain processing tasks that don't involve maintenance of information.[29][30] The question of what features a task must have to qualify as a good measure of working memory capacity is a topic of ongoing research.

Working memory capacity can be tested by a variety of tasks. A commonly used measure is a dual-task paradigm, combining a memory span measure with a concurrent processing task, sometimes referred to as "complex span". Daneman and Carpenter invented the first version of this kind of task, the "reading span", in 1980. Subjects read a number of sentences (usually between two and six) and tried to remember the last word of each sentence. At the end of the list of sentences, they repeated back the words in their correct order. Other tasks that do not have this dual-task nature have also been shown to be good measures of working memory capacity. Whereas Daneman and Carpenter believed that the combination of "storage" (maintenance) and processing is needed to measure working memory capacity, we know now that the capacity of working memory can be measured with short-term memory tasks that have no additional processing component. Conversely, working memory capacity can also be measured with certain processing tasks that don't involve maintenance of information. The question of what features a task must have to qualify as a good measure of working memory capacity is a topic of ongoing research.

工作记忆容量可以通过多种任务来测试。一个常用的度量方法是双任务范例,它将内存广度度量与并发处理任务(有时称为“复杂广度”)结合起来。丹曼和卡朋特在1980年发明了这类任务的第一个版本——“阅读跨度”。受试者阅读大量的句子(通常在两到六个之间) ,并试图记住每个句子的最后一个单词。在句子列表的最后,他们按照正确的顺序重复单词。其他没有这种双重任务性质的任务也被证明是工作记忆容量的良好措施。丹曼和卡朋特认为,工作记忆容量的测量需要“存储”(维护)和加工的结合,而我们现在知道,工作记忆的容量可以用没有额外加工成分的短时记忆任务来测量。相反,工作记忆容量也可以用不涉及信息维护的某些处理任务来衡量。工作记忆容量的衡量标准是什么,这是一个正在进行的研究课题。

Measures of working-memory capacity are strongly related to performance in other complex cognitive tasks, such as reading comprehension, problem solving, and with measures of intelligence quotient.[31]

Measures of working-memory capacity are strongly related to performance in other complex cognitive tasks, such as reading comprehension, problem solving, and with measures of intelligence quotient.

工作记忆容量的测量与其他复杂认知任务的表现密切相关,例如阅读理解、解决问题和智商。

Some researchers have argued[32] that working-memory capacity reflects the efficiency of executive functions, most notably the ability to maintain multiple task-relevant representations in the face of distracting irrelevant information; and that such tasks seem to reflect individual differences in the ability to focus and maintain attention, particularly when other events are serving to capture attention. Both working memory and executive functions rely strongly, though not exclusively, on frontal brain areas.[33]

Some researchers have argued that working-memory capacity reflects the efficiency of executive functions, most notably the ability to maintain multiple task-relevant representations in the face of distracting irrelevant information; and that such tasks seem to reflect individual differences in the ability to focus and maintain attention, particularly when other events are serving to capture attention. Both working memory and executive functions rely strongly, though not exclusively, on frontal brain areas.

一些研究人员认为,工作记忆容量反映了执行功能的效率,最明显的是面对分散注意力的不相关信息时保持多个任务相关表征的能力; 这些任务似乎反映了集中注意力和保持注意力能力的个体差异,特别是当其他事件有助于吸引注意力时。工作记忆和执行功能都强烈依赖额叶大脑区域,尽管并非完全如此。

Other researchers have argued that the capacity of working memory is better characterized as the ability to mentally form relations between elements, or to grasp relations in given information. This idea has been advanced, among others, by Graeme Halford, who illustrated it by our limited ability to understand statistical interactions between variables.[34] These authors asked people to compare written statements about the relations between several variables to graphs illustrating the same or a different relation, as in the following sentence: "If the cake is from France, then it has more sugar if it is made with chocolate than if it is made with cream, but if the cake is from Italy, then it has more sugar if it is made with cream than if it is made of chocolate". This statement describes a relation between three variables (country, ingredient, and amount of sugar), which is the maximum most individuals can understand. The capacity limit apparent here is obviously not a memory limit (all relevant information can be seen continuously) but a limit to how many relationships are discerned simultaneously.

Other researchers have argued that the capacity of working memory is better characterized as the ability to mentally form relations between elements, or to grasp relations in given information. This idea has been advanced, among others, by Graeme Halford, who illustrated it by our limited ability to understand statistical interactions between variables. These authors asked people to compare written statements about the relations between several variables to graphs illustrating the same or a different relation, as in the following sentence: "If the cake is from France, then it has more sugar if it is made with chocolate than if it is made with cream, but if the cake is from Italy, then it has more sugar if it is made with cream than if it is made of chocolate". This statement describes a relation between three variables (country, ingredient, and amount of sugar), which is the maximum most individuals can understand. The capacity limit apparent here is obviously not a memory limit (all relevant information can be seen continuously) but a limit to how many relationships are discerned simultaneously.

其他研究人员认为,工作记忆的能力更好的特征是在心理上形成元素之间的关系,或者在给定的信息中抓住关系。这个想法是由格雷姆 · 哈尔福德提出的,他用我们有限的能力来理解变量之间的统计交互作用来说明这一点。这些作者要求人们将关于几个变量之间关系的书面陈述与说明相同或不同关系的图表进行比较,例如下面这句话: ”如果蛋糕来自法国,那么用巧克力做的比用奶油做的含糖量高,但如果蛋糕来自意大利,那么用奶油做的比用巧克力做的含糖量高”。这个陈述描述了三个变量之间的关系(国家、成分和糖的数量) ,这是大多数人能够理解的最大值。这里显而易见的容量限制显然不是内存限制(所有相关信息都可以连续地看到) ,而是同时识别多少关系的限制。

Experimental studies of working-memory capacity

There are several hypotheses about the nature of the capacity limit. One is that a limited pool of cognitive resources is needed to keep representations active and thereby available for processing, and for carrying out processes.[35] Another hypothesis is that memory traces in working memory decay within a few seconds, unless refreshed through rehearsal, and because the speed of rehearsal is limited, we can maintain only a limited amount of information.[36] Yet another idea is that representations held in working memory interfere with each other.[37]

There are several hypotheses about the nature of the capacity limit. One is that a limited pool of cognitive resources is needed to keep representations active and thereby available for processing, and for carrying out processes. Another hypothesis is that memory traces in working memory decay within a few seconds, unless refreshed through rehearsal, and because the speed of rehearsal is limited, we can maintain only a limited amount of information. Yet another idea is that representations held in working memory interfere with each other.

关于容量极限的性质有几种假设。一个是需要有限的认知资源来保持表征活跃,从而可用于加工和执行过程。另一个假设是,工作记忆在几秒钟内衰退,除非通过复述刷新,并且由于复述的速度有限,我们只能保持有限的信息量。还有一种观点认为,工作记忆中的表征互相干扰。

Decay theories

The assumption that the contents of short-term or working memory decay over time, unless decay is prevented by rehearsal, goes back to the early days of experimental research on short-term memory.[38][39] It is also an important assumption in the multi-component theory of working memory.[40] The most elaborate decay-based theory of working memory to date is the "time-based resource sharing model".[41] This theory assumes that representations in working memory decay unless they are refreshed. Refreshing them requires an attentional mechanism that is also needed for any concurrent processing task. When there are small time intervals in which the processing task does not require attention, this time can be used to refresh memory traces. The theory therefore predicts that the amount of forgetting depends on the temporal density of attentional demands of the processing task—this density is called "cognitive load". The cognitive load depends on two variables, the rate at which the processing task requires individual steps to be carried out, and the duration of each step. For example, if the processing task consists of adding digits, then having to add another digit every half second places a higher cognitive load on the system than having to add another digit every two seconds. In a series of experiments, Barrouillet and colleagues have shown that memory for lists of letters depends neither on the number of processing steps nor the total time of processing but on cognitive load.[42]

The assumption that the contents of short-term or working memory decay over time, unless decay is prevented by rehearsal, goes back to the early days of experimental research on short-term memory. It is also an important assumption in the multi-component theory of working memory. The most elaborate decay-based theory of working memory to date is the "time-based resource sharing model". This theory assumes that representations in working memory decay unless they are refreshed. Refreshing them requires an attentional mechanism that is also needed for any concurrent processing task. When there are small time intervals in which the processing task does not require attention, this time can be used to refresh memory traces. The theory therefore predicts that the amount of forgetting depends on the temporal density of attentional demands of the processing task—this density is called "cognitive load". The cognitive load depends on two variables, the rate at which the processing task requires individual steps to be carried out, and the duration of each step. For example, if the processing task consists of adding digits, then having to add another digit every half second places a higher cognitive load on the system than having to add another digit every two seconds. In a series of experiments, Barrouillet and colleagues have shown that memory for lists of letters depends neither on the number of processing steps nor the total time of processing but on cognitive load.

短期记忆或工作记忆的内容会随着时间的推移而衰退,除非通过复述来防止衰退,这种假设可以追溯到短期记忆实验研究的早期。这也是工作记忆多分量理论中的一个重要假设。迄今为止,最详尽的基于衰减的工作记忆理论是“基于时间的资源共享模型”。这个理论假设工作记忆衰退中的表征除非被刷新。刷新它们需要注意力机制,这对于任何并发处理任务都是必需的。当处理任务不需要注意的时间间隔很小时,这个时间可以用来刷新记忆痕迹。因此,该理论预测,遗忘的数量取决于加工任务注意需求的时间密度,这种密度被称为“认知负荷”。认知负荷取决于两个变量,加工任务需要单个步骤执行的速度,以及每个步骤的持续时间。例如,如果处理任务包括添加数字,那么每半秒添加一个数字会比每两秒添加一个数字给系统带来更大的认知负荷。在一系列的实验中,Barrouillet 和他的同事已经证明了字母列表的记忆并不取决于处理步骤的数量或者处理的总时间,而是取决于认知负荷。

Resource theories

Resource theories assume that the capacity of working memory is a limited resource that must be shared between all representations that need to be maintained in working memory simultaneously.[43] Some resource theorists also assume that maintenance and concurrent processing share the same resource;[35] this can explain why maintenance is typically impaired by a concurrent processing demand. Resource theories have been very successful in explaining data from tests of working memory for simple visual features, such as colors or orientations of bars. An ongoing debate is whether the resource is a continuous quantity that can be subdivided among any number of items in working memory, or whether it consists of a small number of discrete "slots", each of which can be assigned to one memory item, so that only a limited number of about 3 items can be maintained in working memory at all.[44]

Resource theories assume that the capacity of working memory is a limited resource that must be shared between all representations that need to be maintained in working memory simultaneously. Some resource theorists also assume that maintenance and concurrent processing share the same resource;

资源理论认为工作记忆容量是一种有限的资源,必须在所有需要同时保存在工作记忆中的表征之间共享。一些资源理论家也假设维护和并发处理共享相同的资源;

Interference theories

Several forms of interference have been discussed by theorists. One of the oldest ideas is that new items simply replace older ones in working memory. Another form of interference is retrieval competition. For example, when the task is to remember a list of 7 words in their order, we need to start recall with the first word. While trying to retrieve the first word, the second word, which is represented in proximity, is accidentally retrieved as well, and the two compete for being recalled. Errors in serial recall tasks are often confusions of neighboring items on a memory list (so-called transpositions), showing that retrieval competition plays a role in limiting our ability to recall lists in order, and probably also in other working memory tasks. A third form of interference is the distortion of representations by superposition: When multiple representations are added on top of each other, each of them is blurred by the presence of all the others.[45] A fourth form of interference assumed by some authors is feature overwriting.[46][47] The idea is that each word, digit, or other item in working memory is represented as a bundle of features, and when two items share some features, one of them steals the features from the other. The more items are held in working memory, and the more their features overlap, the more each of them will be degraded by the loss of some features.

Several forms of interference have been discussed by theorists. One of the oldest ideas is that new items simply replace older ones in working memory. Another form of interference is retrieval competition. For example, when the task is to remember a list of 7 words in their order, we need to start recall with the first word. While trying to retrieve the first word, the second word, which is represented in proximity, is accidentally retrieved as well, and the two compete for being recalled. Errors in serial recall tasks are often confusions of neighboring items on a memory list (so-called transpositions), showing that retrieval competition plays a role in limiting our ability to recall lists in order, and probably also in other working memory tasks. A third form of interference is the distortion of representations by superposition: When multiple representations are added on top of each other, each of them is blurred by the presence of all the others. A fourth form of interference assumed by some authors is feature overwriting. The idea is that each word, digit, or other item in working memory is represented as a bundle of features, and when two items share some features, one of them steals the features from the other. The more items are held in working memory, and the more their features overlap, the more each of them will be degraded by the loss of some features.

理论家们讨论过几种形式的干涉。最古老的观点之一是,新的事物只是简单地取代了工作记忆中旧的事物。另一种形式的干扰是检索竞赛。例如,当任务是按顺序记住7个单词时,我们需要从第一个单词开始回忆。在试图检索第一个单词时,第二个单词也会意外地被检索到,这两个单词会争着被回忆起来。连续回忆任务中的错误通常是记忆列表中相邻项目的混淆(即所谓的换位) ,这表明提取竞争限制了我们按顺序回忆列表的能力,可能在其他工作记忆任务中也是如此。第三种形式的干涉是叠加对表象的扭曲: 当多重表象叠加在一起时,每一种表象都会因为所有其他表象的存在而模糊不清。一些作者认为的第四种干扰形式是特征覆盖。这个想法是,工作记忆中的每个单词、数字或其他项目都被表示为一系列特征,当两个项目共享某些特征时,其中一个就会窃取另一个的特征。工作记忆中保存的条目越多,它们之间的特征重叠越多,每个条目由于某些特征的丢失而降低的程度就越大。

Limitations

None of these hypotheses can explain the experimental data entirely. The resource hypothesis, for example, was meant to explain the trade-off between maintenance and processing: The more information must be maintained in working memory, the slower and more error prone concurrent processes become, and with a higher demand on concurrent processing memory suffers. This trade-off has been investigated by tasks like the reading-span task described above. It has been found that the amount of trade-off depends on the similarity of the information to be remembered and the information to be processed. For example, remembering numbers while processing spatial information, or remembering spatial information while processing numbers, impair each other much less than when material of the same kind must be remembered and processed.[48] Also, remembering words and processing digits, or remembering digits and processing words, is easier than remembering and processing materials of the same category.[49] These findings are also difficult to explain for the decay hypothesis, because decay of memory representations should depend only on how long the processing task delays rehearsal or recall, not on the content of the processing task. A further problem for the decay hypothesis comes from experiments in which the recall of a list of letters was delayed, either by instructing participants to recall at a slower pace, or by instructing them to say an irrelevant word once or three times in between recall of each letter. Delaying recall had virtually no effect on recall accuracy.[50][51] The interference theory seems to fare best with explaining why the similarity between memory contents and the contents of concurrent processing tasks affects how much they impair each other. More similar materials are more likely to be confused, leading to retrieval competition.

None of these hypotheses can explain the experimental data entirely. The resource hypothesis, for example, was meant to explain the trade-off between maintenance and processing: The more information must be maintained in working memory, the slower and more error prone concurrent processes become, and with a higher demand on concurrent processing memory suffers. This trade-off has been investigated by tasks like the reading-span task described above. It has been found that the amount of trade-off depends on the similarity of the information to be remembered and the information to be processed. For example, remembering numbers while processing spatial information, or remembering spatial information while processing numbers, impair each other much less than when material of the same kind must be remembered and processed. Also, remembering words and processing digits, or remembering digits and processing words, is easier than remembering and processing materials of the same category. These findings are also difficult to explain for the decay hypothesis, because decay of memory representations should depend only on how long the processing task delays rehearsal or recall, not on the content of the processing task. A further problem for the decay hypothesis comes from experiments in which the recall of a list of letters was delayed, either by instructing participants to recall at a slower pace, or by instructing them to say an irrelevant word once or three times in between recall of each letter. Delaying recall had virtually no effect on recall accuracy. The interference theory seems to fare best with explaining why the similarity between memory contents and the contents of concurrent processing tasks affects how much they impair each other. More similar materials are more likely to be confused, leading to retrieval competition.

这些假说都不能完全解释实验数据。例如,资源假说旨在解释维护和加工之间的权衡: 工作记忆中必须保存的信息越多,并发过程就变得越慢、越容易出错,同时对并发加工记忆的要求也越高。这种权衡已经通过上面描述的阅读跨度任务等任务进行了研究。研究发现,权衡的数量取决于要记忆的信息和要处理的信息的相似性。例如,在处理空间信息时记忆数字,或者在处理数字时记忆空间信息,这些都比同类材料必须记忆和处理时相互影响小得多。此外,记忆单词和处理数字,或者记忆数字和处理单词,比记忆和处理同一类别的材料更容易。这些发现对于衰退假说也很难解释,因为记忆表征的衰退只取决于加工任务延迟复述或回忆的时间,而不取决于加工任务的内容。衰退假说的另一个问题来自于延迟回忆一个字母列表的实验,要么是指示参与者以较慢的速度回忆,要么是指示他们在回忆每个字母之间说一个不相关的单词一次或三次。延迟回忆对回忆准确率几乎没有影响。干扰理论似乎最好地解释了为什么内存内容和同时处理的任务内容之间的相似性会影响它们彼此之间的损害程度。越多的相似材料越容易混淆,导致检索竞争。

Development

The capacity of working memory increases gradually over childhood[52] and declines gradually in old age.[53]

The capacity of working memory increases gradually over childhood and declines gradually in old age.

工作记忆容量随儿童时期逐渐增加,随着年龄的增长逐渐下降。

Childhood

Measures of performance on tests of working memory increase continuously between early childhood and adolescence, while the structure of correlations between different tests remains largely constant.[52] Starting with work in the Neo-Piagetian tradition,[54][55] theorists have argued that the growth of working-memory capacity is a major driving force of cognitive development. This hypothesis has received substantial empirical support from studies showing that the capacity of working memory is a strong predictor of cognitive abilities in childhood.[56] Particularly strong evidence for a role of working memory for development comes from a longitudinal study showing that working-memory capacity at one age predicts reasoning ability at a later age.[57] Studies in the Neo-Piagetian tradition have added to this picture by analyzing the complexity of cognitive tasks in terms of the number of items or relations that have to be considered simultaneously for a solution. Across a broad range of tasks, children manage task versions of the same level of complexity at about the same age, consistent with the view that working memory capacity limits the complexity they can handle at a given age.[58] Although neuroscience studies support the notion that children rely on prefrontal cortex for performing various working memory tasks, an fMRI meta-analysis on children compared to adults performing the n back task revealed lack of consistent prefrontal cortex activation in children, while posterior regions including the insular cortex and cerebellum remain intact.[59]

Measures of performance on tests of working memory increase continuously between early childhood and adolescence, while the structure of correlations between different tests remains largely constant. theorists have argued that the growth of working-memory capacity is a major driving force of cognitive development. This hypothesis has received substantial empirical support from studies showing that the capacity of working memory is a strong predictor of cognitive abilities in childhood. Particularly strong evidence for a role of working memory for development comes from a longitudinal study showing that working-memory capacity at one age predicts reasoning ability at a later age. Studies in the Neo-Piagetian tradition have added to this picture by analyzing the complexity of cognitive tasks in terms of the number of items or relations that have to be considered simultaneously for a solution. Across a broad range of tasks, children manage task versions of the same level of complexity at about the same age, consistent with the view that working memory capacity limits the complexity they can handle at a given age. Although neuroscience studies support the notion that children rely on prefrontal cortex for performing various working memory tasks, an fMRI meta-analysis on children compared to adults performing the n back task revealed lack of consistent prefrontal cortex activation in children, while posterior regions including the insular cortex and cerebellum remain intact.

工作记忆测试的成绩在儿童早期和青少年期间不断增加,而不同测试之间的相关性结构基本保持不变。理论家认为工作记忆容量的增长是认知发展的主要驱动力。这一假设得到了大量实证研究的支持,研究表明工作记忆能力是童年认知能力的一个强有力的预测因子。特别强有力的证据表明工作记忆对于发展有一定的作用,来自于一项追踪研究研究,该研究表明,一个年龄段的工作记忆能力预示着以后年龄段的推理能力。对新皮亚杰传统的研究通过分析认知任务的复杂性(需要同时考虑的项目或关系的数量)增加了这一图景。在一系列广泛的任务中,儿童在相同的年龄处理同等复杂程度的任务,这与工作记忆容量限制了他们在特定年龄能够处理的复杂程度的观点一致。虽然神经科学研究支持儿童依靠脑前额叶外皮来完成各种工作记忆任务的观点,但是一项功能磁共振成像元分析对比了儿童和成年人的 n back 任务,发现儿童缺乏持续的脑前额叶外皮激活,而后部区域包括岛叶皮质和小脑仍然完好无损。

Aging

Working memory is among the cognitive functions most sensitive to decline in old age.[60][61] Several explanations have been offered for this decline in psychology. One is the processing speed theory of cognitive aging by Tim Salthouse.[62] Drawing on the finding of general slowing of cognitive processes as people grow older, Salthouse argues that slower processing leaves more time for working-memory contents to decay, thus reducing effective capacity. However, the decline of working-memory capacity cannot be entirely attributed to slowing because capacity declines more in old age than speed.[61][63] Another proposal is the inhibition hypothesis advanced by Lynn Hasher and Rose Zacks.[64] This theory assumes a general deficit in old age in the ability to inhibit irrelevant, or no-longer relevant, information. Therefore, working memory tends to be cluttered with irrelevant contents that reduce the effective capacity for relevant content. The assumption of an inhibition deficit in old age has received much empirical support[65] but, so far, it is not clear whether the decline in inhibitory ability fully explains the decline of working-memory capacity. An explanation on the neural level of the decline of working memory and other cognitive functions in old age has been proposed by West.[66] She argued that working memory depends to a large degree on the pre-frontal cortex, which deteriorates more than other brain regions as we grow old. Age related decline in working memory can be briefly reversed using low intensity transcranial stimulation, synchronizing rhythms in bilateral frontal and left temporal lobe areas.[67]

Working memory is among the cognitive functions most sensitive to decline in old age. Several explanations have been offered for this decline in psychology. One is the processing speed theory of cognitive aging by Tim Salthouse. Drawing on the finding of general slowing of cognitive processes as people grow older, Salthouse argues that slower processing leaves more time for working-memory contents to decay, thus reducing effective capacity. However, the decline of working-memory capacity cannot be entirely attributed to slowing because capacity declines more in old age than speed. Another proposal is the inhibition hypothesis advanced by Lynn Hasher and Rose Zacks. This theory assumes a general deficit in old age in the ability to inhibit irrelevant, or no-longer relevant, information. Therefore, working memory tends to be cluttered with irrelevant contents that reduce the effective capacity for relevant content. The assumption of an inhibition deficit in old age has received much empirical support but, so far, it is not clear whether the decline in inhibitory ability fully explains the decline of working-memory capacity. An explanation on the neural level of the decline of working memory and other cognitive functions in old age has been proposed by West. She argued that working memory depends to a large degree on the pre-frontal cortex, which deteriorates more than other brain regions as we grow old. Age related decline in working memory can be briefly reversed using low intensity transcranial stimulation, synchronizing rhythms in bilateral frontal and left temporal lobe areas.

工作记忆是认知功能中对老年衰退最敏感的部分。对于这种心理学的衰退,有几种解释。一个是提姆 · 萨尔特豪斯的认知老化加工速度理论。随着年龄的增长,人们的认知过程普遍变慢。萨尔豪斯利用这一发现,认为缓慢的处理过程会留下更多的时间让工作记忆内容衰减,从而降低有效容量。然而,工作记忆容量的下降不能完全归因于慢,因为容量下降更多的是在老年而不是速度。另一个提议是 Lynn Hasher 和 Rose Zacks 提出的抑制假说。这个理论假设老年人在抑制不相关或不再相关的信息方面普遍缺乏能力。因此,工作记忆往往被不相关的内容所干扰,从而降低了相关内容的有效容量。老年抑制能力缺失的假设得到了大量实证研究的支持,但到目前为止,抑制能力的下降是否完全解释了工作记忆能力的下降尚不清楚。韦斯特对老年人工作记忆和其他认知功能衰退的神经机制提出了解释。她认为,工作记忆在很大程度上取决于前额叶皮层,随着年龄的增长,前额叶皮层比其他大脑区域更容易衰退。通过低强度经颅刺激,双侧额叶和左侧颞叶同步节律,年龄相关的工作记忆衰退可以短暂逆转。

Training

Torkel Klingberg was the first to investigate whether intensive training of working memory has beneficial effects on other cognitive functions. His pioneering study suggested that working memory can be improved by training in ADHD patients through computerized programs.[68] This study has found that a period of working memory training increases a range of cognitive abilities and increases IQ test scores. Another study of the same group[69] has shown that, after training, measured brain activity related to working memory increased in the prefrontal cortex, an area that many researchers have associated with working memory functions. It has been shown in one study that working memory training increases the density of prefrontal and parietal dopamine receptors (specifically, DRD1) in test persons.[70] However, subsequent work with the same training program has failed to replicate the beneficial effects of training on cognitive performance. A meta-analytic summary of research with Klingberg's training program up to 2011 shows that this training has at best a negligible effect on tests of intelligence and of attention[71]

Torkel Klingberg was the first to investigate whether intensive training of working memory has beneficial effects on other cognitive functions. His pioneering study suggested that working memory can be improved by training in ADHD patients through computerized programs. This study has found that a period of working memory training increases a range of cognitive abilities and increases IQ test scores. Another study of the same group has shown that, after training, measured brain activity related to working memory increased in the prefrontal cortex, an area that many researchers have associated with working memory functions. It has been shown in one study that working memory training increases the density of prefrontal and parietal dopamine receptors (specifically, DRD1) in test persons. However, subsequent work with the same training program has failed to replicate the beneficial effects of training on cognitive performance. A meta-analytic summary of research with Klingberg's training program up to 2011 shows that this training has at best a negligible effect on tests of intelligence and of attention

托克尔 · 克林伯格是第一个研究工作记忆强化训练是否对其他认知功能有益的人。他的开创性研究表明,通过电脑程序训练 ADHD 患者的工作记忆能够得到改善。这项研究发现,一段时间的工作记忆训练可以提高一系列的认知能力,并提高 IQ 测试成绩。另一项针对同一群体的研究表明,经过训练后,测量的与工作记忆有关的大脑活动在脑前额叶外皮中增加了,这个区域被许多研究人员与工作记忆功能联系在一起。一项研究表明,工作记忆训练增加了受试者的前额叶和顶叶多巴胺受体(特别是 DRD1)的密度。然而,后续的工作与同样的训练计划已经无法复制训练对认知表现的有益影响。克林伯格2011年之前的训练计划的研究的元分析总结表明,这种训练在智力和注意力测试中充其量只有微不足道的效果

In another influential study, training with a working memory task (the dual n-back task) has improved performance on a fluid intelligence test in healthy young adults.[72] The improvement of fluid intelligence by training with the n-back task was replicated in 2010,[73] but two studies published in 2012 failed to reproduce the effect.[74][75] The combined evidence from about 30 experimental studies on the effectiveness of working-memory training has been evaluated by several meta-analyses.[76][77] The authors of these meta-analyses disagree in their conclusions as to whether or not working-memory training improves intelligence. Yet, these meta-analyses agree in their estimate of the size of the effect of working-memory training: If there is such an effect, it is likely to be small.

In another influential study, training with a working memory task (the dual n-back task) has improved performance on a fluid intelligence test in healthy young adults. The improvement of fluid intelligence by training with the n-back task was replicated in 2010, but two studies published in 2012 failed to reproduce the effect. The combined evidence from about 30 experimental studies on the effectiveness of working-memory training has been evaluated by several meta-analyses. The authors of these meta-analyses disagree in their conclusions as to whether or not working-memory training improves intelligence. Yet, these meta-analyses agree in their estimate of the size of the effect of working-memory training: If there is such an effect, it is likely to be small.

在另一项有影响力的研究中,工作记忆任务(双 n-back 任务)训练提高了健康年轻人在流体智力测试中的表现。2010年重复了通过 n-back 任务训练提高流体智力的实验,但2012年发表的两项研究未能重现这一效果。大约30个关于工作记忆训练有效性的实验研究的综合证据已经被一些元分析评估。关于工作记忆训练是否能提高智力,这些元分析的作者不同意他们的结论。然而,这些元分析对工作记忆训练效果的估计是一致的: 如果有这样的效果,那么它可能是很小的。

In the brain

Neural mechanisms of maintaining information

The first insights into the neuronal and neurotransmitter basis of working memory came from animal research. The work of Jacobsen[78] and Fulton in the 1930s first showed that lesions to the PFC impaired spatial working memory performance in monkeys. The later work of Joaquin Fuster[79] recorded the electrical activity of neurons in the PFC of monkeys while they were doing a delayed matching task. In that task, the monkey sees how the experimenter places a bit of food under one of two identical-looking cups. A shutter is then lowered for a variable delay period, screening off the cups from the monkey's view. After the delay, the shutter opens and the monkey is allowed to retrieve the food from under the cups. Successful retrieval in the first attempt – something the animal can achieve after some training on the task – requires holding the location of the food in memory over the delay period. Fuster found neurons in the PFC that fired mostly during the delay period, suggesting that they were involved in representing the food location while it was invisible. Later research has shown similar delay-active neurons also in the posterior parietal cortex, the thalamus, the caudate, and the globus pallidus.[80] The work of Goldman-Rakic and others showed that principal sulcal, dorsolateral PFC interconnects with all of these brain regions, and that neuronal microcircuits within PFC are able to maintain information in working memory through recurrent excitatory glutamate networks of pyramidal cells that continue to fire throughout the delay period.[81] These circuits are tuned by lateral inhibition from GABAergic interneurons.[82] The neuromodulatory arousal systems markedly alter PFC working memory function; for example, either too little or too much dopamine or norepinephrine impairs PFC network firing[83] and working memory performance.[84]

The first insights into the neuronal and neurotransmitter basis of working memory came from animal research. The work of Jacobsen and Fulton in the 1930s first showed that lesions to the PFC impaired spatial working memory performance in monkeys. The later work of Joaquin Fuster recorded the electrical activity of neurons in the PFC of monkeys while they were doing a delayed matching task. In that task, the monkey sees how the experimenter places a bit of food under one of two identical-looking cups. A shutter is then lowered for a variable delay period, screening off the cups from the monkey's view. After the delay, the shutter opens and the monkey is allowed to retrieve the food from under the cups. Successful retrieval in the first attempt – something the animal can achieve after some training on the task – requires holding the location of the food in memory over the delay period. Fuster found neurons in the PFC that fired mostly during the delay period, suggesting that they were involved in representing the food location while it was invisible. Later research has shown similar delay-active neurons also in the posterior parietal cortex, the thalamus, the caudate, and the globus pallidus. The work of Goldman-Rakic and others showed that principal sulcal, dorsolateral PFC interconnects with all of these brain regions, and that neuronal microcircuits within PFC are able to maintain information in working memory through recurrent excitatory glutamate networks of pyramidal cells that continue to fire throughout the delay period. These circuits are tuned by lateral inhibition from GABAergic interneurons. The neuromodulatory arousal systems markedly alter PFC working memory function; for example, either too little or too much dopamine or norepinephrine impairs PFC network firing and working memory performance.

对工作记忆的神经元和神经递质基础的第一次见解来自动物研究。雅各布森和富尔顿在20世纪30年代的研究首次表明,对 PFC 的损害损害了猴子的空间工作记忆能力。后来,华金 · 福斯特的工作记录了猴子在完成延迟匹配任务时 PFC 中神经元的电活动。在这个任务中,猴子看到实验者是如何把一点食物放在两个看起来一模一样的杯子下面的。然后,一个快门降低一个可变的延迟时间,屏蔽掉猴子的视线。在延迟之后,快门打开,猴子可以从杯子下面取出食物。在第一次尝试中成功地提取食物——这是动物经过一些训练后能够完成的任务——需要在延迟期内保持食物在记忆中的位置。福斯特发现 PFC 中的神经元在延迟期间大部分被激活,这表明他们参与了食物位置的表现,而食物位置是看不见的。后来的研究表明,后顶叶皮层、丘脑、尾状核和苍白球也有类似的延迟活动神经元。Goldman-Rakic 等人的研究表明,脊髓背外侧的 PFC 与所有这些大脑区域相互连接,PFC 内的神经元微回路能够通过反复兴奋的锥体细胞谷氨酸网络来维持工作记忆中的信息,这些神经元网络在整个延迟期间持续激活。这些回路是由 gaba 能中间神经元的侧抑制调节的。神经调节性唤起系统显著改变 PFC 工作记忆功能; 例如,过多或过少的多巴胺或去甲肾上腺素损害 PFC 神经网络的放电和工作记忆的表现。

The research described above on persistent firing of certain neurons in the delay period of working memory tasks shows that the brain has a mechanism of keeping representations active without external input. Keeping representations active, however, is not enough if the task demands maintaining more than one chunk of information. In addition, the components and features of each chunk must be bound together to prevent them from being mixed up. For example, if a red triangle and a green square must be remembered at the same time, one must make sure that "red" is bound to "triangle" and "green" is bound to "square". One way of establishing such bindings is by having the neurons that represent features of the same chunk fire in synchrony, and those that represent features belonging to different chunks fire out of sync.[85] In the example, neurons representing redness would fire in synchrony with neurons representing the triangular shape, but out of sync with those representing the square shape. So far, there is no direct evidence that working memory uses this binding mechanism, and other mechanisms have been proposed as well.[86] It has been speculated that synchronous firing of neurons involved in working memory oscillate with frequencies in the theta band (4 to 8 Hz). Indeed, the power of theta frequency in the EEG increases with working memory load,[87] and oscillations in the theta band measured over different parts of the skull become more coordinated when the person tries to remember the binding between two components of information.[88]

The research described above on persistent firing of certain neurons in the delay period of working memory tasks shows that the brain has a mechanism of keeping representations active without external input. Keeping representations active, however, is not enough if the task demands maintaining more than one chunk of information. In addition, the components and features of each chunk must be bound together to prevent them from being mixed up. For example, if a red triangle and a green square must be remembered at the same time, one must make sure that "red" is bound to "triangle" and "green" is bound to "square". One way of establishing such bindings is by having the neurons that represent features of the same chunk fire in synchrony, and those that represent features belonging to different chunks fire out of sync. In the example, neurons representing redness would fire in synchrony with neurons representing the triangular shape, but out of sync with those representing the square shape. So far, there is no direct evidence that working memory uses this binding mechanism, and other mechanisms have been proposed as well. It has been speculated that synchronous firing of neurons involved in working memory oscillate with frequencies in the theta band (4 to 8 Hz). Indeed, the power of theta frequency in the EEG increases with working memory load, and oscillations in the theta band measured over different parts of the skull become more coordinated when the person tries to remember the binding between two components of information.

上述关于工作记忆任务延迟期间某些神经元持续放电的研究表明,大脑有一种在没有外部输入的情况下保持表征活跃的机制。然而,如果任务需要维护多个信息块,仅仅保持表示活动是不够的。此外,必须将每个块的组件和特性绑定在一起,以防止它们混在一起。例如,如果必须同时记住一个红色三角形和一个绿色正方形,就必须确保“红色”与“三角形”绑定,而“绿色”与“正方形”绑定。建立这种结合的一种方法是让神经元以同步的方式表现同一块发出的特征,而那些表现不同块发出的特征的神经元则同步发出。在这个例子中,代表红色的神经元会与代表三角形的神经元同步激发,但与代表正方形的神经元不同步。到目前为止,还没有直接的证据表明工作记忆使用这种结合机制,其他机制也被提出。据推测,与工作记忆有关的神经元的同步放电在 θ 波段(4ー8赫兹)振荡。事实上,脑电图中 θ 频率的力量随着工作记忆负荷的增加而增加,当人们试图记住信息的两个组成部分之间的联系时,在头骨不同部位测量到的 θ 波段的振荡变得更加协调。

Localization in the brain

Localization of brain functions in humans has become much easier with the advent of brain imaging methods (PET and fMRI). This research has confirmed that areas in the PFC are involved in working memory functions. During the 1990s much debate has centered on the different functions of the ventrolateral (i.e., lower areas) and the dorsolateral (higher) areas of the PFC. A human lesion study provides additional evidence for the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in working memory.[89] One view was that the dorsolateral areas are responsible for spatial working memory and the ventrolateral areas for non-spatial working memory. Another view proposed a functional distinction, arguing that ventrolateral areas are mostly involved in pure maintenance of information, whereas dorsolateral areas are more involved in tasks requiring some processing of the memorized material. The debate is not entirely resolved but most of the evidence supports the functional distinction.[90]

Localization of brain functions in humans has become much easier with the advent of brain imaging methods (PET and fMRI). This research has confirmed that areas in the PFC are involved in working memory functions. During the 1990s much debate has centered on the different functions of the ventrolateral (i.e., lower areas) and the dorsolateral (higher) areas of the PFC. A human lesion study provides additional evidence for the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in working memory. One view was that the dorsolateral areas are responsible for spatial working memory and the ventrolateral areas for non-spatial working memory. Another view proposed a functional distinction, arguing that ventrolateral areas are mostly involved in pure maintenance of information, whereas dorsolateral areas are more involved in tasks requiring some processing of the memorized material. The debate is not entirely resolved but most of the evidence supports the functional distinction.

随着脑成像方法(PET 和 fMRI)的出现,人脑功能的定位变得更加容易。这项研究已经证实了 PFC 的某些区域与工作记忆功能有关。在20世纪90年代,很多争论都集中在腹外侧区(即较低区域)和背外侧区(较高区域)的不同功能上。一项人体损伤研究为背外侧脑前额叶外皮在工作记忆中的作用提供了额外的证据。一种观点认为,背外侧区负责空间工作记忆,腹外侧区负责非空间工作记忆。另一种观点提出了功能区分,认为腹外侧区域主要涉及纯粹的信息维护,而背外侧区域则更多涉及需要对记忆材料进行某些处理的任务。争论并没有完全解决,但大多数证据支持功能区分。

Brain imaging has revealed that working memory functions are not limited to the PFC. A review of numerous studies[91] shows areas of activation during working memory tasks scattered over a large part of the cortex. There is a tendency for spatial tasks to recruit more right-hemisphere areas, and for verbal and object working memory to recruit more left-hemisphere areas. The activation during verbal working memory tasks can be broken down into one component reflecting maintenance, in the left posterior parietal cortex, and a component reflecting subvocal rehearsal, in the left frontal cortex (Broca's area, known to be involved in speech production).[92]

Brain imaging has revealed that working memory functions are not limited to the PFC. A review of numerous studies shows areas of activation during working memory tasks scattered over a large part of the cortex. There is a tendency for spatial tasks to recruit more right-hemisphere areas, and for verbal and object working memory to recruit more left-hemisphere areas. The activation during verbal working memory tasks can be broken down into one component reflecting maintenance, in the left posterior parietal cortex, and a component reflecting subvocal rehearsal, in the left frontal cortex (Broca's area, known to be involved in speech production).

脑成像显示,工作记忆功能并不局限于 pfc。大量研究的综述表明,工作记忆任务中的激活区域分散在大脑皮层的很大一部分。空间任务倾向于招募更多的右半球区域,言语和物体工作记忆倾向于招募更多的左半球区域。非文字工作记忆任务中的激活可以分解为左后顶叶皮层反映维持的一个组成部分,以及左额叶皮层反映次声练习的一个组成部分(已知与语言产生有关的 Broca 区域)。

There is an emerging consensus that most working memory tasks recruit a network of PFC and parietal areas. A study has shown that during a working memory task the connectivity between these areas increases.[93] Another study has demonstrated that these areas are necessary for working memory, and not simply activated accidentally during working memory tasks, by temporarily blocking them through transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), thereby producing an impairment in task performance.[94]

There is an emerging consensus that most working memory tasks recruit a network of PFC and parietal areas. A study has shown that during a working memory task the connectivity between these areas increases. Another study has demonstrated that these areas are necessary for working memory, and not simply activated accidentally during working memory tasks, by temporarily blocking them through transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), thereby producing an impairment in task performance.

大多数工作记忆任务是由 PFC 和顶叶区域组成的网络,这一点正在形成共识。一项研究表明,在工作记忆任务中,这些区域之间的连通性增加了。另一项研究表明,这些区域是工作记忆的必要组成部分,而不是简单地在工作记忆任务中通过暂时性地阻塞它们而被意外激活,从而导致任务表现受损。这项研究发表在《经颅磁力刺激志上。

A current debate concerns the function of these brain areas. The PFC has been found to be active in a variety of tasks that require executive functions.[33] This has led some researchers to argue that the role of PFC in working memory is in controlling attention, selecting strategies, and manipulating information in working memory, but not in maintenance of information. The maintenance function is attributed to more posterior areas of the brain, including the parietal cortex.[95][96] Other authors interpret the activity in parietal cortex as reflecting executive functions, because the same area is also activated in other tasks requiring attention but not memory.[97]

A current debate concerns the function of these brain areas. The PFC has been found to be active in a variety of tasks that require executive functions. Other authors interpret the activity in parietal cortex as reflecting executive functions, because the same area is also activated in other tasks requiring attention but not memory.

目前的争论是关于这些大脑区域的功能。研究发现,PFC 在许多需要执行功能的任务中表现活跃。其他作者解释说,顶叶皮层的活动反映了执行功能,因为同一区域在其他需要注意力而不是记忆的任务中也被激活。

A 2003 meta-analysis of 60 neuroimaging studies found left frontal cortex was involved in low-task demand verbal working memory and right frontal cortex for spatial working memory. Brodmann's areas (BAs) 6, 8, and 9, in the superior frontal cortex was involved when working memory must be continuously updated and when memory for temporal order had to be maintained. Right Brodmann 10 and 47 in the ventral frontal cortex were involved more frequently with demand for manipulation such as dual-task requirements or mental operations, and Brodmann 7 in the posterior parietal cortex was also involved in all types of executive function.[98]

A 2003 meta-analysis of 60 neuroimaging studies found left frontal cortex was involved in low-task demand verbal working memory and right frontal cortex for spatial working memory. Brodmann's areas (BAs) 6, 8, and 9, in the superior frontal cortex was involved when working memory must be continuously updated and when memory for temporal order had to be maintained. Right Brodmann 10 and 47 in the ventral frontal cortex were involved more frequently with demand for manipulation such as dual-task requirements or mental operations, and Brodmann 7 in the posterior parietal cortex was also involved in all types of executive function.

2003年对60项神经成像研究的荟萃分析发现,左额叶皮层参与了低任务需求的语言工作记忆,而右额叶皮层参与了空间工作记忆。当工作记忆必须不断更新和时间顺序记忆必须保持时,Brodmann 大脑上额叶皮层区域(BAs)6、8、9区域参与其中。腹侧额叶皮层的右布罗德曼10和47参与双重任务要求或心理操作等操作的频率较高,后顶叶皮层的布罗德曼7参与了所有类型的执行功能。

Working memory has been suggested to involve two processes with different neuroanatomical locations in the frontal and parietal lobes.[99] First, a selection operation that retrieves the most relevant item, and second an updating operation that changes the focus of attention made upon it. Updating the attentional focus has been found to involve the transient activation in the caudal superior frontal sulcus and posterior parietal cortex, while increasing demands on selection selectively changes activation in the rostral superior frontal sulcus and posterior cingulate/precuneus.[99]

Working memory has been suggested to involve two processes with different neuroanatomical locations in the frontal and parietal lobes. First, a selection operation that retrieves the most relevant item, and second an updating operation that changes the focus of attention made upon it. Updating the attentional focus has been found to involve the transient activation in the caudal superior frontal sulcus and posterior parietal cortex, while increasing demands on selection selectively changes activation in the rostral superior frontal sulcus and posterior cingulate/precuneus.

工作记忆被认为涉及额叶和顶叶神经解剖位置不同的两个突起。首先是检索最相关项的选择操作,其次是更改关注焦点的更新操作。更新注意焦点包括额上沟尾部和后顶叶皮质的短暂激活,而对选择性选择的需求增加则改变了额上沟和后扣带回/楔前叶的激活。

Articulating the differential function of brain regions involved in working memory is dependent on tasks able to distinguish these functions.[100] Most brain imaging studies of working memory have used recognition tasks such as delayed recognition of one or several stimuli, or the n-back task, in which each new stimulus in a long series must be compared to the one presented n steps back in the series. The advantage of recognition tasks is that they require minimal movement (just pressing one of two keys), making fixation of the head in the scanner easier. Experimental research and research on individual differences in working memory, however, has used largely recall tasks (e.g., the reading span task, see below). It is not clear to what degree recognition and recall tasks reflect the same processes and the same capacity limitations.

Articulating the differential function of brain regions involved in working memory is dependent on tasks able to distinguish these functions. Most brain imaging studies of working memory have used recognition tasks such as delayed recognition of one or several stimuli, or the n-back task, in which each new stimulus in a long series must be compared to the one presented n steps back in the series. The advantage of recognition tasks is that they require minimal movement (just pressing one of two keys), making fixation of the head in the scanner easier. Experimental research and research on individual differences in working memory, however, has used largely recall tasks (e.g., the reading span task, see below). It is not clear to what degree recognition and recall tasks reflect the same processes and the same capacity limitations.

阐明与工作记忆有关的大脑区域的不同功能取决于能够区分这些功能的任务。大多数关于工作记忆的脑成像研究都使用了识别任务,比如延迟识别一个或多个刺激,或 n-back 任务,在这个任务中,一个长系列中的每个新刺激都必须与该系列中的一个 n 步后的刺激进行比较。识别任务的优势在于,它们只需要最少的运动(只需按两个键中的一个) ,使得在扫描仪中头部的固定更加容易。然而,关于工作记忆个体差异的实验研究已经大量使用了回忆任务(例如,阅读跨度任务,见下文)。目前尚不清楚识别和回忆任务在多大程度上反映了相同的过程和相同的能力限制。

Brain imaging studies have been conducted with the reading span task or related tasks. Increased activation during these tasks was found in the PFC and, in several studies, also in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). People performing better on the task showed larger increase of activation in these areas, and their activation was correlated more over time, suggesting that their neural activity in these two areas was better coordinated, possibly due to stronger connectivity.[101][102]

Brain imaging studies have been conducted with the reading span task or related tasks. Increased activation during these tasks was found in the PFC and, in several studies, also in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). People performing better on the task showed larger increase of activation in these areas, and their activation was correlated more over time, suggesting that their neural activity in these two areas was better coordinated, possibly due to stronger connectivity.

脑成像研究已经与阅读广度任务或相关任务进行。在这些任务中,PFC 和一些研究发现前扣带皮层(ACC)的激活增强。在任务中表现更好的人在这些区域表现出更大的激活增加,随着时间的推移,他们的激活相关性更强,这表明他们这两个区域的神经活动更好地协调,可能是由于更强的连接性。

Neural models

One approach to modeling the neurophysiology and the functioning of working memory is prefrontal cortex basal ganglia working memory (PBWM). In this model, the prefrontal cortex works hand-in-hand with the basal ganglia to accomplish the tasks of working memory. Many studies have shown this to be the case.[103] One used ablation techniques in patients who had suffered from seizures and had damage to the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia.[104] Researchers found that such damage resulted in decreased capacity to carry out the executive function of working memory.[104] Additional research conducted on patients with brain alterations due to methamphetamine use found that training working memory increases volume in the basal ganglia.[105]

One approach to modeling the neurophysiology and the functioning of working memory is prefrontal cortex basal ganglia working memory (PBWM). In this model, the prefrontal cortex works hand-in-hand with the basal ganglia to accomplish the tasks of working memory. Many studies have shown this to be the case. One used ablation techniques in patients who had suffered from seizures and had damage to the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia. Additional research conducted on patients with brain alterations due to methamphetamine use found that training working memory increases volume in the basal ganglia.

建立神经生理学和工作记忆功能模型的一种方法是前额叶皮质基底节工作记忆记忆模型。在这个模型中,脑前额叶外皮与基底神经节携手共同完成工作记忆的任务。许多研究已经证明了这一点。其中一个使用消融技术治疗癫痫发作、脑前额叶外皮和基底神经节受损的患者。对因服用甲基苯丙胺而导致大脑改变的病人进行的额外研究发现,训练工作记忆增加了基底神经节的容量。

Effects of stress on neurophysiology

Working memory is impaired by acute and chronic psychological stress. This phenomenon was first discovered in animal studies by Arnsten and colleagues,[106] who have shown that stress-induced catecholamine release in PFC rapidly decreases PFC neuronal firing and impairs working memory performance through feedforward, intracellular signaling pathways.[107] Exposure to chronic stress leads to more profound working memory deficits and additional architectural changes in PFC, including dendritic atrophy and spine loss,[108] which can be prevented by inhibition of protein kinase C signaling.[109] fMRI research has extended this research to humans, and confirms that reduced working memory caused by acute stress links to reduced activation of the PFC, and stress increased levels of catecholamines.[110] Imaging studies of medical students undergoing stressful exams have also shown weakened PFC functional connectivity, consistent with the animal studies.[111] The marked effects of stress on PFC structure and function may help to explain how stress can cause or exacerbate mental illness.

Working memory is impaired by acute and chronic psychological stress. This phenomenon was first discovered in animal studies by Arnsten and colleagues, who have shown that stress-induced catecholamine release in PFC rapidly decreases PFC neuronal firing and impairs working memory performance through feedforward, intracellular signaling pathways. Exposure to chronic stress leads to more profound working memory deficits and additional architectural changes in PFC, including dendritic atrophy and spine loss, which can be prevented by inhibition of protein kinase C signaling. fMRI research has extended this research to humans, and confirms that reduced working memory caused by acute stress links to reduced activation of the PFC, and stress increased levels of catecholamines. Imaging studies of medical students undergoing stressful exams have also shown weakened PFC functional connectivity, consistent with the animal studies. The marked effects of stress on PFC structure and function may help to explain how stress can cause or exacerbate mental illness.

工作记忆受到急性和慢性心理压力的损害。这种现象最早是由 Arnsten 和他的同事们在动物实验中发现的,他们发现应激诱导 PFC 中儿茶酚胺的释放可以迅速降低 PFC 神经元的放电,并通过前馈和细胞内信号通路损害工作记忆。长期暴露在压力下会导致更深层次的工作记忆缺陷和额外的 PFC 结构变化,包括树突萎缩和脊柱丧失,这些都可以通过抑制蛋白激酶C 信号来预防。功能磁共振成像的研究已经将这项研究扩展到人类,并证实急性压力导致的工作记忆减少与 PFC 的激活减少有关,而压力增加了儿茶酚胺的水平。医学院学生在经历紧张的考试后的成像研究也表明 PFC 功能连接性减弱,这与动物实验结果一致。压力对 PFC 结构和功能的显著影响可能有助于解释压力如何导致或加重精神疾病。

The more stress in one's life, the lower the efficiency of working memory in performing simple cognitive tasks. Students who performed exercises that reduced the intrusion of negative thoughts showed an increase in their working memory capacity. Mood states (positive or negative) can have an influence on the neurotransmitter dopamine, which in turn can affect problem solving.[112]

The more stress in one's life, the lower the efficiency of working memory in performing simple cognitive tasks. Students who performed exercises that reduced the intrusion of negative thoughts showed an increase in their working memory capacity. Mood states (positive or negative) can have an influence on the neurotransmitter dopamine, which in turn can affect problem solving.

生活中压力越大,工作记忆在完成简单认知任务时的效率就越低。那些进行减少负面思想入侵的练习的学生,他们的工作记忆容量有所增加。情绪状态(积极或消极)会影响神经递质多巴胺,从而影响问题解决。

Effects of alcohol on neurophysiology

Alcohol abuse can result in brain damage which impairs working memory.[113] Alcohol has an effect on the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) response. The BOLD response correlates increased blood oxygenation with brain activity, which makes this response a useful tool for measuring neuronal activity.[114] The BOLD response affects regions of the brain such as the basal ganglia and thalamus when performing a working memory task. Adolescents who start drinking at a young age show a decreased BOLD response in these brain regions.[115] Alcohol dependent young women in particular exhibit less of a BOLD response in parietal and frontal cortices when performing a spatial working memory task.[116] Binge drinking, specifically, can also affect one's performance on working memory tasks, particularly visual working memory.[117][118] Additionally, there seems to be a gender difference in regards to how alcohol affects working memory. While women perform better on verbal working memory tasks after consuming alcohol compared to men, they appear to perform worse on spatial working memory tasks as indicated by less brain activity.[119][120] Finally, age seems to be an additional factor. Older adults are more susceptible than others to the effects of alcohol on working memory.[121]

Alcohol abuse can result in brain damage which impairs working memory. Alcohol has an effect on the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) response. The BOLD response correlates increased blood oxygenation with brain activity, which makes this response a useful tool for measuring neuronal activity. The BOLD response affects regions of the brain such as the basal ganglia and thalamus when performing a working memory task. Adolescents who start drinking at a young age show a decreased BOLD response in these brain regions. Alcohol dependent young women in particular exhibit less of a BOLD response in parietal and frontal cortices when performing a spatial working memory task. Binge drinking, specifically, can also affect one's performance on working memory tasks, particularly visual working memory. Additionally, there seems to be a gender difference in regards to how alcohol affects working memory. While women perform better on verbal working memory tasks after consuming alcohol compared to men, they appear to perform worse on spatial working memory tasks as indicated by less brain activity. Finally, age seems to be an additional factor. Older adults are more susceptible than others to the effects of alcohol on working memory.

酗酒会导致大脑损伤,从而损害工作记忆。酒精对血氧水平依赖性(BOLD)反应有影响。BOLD 反应将增加的血氧含量与大脑活动联系起来,这使得这种反应成为测量神经元活动的有用工具。在执行工作记忆任务时,BOLD 反应影响大脑的基底神经节和丘脑等区域。从小就开始喝酒的青少年大脑区域的 BOLD 反应降低。特别是酒精依赖的年轻女性在执行空间工作记忆任务时,顶叶和额叶皮层的大胆反应较少。酗酒,特别是,也可以影响一个人的工作记忆任务的表现,特别是视觉工作记忆。此外,在酒精如何影响工作记忆方面,似乎也存在性别差异。与男性相比,女性在饮酒后的非文字工作记忆任务中表现得更好,但她们在空间工作记忆任务中的表现似乎更差,这表现在她们的大脑活动更少。最后,年龄似乎是一个额外的因素。老年人比其他人更容易受到酒精对工作记忆的影响。

Genetics

Behavioral genetics

Individual differences in working-memory capacity are to some extent heritable; that is, about half of the variation between individuals is related to differences in their genes.[122][123][124] The genetic component of variability of working-memory capacity is largely shared with that of fluid intelligence.[123][122]