大气模式

此词条暂由彩云小译翻译,翻译字数共2959,未经人工整理和审校,带来阅读不便,请见谅。

大气模式 atmospheric model是围绕控制大气运动的一整套原始的动力学方程所建立的数学模型。它可以通过湍流扩散、辐射、湿过程(云和降水)、热交换、土壤、植被、地表水、地形的动力学效应和对流等的参数化来补充这些方程。大多数大气模式是基于数值方法的,即将运动方程离散化。它们可以预测微尺度的现象,例如龙卷风、边界层的涡旋、流经建筑物上方的亚微尺度湍流,以及天气气流、全球气流。模式的水平区域全球性的,覆盖整个地球,也可以是区域性的(有限区域的),只覆盖部分地球。模式运行的不同类型包括热致的、正压的、流体静力学的和非流体静力学的。部分类型的模式对大气进行了一些假设,从而加长了时间步长并提高计算速度。

预报是使用大气物理和动力学方程计算得来的。这些方程是非线性的,无法获得准确解。因此只能使用数值方法获得近似解。不同的模式使用不同的求解方法。全球模式通常在水平维度上采用谱方法,而在垂直维度采用有限差分法;而区域模式通常在三个维度均使用有限差分法。对于特定的位置,模式的输出统计使用气候信息、数值天气预测结果以及当前地表天气观测数据来建立统计关系,以解释模式偏差和分辨率问题。

类型

The main assumption made by the thermotropic model is that while the magnitude of the thermal wind may change, its direction does not change with respect to height, and thus the baroclinicity in the atmosphere can be simulated using the 模板:Convert and 模板:Convert geopotential height surfaces and the average thermal wind between them.

由热致模式作出的主要假设是,热风的大小可以改变,但方向不随高度变化,因此大气的斜压性可以用位势高度面和它们之间的平均热风来模拟。[1][2]

正压 Barotropic模式假定大气接近正压,这意味着地转风的方向和速度与高度无关,即地转风无垂直切变。这也意味着温度的厚度等值线平行于上层高度等值线。在这种类型的大气中,高压区和低压区是冷暖温度异常的中心。暖心高压(如亚热带脊线和百慕大-亚速尔高压)和冷心低压具有随高度增强的风力,而冷心高压(北极浅层高压)和暖心低压(如热带气旋)则相反。[3]正压模式试图基于大气处于地转平衡的假设(即空气中的罗斯比数小)来解决简化形式的大气动力学问题。[4]如果假设大气无散度,则欧拉方程的旋度简化为正压涡度方程,后者可以在一层大气上求解。由于大气在大约5.5 千米(3.4 英里)处几乎无旋度,正压模式最接近大气在对应海拔处的位势高度时的状态,该海拔与大气压力面有关。[5]

流体静力学 Hydrostatic模式从垂直动量方恒中过滤出垂直运动的声波,这显著地增加了模型运行中使用的时间步长,这就是流体静力学近似。流体静力学模式使用压力或sigma压力作为垂直坐标。压力坐标与地形相交,而sigma坐标随地形等高线变化。只要水平网格分辨率不小,该模式的流体静力学假设便是合理的。使用整个垂直动量方程的模式称为 非流体静力学模式 nonhydrostatic model,它既可以滞弹性求解,这意味着它求解了不可压缩空气的完整的连续性方程;也可以弹性求解,这意味着它求解了完全可压缩空气的完整的连续性方程。非静力学假设使用海拔高度或sigma高度作为其垂直坐标。海拔高度可以和地形相交,而sigma 高度坐标随地面等高线改变。[6]

历史

数值天气预报的历史起于20世纪20年代,这得益于 Lewis Fry Richardson 使用了 Vihelm Bjerknes 开发的方法的成果。[7][8]直到计算机和计算机模拟时代的到来,计算时间才降低到少于被预测时段。ENIAC 在1950年发明了第一台计算机预测系统,[5][9]之后功能更强大的计算机增加了初始数据集的规模,并包含了更复杂的运动方程的版本。[10]1966年,西德和美国开始根据原始方程模式制作业务预测系统,1972年英国和1977年澳大利亚紧随其后。[7][11] 全球预报模式的发展导致了第一个气候模式的诞生。[12][13]在20世纪70年代和20世纪80年代,有限区域(区域性)模式的发展推动了热带气旋轨道和空气质量预报的进步。[14][15]

由于基于大气动力学的预报模式的输出结果需要近地面处的修正,因此20世纪70年代和20世纪80年代开发了单个预报位点的模式输出统计(MOS)。[16][17]尽管超级计算机的能力不断提升,数值天气模式的预报仅能延伸到未来两周左右,这是因为观测点的密度和质量以及被用来预测的偏微分方程的混沌本质都会引入每五天加倍的误差。[18][19]自20世纪90年代以来,模式集合预报的使用帮助确定了不确定性,并且预测时段比其他可能的方式都要长。[20][21][22]

初始化

大气是流动的。因此,数值天气预报的思想是对给定时间的流体状态进行采样,并使用流体动力学和热力学方程来估计未来某个时间的流体状态。将观测数据输入模型以生成初始条件的过程称为初始化。在陆地上,全球分辨率低至1公里(0.6英里)的地形图用于帮助模拟崎岖地形区域内的大气环流,以便更好地描述影响入射太阳辐射的下坡风、过山波和相关云量等特征。基于国家的气象服务的主要输入是来自气象气球上的设备(称为无线电探空仪)的观测,这些设备测量各种大气参数并将其传输到固定接收器,以及来自气象卫星的观测。世界气象组织(World Meteorological Organization)在全球范围内对仪器、观测实践和观测时间进行标准化。观测站在METAR报告中每小时报告一次,或者在SYNOP报告中每六小时报告一次。这些观测数据的间隔不规则,因此通过数据同化和客观分析方法进行处理,以实现质量控制并在模型数学算法可用的位置获取数值,使得最后在模式中被用作预测的起点。

有许多方法可以收集数值模型的观测数据。这些站点通过从对流层上升到平流层的气象气球来发射无线电探空仪。在传统数据源不可用的情况下,则可以使用气象卫星提供的信息。商务部提供飞机航线上的飞行员报告和航运航线上的船舶报告。研究项目使用侦察机在关注的天气系统内和周围飞行,如热带气旋。在寒冷季节,侦察机也会飞越公海,进入一些对预报制导造成重大不确定性、预计在未来三到七天内对下游大陆产生重大影响的系统中。1971年,海冰开始在预报模型中得到初始化。1972年,由于海洋表面温度在调节太平洋高纬度地区天气方面的作用,将其纳入模型初始化的工作也开始进行。

计算

文件:Supercomputing the Climate.ogv

模式指的是一种可以在给定的位置和海拔高度生成未来气象信息的一种计算机程序。任何模型中都有一套称为“原始方程组”的方程组,用于预测未来的大气状态。这些方程组依据分析数据初始化,并确定变化速率。这些变化速率可以预测未来一小段时间的大气状态,每一个时间增量被称为一个时间步长。然后这些方程组被用于新的大气状态,得到新的变化速率,新的变化速率接着被用于预测再往后的大气状态。[23]不断推进时间步,直到方程组的解到达了想要的预测时间。模式内时间步长的选择与计算网格间距有关,需要确保数值稳定性。[24]全球模式的时间步长约为数十分钟,[25]而区域模式则为1到4分钟。[26]全球模式预测时段各有不同。UKMET联合模式可预测未来6天,[27]欧洲中心的中程天气预测模式 European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts model可预测未来10天,[28]而环境建模中心 Environmental Modeling Center的全球预测系统模式 Global Forest System model可以预测未来16天。[29]

由于使用的方程组是非线性的偏微分方程组,[30]除了少数理想情况外无法用解析方法得到准确解,[31]因此使用数值方法来获得近似解。不同的模式使用不同的求解方法:一些全球模式在水平维度使用谱方法求解,在垂直维度使用有限差分方法求解;而另一些全球模式以及区域模式则在三个维度都使用有限差分方法求解。[30]模式的结果可视化通常称为预测图,或简称为“prog”。[32]

参数化

天气和气象模式网格具有5千米(3.1英里)到300千米(190英里)之间的边界。典型的积云尺度小于1千米(0.62英里),因此需要比这更精细的网格才能被流体运动方程表示。故而,这些云所代表的过程是通过各种复杂的处理来表示的。最早的模式中,如果模式中的空气柱是不稳定的(即底部比顶部热),那么它将被破坏,该垂直柱中的空气将被混合。更加复杂的模式中有增强功能,它们知道整个网格中只有一部分会发生对流、夹带或者一些其它过程。边界在5千米(3.1英里)到25千米(16英里)的气象模式可以明确地表示对流云,尽管它们仍然需要参数化云的微物理过程。[33]大尺度(层云型)云的形成更加基于物理规律,它们在相对湿度达到某个规定值时形成。此时仍然有亚网格尺寸的过程也需要被考虑进来。层云形成的临界湿度被设定为70%而不是100%,相对湿度超过80%时认为形成的是积云,[34]这反应了现实世界中可能发生的亚网格尺寸的变化。

在崎岖的地形中或云量多变地区达到地面的太阳辐射量也被参数化了,因为该过程发生在分子尺寸。[35] 并且,模型的网格尺寸相对于实际的云和地形的尺寸及粗糙度都要大得多。太阳角度以及其对多个云层的影响均被考虑在内。[36]土壤类型、植被类型以及土壤湿度均决定了多少辐射参与邻近大气的加热以及湿度的增加。因此,它们也是重要的需要参数化的量。[37]

范围

一个模式的水平范围可以是全球性的,覆盖整个地球;也可以是区域性的,只覆盖地球的一部分。区域模式也被称为有限区域模式(LAMs)。区域模式使用更加精细的网格来明确地解决较小尺度的气象现象,因为它们更小的水平范围降低了计算量的要求。区域模式使用一个兼容的全球模式来获得区域模式边界处的初始条件。用以获得区域模式的边界条件的全球模式,以及区域模式本身创造的边界条件,共同引入区域模式的的不确定度和误差。[38]

垂直坐标有多种方式处理。一些模式,如Richardson的1922模式,使用几何高度(z)作为垂直坐标。后来的模式使用压力坐标系代替了几何z坐标系,从而等压面的位势高度变成了因变量,极大地简化了原始方程组。[39] 这是因为地球大气层的压力随着高度增加而降低。[40]第一个用于业务预报的模式,即单层正压模式,在500mbar水平面上使用一个简单的压力坐标,[5]并因此基本上是二维的。高分辨率模式(也被称为中尺度模式),如WRF模式,则往往使用标准化压力坐标(sigma坐标)。[41]

全球模式版本

一些比较著名的全球数值模式有:

- GFS 全球预测系统(Global Forecast System,前身为AVN)——由NOAA开发

- NOGAPS ——由美国海军开发,用于和GFS比对

- GEM 全球环境多尺度模式(Global Environmental Multiscale Model)——由加拿大气象局(MSC)开发

- IFS 由欧洲中心的中程度天气预测部门(the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts)开发

- UM 统一模式(Unified Model),由英国气象办公室(the UK Met Office)

- ICON 由德国天气局、DWD以及马普所(MPI)气象部门(汉堡)联合开发

- ARPEGE 由法国天气局开发(the French Weather Service, Météo-France)

- IGCM 中间大气环流模式(Intermediate General Circulation Model)

区域模式版本

一些比较著名的区域数值模式有:

- WRF 天气研究与预测模式(the Weather Research and Forecasting model),由NCEP、NCAR以及气象研究社区共同开发。WRF有多种配置,比如:

- WRF-NMM WRF非流体静力学中尺度模式(the WRF Nonhydrostatic Mesoscale Model),这是美国主要的短期天气预测模式,用于替代Eta模式

- WRF-ARW 主要由NCAR开发的高级研究WRF(Advanced Research WRF)

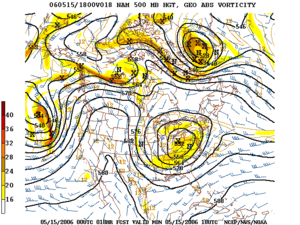

- NAM 北美中尺度模式(North American Mesoscale model),指的是 NCEP 在北美地区运作的任何区域模式。NCEP 于2005年1月开始使用这一称呼系统。2005年1月至2006年5月期间,Eta 模式使用了这一称号。从2006年5月开始,NCEP 开始使用 WRF-NMM 作为业务预报中的北美中尺度模式。

- RAMS 区域大气模拟系统(the Regional Atmospheric Modeling System)由科罗拉多州立大学开发,用于从数米到数百公里范围内的大气气象和其他环境现象的数值模拟,现已得到公共领域的支持

- MM5 第五代宾夕法尼亚州立大学/NCAR 中尺度模式(the Fifth Generation Penn State/NCAR Mesoscale Model)

- ARPS 奥克拉荷马大学开发的高级区域预报系统(the Advanced Region Prediction System)是一个综合性的多尺度非流体静力学的模拟和预报系统,应用范围从区域尺度的天气预报,到龙卷尺度的模拟和预报。用于雷暴预报的高级雷达数据同化是该系统的关键部分。

- HIRLAM 高分辨率有限区域模式(High Resolution Limited Area Model),由欧洲数值天气预报研究联盟 HIRLAM 开发,由10个欧洲气象部门共同资助。中尺度的 HIRLAM 模式被称为 HARMONIE,是 Meteo France 和 ALADIN 联盟合作开发的。

- GEM-LAM 全球环境多尺度有限区域模式(Global Environmental Multiscale Limited Area Model),由加拿大气象局开发的高分辨率(2.5千米,约1.6英里)的 GEM。

- ALADIN 高分辨率有限区域流体静力学和非流体静力学模式(the high-resolution limited-area hydrostatic and non-hydrostatic model),由欧洲和北非的一些国家在 Météo-France 领导下开发和运行

- COSMO 模式,以前称为 LM,aLMo 或 LAMI,是在小尺度模式联合会(德国、瑞士、意大利、希腊、波兰、罗马尼亚和俄罗斯)框架内开发的有限区域非流体静力学模式。

- Meso-NH Meso-NH 模式是有限区域非流体静力学模式,自1998年来由法国国家气象研究中心和航空实验室(法国,图卢兹)联合开发,其应用领域包括从中尺度到厘米尺度的天气模拟。

Model output statistics 模式输出统计

Because forecast models based upon the equations for atmospheric dynamics do not perfectly determine weather conditions near the ground, statistical corrections were developed to attempt to resolve this problem. Statistical models were created based upon the three-dimensional fields produced by numerical weather models, surface observations, and the climatological conditions for specific locations. These statistical models are collectively referred to as model output statistics (MOS),[42] and were developed by the National Weather Service for their suite of weather forecasting models.[16] The United States Air Force developed its own set of MOS based upon their dynamical weather model by 1983.[17]

Because forecast models based upon the equations for atmospheric dynamics do not perfectly determine weather conditions near the ground, statistical corrections were developed to attempt to resolve this problem. Statistical models were created based upon the three-dimensional fields produced by numerical weather models, surface observations, and the climatological conditions for specific locations. These statistical models are collectively referred to as model output statistics (MOS), and were developed by the National Weather Service for their suite of weather forecasting models. The United States Air Force developed its own set of MOS based upon their dynamical weather model by 1983.

由于基于大气动力学方程式的预报模式不能完全确定近地天气状况,因此开发了统计修正以试图解决这一问题。基于数值天气模型、地面观测和特定地点的气候条件产生的三维场,建立了统计模型。这些统计模型统称为模型输出统计(MOS) ,由国家气象局为他们的一套天气预报模型开发。到1983年,美国空军根据其动态天气模型开发了自己的一套 MOS。

【终稿】由于基于大气动力学方程的预报模式无法完美地决定近地天气状况,人们开发了统计修正的方法来尝试解决这个问题。统计模型基于数值天气模式、地面观测站、特定地点的气候条件产生的三维场。这些统计模型被统称为模式输出统计(MOS),并由美国国家气象局开发为一套完整的天气预报模式。美国空军在1983年根据其动态天气模式开发了自己的MOS。

Model output statistics differ from the perfect prog technique, which assumes that the output of numerical weather prediction guidance is perfect.[43] MOS can correct for local effects that cannot be resolved by the model due to insufficient grid resolution, as well as model biases. Forecast parameters within MOS include maximum and minimum temperatures, percentage chance of rain within a several hour period, precipitation amount expected, chance that the precipitation will be frozen in nature, chance for thunderstorms, cloudiness, and surface winds.[44]

Model output statistics differ from the perfect prog technique, which assumes that the output of numerical weather prediction guidance is perfect. MOS can correct for local effects that cannot be resolved by the model due to insufficient grid resolution, as well as model biases. Forecast parameters within MOS include maximum and minimum temperatures, percentage chance of rain within a several hour period, precipitation amount expected, chance that the precipitation will be frozen in nature, chance for thunderstorms, cloudiness, and surface winds.

模型输出统计不同于完美的前端技术,前端技术假设数值天气预报指导的输出是完美的。MOS 可以修正由于网格分辨率不足以及模型偏差而无法由模型解决的局部效应。MOS 内的预报参数包括最高和最低气温、几个小时内降雨的百分比、预期降水量、降水在自然界结冰的可能性、雷暴的可能性、云量和地面风。

【终稿】模型输出统计不同于完美的预测图(prog),后者假定数值天气预报指导的输出是完美的。而MOS可以修正因网格分辨率不足以及模型偏差等模式无法解决的局地效应。MOS中的预报参数包括最高和最低温度、未来数小时降雨可能性、预期降水量、降水在自然界中结冰的可能性、雷暴可能性、云量和地面风。

Applications

Applications 应用

Climate modeling 气候模拟

In 1956, Norman Phillips developed a mathematical model that realistically depicted monthly and seasonal patterns in the troposphere. This was the first successful climate model.[12][13] Several groups then began working to create general circulation models.[45] The first general circulation climate model combined oceanic and atmospheric processes and was developed in the late 1960s at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, a component of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.[46] By the early 1980s, the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research had developed the Community Atmosphere Model (CAM), which can be run by itself or as the atmospheric component of the Community Climate System Model. The latest update (version 3.1) of the standalone CAM was issued on 1 February 2006.[47][48][49] In 1986, efforts began to initialize and model soil and vegetation types, resulting in more realistic forecasts.[50] Coupled ocean-atmosphere climate models, such as the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research's HadCM3 model, are being used as inputs for climate change studies.[45]

In 1956, Norman Phillips developed a mathematical model that realistically depicted monthly and seasonal patterns in the troposphere. This was the first successful climate model. Several groups then began working to create general circulation models. The first general circulation climate model combined oceanic and atmospheric processes and was developed in the late 1960s at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, a component of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. By the early 1980s, the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research had developed the Community Atmosphere Model (CAM), which can be run by itself or as the atmospheric component of the Community Climate System Model. The latest update (version 3.1) of the standalone CAM was issued on 1 February 2006. In 1986, efforts began to initialize and model soil and vegetation types, resulting in more realistic forecasts. Coupled ocean-atmosphere climate models, such as the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research's HadCM3 model, are being used as inputs for climate change studies.

1956年,诺曼 · 菲利普斯开发了一个数学模型,这个模型真实地描述了对流层的每月和季节的模式。这是第一个成功的气候模型。几个小组随后开始建立大体循环模型。第一个大气环流气候模式结合了海洋和大气过程,于20世纪60年代末在美国地球物理流体动力学实验室气候研究中心发展起来,该中心是美国美国国家海洋和大气管理局气候研究中心的一个组成部分。到20世纪80年代早期,美国国家大气研究中心开发了社区大气模型(CAM) ,它可以自己运行,也可以作为社区气候系统模型的大气成分。最新更新(3.1版本)已于2006年2月1日发出。在1986年,开始努力初始化和模型的土壤和植被类型,导致更现实的预测。耦合的海洋-大气气候模型,如哈德利气候预测与研究中心的 hadcm3模型,正被用作气候变化研究的输入。

【终稿】1956年,诺曼·菲利普斯(Norman Phillips)开发了一个真实描述对流层逐月和逐季节模式的数学模型。这是第一个成功的气候模式。几个小组随后开始开创大气循环模式。20世纪60年代,第一个耦合海洋和大气过程的循环气候模式在美国地球物理流体动力学实验室气候研究中心被开发出来,该中心是美国美国国家海洋和大气管理局气候研究中心的一个分部门。到20世纪80年代早期,美国国家大气研究中心开发了社区大气模式(CAM) ,既可以单独运行,也可以作为社区气候系统模型的大气模块部分运行。最新的独立CAM(3.1版本)已于2006年2月1日发布。在1986年,人们开始投入初始化和模拟的土壤、植被类型,以实现更真实的预测。耦合的海洋-大气气候模式,如哈德利气候预测与研究中心的 HadCM3模式(the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research's HadCM3 model),正被用作气候变化研究的输入。

Limited area modeling 有限区域模拟

Air pollution forecasts depend on atmospheric models to provide fluid flow information for tracking the movement of pollutants.[51] In 1970, a private company in the U.S. developed the regional Urban Airshed Model (UAM), which was used to forecast the effects of air pollution and acid rain. In the mid- to late-1970s, the United States Environmental Protection Agency took over the development of the UAM and then used the results from a regional air pollution study to improve it. Although the UAM was developed for California, it was during the 1980s used elsewhere in North America, Europe, and Asia.[15]

Air pollution forecasts depend on atmospheric models to provide fluid flow information for tracking the movement of pollutants. In 1970, a private company in the U.S. developed the regional Urban Airshed Model (UAM), which was used to forecast the effects of air pollution and acid rain. In the mid- to late-1970s, the United States Environmental Protection Agency took over the development of the UAM and then used the results from a regional air pollution study to improve it. Although the UAM was developed for California, it was during the 1980s used elsewhere in North America, Europe, and Asia.

空气污染预报依靠大气模型来提供流体流动信息,以跟踪污染物的运动。1970年,美国的一家私营公司开发了区域城市气流模型(UAM) ,用于预测空气污染和酸雨的影响。在1970年代中后期,美国环境保护局接管了 UAM 的开发工作,然后利用区域空气污染研究的结果来改进 UAM。虽然 UAM 是为加利福尼亚州开发的,但在20世纪80年代,它在北美、欧洲和亚洲的其他地方得到了应用。

【终稿】空气污染预报依靠大气模式来提供流体流动信息,从而跟踪污染物运动。1970年,美国的一家私营公司开发了区域城市气流模式(the regional Urban Airshed Model,UAM),用于预报空气污染及酸雨的影响。在20世纪70年代年代中后期,美国环境保护局接管了UAM的开发工作,并利用区域空气污染研究的结果对其改进。尽管UAM是为加利福利亚州开发的,但到了20世纪80年代,它在北美、欧洲和亚洲的部分地区投入应用。

The Movable Fine-Mesh model, which began operating in 1978, was the first tropical cyclone forecast model to be based on atmospheric dynamics.[14] Despite the constantly improving dynamical model guidance made possible by increasing computational power, it was not until the 1980s that numerical weather prediction (NWP) showed skill in forecasting the track of tropical cyclones. And it was not until the 1990s that NWP consistently outperformed statistical or simple dynamical models.[52] Predicting the intensity of tropical cyclones using NWP has also been challenging. As of 2009, dynamical guidance remained less skillful than statistical methods.[53]

The Movable Fine-Mesh model, which began operating in 1978, was the first tropical cyclone forecast model to be based on atmospheric dynamics. Despite the constantly improving dynamical model guidance made possible by increasing computational power, it was not until the 1980s that numerical weather prediction (NWP) showed skill in forecasting the track of tropical cyclones. And it was not until the 1990s that NWP consistently outperformed statistical or simple dynamical models. Predicting the intensity of tropical cyclones using NWP has also been challenging. As of 2009, dynamical guidance remained less skillful than statistical methods.

可移动细网模型于1978年开始运行,是第一个基于大气动力学的热带气旋预报模型模型。尽管由于计算能力的提高,不断改进的动力学模型指南成为可能,但直到20世纪80年代,数值天气预报才显示出预报热带气旋路径的技术。直到20世纪90年代,数值天气预报才始终优于统计或简单的动力学模型。使用数值预报方法预报热带气旋的强度也是一个挑战。截至2009年,动态指导仍然不如统计方法熟练。

【终稿】可移动细网格模式(the Movable Fine-Mesh model)在1978年开始运行,是第一个基于大气动力学的热带气旋预报模式。尽管由于不断增强的计算机算力,持续改进的动力学模式指导成为可能,但是直到20世纪80年代,数值天气预报才显示出预报热带气旋路径的能力;直到20世纪90年代才持续地好于统计模型或简单的动力学模型。使用数值预报方法预测热带气旋强调也始终难度较高。直到2009年,动力学控制的方法仍不如统计方法效果好。

See also 另见

- Atmospheric reanalysis

- Climate model

- Numerical weather prediction

- Upper-atmospheric models

- Static atmospheric model

- Atmospheric reanalysis

- Climate model

- Numerical weather prediction

- Upper-atmospheric models

- Static atmospheric model

【终稿】

- 大气再分析

- 气候模式

- 数值天气预报

- 高层大气模式

- 稳定大气模式

= = =

- 大气重新分析

- 气候模式

- 数值天气预报

- 高层大气模式

- 静态大气模式

References

- ↑ Gates, W. Lawrence (August 1955). Results Of Numerical Forecasting With The Barotropic And Thermotropic Atmospheric Models. Hanscom Air Force Base: Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratories. http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/AD101943.

- ↑ Thompson, P. D.; W. Lawrence Gates (April 1956). "A Test of Numerical Prediction Methods Based on the Barotropic and Two-Parameter Baroclinic Models". Journal of Meteorology. 13 (2): 127–141. Bibcode:1956JAtS...13..127T. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1956)013<0127:ATONPM>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0469.

- ↑ Wallace, John M.; Peter V. Hobbs (1977). Atmospheric Science: An Introductory Survey. Academic Press, Inc.. pp. 384–385. ISBN 978-0-12-732950-5.

- ↑ Marshall, John; Plumb, R. Alan (2008). "Balanced flow". Atmosphere, ocean, and climate dynamics : an introductory text. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 109–12. ISBN 978-0-12-558691-7.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Charney, Jule; Fjörtoft, Ragnar; von Neumann, John (November 1950). "Numerical Integration of the Barotropic Vorticity Equation". Tellus. 2 (4): 237–254. Bibcode:1950TellA...2..237C. doi:10.3402/tellusa.v2i4.8607.

- ↑ Jacobson, Mark Zachary (2005). Fundamentals of atmospheric modeling. Cambridge University Press. pp. 138–143. ISBN 978-0-521-83970-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=41qztAEACAAJ.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Lynch, Peter (2008-03-20). "The origins of computer weather prediction and climate modeling" (PDF). Journal of Computational Physics. 227 (7): 3431–44. Bibcode:2008JCoPh.227.3431L. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2007.02.034. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-08. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- ↑ Lynch, Peter (2006). "Weather Prediction by Numerical Process". The Emergence of Numerical Weather Prediction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN 978-0-521-85729-1.

- ↑ Cox, John D. (2002). Storm Watchers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-471-38108-2. https://archive.org/details/stormwatcherstur00cox_df1/page/208.

- ↑ Harper, Kristine; Uccellini, Louis W.; Kalnay, Eugenia; Carey, Kenneth; Morone, Lauren (May 2007). "2007: 50th Anniversary of Operational Numerical Weather Prediction". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 88 (5): 639–650. Bibcode:2007BAMS...88..639H. doi:10.1175/BAMS-88-5-639.

- ↑ Leslie, L.M.; Dietachmeyer, G.S. (December 1992). "Real-time limited area numerical weather prediction in Australia: a historical perspective" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. Bureau of Meteorology. 41 (SP): 61–77. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Norman A. Phillips (April 1956). "The general circulation of the atmosphere: a numerical experiment" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 82 (352): 123–154. Bibcode:1956QJRMS..82..123P. doi:10.1002/qj.49708235202.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 John D. Cox (2002). Storm Watchers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-471-38108-2. https://archive.org/details/stormwatcherstur00cox_df1/page/210.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Shuman, Frederick G. (September 1989). "History of Numerical Weather Prediction at the National Meteorological Center". Weather and Forecasting. 4 (3): 286–296. Bibcode:1989WtFor...4..286S. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1989)004<0286:HONWPA>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Steyn, D. G. (1991). Air pollution modeling and its application VIII, Volume 8. Birkhäuser. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-306-43828-8.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Harry Hughes (1976). Model output statistics forecast guidance. United States Air Force Environmental Technical Applications Center. pp. 1–16.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 L. Best, D. L.; S. P. Pryor (1983). Air Weather Service Model Output Statistics Systems. Air Force Global Weather Central. pp. 1–90.

- ↑ Cox, John D. (2002). Storm Watchers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. pp. 222–224. ISBN 978-0-471-38108-2. https://archive.org/details/stormwatcherstur00cox_df1/page/222.

- ↑ Weickmann, Klaus, Jeff Whitaker, Andres Roubicek and Catherine Smith (2001-12-01). The Use of Ensemble Forecasts to Produce Improved Medium Range (3–15 days) Weather Forecasts. Climate Diagnostics Center. Retrieved 2007-02-16.

- ↑ Toth, Zoltan; Kalnay, Eugenia (December 1997). "Ensemble Forecasting at NCEP and the Breeding Method". Monthly Weather Review. 125 (12): 3297–3319. Bibcode:1997MWRv..125.3297T. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.324.3941. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1997)125<3297:EFANAT>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493.

- ↑ "The Ensemble Prediction System (EPS)". ECMWF. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ↑ Molteni, F.; Buizza, R.; Palmer, T.N.; Petroliagis, T. (January 1996). "The ECMWF Ensemble Prediction System: Methodology and validation". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 122 (529): 73–119. Bibcode:1996QJRMS.122...73M. doi:10.1002/qj.49712252905.

- ↑ Pielke, Roger A. (2002). Mesoscale Meteorological Modeling. Academic Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-12-554766-6.

- ↑ Pielke, Roger A. (2002). Mesoscale Meteorological Modeling. Academic Press. pp. 285–287. ISBN 978-0-12-554766-6.

- ↑ Sunderam, V. S.; G. Dick van Albada; Peter M. A. Sloot; J. J. Dongarra (2005). Computational Science – ICCS 2005: 5th International Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, May 22–25, 2005, Proceedings, Part 1. Springer. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-540-26032-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=JZikIbXzipwC&pg=PA131.

- ↑ Zwieflhofer, Walter; Norbert Kreitz; European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (2001). Developments in teracomputing: proceedings of the ninth ECMWF Workshop on the Use of High Performance Computing in Meteorology. World Scientific. p. 276. ISBN 978-981-02-4761-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=UV6PnF2z5_wC&pg=PA276.

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为models的引用提供文字 - ↑ Holton, James R. (2004). An introduction to dynamic meteorology, Volume 1. Academic Press. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-12-354015-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=fhW5oDv3EPsC&pg=PA474.

- ↑ Brown, Molly E. (2008). Famine early warning systems and remote sensing data. Springer. p. 121. ISBN 978-3-540-75367-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=mTZvR3R6YdkC&pg=PA121.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Strikwerda, John C. (2004). Finite difference schemes and partial differential equations. SIAM. pp. 165–170. ISBN 978-0-89871-567-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=SH8R_flZBGIC&pg=PA165.

- ↑ Pielke, Roger A. (2002). Mesoscale Meteorological Modeling. Academic Press. pp. 65. ISBN 978-0-12-554766-6.

- ↑ Ahrens, C. Donald (2008). Essentials of meteorology: an invitation to the atmosphere. Cengage Learning. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-495-11558-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=2Yn29IFukbgC&pg=PA244.

- ↑ Narita, Masami & Shiro Ohmori (2007-08-06). "3.7 Improving Precipitation Forecasts by the Operational Nonhydrostatic Mesoscale Model with the Kain-Fritsch Convective Parameterization and Cloud Microphysics" (PDF). 12th Conference on Mesoscale Processes. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ Frierson, Dargan (2000-09-14). "The Diagnostic Cloud Parameterization Scheme" (PDF). University of Washington. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ Stensrud, David J. (2007). Parameterization schemes: keys to understanding numerical weather prediction models. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-521-86540-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=lMXSpRwKNO8C&pg=PA56.

- ↑ Melʹnikova, Irina N.; Alexander V. Vasilyev (2005). Short-wave solar radiation in the earth's atmosphere: calculation, oberservation, interpretation. Springer. pp. 226–228. ISBN 978-3-540-21452-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=vdg5BgBmMkQC&pg=PA226.

- ↑ Stensrud, David J. (2007). Parameterization schemes: keys to understanding numerical weather prediction models. Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-0-521-86540-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=lMXSpRwKNO8C&pg=PA56.

- ↑ Warner, Thomas Tomkins (2010). Numerical Weather and Climate Prediction. Cambridge University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-521-51389-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=6RQ3dnjE8lgC&pg=PA261.

- ↑ Lynch, Peter (2006). "The Fundamental Equations". The Emergence of Numerical Weather Prediction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-521-85729-1.

- ↑ Ahrens, C. Donald (2008). Essentials of meteorology: an invitation to the atmosphere. Cengage Learning. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-495-11558-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=2Yn29IFukbgC&pg=PA244.

- ↑ Janjic, Zavisa; Gall, Robert; Pyle, Matthew E. (February 2010). "Scientific Documentation for the NMM Solver" (PDF). National Center for Atmospheric Research. pp. 12–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-23. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ↑ Baum, Marsha L. (2007). When nature strikes: weather disasters and the law. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-275-22129-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=blEMoIKX_0IC&pg=PA188.

- ↑ Gultepe, Ismail (2007). Fog and boundary layer clouds: fog visibility and forecasting. Springer. p. 1144. ISBN 978-3-7643-8418-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=QwzHZ-wV-BAC&pg=PA1144.

- ↑ Barry, Roger Graham; Richard J. Chorley (2003). Atmosphere, weather, and climate. Psychology Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-415-27171-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Xs9LiGpNX-AC&pg=PA171.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Peter Lynch (2006). "The ENIAC Integrations". The Emergence of Numerical Weather Prediction: Richardson's Dream. Cambridge University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-521-85729-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=EV5bZqOO7kkC&pg=PA208.

- ↑ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (22 May 2008). "The First Climate Model". Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ↑ "CAM 3.1 Download". www.cesm.ucar.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- ↑ William D. Collins; et al. (June 2004). "Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 3.0)" (PDF). University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ↑ "CAM3.0 COMMUNITY ATMOSPHERE MODEL". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ↑ Yongkang Xue & Michael J. Fennessey (20 March 1996). "Impact of vegetation properties on U. S. summer weather prediction" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 101 (D3): 7419. Bibcode:1996JGR...101.7419X. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.453.551. doi:10.1029/95JD02169. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ Alexander Baklanov; Alix Rasmussen; Barbara Fay; Erik Berge; Sandro Finardi (September 2002). "Potential and Shortcomings of Numerical Weather Prediction Models in Providing Meteorological Data for Urban Air Pollution Forecasting". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution: Focus. 2 (5): 43–60. doi:10.1023/A:1021394126149. S2CID 94747027.

- ↑ James Franklin (20 April 2010). "National Hurricane Center Forecast Verification". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ Edward N. Rappaport; James L. Franklin; Lixion A. Avila; Stephen R. Baig; John L. Beven II; Eric S. Blake; Christopher A. Burr; Jiann-Gwo Jiing; Christopher A. Juckins; Richard D. Knabb; Christopher W. Landsea; Michelle Mainelli; Max Mayfield; Colin J. McAdie; Richard J. Pasch; Christopher Sisko; Stacy R. Stewart; Ahsha N. Tribble (April 2009). "Advances and Challenges at the National Hurricane Center". Weather and Forecasting. 24 (2): 395–419. Bibcode:2009WtFor..24..395R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.207.4667. doi:10.1175/2008WAF2222128.1.

Further reading 进一步阅读

- Roulstone, Ian; Norbury, John (2013). Invisible in the Storm: the role of mathematics in understanding weather. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15272-1.

External links

- WRF Source Codes and Graphics Software Download Page

- RAMS source code available under the GNU General Public License

- MM5 Source Code download

- The source code of ARPS

- Model Visualisation

- WRF Source Codes and Graphics Software Download Page

- RAMS source code available under the GNU General Public License

- MM5 Source Code download

- The source code of ARPS

- Model Visualisation

外部链接

Categories: Numerical climate and weather models

【终稿】数值气候与天气模式

模板:Atmospheric, Oceanographic and Climate Models 模板:Computer modeling

Category:Numerical climate and weather models

Category:Articles containing video clips

类别: 数值气候和天气模型类别: 包含视频剪辑的文章

This page was moved from wikipedia:en:Atmospheric model. Its edit history can be viewed at 大气模式/edithistory