此词条暂由小竹凉翻译,翻译字数共4526,未经人工整理和审校,带来阅读不便,请见谅。

An artificial cell, synthetic cell or minimal cell is an engineered particle that mimics one or many functions of a biological cell. Often, artificial cells are biological or polymeric membranes which enclose biologically active materials.[1] As such, liposomes, polymersomes, nanoparticles, microcapsules and a number of other particles can qualify as artificial cells.

An artificial cell, synthetic cell or minimal cell is an engineered particle that mimics one or many functions of a biological cell. Often, artificial cells are biological or polymeric membranes which enclose biologically active materials. As such, liposomes, polymersomes, nanoparticles, microcapsules and a number of other particles can qualify as artificial cells.

人工细胞、人工合成细胞或最小细胞是一种模仿生物细胞单个或多个功能的工程粒子。通常,人工细胞是包裹生物活性物质的生物膜或聚合物膜。因此,脂质体、聚合物泡囊、纳米微粒、微胶囊和其他一些颗粒可以被定性为人工细胞。 ここまで!!!!!

The terms "artificial cell" and "synthetic cell" are used in a variety of different fields and can have different meanings, as it is also reflected in the different sections of this article. Some stricter definitions are based on the assumption that the term "cell" directly relates to biological cells and that these structures therefore have to be alive (or part of a living organism) and, further, that the term "artificial" implies that these structures are artificially built from the bottom-up, i.e. from basic components. As such, in the area of synthetic biology, an artificial cell can be understood as a completely synthetically made cell that can capture energy, maintain ion gradients, contain macromolecules as well as store information and have the ability to replicate.[2] This kind of artificial cell has not yet been made.

The terms "artificial cell" and "synthetic cell" are used in a variety of different fields and can have different meanings, as it is also reflected in the different sections of this article. Some stricter definitions are based on the assumption that the term "cell" directly relates to biological cells and that these structures therefore have to be alive (or part of a living organism) and, further, that the term "artificial" implies that these structures are artificially built from the bottom-up, i.e. from basic components. As such, in the area of synthetic biology, an artificial cell can be understood as a completely synthetically made cell that can capture energy, maintain ion gradients, contain macromolecules as well as store information and have the ability to replicate. This kind of artificial cell has not yet been made.

”人造细胞”和”合成细胞”这两个术语用于各种不同的领域,可能有不同的含义,因为它们也反映在本文的不同章节中。一些更严格的定义是基于这样的假设,即”细胞”一词直接与生物细胞有关,因此这些结构必须是活的(或活的有机体的一部分) ,而且”人工”一词意味着这些结构是从下往上人工建造的,即。从基本组成部分。因此,在合成生物学领域,人造细胞可以被理解为一个完全合成的细胞,可以捕获能量,维持离子梯度,包含大分子,以及存储信息,并具有复制能力。这种人造细胞还没有制造出来。

However, in other cases, the term "artificial" does not imply that the entire structure is man-made, but instead, it can refer to the idea that certain functions or structures of biological cells can be replaced or supplemented with a synthetic entity.

However, in other cases, the term "artificial" does not imply that the entire structure is man-made, but instead, it can refer to the idea that certain functions or structures of biological cells can be replaced or supplemented with a synthetic entity.

然而,在其他情况下,”人造”一词并不意味着整个结构是人造的,而是指生物细胞的某些功能或结构可以用合成实体取代或补充的想法。

In other fields, the term "artificial cell" can refer to any compartment that somewhat resembles a biological cell in size or structure, which is synthetically made, or even fully made from non-biological components. The term "artificial cell" is also used for structures with direct applications such as compartments for drug delivery. Micro-encapsulation allows for metabolism within the membrane, exchange of small molecules and prevention of passage of large substances across it.[3][4] The main advantages of encapsulation include improved mimicry in the body, increased solubility of the cargo and decreased immune responses. Notably, artificial cells have been clinically successful in hemoperfusion.[5]

In other fields, the term "artificial cell" can refer to any compartment that somewhat resembles a biological cell in size or structure, which is synthetically made, or even fully made from non-biological components. The term "artificial cell" is also used for structures with direct applications such as compartments for drug delivery. Micro-encapsulation allows for metabolism within the membrane, exchange of small molecules and prevention of passage of large substances across it. The main advantages of encapsulation include improved mimicry in the body, increased solubility of the cargo and decreased immune responses. Notably, artificial cells have been clinically successful in hemoperfusion.

在其他领域,”人造细胞”一词可指在尺寸或结构上有点象生物细胞的任何隔间,这种隔间是由非生物成分合成的,甚至是完全由非生物成分制成的。术语“人工细胞”也用于具有直接应用的结构,例如用于药物传递的隔室。微囊化可以促进细胞膜内的新陈代谢,交换小分子,防止大型物质通过细胞膜。包囊的主要优点包括改善体内的拟态,增加货物的溶解性和减少免疫反应。值得注意的是,人工细胞在临床上已成功应用于血液灌流。

Bottom-up engineering of living artificial cells

The German pathologist Rudolf Virchow brought forward the idea that not only does life arise from cells, but every cell comes from another cell; "Omnis cellula e cellula".[6] Until now, most attempts to create an artificial cell have only created a package that can mimic certain tasks of the cell. Advances in cell-free transcription and translation reactions allow the expression of many genes, but these efforts are far from producing a fully operational cell.

The German pathologist Rudolf Virchow brought forward the idea that not only does life arise from cells, but every cell comes from another cell; "Omnis cellula e cellula". Until now, most attempts to create an artificial cell have only created a package that can mimic certain tasks of the cell. Advances in cell-free transcription and translation reactions allow the expression of many genes, but these efforts are far from producing a fully operational cell.

德国病理学家鲁道夫 · 韦尔乔夫提出了这样一个观点: 生命不仅来自细胞,而且每一个细胞都来自另一个细胞。到目前为止,大多数创建人工细胞的尝试都只创建了能够模仿细胞特定任务的包。在无细胞转录和翻译反应的进步允许许多基因的表达,但这些努力远远没有产生一个完全运作的细胞。

A bottom-up approach to build an artificial cell would involve creating a protocell de novo, entirely from non-living materials. As the term "cell" implies, one prerequisite is the generation of some sort of compartment that defines an individual, cellular unit. Phospholipid membranes are an obvious choice as compartmentalizing boundaries,[7] as they act as selective barriers in all living biological cells. Scientists can encapsulate biomolecules in cell-sized phospholipid vesicles and by doing so, observe these molecules to act similarly as in biological cells and thereby recreate certain cell functions.[8] In a similar way, functional biological building blocks can be encapsulated in these lipid compartments to achieve the synthesis of (however rudimentary) artificial cells.

A bottom-up approach to build an artificial cell would involve creating a protocell de novo, entirely from non-living materials. As the term "cell" implies, one prerequisite is the generation of some sort of compartment that defines an individual, cellular unit. Phospholipid membranes are an obvious choice as compartmentalizing boundaries, as they act as selective barriers in all living biological cells. Scientists can encapsulate biomolecules in cell-sized phospholipid vesicles and by doing so, observe these molecules to act similarly as in biological cells and thereby recreate certain cell functions. In a similar way, functional biological building blocks can be encapsulated in these lipid compartments to achieve the synthesis of (however rudimentary) artificial cells.

自下而上构建人造细胞的方法包括完全用非生物材料创造原始细胞。正如术语“细胞”所暗示的那样,一个先决条件是生成某种定义单个细胞单元的隔间。磷脂膜是一个明显的选择作为划分界限,因为他们作为选择性屏障在所有活的生物细胞。科学家可以将生物分子包裹在细胞大小的磷脂小泡中,通过这种方法,观察这些分子在生物细胞中的作用类似,从而重建某些细胞功能。类似地,功能性生物构建块可以被封装在这些脂室中,以实现人工细胞的合成(无论多么初级)。

It is proposed to create a phospholipid bilayer vesicle with DNA capable of self-reproducing using synthetic genetic information. The three primary elements of such artificial cells are the formation of a lipid membrane, DNA and RNA replication through a template process and the harvesting of chemical energy for active transport across the membrane.[9][10] The main hurdles foreseen and encountered with this proposed protocell are the creation of a minimal synthetic DNA that holds all sufficient information for life, and the reproduction of non-genetic components that are integral in cell development such as molecular self-organization.[11] However, it is hoped that this kind of bottom-up approach would provide insight into the fundamental questions of organizations at the cellular level and the origins of biological life. So far, no completely artificial cell capable of self-reproduction has been synthesized using the molecules of life, and this objective is still in a distant future although various groups are currently working towards this goal.[12]

It is proposed to create a phospholipid bilayer vesicle with DNA capable of self-reproducing using synthetic genetic information. The three primary elements of such artificial cells are the formation of a lipid membrane, DNA and RNA replication through a template process and the harvesting of chemical energy for active transport across the membrane. The main hurdles foreseen and encountered with this proposed protocell are the creation of a minimal synthetic DNA that holds all sufficient information for life, and the reproduction of non-genetic components that are integral in cell development such as molecular self-organization. However, it is hoped that this kind of bottom-up approach would provide insight into the fundamental questions of organizations at the cellular level and the origins of biological life. So far, no completely artificial cell capable of self-reproduction has been synthesized using the molecules of life, and this objective is still in a distant future although various groups are currently working towards this goal.

提出利用合成的遗传信息创造具有 DNA 自我繁殖能力的磷脂双分子层囊泡。这种人造细胞的三个主要成分是脂膜的形成、通过模板过程进行的 DNA 和 RNA 复制以及化学能量的收集,以便在脂膜上进行主动运输。预见和遇到的主要障碍与这个拟议的原始细胞是创造一个最小的合成 DNA,其中包含所有足够的生命信息,以及非遗传成分的复制是细胞发展中不可或缺的,如分子自我组织。但是,希望这种自下而上的方法能够深入了解组织在细胞层面的基本问题和生物生命的起源。迄今为止,还没有利用生命分子合成出能够自我繁殖的完全人造细胞,尽管目前各种团体正朝着这一目标努力,但这一目标仍然是遥远的未来。

Another method proposed to create a protocell more closely resembles the conditions believed to have been present during evolution known as the primordial soup. Various RNA polymers could be encapsulated in vesicles and in such small boundary conditions, chemical reactions would be tested for.[13]

Another method proposed to create a protocell more closely resembles the conditions believed to have been present during evolution known as the primordial soup. Various RNA polymers could be encapsulated in vesicles and in such small boundary conditions, chemical reactions would be tested for.

另一种创造原始细胞的方法更接近于被认为存在于被称为原始汤的进化过程中的条件。各种 RNA 聚合物可以被囊泡包裹,在这样小的边界条件下,化学反应将被测试。

Ethics and controversy

Protocell research has created controversy and opposing opinions, including critics of the vague definition of "artificial life".[14] The creation of a basic unit of life is the most pressing ethical concern, although the most widespread worry about protocells is their potential threat to human health and the environment through uncontrolled replication.[15]

Protocell research has created controversy and opposing opinions, including critics of the vague definition of "artificial life". The creation of a basic unit of life is the most pressing ethical concern, although the most widespread worry about protocells is their potential threat to human health and the environment through uncontrolled replication.

原细胞研究引起了争议和反对意见,包括对”人工生命”的模糊定义的批评。创造一个基本的生命单位是最紧迫的伦理问题,尽管最普遍的担忧是原始细胞通过不受控制的复制对人类健康和环境的潜在威胁。

International Research Community

In the mid-2010s the research community started recognising the need to unify the field of synthetic cell research, acknowledging that the task of constructing an entire living organism from non-living components was beyond the resources of a single country.[16]

In the mid-2010s the research community started recognising the need to unify the field of synthetic cell research, acknowledging that the task of constructing an entire living organism from non-living components was beyond the resources of a single country.

2010年代中期,研究界开始认识到有必要统一合成细胞研究领域,承认用非生物成分构建整个活体的任务超出了一个国家的资源范围。

In 2017 the international Build-a-Cell large-scale research collaboration for the construction of synthetic living cell was started,[17] followed by national synthetic cell organizations in several countries. Those national organizations include FabriCell,[18] MaxSynBio[19] and BaSyC.[20] The European synthetic cell efforts were unified in 2019 as SynCellEU initiative.[21]

In 2017 the international Build-a-Cell large-scale research collaboration for the construction of synthetic living cell was started, followed by national synthetic cell organizations in several countries. Those national organizations include FabriCell, MaxSynBio and BaSyC. The European synthetic cell efforts were unified in 2019 as SynCellEU initiative.

2017年开始了国际合成活细胞建造大规模研究合作,以建造合成活细胞,随后在若干国家开展了国家合成细胞组织。这些全国性组织包括 FabriCell、 MaxSynBio 和 BaSyC。欧洲合成细胞的努力在2019年被统一为 SynCellEU 倡议。

Top-down approach to create a minimal living cell

Members from the J. Craig Venter Institute have used a top-down computational approach to knock out genes in a living organism to a minimum set of genes.[22] In 2010, the team succeeded in creating a replicating strain of Mycoplasma mycoides (Mycoplasma laboratorium) using synthetically created DNA deemed to be the minimum requirement for life which was inserted into a genomically empty bacterium.[22] It is hoped that the process of top-down biosynthesis will enable the insertion of new genes that would perform profitable functions such as generation of hydrogen for fuel or capturing excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.[15] The myriad regulatory, metabolic, and signaling networks are not completely characterized. These top-down approaches have limitations for the understanding of fundamental molecular regulation, since the host organisms have a complex and incompletely defined molecular composition.[23] In 2019 a complete computational model of all pathways in Mycoplasma Syn3.0 cell was published, representing the first complete in silico model for a living minimal organism.[24]

Members from the J. Craig Venter Institute have used a top-down computational approach to knock out genes in a living organism to a minimum set of genes. In 2010, the team succeeded in creating a replicating strain of Mycoplasma mycoides (Mycoplasma laboratorium) using synthetically created DNA deemed to be the minimum requirement for life which was inserted into a genomically empty bacterium. It is hoped that the process of top-down biosynthesis will enable the insertion of new genes that would perform profitable functions such as generation of hydrogen for fuel or capturing excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The myriad regulatory, metabolic, and signaling networks are not completely characterized. These top-down approaches have limitations for the understanding of fundamental molecular regulation, since the host organisms have a complex and incompletely defined molecular composition. In 2019 a complete computational model of all pathways in Mycoplasma Syn3.0 cell was published, representing the first complete in silico model for a living minimal organism.

= = 自上而下的方法创造最小的活细胞 = = 来自克莱格·凡特研究所的成员使用自上而下的计算方法将活有机体中的基因敲除到最小的一组基因。2010年,研究小组利用人工合成的被认为是生命最低要求的 DNA,成功地创造了一个复制品系的丝状支原体(辛西娅) ,这种 DNA 被插入到一个基因组上空的细菌中。人们希望,自上而下的生物合成过程将能够插入新的基因,这些基因将发挥有利的作用,例如产生氢气作为燃料或在大气中捕获过量的二氧化碳。无数的调节、新陈代谢和信号网络并不是完全的特征。这些自上而下的方法对于理解基本的分子调控有局限性,因为宿主生物有一个复杂的和不完全确定的分子组成。2019年,支原体 Syn3.0细胞中所有通路的完整计算模型被发表,这是第一个完整的微生物活体硅胶模型。

Heavy investing in biology has been done by large companies such as ExxonMobil, who has partnered with Synthetic Genomics Inc; Craig Venter's own biosynthetics company in the development of fuel from algae.[25]

Heavy investing in biology has been done by large companies such as ExxonMobil, who has partnered with Synthetic Genomics Inc; Craig Venter's own biosynthetics company in the development of fuel from algae.

大量的生物投资已经被大公司完成,比如埃克森美孚公司,它与合成基因公司合作; Craig Venter 自己的生物合成公司,开发藻类燃料。

As of 2016, Mycoplasma genitalium is the only organism used as a starting point for engineering a minimal cell, since it has the smallest known genome that can be cultivated under laboratory conditions; the wild-type variety has 482, and removing exactly 100 genes deemed non-essential resulted in a viable strain with improved growth rates. Reduced-genome Escherichia coli is considered more useful, and viable strains have been developed with 15% of the genome removed.[26]:29–30

As of 2016, Mycoplasma genitalium is the only organism used as a starting point for engineering a minimal cell, since it has the smallest known genome that can be cultivated under laboratory conditions; the wild-type variety has 482, and removing exactly 100 genes deemed non-essential resulted in a viable strain with improved growth rates. Reduced-genome Escherichia coli is considered more useful, and viable strains have been developed with 15% of the genome removed.

截至2016年,生殖支原体是唯一一种用作基因工程最小细胞起始点的生物,因为它拥有可以在实验室条件下培育的已知最小的基因组; 野生型品种有482个基因,去除正好100个被认为非必需的基因,就能培育出生长速度提高的可存活菌株。减少基因组大肠桿菌被认为更有用,而且已经开发出可生存的菌株,去除了15% 的基因组。

A variation of an artificial cell has been created in which a completely synthetic genome was introduced to genomically emptied host cells.[22] Although not completely artificial because the cytoplasmic components as well as the membrane from the host cell are kept, the engineered cell is under control of a synthetic genome and is able to replicate.

A variation of an artificial cell has been created in which a completely synthetic genome was introduced to genomically emptied host cells. Although not completely artificial because the cytoplasmic components as well as the membrane from the host cell are kept, the engineered cell is under control of a synthetic genome and is able to replicate.

一种人造细胞的变异已经被创造出来,其中一个完全合成的基因组被引入到基因清空的宿主细胞中。虽然由于宿主细胞的细胞质成分和细胞膜被保留下来而不完全是人工合成的,但是工程细胞受控于人工合成的基因组,能够复制。

Artificial cells for medical applications

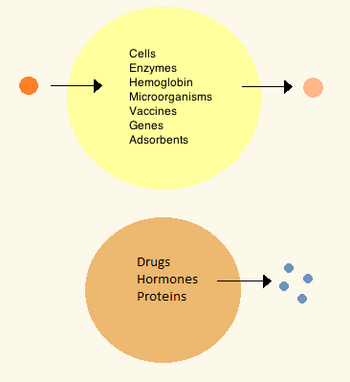

thumb|350px|alt=Two types of artificial cells, one with contents meant to stay inside, the other for drug delivery and diffusing contents. |Standard artificial cell (top) and drug delivery artificial cell (bottom).

= = 医用人造细胞 = = 拇指 | 350px | alt = 两种类型的人造细胞,一种内含物意味着留在体内,另一种用于药物输送和扩散。| 标准人工细胞(上)和药物传递人工细胞(下)。

History

In the 1960s Thomas Chang developed microcapsules which he would later call "artificial cells", as they were cell-sized compartments made from artificial materials.[27] These cells consisted of ultrathin membranes of nylon, collodion or crosslinked protein whose semipermeable properties allowed diffusion of small molecules in and out of the cell. These cells were micron-sized and contained cells, enzymes, hemoglobin, magnetic materials, adsorbents and proteins.[3]

In the 1960s Thomas Chang developed microcapsules which he would later call "artificial cells", as they were cell-sized compartments made from artificial materials. These cells consisted of ultrathin membranes of nylon, collodion or crosslinked protein whose semipermeable properties allowed diffusion of small molecules in and out of the cell. These cells were micron-sized and contained cells, enzymes, hemoglobin, magnetic materials, adsorbents and proteins.

= = 历史 = = 20世纪60年代,托马斯 · 张研制出了微囊,后来他称之为“人造细胞”,因为它们是由人造材料制成的细胞大小的隔间。这些细胞由尼龙、火棉胶或交联蛋白质的超薄膜组成,其半透性特性使得小分子可以扩散进出细胞。这些细胞是微米大小,含有细胞,酶,血红蛋白,磁性材料,吸附剂和蛋白质。

Later artificial cells have ranged from hundred-micrometer to nanometer dimensions and can carry microorganisms, vaccines, genes, drugs, hormones and peptides.[3] The first clinical use of artificial cells was in hemoperfusion by the encapsulation of activated charcoal.[28]

Later artificial cells have ranged from hundred-micrometer to nanometer dimensions and can carry microorganisms, vaccines, genes, drugs, hormones and peptides. The first clinical use of artificial cells was in hemoperfusion by the encapsulation of activated charcoal.

后来人造细胞的尺寸从百微米到纳米不等,可以携带微生物、疫苗、基因、药物、激素和多肽。人工细胞的第一次临床应用是以药用活性炭为包囊进行血液灌流。

In the 1970s, researchers were able to introduce enzymes, proteins and hormones to biodegradable microcapsules, later leading to clinical use in diseases such as Lesch–Nyhan syndrome.[29] Although Chang's initial research focused on artificial red blood cells, only in the mid-1990s were biodegradable artificial red blood cells developed.[30] Artificial cells in biological cell encapsulation were first used in the clinic in 1994 for treatment in a diabetic patient[31] and since then other types of cells such as hepatocytes, adult stem cells and genetically engineered cells have been encapsulated and are under study for use in tissue regeneration.[32][33]

In the 1970s, researchers were able to introduce enzymes, proteins and hormones to biodegradable microcapsules, later leading to clinical use in diseases such as Lesch–Nyhan syndrome. Although Chang's initial research focused on artificial red blood cells, only in the mid-1990s were biodegradable artificial red blood cells developed. Artificial cells in biological cell encapsulation were first used in the clinic in 1994 for treatment in a diabetic patient and since then other types of cells such as hepatocytes, adult stem cells and genetically engineered cells have been encapsulated and are under study for use in tissue regeneration.

在20世纪70年代,研究人员能够将酶、蛋白质和激素引入到可生物降解的微胶囊中,后来这种微胶囊在诸如莱希-尼亨氏症候群之类的疾病中得到临床应用。尽管 Chang 最初的研究集中在人造红细胞上,但直到20世纪90年代中期,才出现了可生物降解的人造红细胞。1994年,生物细胞封装的人工细胞首次在临床上用于治疗糖尿病患者,此后,其他类型的细胞,如肝细胞、成体干细胞和基因工程细胞已被封装,并正在研究用于组织再生。

Materials

Materials

= = 材料 =

thumb|450px|alt=Different types of artificial cell membranes. |Representative types of artificial cell membranes.

不同类型的人造细胞膜。| 有代表性的人造细胞膜。

Membranes for artificial cells can be made of simple polymers, crosslinked proteins, lipid membranes or polymer-lipid complexes. Further, membranes can be engineered to present surface proteins such as albumin, antigens, Na/K-ATPase carriers, or pores such as ion channels. Commonly used materials for the production of membranes include hydrogel polymers such as alginate, cellulose and thermoplastic polymers such as hydroxyethyl methacrylate-methyl methacrylate (HEMA- MMA), polyacrylonitrile-polyvinyl chloride (PAN-PVC), as well as variations of the above-mentioned.[4] The material used determines the permeability of the cell membrane, which for polymer depends on the molecular weight cut off (MWCO).[4] The MWCO is the maximum molecular weight of a molecule that may freely pass through the pores and is important in determining adequate diffusion of nutrients, waste and other critical molecules. Hydrophilic polymers have the potential to be biocompatible and can be fabricated into a variety of forms which include polymer micelles, sol-gel mixtures, physical blends and crosslinked particles and nanoparticles.[4] Of special interest are stimuli-responsive polymers that respond to pH or temperature changes for the use in targeted delivery. These polymers may be administered in the liquid form through a macroscopic injection and solidify or gel in situ because of the difference in pH or temperature. Nanoparticle and liposome preparations are also routinely used for material encapsulation and delivery. A major advantage of liposomes is their ability to fuse to cell and organelle membranes.

Membranes for artificial cells can be made of simple polymers, crosslinked proteins, lipid membranes or polymer-lipid complexes. Further, membranes can be engineered to present surface proteins such as albumin, antigens, Na/K-ATPase carriers, or pores such as ion channels. Commonly used materials for the production of membranes include hydrogel polymers such as alginate, cellulose and thermoplastic polymers such as hydroxyethyl methacrylate-methyl methacrylate (HEMA- MMA), polyacrylonitrile-polyvinyl chloride (PAN-PVC), as well as variations of the above-mentioned. The material used determines the permeability of the cell membrane, which for polymer depends on the molecular weight cut off (MWCO). The MWCO is the maximum molecular weight of a molecule that may freely pass through the pores and is important in determining adequate diffusion of nutrients, waste and other critical molecules. Hydrophilic polymers have the potential to be biocompatible and can be fabricated into a variety of forms which include polymer micelles, sol-gel mixtures, physical blends and crosslinked particles and nanoparticles. Of special interest are stimuli-responsive polymers that respond to pH or temperature changes for the use in targeted delivery. These polymers may be administered in the liquid form through a macroscopic injection and solidify or gel in situ because of the difference in pH or temperature. Nanoparticle and liposome preparations are also routinely used for material encapsulation and delivery. A major advantage of liposomes is their ability to fuse to cell and organelle membranes.

用于人造细胞的膜可以由简单的聚合物、交联蛋白质、脂质膜或聚合物-脂质复合物制成。此外,膜可以被设计成表面蛋白如白蛋白、抗原、 Na/k-atp 酶载体或孔隙如离子通道。常用的水凝胶聚合物如海藻酸钠、纤维素和热塑性聚合物如甲基丙烯酸羟乙酯-甲基丙烯酸甲酯(HEMA-MMA)、聚丙烯腈-聚氯乙烯(PAN-PVC) ,以及上述各种聚合物的变化。所用的材料决定了细胞膜的渗透性,对于聚合物来说,这取决于分子量截止(MWCO)。MWCO 是可以自由通过孔隙的分子的最大分子量,对于确定营养物质、废物和其他临界分子的充分扩散很重要。亲水性聚合物具有生物相容性的潜力,可以制成多种形式,包括聚合物胶束、溶胶-凝胶混合物、物理共混物以及交联粒子和纳米粒子。特别感兴趣的是刺激反应性聚合物,这种聚合物对 pH 值或温度变化作出反应,用于靶向传递。由于 pH 值和温度的不同,这些聚合物可以通过宏观注射和凝固或原位凝胶以液体形式给药。纳米颗粒和脂质体制剂也常用于材料的包封和递送。脂质体的一个主要优点是它们能够与细胞膜和细胞器膜融合。

Preparation

Many variations for artificial cell preparation and encapsulation have been developed. Typically, vesicles such as a nanoparticle, polymersome or liposome are synthesized. An emulsion is typically made through the use of high pressure equipment such as a high pressure homogenizer or a Microfluidizer. Two micro-encapsulation methods for nitrocellulose are also described below.

Many variations for artificial cell preparation and encapsulation have been developed. Typically, vesicles such as a nanoparticle, polymersome or liposome are synthesized. An emulsion is typically made through the use of high pressure equipment such as a high pressure homogenizer or a Microfluidizer. Two micro-encapsulation methods for nitrocellulose are also described below.

人工细胞的制备和包封已经发展出许多不同的方法。通常,囊泡,如纳米颗粒,聚合物或脂质体被合成。乳剂通常是通过使用高压设备,如高压均质器或微射流器制成的。硝化纤维素的两种微囊化方法也在下面描述。

High-pressure homogenization

In a high-pressure homogenizer, two liquids in oil/liquid suspension are forced through a small orifice under very high pressure. This process divides the products and allows the creation of extremely fine particles, as small as 1 nm.

In a high-pressure homogenizer, two liquids in oil/liquid suspension are forced through a small orifice under very high pressure. This process divides the products and allows the creation of extremely fine particles, as small as 1 nm.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =.这个过程分割的产品,并允许创造极其微小的颗粒,只有1纳米。

Microfluidization

This technique uses a patented Microfluidizer to obtain a greater amount of homogenous suspensions that can create smaller particles than homogenizers. A homogenizer is first used to create a coarse suspension which is then pumped into the microfluidizer under high pressure. The flow is then split into two streams which will react at very high velocities in an interaction chamber until desired particle size is obtained.[34] This technique allows for large scale production of phospholipid liposomes and subsequent material nanoencapsulations.

This technique uses a patented Microfluidizer to obtain a greater amount of homogenous suspensions that can create smaller particles than homogenizers. A homogenizer is first used to create a coarse suspension which is then pumped into the microfluidizer under high pressure. The flow is then split into two streams which will react at very high velocities in an interaction chamber until desired particle size is obtained. This technique allows for large scale production of phospholipid liposomes and subsequent material nanoencapsulations.

= = = = = 微射流技术使用专利的微射流器获得更多的均质悬浮液,可以产生比均质器更小的颗粒。均质器首先被用来制造粗颗粒悬浮液,然后在高压下被泵入微流体器。然后将流体分成两股流体,这两股流体将在相互作用室中以非常高的速度反应,直到得到所需的粒子尺寸。这种技术允许大规模生产磷脂脂质体和后续材料纳米包埋。

Drop method

In this method, a cell solution is incorporated dropwise into a collodion solution of cellulose nitrate. As the drop travels through the collodion, it is coated with a membrane thanks to the interfacial polymerization properties of the collodion. The cell later settles into paraffin where the membrane sets and is finally suspended a saline solution. The drop method is used for the creation of large artificial cells which encapsulate biological cells, stem cells and genetically engineered stem cells.

In this method, a cell solution is incorporated dropwise into a collodion solution of cellulose nitrate. As the drop travels through the collodion, it is coated with a membrane thanks to the interfacial polymerization properties of the collodion. The cell later settles into paraffin where the membrane sets and is finally suspended a saline solution. The drop method is used for the creation of large artificial cells which encapsulate biological cells, stem cells and genetically engineered stem cells.

在这种方法中,细胞溶液滴入硝酸纤维素的火棉胶溶液中。当液滴通过火棉胶时,由于火棉胶的界面聚合特性,它被涂上了一层膜。细胞随后沉积在石蜡中,细胞膜凝固,最后悬浮在盐溶液中。液滴法用于制造大型人造细胞,包裹生物细胞、干细胞和基因工程干细胞。

Emulsion method

The emulsion method differs in that the material to be encapsulated is usually smaller and is placed in the bottom of a reaction chamber where the collodion is added on top and centrifuged, or otherwise disturbed in order to create an emulsion. The encapsulated material is then dispersed and suspended in saline solution.

The emulsion method differs in that the material to be encapsulated is usually smaller and is placed in the bottom of a reaction chamber where the collodion is added on top and centrifuged, or otherwise disturbed in order to create an emulsion. The encapsulated material is then dispersed and suspended in saline solution.

乳化法的不同之处在于,要被包裹的材料通常较小,被放置在反应室的底部,在反应室的顶部加入火棉胶并离心,或以其他方式搅拌以便形成乳化液。然后将胶囊材料分散并悬浮在盐溶液中。

Clinical relevance

Clinical relevance

= = 临床相关性 =

Drug release and delivery

Artificial cells used for drug delivery differ from other artificial cells since their contents are intended to diffuse out of the membrane, or be engulfed and digested by a host target cell. Often used are submicron, lipid membrane artificial cells that may be referred to as nanocapsules, nanoparticles, polymersomes, or other variations of the term.

Artificial cells used for drug delivery differ from other artificial cells since their contents are intended to diffuse out of the membrane, or be engulfed and digested by a host target cell. Often used are submicron, lipid membrane artificial cells that may be referred to as nanocapsules, nanoparticles, polymersomes, or other variations of the term.

= = = = 药物的释放和运送 = = = = = = 用于药物运送的人造细胞与其他人造细胞不同,因为其内容物的目的是扩散出细胞膜,或者被宿主的靶细胞吞噬和消化。通常使用的是亚微米,脂膜人工细胞,可称为纳米胶囊,纳米粒子,聚合体,或其他任期的变种。

Enzyme therapy

Enzyme therapy is being actively studied for genetic metabolic diseases where an enzyme is over-expressed, under-expressed, defective, or not at all there. In the case of under-expression or expression of a defective enzyme, an active form of the enzyme is introduced in the body to compensate for the deficit. On the other hand, an enzymatic over-expression may be counteracted by introduction of a competing non-functional enzyme; that is, an enzyme which metabolizes the substrate into non-active products. When placed within an artificial cell, enzymes can carry out their function for a much longer period compared to free enzymes[3] and can be further optimized by polymer conjugation.[35]

Enzyme therapy is being actively studied for genetic metabolic diseases where an enzyme is over-expressed, under-expressed, defective, or not at all there. In the case of under-expression or expression of a defective enzyme, an active form of the enzyme is introduced in the body to compensate for the deficit. On the other hand, an enzymatic over-expression may be counteracted by introduction of a competing non-functional enzyme; that is, an enzyme which metabolizes the substrate into non-active products. When placed within an artificial cell, enzymes can carry out their function for a much longer period compared to free enzymes and can be further optimized by polymer conjugation.Park et al. 1981

目前正在积极研究酶疗法,用于治疗遗传代谢性疾病,其中一种酶过度表达、表达不足、有缺陷或根本不存在。在有缺陷的酶表达不足或表达不足的情况下,在体内引入一种活性形式的酶,以补偿缺陷。另一方面,酶的过度表达可以通过引入竞争性的非功能性酶来抵消,也就是说,一种酶将底物代谢为非活性产物。当置于人工细胞中时,酶可以比游离酶更长时间地发挥作用,并且可以通过聚合物接合进一步优化。帕克等。1981

The first enzyme studied under artificial cell encapsulation was asparaginase for the treatment of lymphosarcoma in mice. This treatment delayed the onset and growth of the tumor.[36] These initial findings led to further research in the use of artificial cells for enzyme delivery in tyrosine dependent melanomas.[37] These tumors have a higher dependency on tyrosine than normal cells for growth, and research has shown that lowering systemic levels of tyrosine in mice can inhibit growth of melanomas.[38] The use of artificial cells in the delivery of tyrosinase; and enzyme that digests tyrosine, allows for better enzyme stability and is shown effective in the removal of tyrosine without the severe side-effects associated with tyrosine depravation in the diet.[39]

The first enzyme studied under artificial cell encapsulation was asparaginase for the treatment of lymphosarcoma in mice. This treatment delayed the onset and growth of the tumor. These initial findings led to further research in the use of artificial cells for enzyme delivery in tyrosine dependent melanomas. These tumors have a higher dependency on tyrosine than normal cells for growth, and research has shown that lowering systemic levels of tyrosine in mice can inhibit growth of melanomas. The use of artificial cells in the delivery of tyrosinase; and enzyme that digests tyrosine, allows for better enzyme stability and is shown effective in the removal of tyrosine without the severe side-effects associated with tyrosine depravation in the diet.

人工细胞包埋法研究的第一种酶是治疗小鼠淋巴肉瘤的天冬酰胺酶。这种治疗延缓了肿瘤的发生和生长。这些初步的发现导致了在酪氨酸依赖性黑色素瘤中使用人工细胞进行酶传递的进一步研究。这些肿瘤的生长比正常细胞更依赖于酪氨酸,研究表明,降低小鼠全身酪氨酸水平可以抑制黑色素瘤的生长。利用人工细胞输送酪氨酸酶和消化酪氨酸的酶,可以提高酶的稳定性,并且能有效地去除酪氨酸,而不会产生与饮食中酪氨酸恶化有关的严重副作用。

Artificial cell enzyme therapy is also of interest for the activation of prodrugs such as ifosfamide in certain cancers. Artificial cells encapsulating the cytochrome p450 enzyme which converts this prodrug into the active drug can be tailored to accumulate in the pancreatic carcinoma or implanting the artificial cells close to the tumor site. Here, the local concentration of the activated ifosfamide will be much higher than in the rest of the body thus preventing systemic toxicity.[40] The treatment was successful in animals[41] and showed a doubling in median survivals amongst patients with advanced-stage pancreatic cancer in phase I/II clinical trials, and a tripling in one-year survival rate.[40]

Artificial cell enzyme therapy is also of interest for the activation of prodrugs such as ifosfamide in certain cancers. Artificial cells encapsulating the cytochrome p450 enzyme which converts this prodrug into the active drug can be tailored to accumulate in the pancreatic carcinoma or implanting the artificial cells close to the tumor site. Here, the local concentration of the activated ifosfamide will be much higher than in the rest of the body thus preventing systemic toxicity. The treatment was successful in animals and showed a doubling in median survivals amongst patients with advanced-stage pancreatic cancer in phase I/II clinical trials, and a tripling in one-year survival rate.

人工细胞酶疗法对于激活诸如异环磷酰胺之类的前药在某些癌症中也很有意义。将细胞色素 p450酶包裹在人工细胞中,将其转化为活性药物,可以特制地在胰腺癌中积累,或将人工细胞移植到肿瘤部位附近。在这里,被激活的异环磷酰胺的局部浓度将远远高于身体其他部位,从而防止全身中毒。这种治疗在动物身上取得了成功,在 i/II 期临床试验中,晚期胰腺癌患者的中位生存率增加了一倍,一年生存率增加了两倍。

Gene therapy

In treatment of genetic diseases, gene therapy aims to insert, alter or remove genes within an afflicted individual's cells. The technology relies heavily on viral vectors which raises concerns about insertional mutagenesis and systemic immune response that have led to human deaths[42][43] and development of leukemia[44][45] in clinical trials. Circumventing the need for vectors by using naked or plasmid DNA as its own delivery system also encounters problems such as low transduction efficiency and poor tissue targeting when given systemically.[4]

In treatment of genetic diseases, gene therapy aims to insert, alter or remove genes within an afflicted individual's cells. The technology relies heavily on viral vectors which raises concerns about insertional mutagenesis and systemic immune response that have led to human deaths and development of leukemia in clinical trials. Circumventing the need for vectors by using naked or plasmid DNA as its own delivery system also encounters problems such as low transduction efficiency and poor tissue targeting when given systemically.

在基因疾病的治疗中,基因疗法旨在插入、改变或移除受影响个体细胞内的基因。该技术严重依赖于病毒载体,这引起了对插入突变和系统免疫反应的关注,这些在临床试验中导致了人类死亡和白血病的发展。系统给药时,以裸质粒或质粒 DNA 作为自身的传递系统来规避载体的需要,也会遇到传递效率低、组织靶向性差等问题。

Artificial cells have been proposed as a non-viral vector by which genetically modified non-autologous cells are encapsulated and implanted to deliver recombinant proteins in vivo.[46] This type of immuno-isolation has been proven efficient in mice through delivery of artificial cells containing mouse growth hormone which rescued a growth-retardation in mutant mice.[47] A few strategies have advanced to human clinical trials for the treatment of pancreatic cancer, lateral sclerosis and pain control.[4]

Artificial cells have been proposed as a non-viral vector by which genetically modified non-autologous cells are encapsulated and implanted to deliver recombinant proteins in vivo. This type of immuno-isolation has been proven efficient in mice through delivery of artificial cells containing mouse growth hormone which rescued a growth-retardation in mutant mice. A few strategies have advanced to human clinical trials for the treatment of pancreatic cancer, lateral sclerosis and pain control.

人工细胞作为一种非病毒载体已被提出,通过基因修饰的非自体细胞被包裹和植入,在体内传递重组蛋白。这种类型的免疫隔离已被证明是有效的小鼠通过人工细胞含有小鼠生长激素,挽救生长阻滞的突变小鼠。一些治疗胰腺癌、脊髓侧索硬化症和疼痛控制的策略已经进入人体临床试验。

Hemoperfusion

The first clinical use of artificial cells was in hemoperfusion by the encapsulation of activated charcoal.[28] Activated charcoal has the capability of adsorbing many large molecules and has for a long time been known for its ability to remove toxic substances from the blood in accidental poisoning or overdose. However, perfusion through direct charcoal administration is toxic as it leads to embolisms and damage of blood cells followed by removal by platelets.[48] Artificial cells allow toxins to diffuse into the cell while keeping the dangerous cargo within their ultrathin membrane.[28]

The first clinical use of artificial cells was in hemoperfusion by the encapsulation of activated charcoal. Activated charcoal has the capability of adsorbing many large molecules and has for a long time been known for its ability to remove toxic substances from the blood in accidental poisoning or overdose. However, perfusion through direct charcoal administration is toxic as it leads to embolisms and damage of blood cells followed by removal by platelets. Artificial cells allow toxins to diffuse into the cell while keeping the dangerous cargo within their ultrathin membrane.

人工细胞的第一次临床应用是通过药用活性炭的包囊进行血液灌流。药用活性炭具有吸附许多大分子的能力,长期以来因其在意外中毒或过量服用中能够去除血液中的有毒物质而闻名。然而,通过直接使用木炭进行灌注是有毒的,因为它会导致血栓和血细胞损伤,随后血小板会被清除。人造细胞允许毒素扩散进入细胞,同时保持危险的货物在他们的超薄膜。

Artificial cell hemoperfusion has been proposed as a less costly and more efficient detoxifying option than hemodialysis,[3] in which blood filtering takes place only through size separation by a physical membrane. In hemoperfusion, thousands of adsorbent artificial cells are retained inside a small container through the use of two screens on either end through which patient blood perfuses. As the blood circulates, toxins or drugs diffuse into the cells and are retained by the absorbing material. The membranes of artificial cells are much thinner those used in dialysis and their small size means that they have a high membrane surface area. This means that a portion of cell can have a theoretical mass transfer that is a hundredfold higher than that of a whole artificial kidney machine.[3] The device has been established as a routine clinical method for patients treated for accidental or suicidal poisoning but has also been introduced as therapy in liver failure and kidney failure by carrying out part of the function of these organs.[3] Artificial cell hemoperfusion has also been proposed for use in immunoadsorption through which antibodies can be removed from the body by attaching an immunoadsorbing material such as albumin on the surface of the artificial cells. This principle has been used to remove blood group antibodies from plasma for bone marrow transplantation[49] and for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia through monoclonal antibodies to remove low-density lipoproteins.[50] Hemoperfusion is especially useful in countries with a weak hemodialysis manufacturing industry as the devices tend to be cheaper there and used in kidney failure patients.

Artificial cell hemoperfusion has been proposed as a less costly and more efficient detoxifying option than hemodialysis, in which blood filtering takes place only through size separation by a physical membrane. In hemoperfusion, thousands of adsorbent artificial cells are retained inside a small container through the use of two screens on either end through which patient blood perfuses. As the blood circulates, toxins or drugs diffuse into the cells and are retained by the absorbing material. The membranes of artificial cells are much thinner those used in dialysis and their small size means that they have a high membrane surface area. This means that a portion of cell can have a theoretical mass transfer that is a hundredfold higher than that of a whole artificial kidney machine. The device has been established as a routine clinical method for patients treated for accidental or suicidal poisoning but has also been introduced as therapy in liver failure and kidney failure by carrying out part of the function of these organs. Artificial cell hemoperfusion has also been proposed for use in immunoadsorption through which antibodies can be removed from the body by attaching an immunoadsorbing material such as albumin on the surface of the artificial cells. This principle has been used to remove blood group antibodies from plasma for bone marrow transplantation and for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia through monoclonal antibodies to remove low-density lipoproteins. Hemoperfusion is especially useful in countries with a weak hemodialysis manufacturing industry as the devices tend to be cheaper there and used in kidney failure patients.

与血液透析相比,人工细胞血液灌流被认为是一种成本更低、效率更高的解毒方法。在血液灌流中,成千上万的吸附性人造细胞通过使用病人血液灌流的两个屏幕被保留在一个小容器中。随着血液循环,毒素或药物扩散进入细胞,并被吸收材料所保留。人工细胞的细胞膜比透析用细胞的细胞膜要薄得多,细胞膜的小体积意味着细胞膜的表面积很大。这意味着一部分细胞理论上的质量传递比整个人工肾脏机器的质量传递高百倍。该装置已被确立为意外或自杀性中毒治疗患者的常规临床方法,但也被引入治疗肝功能衰竭和肾功能衰竭,实现这些器官的部分功能。人工细胞血液灌流也被提议用于免疫吸附,通过在人工细胞表面粘附免疫吸附材料,如白蛋白,可将抗体从体内除去。这一原理已被应用于从骨髓移植患者血浆中去除血型抗体,以及通过单克隆抗体去除低密度脂蛋白治疗高胆固醇血症。血液灌流在血液透析制造业薄弱的国家尤其有用,因为那里的血液透析设备往往更便宜,而且用于肾衰竭患者。

Encapsulated cells

Encapsulated cells

= = = 封装细胞 = = =

thumb|300px|alt=Schematic of cells encapsulated within an artificial membrane.|Schematic representation of encapsulated cells within artificial membrane.

细胞封装在人造膜内的示意图。

The most common method of preparation of artificial cells is through cell encapsulation. Encapsulated cells are typically achieved through the generation of controlled-size droplets from a liquid cell suspension which are then rapidly solidified or gelated to provide added stability. The stabilization may be achieved through a change in temperature or via material crosslinking.[4] The microenvironment that a cell sees changes upon encapsulation. It typically goes from being on a monolayer to a suspension in a polymer scaffold within a polymeric membrane. A drawback of the technique is that encapsulating a cell decreases its viability and ability to proliferate and differentiate.[51] Further, after some time within the microcapsule, cells form clusters that inhibit the exchange of oxygen and metabolic waste,[52] leading to apoptosis and necrosis thus limiting the efficacy of the cells and activating the host's immune system. Artificial cells have been successful for transplanting a number of cells including islets of Langerhans for diabetes treatment,[53] parathyroid cells and adrenal cortex cells.

The most common method of preparation of artificial cells is through cell encapsulation. Encapsulated cells are typically achieved through the generation of controlled-size droplets from a liquid cell suspension which are then rapidly solidified or gelated to provide added stability. The stabilization may be achieved through a change in temperature or via material crosslinking. The microenvironment that a cell sees changes upon encapsulation. It typically goes from being on a monolayer to a suspension in a polymer scaffold within a polymeric membrane. A drawback of the technique is that encapsulating a cell decreases its viability and ability to proliferate and differentiate. Further, after some time within the microcapsule, cells form clusters that inhibit the exchange of oxygen and metabolic waste, leading to apoptosis and necrosis thus limiting the efficacy of the cells and activating the host's immune system. Artificial cells have been successful for transplanting a number of cells including islets of Langerhans for diabetes treatment, parathyroid cells and adrenal cortex cells.

最常用的制备人造细胞的方法是通过细胞包囊。封装细胞通常是通过从液体细胞悬浮液中产生控制尺寸的液滴来实现的,然后快速凝固或凝胶化以提供额外的稳定性。稳定化可以通过温度的变化或材料的交联来实现。细胞在封装时看到的微环境变化。它通常从单分子层到悬浮在聚合物膜内的聚合物支架上。这种技术的缺点是封装细胞会降低其生存能力以及增殖和分化能力。此外,在微囊中待一段时间后,细胞会形成团簇,抑制氧气和代谢废物的交换,导致细胞凋亡和坏死,从而限制细胞的功效,激活宿主的免疫系统。人造细胞已经成功地移植了一些细胞,包括治疗糖尿病的胰岛、甲状旁腺细胞和肾上腺皮质细胞。

Encapsulated hepatocytes

Shortage of organ donors make artificial cells key players in alternative therapies for liver failure. The use of artificial cells for hepatocyte transplantation has demonstrated feasibility and efficacy in providing liver function in models of animal liver disease and bioartificial liver devices.[54] Research stemmed off experiments in which the hepatocytes were attached to the surface of a micro-carriers[55] and has evolved into hepatocytes which are encapsulated in a three-dimensional matrix in alginate microdroplets covered by an outer skin of polylysine. A key advantage to this delivery method is the circumvention of immunosuppression therapy for the duration of the treatment. Hepatocyte encapsulations have been proposed for use in a bioartifical liver. The device consists of a cylindrical chamber imbedded with isolated hepatocytes through which patient plasma is circulated extra-corporeally in a type of hemoperfusion. Because microcapsules have a high surface area to volume ratio, they provide large surface for substrate diffusion and can accommodate a large number of hepatocytes. Treatment to induced liver failure mice showed a significant increase in the rate of survival.[54] Artificial liver systems are still in early development but show potential for patients waiting for organ transplant or while a patient's own liver regenerates sufficiently to resume normal function. So far, clinical trials using artificial liver systems and hepatocyte transplantation in end-stage liver diseases have shown improvement of health markers but have not yet improved survival.[56] The short longevity and aggregation of artificial hepatocytes after transplantation are the main obstacles encountered. Hepatocytes co-encapsulated with stem cells show greater viability in culture and after implantation[57] and implantation of artificial stem cells alone have also shown liver regeneration.[58] As such interest has arisen in the use of stem cells for encapsulation in regenerative medicine.

Shortage of organ donors make artificial cells key players in alternative therapies for liver failure. The use of artificial cells for hepatocyte transplantation has demonstrated feasibility and efficacy in providing liver function in models of animal liver disease and bioartificial liver devices. Research stemmed off experiments in which the hepatocytes were attached to the surface of a micro-carriers and has evolved into hepatocytes which are encapsulated in a three-dimensional matrix in alginate microdroplets covered by an outer skin of polylysine. A key advantage to this delivery method is the circumvention of immunosuppression therapy for the duration of the treatment. Hepatocyte encapsulations have been proposed for use in a bioartifical liver. The device consists of a cylindrical chamber imbedded with isolated hepatocytes through which patient plasma is circulated extra-corporeally in a type of hemoperfusion. Because microcapsules have a high surface area to volume ratio, they provide large surface for substrate diffusion and can accommodate a large number of hepatocytes. Treatment to induced liver failure mice showed a significant increase in the rate of survival. Artificial liver systems are still in early development but show potential for patients waiting for organ transplant or while a patient's own liver regenerates sufficiently to resume normal function. So far, clinical trials using artificial liver systems and hepatocyte transplantation in end-stage liver diseases have shown improvement of health markers but have not yet improved survival. The short longevity and aggregation of artificial hepatocytes after transplantation are the main obstacles encountered. Hepatocytes co-encapsulated with stem cells show greater viability in culture and after implantation and implantation of artificial stem cells alone have also shown liver regeneration. As such interest has arisen in the use of stem cells for encapsulation in regenerative medicine.

器官捐献者的短缺使人造细胞成为治疗肝衰竭的替代疗法的关键。人工肝细胞用于肝细胞移植已被证实在动物肝病模型和生物人工肝装置中提供肝功能的可行性和有效性。实验中,肝细胞被附着在微载体表面,然后进化成肝细胞,包裹在由聚赖氨酸外皮覆盖的海藻酸钠微滴中的三维基质中。这种给药方法的一个关键优势是在治疗期间避免了免疫抑制治疗。肝细胞包囊已被提议用于生物人工肝。该装置由一个嵌有分离肝细胞的圆柱形腔室组成,病人的血浆通过这个腔室在一种血液灌流中循环。由于微囊具有很高的比表面积和体积比,它们为基质扩散提供了较大的表面积,并且可以容纳大量的肝细胞。对诱导性肝衰竭小鼠的治疗显示存活率显著提高。人工肝系统仍处于早期发展阶段,但对于等待器官移植或者病人自身的肝脏重新充分恢复正常功能的病人来说,显示出了潜力。迄今为止,使用人工肝系统和肝细胞移植治疗终末期肝病的临床试验已经显示健康指标的改善,但尚未提高存活率。移植后人工肝细胞的短寿命和聚集是目前肝移植面临的主要障碍。与干细胞共包裹的肝细胞在培养中表现出更大的生存能力,植入和植入人工干细胞后也表现出肝再生。因此,利用干细胞来包裹再生医学细胞的研究引起了人们的兴趣。

Encapsulated bacterial cells

The oral ingestion of live bacterial cell colonies has been proposed and is currently in therapy for the modulation of intestinal microflora,[59] prevention of diarrheal diseases,[60] treatment of H. Pylori infections, atopic inflammations,[61] lactose intolerance[62] and immune modulation,[63] amongst others. The proposed mechanism of action is not fully understood but is believed to have two main effects. The first is the nutritional effect, in which the bacteria compete with toxin producing bacteria. The second is the sanitary effect, which stimulates resistance to colonization and stimulates immune response.[4] The oral delivery of bacterial cultures is often a problem because they are targeted by the immune system and often destroyed when taken orally. Artificial cells help address these issues by providing mimicry into the body and selective or long term release thus increasing the viability of bacteria reaching the gastrointestinal system.[4] In addition, live bacterial cell encapsulation can be engineered to allow diffusion of small molecules including peptides into the body for therapeutic purposes.[4] Membranes that have proven successful for bacterial delivery include cellulose acetate and variants of alginate.[4] Additional uses that have arosen from encapsulation of bacterial cells include protection against challenge from M. Tuberculosis[64] and upregulation of Ig secreting cells from the immune system.[65] The technology is limited by the risk of systemic infections, adverse metabolic activities and the risk of gene transfer.[4] However, the greater challenge remains the delivery of sufficient viable bacteria to the site of interest.[4]

The oral ingestion of live bacterial cell colonies has been proposed and is currently in therapy for the modulation of intestinal microflora, prevention of diarrheal diseases, treatment of H. Pylori infections, atopic inflammations, lactose intolerance and immune modulation, amongst others. The proposed mechanism of action is not fully understood but is believed to have two main effects. The first is the nutritional effect, in which the bacteria compete with toxin producing bacteria. The second is the sanitary effect, which stimulates resistance to colonization and stimulates immune response. The oral delivery of bacterial cultures is often a problem because they are targeted by the immune system and often destroyed when taken orally. Artificial cells help address these issues by providing mimicry into the body and selective or long term release thus increasing the viability of bacteria reaching the gastrointestinal system. In addition, live bacterial cell encapsulation can be engineered to allow diffusion of small molecules including peptides into the body for therapeutic purposes. Membranes that have proven successful for bacterial delivery include cellulose acetate and variants of alginate. Additional uses that have arosen from encapsulation of bacterial cells include protection against challenge from M. Tuberculosis and upregulation of Ig secreting cells from the immune system. The technology is limited by the risk of systemic infections, adverse metabolic activities and the risk of gene transfer. However, the greater challenge remains the delivery of sufficient viable bacteria to the site of interest.

有人提出口服活菌落,目前正用于治疗肠道菌群的调节、预防腹泻疾病、治疗幽门螺杆菌感染、过敏性炎症、乳糖不耐症和免疫调节等。拟议的作用机制尚未得到充分理解,但被认为具有两个主要作用。首先是营养效应,即细菌与产毒细菌竞争。第二是卫生效应,刺激抵抗定殖和免疫反应。细菌培养物的口服给药通常是一个问题,因为它们是免疫系统的目标,通常在口服时被破坏。人工细胞通过向体内提供模仿和选择性或长期释放,从而提高进入胃肠道系统的细菌的生存能力,从而帮助解决这些问题。此外,可以设计活细菌包囊,使小分子(包括多肽)扩散到体内用于治疗目的。已被证明成功用于细菌传递的膜包括醋酸纤维素和海藻酸盐的变体。其他用途包括保护细菌细胞免受结核分枝杆菌的攻击和免疫系统分泌免疫球蛋白的增加。该技术受到系统性感染、不良代谢活动和基因转移风险的限制。然而,更大的挑战仍然是如何将足够多的有生命的细菌运送到感兴趣的部位。

Artificial blood cells as oxygen carriers

Nano sized oxygen carriers are used as a type of red blood cell substitutes, although they lack other components of red blood cells. They are composed of a synthetic polymersome or an artificial membrane surrounding purified animal, human or recombinant hemoglobin.[66] Overall, hemoglobin delivery continues to be a challenge because it is highly toxic when delivered without any modifications. In some clinical trials, vasopressor effects have been observed.[67][68]

Nano sized oxygen carriers are used as a type of red blood cell substitutes, although they lack other components of red blood cells. They are composed of a synthetic polymersome or an artificial membrane surrounding purified animal, human or recombinant hemoglobin.

Overall, hemoglobin delivery continues to be a challenge because it is highly toxic when delivered without any modifications. In some clinical trials, vasopressor effects have been observed.

人造血细胞作为氧载体被用作一种红细胞替代品,尽管它们缺乏红细胞的其他成分。它们由合成的聚合物或人工膜包裹在纯化的动物、人或重组的血红蛋白周围。总的来说,血红蛋白的输送仍然是一个挑战,因为它在没有任何修饰的情况下输送时是剧毒的。在一些临床试验中,已经观察到血管升压效应。

Artificial red blood cells

Research interest in the use of artificial cells for blood arose after the AIDS scare of the 1980s. Besides bypassing the potential for disease transmission, artificial red blood cells are desired because they eliminate drawbacks associated with allogenic blood transfusions such as blood typing, immune reactions and its short storage life of 42 days. A hemoglobin substitute may be stored at room temperature and not under refrigeration for more than a year.[3] Attempts have been made to develop a complete working red blood cell which comprises carbonic not only an oxygen carrier but also the enzymes associated with the cell. The first attempt was made in 1957 by replacing the red blood cell membrane by an ultrathin polymeric membrane[69] which was followed by encapsulation through a lipid membrane[70] and more recently a biodegradable polymeric membrane.[3] A biological red blood cell membrane including lipids and associated proteins can also be used to encapsulate nanoparticles and increase residence time in vivo by bypassing macrophage uptake and systemic clearance.[71]

Research interest in the use of artificial cells for blood arose after the AIDS scare of the 1980s. Besides bypassing the potential for disease transmission, artificial red blood cells are desired because they eliminate drawbacks associated with allogenic blood transfusions such as blood typing, immune reactions and its short storage life of 42 days. A hemoglobin substitute may be stored at room temperature and not under refrigeration for more than a year. Attempts have been made to develop a complete working red blood cell which comprises carbonic not only an oxygen carrier but also the enzymes associated with the cell. The first attempt was made in 1957 by replacing the red blood cell membrane by an ultrathin polymeric membrane which was followed by encapsulation through a lipid membrane and more recently a biodegradable polymeric membrane.

A biological red blood cell membrane including lipids and associated proteins can also be used to encapsulate nanoparticles and increase residence time in vivo by bypassing macrophage uptake and systemic clearance.

人造红细胞在1980年代的艾滋病恐慌之后,人们对使用人造红细胞制造血液产生了研究兴趣。除了避开疾病传播的可能性,人造红细胞也是人们所需要的,因为它们可以消除与同种异体输血相关的缺点,如血型鉴定、免疫反应及其短暂的42天储存期。血红蛋白替代物可以存放在室温下,而不是在冷藏条件下存放一年以上。人们已经尝试开发出一种完整工作的红细胞,它不仅包含碳酸,而且包含氧载体和与细胞相关的酶。第一次尝试是在1957年,用超薄聚合物膜代替红细胞膜,然后通过脂质膜和最近的可生物降解聚合物膜进行封装。包含脂质和相关蛋白质的生物红细胞膜还可以通过绕过巨噬细胞摄取和系统清除来包裹纳米颗粒和增加体内停留时间。

Artificial leuko-polymersomes

A leuko-polymersome is a polymersome engineered to have the adhesive properties of a leukocyte.[72] Polymersomes are vesicles composed of a bilayer sheet that can encapsulate many active molecules such as drugs or enzymes. By adding the adhesive properties of a leukocyte to their membranes, they can be made to slow down, or roll along epithelial walls within the quickly flowing circulatory system.

A leuko-polymersome is a polymersome engineered to have the adhesive properties of a leukocyte. Polymersomes are vesicles composed of a bilayer sheet that can encapsulate many active molecules such as drugs or enzymes. By adding the adhesive properties of a leukocyte to their membranes, they can be made to slow down, or roll along epithelial walls within the quickly flowing circulatory system.

= = = = = 人工白细胞聚合体是一种具有白细胞粘附特性的聚合体。聚合体是由双层薄片组成的囊泡,可以包裹许多活性分子,如药物或酶。通过将白细胞的粘附特性添加到细胞膜上,白细胞可以减慢速度,或者在快速流动的循环系统内沿着上皮细胞壁滚动。

Unconventional types of artificial cells

Electronic artificial cell

The concept of an Electronic Artificial Cell has been expanded in a series of 3 EU projects coordinated by John McCaskill from 2004 to 2015.

The concept of an Electronic Artificial Cell has been expanded in a series of 3 EU projects coordinated by John McCaskill from 2004 to 2015.

非常规类型的人造细胞电子人造细胞的概念在2004年至2015年由约翰 · 麦卡斯基尔协调的一系列欧盟项目中得到扩展。

The European Commission sponsored the development of the Programmable Artificial Cell Evolution (PACE) program[73] from 2004 to 2008 whose goal was to lay the foundation for the creation of "microscopic self-organizing, self-replicating, and evolvable autonomous entities built from simple organic and inorganic substances that can be genetically programmed to perform specific functions"[73] for the eventual integration into information systems. The PACE project developed the first Omega Machine, a microfluidic life support system for artificial cells that could complement chemically missing functionalities (as originally proposed by Norman Packard, Steen Rasmussen, Mark Beadau and John McCaskill). The ultimate aim was to attain an evolvable hybrid cell in a complex microscale programmable environment. The functions of the Omega Machine could then be removed stepwise, posing a series of solvable evolution challenges to the artificial cell chemistry. The project achieved chemical integration up to the level of pairs of the three core functions of artificial cells (a genetic subsystem, a containment system and a metabolic system), and generated novel spatially resolved programmable microfluidic environments for the integration of containment and genetic amplification.[73] The project led to the creation of the European center for living technology.[74]

The European Commission sponsored the development of the Programmable Artificial Cell Evolution (PACE) program from 2004 to 2008 whose goal was to lay the foundation for the creation of "microscopic self-organizing, self-replicating, and evolvable autonomous entities built from simple organic and inorganic substances that can be genetically programmed to perform specific functions" for the eventual integration into information systems. The PACE project developed the first Omega Machine, a microfluidic life support system for artificial cells that could complement chemically missing functionalities (as originally proposed by Norman Packard, Steen Rasmussen, Mark Beadau and John McCaskill). The ultimate aim was to attain an evolvable hybrid cell in a complex microscale programmable environment. The functions of the Omega Machine could then be removed stepwise, posing a series of solvable evolution challenges to the artificial cell chemistry. The project achieved chemical integration up to the level of pairs of the three core functions of artificial cells (a genetic subsystem, a containment system and a metabolic system), and generated novel spatially resolved programmable microfluidic environments for the integration of containment and genetic amplification. The project led to the creation of the European center for living technology.

2004年至2008年,欧洲联盟委员会赞助制定了可编程人造细胞进化方案,其目标是为最终融入信息系统奠定基础,创建”由简单的有机和无机物质构成的微观自组织、自我复制和可进化的自主实体,这些物质可通过遗传程序进行编程,以履行特定功能”。PACE 项目开发了第一台欧米茄机器,这是一种人工细胞的微流体生命支持系统,可以补充化学缺失的功能(最初由诺曼 · 帕卡德、斯蒂恩 · 拉斯穆森、马克 · 比多和约翰 · 麦卡斯基尔提出)。最终目标是在复杂的微型可编程环境中实现可进化的混合细胞。欧米茄机器的功能可以逐步删除,对人造细胞化学提出了一系列可解决的进化挑战。该项目实现了人工细胞三个核心功能(遗传子系统、包容系统和新陈代谢系统)成对的化学整合,并为包容和基因扩增的整合创造了新的空间分辨可编程微流体环境。这个项目导致了欧洲生物技术中心的建立。

Following this research, in 2007, John McCaskill proposed to concentrate on an electronically complemented artificial cell, called the Electronic Chemical Cell. The key idea was to use a massively parallel array of electrodes coupled to locally dedicated electronic circuitry, in a two-dimensional thin film, to complement emerging chemical cellular functionality. Local electronic information defining the electrode switching and sensing circuits could serve as an electronic genome, complementing the molecular sequential information in the emerging protocols. A research proposal was successful with the European Commission and an international team of scientists partially overlapping with the PACE consortium commenced work 2008-2012 on the project Electronic Chemical Cells. The project demonstrated among other things that electronically controlled local transport of specific sequences could be used as an artificial spatial control system for the genetic proliferation of future artificial cells, and that core processes of metabolism could be delivered by suitably coated electrode arrays.

Following this research, in 2007, John McCaskill proposed to concentrate on an electronically complemented artificial cell, called the Electronic Chemical Cell. The key idea was to use a massively parallel array of electrodes coupled to locally dedicated electronic circuitry, in a two-dimensional thin film, to complement emerging chemical cellular functionality. Local electronic information defining the electrode switching and sensing circuits could serve as an electronic genome, complementing the molecular sequential information in the emerging protocols. A research proposal was successful with the European Commission and an international team of scientists partially overlapping with the PACE consortium commenced work 2008-2012 on the project Electronic Chemical Cells. The project demonstrated among other things that electronically controlled local transport of specific sequences could be used as an artificial spatial control system for the genetic proliferation of future artificial cells, and that core processes of metabolism could be delivered by suitably coated electrode arrays.

在这项研究之后,2007年,约翰 · 麦卡斯基尔提议集中研究一种电子补充型人工电池,称为电子化学电池。关键的想法是在一个二维薄膜中,使用一个大规模并行处理机阵列的电极与局部专用电子电路耦合,以补充新出现的化学细胞功能。定义电极切换和传感电路的局部电子信息可以作为电子基因组,补充新协议中的分子序列信息。与欧洲联盟委员会的一项研究提案取得了成功,与计算机设备行动伙伴关系联盟部分重叠的一个国际科学家小组开始了2008-2012年电子化学细胞项目的工作。除其他外,该项目表明,电子控制的特定序列的局部转移可以用作未来人工细胞遗传增殖的人工空间控制系统,并且新陈代谢的核心过程可以通过适当的涂层电极阵列传递。

The major limitation of this approach, apart from the initial difficulties in mastering microscale electrochemistry and electrokinetics, is that the electronic system is interconnected as a rigid non-autonomous piece of macroscopic hardware. In 2011, McCaskill proposed to invert the geometry of electronics and chemistry : instead of placing chemicals in an active electronic medium, to place microscopic autonomous electronics in a chemical medium. He organized a project to tackle a third generation of Electronic Artificial Cells at the 100 µm scale that could self-assemble from two half-cells "lablets" to enclose an internal chemical space, and function with the aid of active electronics powered by the medium they are immersed in. Such cells can copy both their electronic and chemical contents and will be capable of evolution within the constraints provided by their special pre-synthesized microscopic building blocks. In September 2012 work commenced on this project.[75]

The major limitation of this approach, apart from the initial difficulties in mastering microscale electrochemistry and electrokinetics, is that the electronic system is interconnected as a rigid non-autonomous piece of macroscopic hardware. In 2011, McCaskill proposed to invert the geometry of electronics and chemistry : instead of placing chemicals in an active electronic medium, to place microscopic autonomous electronics in a chemical medium. He organized a project to tackle a third generation of Electronic Artificial Cells at the 100 µm scale that could self-assemble from two half-cells "lablets" to enclose an internal chemical space, and function with the aid of active electronics powered by the medium they are immersed in. Such cells can copy both their electronic and chemical contents and will be capable of evolution within the constraints provided by their special pre-synthesized microscopic building blocks. In September 2012 work commenced on this project.

这种方法的主要局限性,除了最初在掌握微观电化学和电动力学方面的困难之外,是电子系统作为一个刚性的非自治的宏观硬件相互连接。2011年,麦卡斯基尔提议颠倒电子学和化学的几何学: 不把化学物质放在活跃的电子介质中,而是把微观的自主电子学放在化学介质中。他组织了一个项目,以解决第三代100微米规模的电子人造细胞问题,这种细胞可以由两个半细胞”实验室”自我组装,以封闭内部化学空间,并借助浸入其中的有源电子设备发挥功能。这些细胞可以复制它们的电子和化学成分,并且能够在它们特殊的预合成微观构件所提供的约束条件下进化。2012年9月,这个项目开始了工作。

Jeewanu

Jeewanu protocells are synthetic chemical particles that possess cell-like structure and seem to have some functional living properties.[76] First synthesized in 1963 from simple minerals and basic organics while exposed to sunlight, it is still reported to have some metabolic capabilities, the presence of semipermeable membrane, amino acids, phospholipids, carbohydrates and RNA-like molecules.[76][77] However, the nature and properties of the Jeewanu remains to be clarified.[76][77][78]

Jeewanu protocells are synthetic chemical particles that possess cell-like structure and seem to have some functional living properties. First synthesized in 1963 from simple minerals and basic organics while exposed to sunlight, it is still reported to have some metabolic capabilities, the presence of semipermeable membrane, amino acids, phospholipids, carbohydrates and RNA-like molecules. However, the nature and properties of the Jeewanu remains to be clarified.

= = = Jeewanu = = = Jeewanu 原细胞是具有细胞样结构的合成化学粒子,似乎具有一些功能性的活性。1963年首次在阳光下由简单矿物质和基本有机物合成,据报道它仍然具有一些新陈代谢能力,包括半透膜、氨基酸、磷脂、碳水化合物和类 rna 分子。然而,Jeewanu 的性质和属性仍有待澄清。

See also

- Protocell

- Synthetic biology

- Artificial life

- Targeted drug delivery

- Respirocyte

- Chemoton

- Jeewanu

- Build-a-Cell

- Protocell

- Synthetic biology

- Artificial life

- Targeted drug delivery

- Respirocyte

- Chemoton

- Jeewanu

- Build-a-Cell

原细胞合成生物学人工生命靶向药物输送呼吸细胞

References

- ↑ Buddingh' BC, van Hest JC (April 2017). "Artificial Cells: Synthetic Compartments with Life-like Functionality and Adaptivity". Accounts of Chemical Research. 50 (4): 769–777. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00512. PMC 5397886. PMID 28094501.

- ↑ Deamer D (July 2005). "A giant step towards artificial life?". Trends in Biotechnology. 23 (7): 336–338. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.05.008. PMID 15935500.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Artificial cells : biotechnology, nanomedicine, regenerative medicine, blood substitutes, bioencapsulation, cell/stem cell therapy. Hackensack, N.J.: World Scientific. 2007. ISBN 978-981-270-576-1.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Artificial cells, cell engineering and therapy.. Boca Raton, Fl: Woodhead Publishing Limited. 2007. ISBN 978-1-84569-036-6.

- ↑ Polymeric materials and artificial organs based on a symposium sponsored by the Division of Organic Coatings and Plastics Chemistry at the 185th Meeting of the American Chemical Society. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society. 1983. ISBN 978-0-8412-1084-4.

- ↑ (in de) Die cellularpathologie in ihrer begründung auf physiologische und pathologische gewebelehre. Zwanzig Vorlesungen gehalten wahrend der Monate Februar, Marz und April 1858. Berlin: Verlag von August Hirschwald. 1858. p. xv. https://archive.org/details/diecellularpatho1858virc.

- ↑ Kamiya K, Takeuchi S (August 2017). "Giant liposome formation toward the synthesis of well-defined artificial cells". Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 5 (30): 5911–5923. doi:10.1039/C7TB01322A. PMID 32264347.

- ↑ Litschel T, Schwille P (May 2021). "Protein Reconstitution Inside Giant Unilamellar Vesicles". Annual Review of Biophysics. 50: 525–548. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-100620-114132. PMID 33667121. S2CID 232131463.

- ↑ Szostak JW, Bartel DP, Luisi PL (January 2001). "Synthesizing life". Nature. 409 (6818): 387–390. doi:10.1038/35053176. PMID 11201752. S2CID 4429162.

- ↑ Pohorille A, Deamer D (March 2002). "Artificial cells: prospects for biotechnology". Trends in Biotechnology. 20 (3): 123–128. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(02)01909-1. hdl:2060/20020043286. PMID 11841864.

- ↑ Noireaux V, Maeda YT, Libchaber A (March 2011). "Development of an artificial cell, from self-organization to computation and self-reproduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (9): 3473–3480. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.3473N. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017075108. PMC 3048108. PMID 21317359.

- ↑ Rasmussen S, Chen L, Nilsson M, Abe S (Summer 2003). "Bridging nonliving and living matter". Artificial Life. 9 (3): 269–316. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.101.1606. doi:10.1162/106454603322392479. PMID 14556688. S2CID 6076707.

- ↑ Gilbert W (20 February 1986). "Origin of life: The RNA world". Nature. 319 (6055): 618. Bibcode:1986Natur.319..618G. doi:10.1038/319618a0. S2CID 8026658.

- ↑ Bedau M, Church G, Rasmussen S, Caplan A, Benner S, Fussenegger M, et al. (May 2010). "Life after the synthetic cell". Nature. 465 (7297): 422–424. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..422.. doi:10.1038/465422a. PMID 20495545. S2CID 27471255.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 The ethics of protocells moral and social implications of creating life in the laboratory ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0-262-51269-5.

- ↑ "From chemicals to life: Scientists try to build cells from scratch". Retrieved 4 Dec 2019.

- ↑ "Build-a-Cell". Retrieved 4 Dec 2019.

- ↑ "FabriCell". Retrieved 8 Dec 2019.

- ↑ "MaxSynBio - Max Planck Research Network in Synthetic Biology". Retrieved 8 Dec 2019.

- ↑ "BaSyC". Retrieved 8 Dec 2019.

- ↑ "SynCell EU". Retrieved 8 Dec 2019.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang RY, Algire MA, et al. (July 2010). "Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome". Science. 329 (5987): 52–56. Bibcode:2010Sci...329...52G. doi:10.1126/science.1190719. PMID 20488990. S2CID 7320517.

- ↑ Armstrong R (September 2014). "Designing with protocells: applications of a novel technical platform". Life. 4 (3): 457–490. doi:10.3390/life4030457. PMC 4206855. PMID 25370381.

- ↑ Breuer M, Earnest TM, Merryman C, Wise KS, Sun L, Lynott MR, et al. (January 2019). "Essential metabolism for a minimal cell". eLife. 8. doi:10.7554/eLife.36842. PMC 6609329. PMID 30657448.

- ↑ Sheridan C (September 2009). "Big oil bucks for algae". Nature Biotechnology. 27 (9): 783. doi:10.1038/nbt0909-783. PMID 19741613. S2CID 205270805.

- ↑ EU Directorate-General for Health and Consumers (2016-02-12). "Opinion on synthetic biology II: Risk assessment methodologies and safety aspects" (in English). Publications Office. doi:10.2772/63529.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Chang TM (October 1964). "SEMIPERMEABLE MICROCAPSULES". Science. 146 (3643): 524–525. Bibcode:1964Sci...146..524C. doi:10.1126/science.146.3643.524. PMID 14190240. S2CID 40740134.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Chang TM (1996). "Editorial: past, present and future perspectives on the 40th anniversary of hemoglobin based red blood cell substitutes". Artificial Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 24: ixxxvi.

- ↑ Palmour RM, Goodyer P, Reade T, Chang TM (September 1989). "Microencapsulated xanthine oxidase as experimental therapy in Lesch-Nyhan disease". Lancet. 2 (8664): 687–688. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90939-2. PMID 2570944. S2CID 39716068.

- ↑ Blood substitutes. Basel: Karger. 1997. ISBN 978-3-8055-6584-4.

- ↑ Soon-Shiong P, Heintz RE, Merideth N, Yao QX, Yao Z, Zheng T, et al. (April 1994). "Insulin independence in a type 1 diabetic patient after encapsulated islet transplantation". Lancet. 343 (8903): 950–951. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90067-1. PMID 7909011. S2CID 940319.

- ↑ Liu ZC, Chang TM (June 2003). "Coencapsulation of hepatocytes and bone marrow stem cells: in vitro conversion of ammonia and in vivo lowering of bilirubin in hyperbilirubemia Gunn rats". The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 26 (6): 491–497. doi:10.1177/039139880302600607. PMID 12894754. S2CID 12447199.

- ↑ Aebischer P, Schluep M, Déglon N, Joseph JM, Hirt L, Heyd B, et al. (June 1996). "Intrathecal delivery of CNTF using encapsulated genetically modified xenogeneic cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients". Nature Medicine. 2 (6): 696–699. doi:10.1038/nm0696-696. PMID 8640564. S2CID 8049662.

- ↑ Vivier A, Vuillemard JC, Ackermann HW, Poncelet D (1992). "Large-scale blood substitute production using a microfluidizer". Biomaterials, Artificial Cells, and Immobilization Biotechnology. 20 (2–4): 377–397. doi:10.3109/10731199209119658. PMID 1391454.

- ↑ Park et al. 1981

- ↑ Chang TM (January 1971). "The in vivo effects of semipermeable microcapsules containing L-asparaginase on 6C3HED lymphosarcoma". Nature. 229 (5280): 117–118. Bibcode:1971Natur.229..117C. doi:10.1038/229117a0. PMID 4923094. S2CID 4261902.

- ↑ Yu B, Chang TM (April 2004). "Effects of long-term oral administration of polymeric microcapsules containing tyrosinase on maintaining decreased systemic tyrosine levels in rats". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 93 (4): 831–837. doi:10.1002/jps.10593. PMID 14999721.

- ↑ Meadows GG, Pierson HF, Abdallah RM, Desai PR (August 1982). "Dietary influence of tyrosine and phenylalanine on the response of B16 melanoma to carbidopa-levodopa methyl ester chemotherapy". Cancer Research. 42 (8): 3056–3063. PMID 7093952.

- ↑ Chang TM (February 2004). "Artificial cell bioencapsulation in macro, micro, nano, and molecular dimensions: keynote lecture". Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Immobilization Biotechnology. 32 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1081/bio-120028665. PMID 15027798. S2CID 37799530.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Löhr M, Hummel F, Faulmann G, Ringel J, Saller R, Hain J, et al. (May 2002). "Microencapsulated, CYP2B1-transfected cells activating ifosfamide at the site of the tumor: the magic bullets of the 21st century". Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 49 (Suppl 1): S21–S24. doi:10.1007/s00280-002-0448-0. PMID 12042985. S2CID 10329480.

- ↑ Kröger JC, Benz S, Hoffmeyer A, Bago Z, Bergmeister H, Günzburg WH, et al. (1999). "Intra-arterial instillation of microencapsulated, Ifosfamide-activating cells in the pig pancreas for chemotherapeutic targeting". Pancreatology. 3 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1159/000069147. PMID 12649565. S2CID 23711385.

- ↑ Carmen IH (April 2001). "A death in the laboratory: the politics of the Gelsinger aftermath". Molecular Therapy. 3 (4): 425–428. doi:10.1006/mthe.2001.0305. PMID 11319902.

- ↑ Raper SE, Chirmule N, Lee FS, Wivel NA, Bagg A, Gao GP, et al. (1 September 2003). "Fatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in a ornithine transcarbamylase deficient patient following adenoviral gene transfer". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 80 (1–2): 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.016. PMID 14567964.

- ↑ Cavazzana-Calvo M, Hacein-Bey S, de Saint Basile G, Gross F, Yvon E, Nusbaum P, et al. (April 2000). "Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease". Science. 288 (5466): 669–672. Bibcode:2000Sci...288..669C. doi:10.1126/science.288.5466.669. PMID 10784449.

- ↑ Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, et al. (October 2003). "LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1". Science. 302 (5644): 415–419. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..415H. doi:10.1126/science.1088547. PMID 14564000. S2CID 9100335.

- ↑ Chang PL, Van Raamsdonk JM, Hortelano G, Barsoum SC, MacDonald NC, Stockley TL (February 1999). "The in vivo delivery of heterologous proteins by microencapsulated recombinant cells". Trends in Biotechnology. 17 (2): 78–83. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(98)01250-5. PMID 10087608.