玻尔兹曼方程

此词条由栗子CUGB翻译整理。

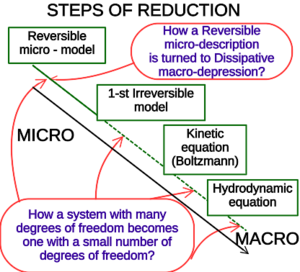

The Boltzmann equation or Boltzmann transport equation (BTE) describes the statistical behaviour of a thermodynamic system not in a state of equilibrium, devised by Ludwig Boltzmann in 1872.[2] The classic example of such a system is a fluid with temperature gradients in space causing heat to flow from hotter regions to colder ones, by the random but biased transport of the particles making up that fluid. In the modern literature the term Boltzmann equation is often used in a more general sense, referring to any kinetic equation that describes the change of a macroscopic quantity in a thermodynamic system, such as energy, charge or particle number.

玻尔兹曼方程或玻尔兹曼输运方程(Boltzmann transport equation, BTE)是一个描述非热力学平衡状态的热力学系统统计行为的偏微分方程,由路德维希·玻尔兹曼 Ludwig Boltzmann于1872年提出。[2] 这类系统的经典实例是:在空间中具有温度梯度的流体,组成该流体的粒子通过随机但具有偏向性的传输使得热量从较热的区域流向较冷的区域。在现代文献中,玻尔兹曼方程一词通常用于更一般的意义上,指的是描述热力学系统中宏观量变化的任何动力学方程,如能量、电荷或粒子数。

The equation arises not by analyzing the individual positions and momenta of each particle in the fluid but rather by considering a probability distribution for the position and momentum of a typical particle—that is, the probability that the particle occupies a given very small region of space (mathematically the volume element [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3 \bf{r} }[/math]) centered at the position [math]\displaystyle{ \bf{r} }[/math], and has momentum nearly equal to a given momentum vector [math]\displaystyle{ \bf{p} }[/math] (thus occupying a very small region of momentum space [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3 \bf{p} }[/math]), at an instant of time.

玻尔兹曼方程并不分析流体中每个粒子的单个位置和动量,而是只考虑一类粒子的位置和动量的概率分布,此类粒子某一时刻在几何空间占据以给定位置[math]\displaystyle{ \bf{r} }[/math]为中心的小邻域(数学上的体积元[math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3 \bf{r} }[/math]),且其动量几乎与给定动量矢量[math]\displaystyle{ \bf{p} }[/math]相等,在动量空间占据非常小的区域[math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3 \bf{p} }[/math]。

The Boltzmann equation can be used to determine how physical quantities change, such as heat energy and momentum, when a fluid is in transport. One may also derive other properties characteristic to fluids such as viscosity, thermal conductivity, and electrical conductivity (by treating the charge carriers in a material as a gas).[2] See also convection–diffusion equation.

玻尔兹曼方程可以用来确定流体在运输过程中物理量如何变化,比如热能和动量。人们还可以推导出流体的其他特性,如粘度、热导率和电导率(通过将材料中的载流子当作气体来处理)。[2] 参见对流扩散方程。

The equation is a nonlinear integro-differential equation, and the unknown function in the equation is a probability density function in six-dimensional space of a particle position and momentum. The problem of existence and uniqueness of solutions is still not fully resolved, but some recent results are quite promising.[3][4]

玻尔兹曼方程是非线性积分微分方程,方程中的未知函数是位置和动量在六维空间中的概率密度函数。方程解的存在唯一性仍然是未完全解决的问题,但是一些研究显示解决这一问题是很有希望的。[3][4]

Overview 概述

The phase space and density function 相空间和密度函数

The set of all possible positions r and momenta p is called the phase space of the system; in other words a set of three coordinates for each position coordinate x, y, z, and three more for each momentum component px, py, pz. The entire space is 6-dimensional: a point in this space is (r, p) = (x, y, z, px, py, pz), and each coordinate is parameterized by time t. The small volume ("differential volume element") is written

系统中所有可能的位置r和动量p的集合称为系统的相空间,集合中位置坐标记为 x,y,z,动量坐标记为px,py,pz。整个空间是6维的:空间中一点可以表示为(r, p) = ( x, y, z, px, py, pz ),每个坐标由时间 t 参数化。微元(即微分体积元)写作:

[math]\displaystyle{ \text{d}^3\mathbf{r}\,\text{d}^3\mathbf{p} = \text{d}x\,\text{d}y\,\text{d}z\,\text{d}p_x\,\text{d}p_y\,\text{d}p_z. }[/math].

Since the probability of N molecules which all have r and p within [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3\bf{r} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3\bf{p} }[/math] is in question, at the heart of the equation is a quantity f which gives this probability per unit phase-space volume, or probability per unit length cubed per unit momentum cubed, at an instant of time t. This is a probability density function: f (r, p, t), defined so that,

[math]\displaystyle{ \text{d}N = f (\mathbf{r},\mathbf{p},t)\,\text{d}^3\mathbf{r}\,\text{d}^3\mathbf{p} }[/math]

由于在[math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3\bf{r} }[/math][math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3\bf{p} }[/math]的N个分子都具有的概率都位置r和动量p存在疑问,玻尔兹曼方程的核心是f,它可以给出在某一时刻t单位相空间体积的概率。定义概率密度函数: f (r,p,t) 得到,

[math]\displaystyle{ \text{d}N = f (\mathbf{r},\mathbf{p},t)\,\text{d}^3\mathbf{r}\,\text{d}^3\mathbf{p} }[/math]

is the number of molecules which all have positions lying within a volume element [math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{r} }[/math] about r and momenta lying within a momentum space element [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3\bf{p} }[/math] about p, at time t[5]. Integrating over a region of position space and momentum space gives the total number of particles which have positions and momenta in that region:

dN是在t时刻,关于(r,p)的微体积元[math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{r} }[/math]和微动量元[math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d}^3\bf{p} }[/math]内的分子数目。在位置空间和动量空间的一个区域上积分,得出在该区域中具有位置和动量的粒子总数:

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} N &=\underset{momenta}\int\text{d}^{3}\mathbf{p}\underset{positions}\int\text{d}^{3}\mathbf{r}f(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{p},t)\\[5pt] &=\underset{momenta}\iiint\; \; \; \underset{positions}\iiint f(x,y,z,p_{x},p_{y},p_{z},t)\; \text{d}x\,\text{d}y\,\text{d}z\,\text{d}p_x\,\text{d}p_y\,\text{d}p_z \end{align} }[/math]

which is a 6-fold integral. While f is associated with a number of particles, the phase space is for one-particle (not all of them, which is usually the case with deterministic many-body systems), since only one r and p is in question. It is not part of the analysis to use r1, p1 for particle 1, r2, p2 for particle 2, etc. up to rN, pN for particle N.

虽然f与一群粒子有关,但相空间是针对单一粒子进行讨论(对于所有粒子的分析通常是确定性多体系统的情况),因为只有一个r和p是需要考虑的。使用r1, p1代表粒子1,r2, p2代表粒子2,......,直到rN, pN代表粒子N,都不在考虑范围之内。

It is assumed the particles in the system are identical (so each has an identical mass m). For a mixture of more than one chemical species, one distribution is needed for each, see below.

系统假设粒子都是相同的(因此每个粒子的质量m相同)。对于组成多于一种化学物质的混合物,其中每种物质都需要一种分布,见下文。

一般形式

The general equation can then be written as[6]

玻尔兹曼方程的一般形式可以写作:

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{df}{dt} = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial t}\right)_\text{force} + \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial t}\right)_\text{diff} + \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial t}\right)_\text{coll}, }[/math]

其中“force”一词指外界对粒子施加的力(而不是粒子间的作用),“diff”表示粒子扩散,“coll”表示粒子碰撞,指碰撞中粒子间相互的作用力。上述三项的具体形式将会在下文给出[7]。注意,一些作者会使用 v 表示粒子的速度,而不是动量 p。这两个物理量可以通过动量的定义p = mv联系起来。

where the "force" term corresponds to the forces exerted on the particles by an external influence (not by the particles themselves), the "diff" term represents the diffusion of particles, and "coll" is the collision term – accounting for the forces acting between particles in collisions. Expressions for each term on the right side are provided below[7].

Note that some authors use the particle velocity v instead of momentum p; they are related in the definition of momentum by p = mv.

The force and diffusion terms “force”项与“diff”项

Consider particles described by [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] , each experiencing an external force [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math] not due to other particles (see the collision term for the latter treatment).

Suppose at time [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] some number of particles all have position [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] within element [math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{r} }[/math] and momentum [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] within [math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{p} }[/math]. If a force [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math] instantly acts on each particle, then at time [math]\displaystyle{ t+\Delta t }[/math] their position will be [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r}+\Delta \mathbf{r}= \textbf{r}+\frac{\textbf{p}}{m}\Delta t }[/math] and momentum [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p}+\Delta \mathbf{p}= \mathbf{p}+\mathbf{F}\Delta t }[/math]. Then, in the absence of collisions, [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] must satisfy

[math]\displaystyle{ f\left ( \textbf{r}+\frac{\textbf{p}}{m}\Delta t,\textbf{p}+\textbf{F}\Delta t,t+\Delta t \right )\, d^{3}\textbf{r}\, d^{3}\textbf{p}= f(\textbf{r},\textbf{p},t)\, d^{3}\textbf{r}\, d^{3}\textbf{p} }[/math]

Note that we have used the fact that the phase space volume element [math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{r} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{p} }[/math] is constant, which can be shown using Hamilton's equations (see the discussion under Liouville's theorem). However, since collisions do occur, the particle density in the phase-space volume [math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{r} }[/math] '[math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{p} }[/math] changes, so

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} dN_{coll} &= \left ( \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} \right )_{coll}\Delta td^{3}\textbf{r}\, d^{3}\textbf{p}\\[5pt] & = f\left ( \textbf{r}+\frac{\textbf{p}}{m}\Delta t,\textbf{p}+\textbf{F}\Delta t,t+\Delta t \right )\, d^{3}\textbf{r}\, d^{3}\textbf{p}- f(\textbf{r},\textbf{p},t)\, d^{3}\textbf{r}\, d^{3}\textbf{p}\\[5pt] & =\Delta f d^{3}\textbf{r}\, d^{3}\textbf{p} \end{align} }[/math]

(1)

where Δf is the total change in f. Dividing (1) by [math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{r} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ d^3\bf{p} }[/math] Δt and taking the limits Δt → 0 and Δf → 0, we have

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d f}{d t} = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial t} \right)_\mathrm{coll} }[/math]

(2)

The total differential of f is:

-

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} d f & = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} \, dt +\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \, dx +\frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \, dy +\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} \, dz \right) +\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial p_x} \, dp_x +\frac{\partial f}{\partial p_y} \, dp_y +\frac{\partial f}{\partial p_z} \, dp_z \right)\\[5pt] & = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t}dt +\nabla f \cdot d\mathbf{r} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{p}}\cdot d\mathbf{p} \\[5pt] & = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t}dt +\nabla f \cdot \frac{\mathbf{p}}{m}dt + \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{p}}\cdot \mathbf{F} \, dt \end{align} }[/math]

(3)

where ∇ is the gradient operator, · is the dot product,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{p}} = \mathbf{\hat{e}}_x\frac{\partial f}{\partial p_x} + \mathbf{\hat{e}}_y\frac{\partial f}{\partial p_y} + \mathbf{\hat{e}}_z \frac{\partial f}{\partial p_z}= \nabla_\mathbf{p}f }[/math]

is a shorthand for the momentum analogue of ∇, and êx, êy, êz are Cartesian unit vectors.

Final statement

Dividing (3) by dt and substituting into (2) gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} + \frac{\mathbf{p}}{m}\cdot\nabla f + \mathbf{F} \cdot \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{p}} = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial t} \right)_\mathrm{coll} }[/math]

In this context, F(r, t) is the force field acting on the particles in the fluid, and m is the mass of the particles. The term on the right hand side is added to describe the effect of collisions between particles; if it is zero then the particles do not collide. The collisionless Boltzmann equation, where individual collisions are replaced with long-range aggregated interactions, e.g. Coulomb interactions, is often called the Vlasov equation.

This equation is more useful than the principal one above, yet still incomplete, since f cannot be solved unless the collision term in f is known. This term cannot be found as easily or generally as the others – it is a statistical term representing the particle collisions, and requires knowledge of the statistics the particles obey, like the Maxwell–Boltzmann, Fermi–Dirac or Bose–Einstein distributions.

The collision term (Stosszahlansatz) and molecular chaos

Two-body collision term

A key insight applied by Boltzmann was to determine the collision term resulting solely from two-body collisions between particles that are assumed to be uncorrelated prior to the collision. This assumption was referred to by Boltzmann as the "Stosszahlansatz " and is also known as the "molecular chaos assumption". Under this assumption the collision term can be written as a momentum-space integral over the product of one-particle distribution functions:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial t}\right)_\text{coll} = \iint gI(g, \Omega)[f(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{p'}_A, t) f(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{p'}_B,t) - f(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{p}_A,t) f(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{p}_B,t)] \,d\Omega \,d^3\mathbf{p}_A \,d^3\mathbf{p}_B, }[/math]

where pA and pB are the momenta of any two particles (labeled as A and B for convenience) before a collision, p′A and p′B are the momenta after the collision,

- [math]\displaystyle{ g = |\mathbf{p}_B - \mathbf{p}_A| = |\mathbf{p'}_B - \mathbf{p'}_A| }[/math]

is the magnitude of the relative momenta (see relative velocity for more on this concept), and I(g, Ω) is the differential cross section of the collision, in which the relative momenta of the colliding particles turns through an angle θ into the element of the solid angle dΩ, due to the collision.

Simplifications to the collision term

Since much of the challenge in solving the Boltzmann equation originates with the complex collision term, attempts have been made to "model" and simplify the collision term. The best known model equation is due to Bhatnagar, Gross and Krook.[8] The assumption in the BGK approximation is that the effect of molecular collisions is to force a non-equilibrium distribution function at a point in physical space back to a Maxwellian equilibrium distribution function and that the rate at which this occurs is proportional to the molecular collision frequency. The Boltzmann equation is therefore modified to the BGK form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} + \frac{\mathbf{p}}{m}\cdot\nabla f + \mathbf{F} \cdot \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{p}} = \nu (f_0 - f), }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \nu }[/math] is the molecular collision frequency, and [math]\displaystyle{ f_0 }[/math] is the local Maxwellian distribution function given the gas temperature at this point in space.

通用方程(对于混合物)

For a mixture of chemical species labelled by indices i = 1, 2, 3, ..., n the equation for species i is[9]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial f_i}{\partial t} + \frac{\mathbf{p}_i}{m_i} \cdot \nabla f_i + \mathbf{F} \cdot \frac{\partial f_i}{\partial \mathbf{p}_i} = \left(\frac{\partial f_i}{\partial t} \right)_\text{coll}, }[/math]

where fi = fi(r, pi, t), and the collision term is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(\frac{\partial f_i}{\partial t} \right)_{\mathrm{coll}} = \sum_{j=1}^n \iint g_{ij} I_{ij}(g_{ij}, \Omega)[f'_i f'_j - f_if_j] \,d\Omega\,d^3\mathbf{p'}, }[/math]

where f′ = f′(p′i, t), the magnitude of the relative momenta is

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_{ij} = |\mathbf{p}_i - \mathbf{p}_j| = |\mathbf{p'}_i - \mathbf{p'}_j|, }[/math]

and Iij is the differential cross-section, as before, between particles i and j. The integration is over the momentum components in the integrand (which are labelled i and j). The sum of integrals describes the entry and exit of particles of species i in or out of the phase-space element.

应用与推广

Conservation equations

The Boltzmann equation can be used to derive the fluid dynamic conservation laws for mass, charge, momentum, and energy.[10]:p 163 For a fluid consisting of only one kind of particle, the number density n is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ n = \int f \,d^3p. }[/math]

The average value of any function A is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \langle A \rangle = \frac 1 n \int A f \,d^3p. }[/math]

Since the conservation equations involve tensors, the Einstein summation convention will be used where repeated indices in a product indicate summation over those indices. Thus [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{x} \mapsto x_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p} \mapsto p_i = m w_i }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ w_i }[/math] is the particle velocity vector. Define [math]\displaystyle{ A(p_i) }[/math] as some function of momentum [math]\displaystyle{ p_i }[/math] only, which is conserved in a collision. Assume also that the force [math]\displaystyle{ F_i }[/math] is a function of position only, and that f is zero for [math]\displaystyle{ p_i \to \pm\infty }[/math]. Multiplying the Boltzmann equation by A and integrating over momentum yields four terms, which, using integration by parts, can be expressed as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \int A \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} \,d^3p = \frac{\partial }{\partial t} (n \langle A \rangle), }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \int \frac{p_j A}{m}\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_j} \,d^3p = \frac{1}{m}\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}(n\langle A p_j \rangle), }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \int A F_j \frac{\partial f}{\partial p_j} \,d^3p = -nF_j\left\langle \frac{\partial A}{\partial p_j}\right\rangle, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \int A \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial t}\right)_\text{coll} \,d^3p = 0, }[/math]

where the last term is zero, since A is conserved in a collision. Letting [math]\displaystyle{ A = m }[/math], the mass of the particle, the integrated Boltzmann equation becomes the conservation of mass equation:[10]:pp 12,168

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\rho + \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}(\rho V_j) = 0, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \rho = mn }[/math] is the mass density, and [math]\displaystyle{ V_i = \langle w_i\rangle }[/math] is the average fluid velocity.

Letting [math]\displaystyle{ A = p_i }[/math], the momentum of the particle, the integrated Boltzmann equation becomes the conservation of momentum equation:[10]:pp 15,169

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial}{\partial t}(\rho V_i) + \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}(\rho V_i V_j+P_{ij}) - nF_i = 0, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ P_{ij} = \rho \langle (w_i-V_i) (w_j-V_j) \rangle }[/math] is the pressure tensor (the viscous stress tensor plus the hydrostatic pressure).

Letting [math]\displaystyle{ A =\frac{p_i p_i}{2m} }[/math], the kinetic energy of the particle, the integrated Boltzmann equation becomes the conservation of energy equation:[10]:pp 19,169

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial}{\partial t}(u + \tfrac{1}{2}\rho V_i V_i) + \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} (uV_j + \tfrac{1}{2}\rho V_i V_i V_j + J_{qj} + P_{ij}V_i) - nF_iV_i = 0, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ u = \tfrac{1}{2} \rho \langle (w_i-V_i) (w_i-V_i) \rangle }[/math] is the kinetic thermal energy density, and [math]\displaystyle{ J_{qi} = \tfrac{1}{2} \rho \langle(w_i - V_i)(w_k - V_k)(w_k - V_k)\rangle }[/math] is the heat flux vector.

Hamiltonian mechanics

In Hamiltonian mechanics, the Boltzmann equation is often written more generally as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\mathbf{L}}[f]=\mathbf{C}[f], \, }[/math]

where L is the Liouville operator (there is an inconsistent definition between the Liouville operator as defined here and the one in the article linked) describing the evolution of a phase space volume and C is the collision operator. The non-relativistic form of L is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\mathbf{L}}_\mathrm{NR} = \frac{\partial}{\partial t} + \frac{\mathbf{p}}{m} \cdot \nabla + \mathbf{F}\cdot\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{p}}\,. }[/math]

Quantum theory and violation of particle number conservation

It is possible to write down relativistic quantum Boltzmann equations for relativistic quantum systems in which the number of particles is not conserved in collisions. This has several applications in physical cosmology,[11] including the formation of the light elements in Big Bang nucleosynthesis, the production of dark matter and baryogenesis. It is not a priori clear that the state of a quantum system can be characterized by a classical phase space density f. However, for a wide class of applications a well-defined generalization of f exists which is the solution of an effective Boltzmann equation that can be derived from first principles of quantum field theory.[12]

General relativity and astronomy

The Boltzmann equation is of use in galactic dynamics. A galaxy, under certain assumptions, may be approximated as a continuous fluid; its mass distribution is then represented by f; in galaxies, physical collisions between the stars are very rare, and the effect of gravitational collisions can be neglected for times far longer than the age of the universe.

Its generalization in general relativity.[13] is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\mathbf{L}}_\mathrm{GR}=p^\alpha\frac{\partial}{\partial x^\alpha} - \Gamma^\alpha{}_{\beta\gamma}p^\beta p^\gamma\frac{\partial}{\partial p^\alpha}, }[/math]

where Γαβγ is the Christoffel symbol of the second kind (this assumes there are no external forces, so that particles move along geodesics in the absence of collisions), with the important subtlety that the density is a function in mixed contravariant-covariant (xi, pi) phase space as opposed to fully contravariant (xi, pi) phase space.[14][15]

In physical cosmology the fully covariant approach has been used to study the cosmic microwave background radiation.[16] More generically the study of processes in the early universe often attempt to take into account the effects of quantum mechanics and general relativity.[11] In the very dense medium formed by the primordial plasma after the Big Bang, particles are continuously created and annihilated. In such an environment quantum coherence and the spatial extension of the wavefunction can affect the dynamics, making it questionable whether the classical phase space distribution f that appears in the Boltzmann equation is suitable to describe the system. In many cases it is, however, possible to derive an effective Boltzmann equation for a generalized distribution function from first principles of quantum field theory.[12] This includes the formation of the light elements in Big Bang nucleosynthesis, the production of dark matter and baryogenesis.

方程求解

Exact solutions to the Boltzmann equations have been proven to exist in some cases;[17] this analytical approach provides insight, but is not generally usable in practical problems.

这种分析方法提供了洞察力,但在实际问题中通常不能使用。

Instead, numerical methods (including finite elements and lattice Boltzmann methods) are generally used to find approximate solutions to the various forms of the Boltzmann equation. Example applications range from hypersonic aerodynamics in rarefied gas flows[18][19] to plasma flows.[20] An application of the Boltzmann equation in electrodynamics is the calculation of the electrical conductivity - the result is in leading order identical with the semiclassical result.[21]

相反,数值方法(包括有限元)通常用于寻找各种形式的玻尔兹曼方程的近似解。示例应用范围从稀薄气流中的高超音速空气动力学到等离子流。

Close to local equilibrium, solution of the Boltzmann equation can be represented by an asymptotic expansion in powers of Knudsen number (the Chapman-Enskog expansion[22]). The first two terms of this expansion give the Euler equations and the Navier-Stokes equations. The higher terms have singularities. The problem of developing mathematically the limiting processes, which lead from the atomistic view (represented by Boltzmann's equation) to the laws of motion of continua, is an important part of Hilbert's sixth problem.[23]

在接近局部均衡的情况下,玻尔兹曼方程的解可以用一个克努森数的渐近展开表示(Chapman-Enskog 展开式)。这个展开式的前两项给出了欧拉方程和纳维-斯托克斯方程。较高的项有奇点。从原子观点(以玻尔兹曼方程为代表)到连续统运动定律的极限过程的数学发展问题,是希尔伯特第六个问题的重要组成部分。

另见

注释

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gorban, Alexander N.; Karlin, Ilya V. (2005). Invariant Manifolds for Physical and Chemical Kinetics. Lecture Notes in Physics (LNP, vol. 660). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/b98103. ISBN 978-3-540-22684-0. https://www.academia.edu/17378865. Alt URL

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), R. G. Lerner, G. L. Trigg, VHC publishers, 1991, ISBN (Verlagsgesellschaft) 3-527-26954-1, ISBN (VHC Inc.) 0-89573-752-3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 DiPerna, R. J.; Lions, P.-L. (1989). "On the Cauchy problem for Boltzmann equations: global existence and weak stability". Ann. of Math. 2. 130 (2): 321–366. doi:10.2307/1971423. JSTOR 1971423.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Philip T. Gressman & Robert M. Strain (2010). "Global classical solutions of the Boltzmann equation with long-range interactions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (13): 5744–5749. arXiv:1002.3639. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5744G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001185107. PMC 2851887. PMID 20231489.

- ↑ Huang, Kerson (1987). Statistical Mechanics (Second ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-471-81518-1.

- ↑ McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), C. B. Parker, 1994, .

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), C. B. Parker, 1994, ISBN 0-07-051400-3.

- ↑ Bhatnagar, P. L.; Gross, E. P.; Krook, M. (1954-05-01). "A Model for Collision Processes in Gases. I. Small Amplitude Processes in Charged and Neutral One-Component Systems". Physical Review. 94 (3): 511–525. Bibcode:1954PhRv...94..511B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.94.511.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), R. G. Lerner, G. L. Trigg, VHC publishers, 1991, ISBN (Verlagsgesellschaft) 3-527-26954-1, ISBN (VHC Inc.) 0-89573-752-3.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 de Groot, S. R.; Mazur, P. (1984). Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics. New York: Dover Publications Inc.. ISBN 978-0-486-64741-8.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Edward Kolb; Michael Turner (1990). The Early Universe. Westview Press. ISBN 9780201626742.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 M. Drewes; C. Weniger; S. Mendizabal (8 January 2013). "The Boltzmann equation from quantum field theory". Phys. Lett. B. 718 (3): 1119–1124. arXiv:1202.1301. Bibcode:2013PhLB..718.1119D. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.11.046. S2CID 119253828.

- ↑ Ehlers J (1971) General Relativity and Cosmology (Varenna), R K Sachs (Academic Press NY);Thorne K S (1980) Rev. Mod. Phys., 52, 299; Ellis G F R, Treciokas R, Matravers D R, (1983) Ann. Phys., 150, 487}

- ↑ Debbasch, Fabrice; Willem van Leeuwen (2009). "General relativistic Boltzmann equation I: Covariant treatment". Physica A. 388 (7): 1079–1104. Bibcode:2009PhyA..388.1079D. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2008.12.023.

- ↑ Debbasch, Fabrice; Willem van Leeuwen (2009). "General relativistic Boltzmann equation II: Manifestly covariant treatment". Physica A. 388 (9): 1818–34. Bibcode:2009PhyA..388.1818D. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2009.01.009.

- ↑ Maartens R, Gebbie T, Ellis GFR (1999). "Cosmic microwave background anisotropies: Nonlinear dynamics". Phys. Rev. D. 59 (8): 083506

- ↑ Philip T. Gressman, Robert M. Strain (2011). "Global Classical Solutions of the Boltzmann Equation without Angular Cut-off". Journal of the American Mathematical Society. 24 (3): 771. arXiv:1011.5441. doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-2011-00697-8. S2CID 115167686.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Evans, Ben; Morgan, Ken; Hassan, Oubay (2011-03-01). "A discontinuous finite element solution of the Boltzmann kinetic equation in collisionless and BGK forms for macroscopic gas flows". Applied Mathematical Modelling. 35 (3): 996–1015. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2010.07.027.

- ↑ Evans, B.; Walton, S.P. (December 2017). "Aerodynamic optimisation of a hypersonic reentry vehicle based on solution of the Boltzmann–BGK equation and evolutionary optimisation". Applied Mathematical Modelling. 52: 215–240. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2017.07.024. ISSN 0307-904X.

- ↑ Pareschi, L.; Russo, G. (2000-01-01). "Numerical Solution of the Boltzmann Equation I: Spectrally Accurate Approximation of the Collision Operator". SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis. 37 (4): 1217–1245. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.46.2853. doi:10.1137/S0036142998343300. ISSN 0036-1429.

- ↑ H.J.W. Müller-Kirsten, Basics of Statistical Mechanics, Chapter 13, 2nd ed., World Scientific (2013), .

- ↑ Sydney Chapman; Thomas George Cowling The mathematical theory of non-uniform gases: an account of the kinetic theory of viscosity, thermal conduction, and diffusion in gases, Cambridge University Press, 1970.

- ↑ "Theme issue 'Hilbert's sixth problem'". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 376 (2118). 2018. doi:10.1098/rsta/376/2118.

参考文献

- Harris, Stewart (1971). An introduction to the theory of the Boltzmann equation. Dover Books. pp. 221. ISBN 978-0-486-43831-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=KfYK1lyq3VYC.. Very inexpensive introduction to the modern framework (starting from a formal deduction from Liouville and the Bogoliubov–Born–Green–Kirkwood–Yvon hierarchy (BBGKY) in which the Boltzmann equation is placed). Most statistical mechanics textbooks like Huang still treat the topic using Boltzmann's original arguments. To derive the equation, these books use a heuristic explanation that does not bring out the range of validity and the characteristic assumptions that distinguish Boltzmann's from other transport equations like Fokker–Planck or Landau equations.

- Arkeryd, Leif (1972). "On the Boltzmann equation part I: Existence". Arch. Rational Mech. Anal. 45 (1): 1–16. Bibcode:1972ArRMA..45....1A. doi:10.1007/BF00253392. S2CID 117877311.

- Arkeryd, Leif (1972). "On the Boltzmann equation part II: The full initial value problem". Arch. Rational Mech. Anal. 45 (1): 17–34. Bibcode:1972ArRMA..45...17A. doi:10.1007/BF00253393. S2CID 119481100.

- Arkeryd, Leif (1972). "On the Boltzmann equation part I: Existence". Arch. Rational Mech. Anal. 45 (1): 1–16. Bibcode:1972ArRMA..45....1A. doi:10.1007/BF00253392. S2CID 117877311.

- DiPerna, R. J.; Lions, P.-L. (1989). "On the Cauchy problem for Boltzmann equations: global existence and weak stability". Ann. of Math. 2. 130 (2): 321–366. doi:10.2307/1971423. JSTOR 1971423.