生物地球化学循环

生物地球化学循环 biogeochemical cycle是化学物质在地球的生物隔室和非生物隔室中进行循环(被转化或穿过)的过程。生物隔室指生物圈,非生物隔室指大气圈、水圈和岩石圈。其包括化学元素的生物地球化学循环,如钙、碳、氢、汞、氮、氧、磷、硒、铁和硫,以及分子循环,如水和硅。同时也包括宏观循环,如岩石的循环,以及人为诱导的合成化合物的循环,如多氯联苯(PCBs)的循环。某些循环中存在有储库,储库能使一种物质得以长时间保留或被隔离。

概要

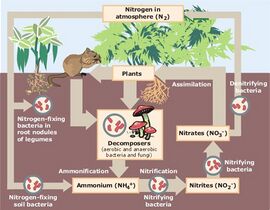

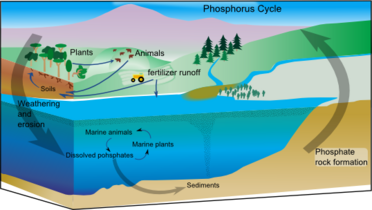

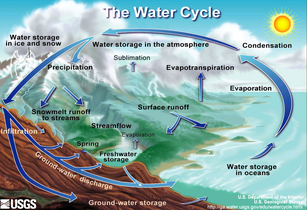

能量在生态系统中定向流动,以阳光(或化能自养生物的无机分子)的形式进入,并在营养级之间的众多转移过程中以热量的形式离开。然而,组成生物体的物质是被保存和循环利用的。与有机分子相关的六种最常见元素——碳、氮、氢、氧、磷和硫——以各种化学形式存在,并可能长期存在于大气、陆地、水体或者地表以下。地质过程,如风化、侵蚀、排水和大陆板块的俯冲,都在这种物质循环中发挥作用。由于地质学和化学在对于该过程的研究中起主要作用,无机物在生物体及其环境之间的循环便被称为生物地球化学循环。[1]

上述的六种元素以多种方式被生物体利用。氢和氧存在于水和有机分子中,这两种分子对于生命都是必不可少的。所有的有机分子都含有碳,而氮是核酸和蛋白质的重要成分。磷被用来制造核酸和构成生物膜的磷脂。硫对于蛋白质的三维形态至关重要。这些元素的循环是相互关联的。例如,水的流动对于硫和磷渗入河流并流入海洋是至关重要的。矿物质在生物和非生物成分间循环,并从一个生物体转移到另一个,从而在生物圈中进行循环。[2]

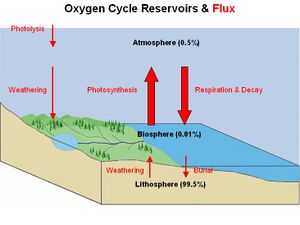

在生态系统中有很多生物地球化学循环过程作为系统的一部分运作,如水循环、碳循环、氮循环等等。生物体中所有的化学元素都是生物地球化学循环的一部分。除了作为生物体的一部分,这些化学元素还在生态系统的非生物因子中循环,如水(水圈),陆地(岩石圈)和/或空气(大气圈)。[3]

地球上的生命因素可以统称为生物圈。生态系统中生物体使用的所有营养物质,如碳、氮、氧、磷和硫,都是封闭系统中的一部分。因此,这些化学物质会被循环利用,而不是像在开放系统中那样不断丢失和补充。[3]

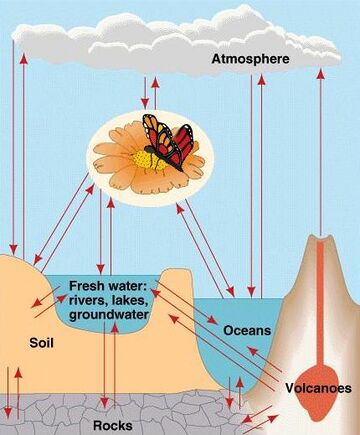

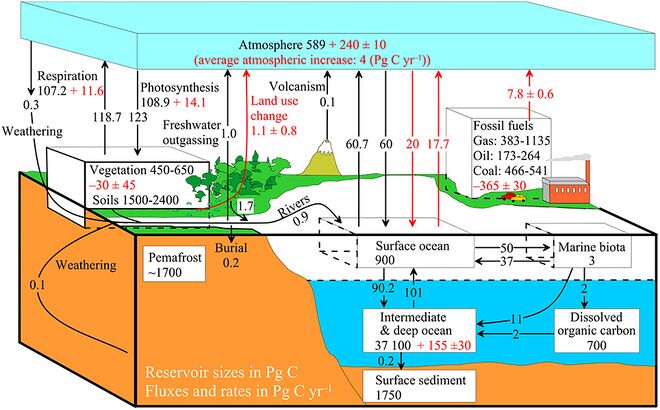

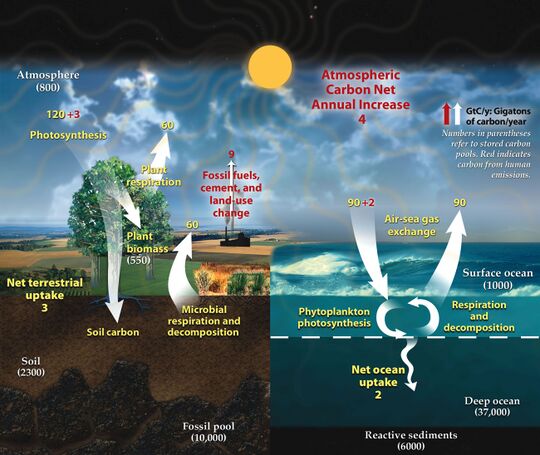

右图展示了一个广义的生物地球化学循环。生物圈的主要部分通过化学元素和化合物的流动相连接。在众多这样的循环中,生物群起了重要的作用。地球内部的物质通过火山喷发释放出来。大气与生物群和海洋之间进行化合物和元素的快速交换。相比之下,岩石、土壤和海洋的物质交换则通常缓慢一些。[4]

生态系统中的能量流动是一个开放系统。太阳不断以光能的形式给予地球能量,而这些能量最终以热量的形式在食物网的各营养级中被使用和散失。碳被用来制造碳水化合物、脂肪和蛋白质,它们是食物能量的主要来源。这些化合物被氧化,释放出二氧化碳,这些二氧化碳可以被植物捕获,制造出有机化合物。这种化学反应是由太阳的光能驱动的。

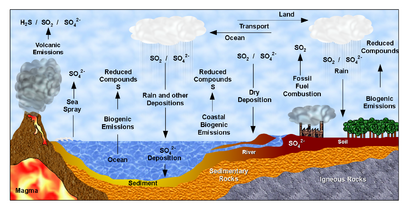

将碳与氢和氧结合成能源需要太阳光,但对于阳光无法达及的深海生态系统而言,其从硫中获取能量。热液喷口附近的硫化氢可以被巨型管虫等生物体利用。在硫循环中,硫可以作为能量源被永续循环利用。能量可以通过硫化物的氧化和还原来释放(例如硫被氧化为亚硫酸盐,再被氧化为硫酸盐)。

- Global carbon cycle.webp

人类活动引起的全球碳循环变化造成的影响令科学家们担忧。[5]

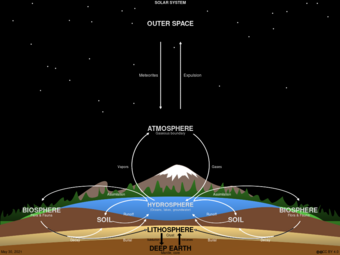

虽然地球源源不断地从太阳获取能量,但其化学成分基本上是固定的,额外的元素只是偶尔由陨石添加。因为这些化学成分不像能量那样能被补充,所有依赖于这些化学物质的过程都必须能被循环利用。这些循环包括有生命的生物圈和无生命的岩石圈、大气圈和水圈。

生物地球化学循环可以与地球化学循环形成对比。尽管两者的部分过程是重叠的,地球化学循环仅涉及地壳和地下储库。

储库

化学物质有时会在一个地方保存很长时间。这种地方被称作储库,包括诸如能长期储存碳的煤炭沉积。[6] 当化学物质只保留很短一段时间时,它们即被存放在交换池中。交换池的例子包括植物和动物。[6]

动植物利用碳来生产碳水化合物、脂肪和蛋白质,这些可之后被用于构建它们的内部结构或获取能量。植物和动物短暂地使用它们系统中的碳,随后将其释放到空气或周围的介质中。一般来说,储库是非生物因子,交换池是生物因子。与煤炭层相比,碳在动植物体内只保存相对较短的一段时间。一种化学物质在一个地方保留的时间被称为其停留时间或周转时间(也称为更新时间或退出时间)。[6]

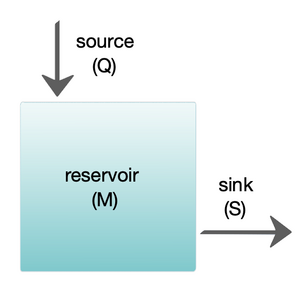

箱模型

箱模型被广泛用于生物地球化学系统建模。[7][8]箱模型是复杂系统的简化版本,将其简化为存放化学物质的箱(或储库),并由物质通量(流)进行连接。简单的箱模型含有少量属性不随时间变化的箱室,例如体积。这些箱室的行为被假定为是均匀混合的。这些模型经常被用于推导出解析公式以描述所涉及的化学物质的动力学和稳态丰度。

右图展示了一个基本的单箱模型。储库包含了所考虑的物质M的量,按照化学、物理或生物属性的定义。源Q是流入储库的物质通量,汇S是流出储库的物质通量。预算是影响储库内物质周转的源和汇的制衡。当Q = S,即源与汇处于平衡状态且不随时间变化时,储库处于稳态。[8]

停留时间或周转时间是物质在储库中停留的平均时间。如果储库处于稳态,其等于蓄满或排空储库所需的时间。因此,如果τ 是周转时间,那么 τ = M/S。[8]描述储库物质含量变化率的方程为

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dM}{dt} = Q - S = Q - \frac{M}{\tau} }[/math]

当两个或多个储库相连通时,可以认为物质在储库之间循环,且循环流动具有可预测的模式。[8]更复杂的多箱模型通常用数值方法求解。

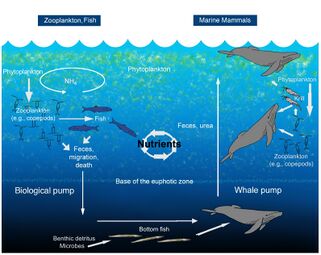

左上图显示了海洋碳流动的简化预算。它由三个相互连通的简单箱模型组成,一个是真光层,一个是海洋内部或深海,一个是海洋沉积物。在真光层,浮游植物每年净生产量约为50Pg。大约10Pg被输送到海洋内部,其余40Pg则被呼吸作用消耗。有机碳的降解发生在颗粒(海洋雪)在海洋内部沉降的过程中。只有2Pg的碳最终到达海底,其余的8Pg在深海中被呼吸作用消耗。在沉积物中,可供降解的时间尺度增加了一个数量级,导致90%的有机碳被降解,最终只有0.2PgC yr-1被埋藏并从生物圈转移到地圈。[9]

右上图显示了一个更复杂的模型,其中包含了许多相互作用的箱室。这里储库的质量代表碳储量,以Pg C为单位。碳交换通量以Pg C yr-1为单位,出现于大气和两个主要的碳汇,陆地和海洋之间。黑色的数字和箭头表示了1750年(工业革命之前)的碳库含量和交换通量的估计值。红色的箭头和对应的数字代表了2000-2009年人类活动导致的碳通量变化的年平均值。它们显示了1750年以来碳循环的变化情况。储库中的红色数字表示了自1750年至2011年,即工业革命开始以来人为碳的累积变化。[10][11][12]

隔室

生物圈

微生物驱动了地球系统中大部分的生物地球化学循环。[13][14]

大气圈

水圈

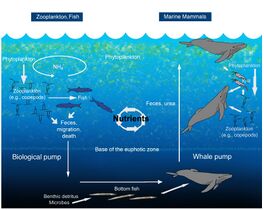

海洋覆盖了地球表面的70%以上,并且具有很强的异质性。海洋生产区和沿海生态系统只占海洋表面积的一小部分,但对微生物群落(占海洋生物量的90%)[15]所进行的全球生物地球化学循环有着巨大的影响。[16]近年来的工作主要集中在碳和常量营养元素(如氮、磷和硅酸盐)的循环上,对其它重要元素(如硫或微量元素)的研究较少,反映的相关的技术和后勤问题。这些海域以及构成其生态系统的分类群正日益受到人类活动的巨大压力,影响着海洋生物以及能量和营养物质的循环。[17][18][19]一个关键的例子是人为富营养化的影响,农业生产的径流导致沿海生态系统的氮和磷富集,使生产力大大提高并造成藻类大量繁殖,水体和海床脱氧,温室气体排放增加,[20]直接影响了区域和全球的氮循环和碳循环。然而,有机物从大陆流入沿海生态系统只是全球变化对微生物群落造成的一系列胁迫之一。气候变化还导致了冰冻圈的变化,冰川和永久冻土融化加剧了海洋分层,而不同生物群落中氧化还原状态的变化正以前所未有的速度迅速重塑微生物组合。[21][22][23][24][16]

因此,全球变化正在影响着关键过程,包括净初级生产力,CO2和N2固定,有机物呼吸/再矿化以及固定CO2的沉积和埋藏。[24]除此之外,海洋正在经历酸化过程,从前工业化时期到如今pH值变化了约0.1个单位,影响了碳酸盐和碳酸氢盐缓冲的化学过程。反过来,酸化主要通过对钙化类群的影响从而影响浮游生物群落。[25]还有证据表明,关键的中间挥发性产物的生产过程发生了变化,其中一些产物具有明显的温室效应(例如N2O和CH4,Breitburg在2018年的综述中所言。[22]由于全球温度升高,海洋分层和脱氧,在所谓的最低含氧区[26]或缺氧海洋区[27] 由于微生物的驱动导致大洋中25%-50%的氮损失到大气中)。其它对海洋自游生物有毒的产物,包括诸如H2S等硫的还原产物,对渔业和沿海水产养殖等海洋资源有负面影响。虽然全球变化加速,但人们对海洋生态系统复杂性的认识也在同步提高,尤其是微生物作为生态系统功能驱动因素的基本作用。[23][16]

岩石圈

快速和慢速循环

生物地球化学循环包括快速和慢速循环。快速循环在生物圈中运行,慢速循环在岩石中运行。快速循环或生物循环可以在数年内完成,将物质从大气转移到生物圈,再转移到大气。慢速或地质循环可能需要数百万年才能完成,使物质穿过岩石、土壤、海洋和大气在地壳中运移。[28]

快速的碳循环案例如左下图所示。这一循环包括环境和生物圈中生命体之间相对短期的地球化学过程。它包括碳在大气以及陆地和海洋生态系统、泥土和海底沉积物之间的运移。快速循环包括涉及光合作用的年周期和涉及植被生长和分解的年代周期。快速碳循环对人类活动的响应将决定气候变化许多更直接的影响。[29][30][31][32]

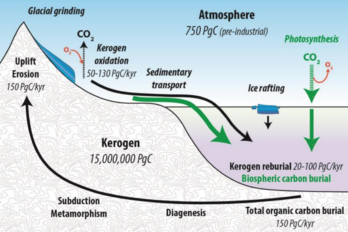

慢速循环如右上图所示,它涉及到岩石循环中的中长期地球化学过程。海洋和大气之间的交换可能需要几个世纪,而岩石的风化可能需要数百万年。海洋中的碳沉积在海底,在那里形成沉积岩并潜入地幔。造山运动使得这种地质碳回到地表。在地表,岩石被风化,碳通过脱气作用返回大气,通过河流返回海洋。其它的地质碳通过含钙离子热液的排放回到海洋。在一年中,有一千万至一亿吨的碳在这个缓慢的循环中移动。这包括火山将地质碳以二氧化碳的形式直接返还大气。然而,这还不足燃烧化石燃料排放到大气中的二氧化碳的百分之一。[28][29]

深层循环

陆地地下是地球上最大的碳储库,含有14-135Pg的碳和总生物量[34]的2-19%。[35]微生物在这种环境下驱动有机和无机化合物的转化,从而控制生物地球化学循环。目前对于地下微生物生态学的了解主要是基于16S核糖体RNA(rRNA)基因序列。最近的估计显示,公共数据库中小于8%的16S rRNA序列来自于地下生物,[36]且其中仅一小部分由基因组或分离物表示。因此,关于地下微生物代谢的可靠信息非常少。此外,关于地下生态系统中的生物体是如何在新陈代谢上互相关联的,我们知之甚少。一些基于栽培的同养群落研究[37][38][39]和对自然群落的小规模宏基因组学分析表明,[40][41][42]生物体通过代谢传递相联系:一个生物的氧化还原产物转移到另一生物。然而,还没有一个复杂的环境被彻底剖析,以解决支撑它们的代谢相互作用网络。这限制了生物地球化学模型捕捉碳和其他养分循环关键方面的能力。[43]新的方法,如基因组解析宏基因组学,可以在无需实验室分离的情况下为生物体提供一套全面的草图甚至是完整的基因组,[40][44][45]这种方法或许是理解生物地球化学过程的关键。[46]

一些案例

一些比较著名的生物地球化学循环如下:

许多生物地球化学循环正首次被研究。气候变化和人类影响正在极大地改变这些相对未知的循环的速度、强度和平衡,其中包括:

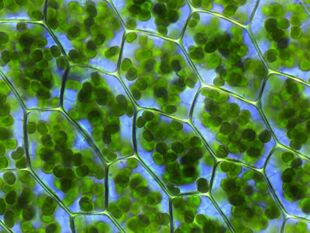

叶绿体在植物细胞和其他真核生物体中进行光合作用。

生物地球化学循环总是涉及活动平衡状态:在各隔室之间元素循环的平衡。然而,总体平衡可能涉及分布在全球尺度上的隔室。

由于生物地球化学循环描述了整个地球上物质的运动,其研究本质上是多学科的。碳循环可能与生态学和大气科学研究有关。[51]生化动力学也与地质学和土壤学领域有关。[52]

历史

另见

- 碳酸盐-硅酸盐循环

- 生态循环

- 大加速

- 氢循环

- 海洋生物地球化学循环

- 氧化还原梯度

参考文献

- ↑ Biogeochemical Cycles , OpenStax, 9 May 2019. 50px Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ↑ Fisher M. R. (Ed.) (2019) Environmental Biology, 3.2 Biogeochemical Cycles

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Biogeochemical Cycles". The Environmental Literacy Council. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Moses, M. (2012) Biogeochemical cycles. Encyclopedia of Earth.

- ↑ Avelar, S., van der Voort, T.S. and Eglinton, T.I. (2017) "Relevance of carbon stocks of marine sediments for national greenhouse gas inventories of maritime nations". Carbon balance and management, 12(1): 10.doi:10.1186/s13021-017-0077-x. 50px Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Baedke, Steve J.; Fichter, Lynn S. "Biogeochemical Cycles: Carbon Cycle". Supplimental Lecture Notes for Geol 398. James Madison University. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Sarmiento, J.L.; Toggweiler, J.R. (1984). "A new model for the role of the oceans in determining atmospheric P CO 2". Nature. 308 (5960): 621–24. Bibcode:1984Natur.308..621S. doi:10.1038/308621a0.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Bianchi, Thomas (2007) Biogeochemistry of Estuaries page 9, Oxford University Press. .

- ↑ 引用错误:无效

<ref>标签;未给name属性为Middelburg2019的引用提供文字 - ↑ Sarmiento, Jorge L.; Gruber, Nicolas (2002). "Sinks for Anthropogenic Carbon". Physics Today. 55 (8): 30–36. Bibcode:2002PhT....55h..30S. doi:10.1063/1.1510279.

- ↑ Chhabra, Abha (2013). "Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles". doi:10.13140/2.1.1081.8883.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Kandasamy, Selvaraj; Nagender Nath, Bejugam (2016). "Perspectives on the Terrestrial Organic Matter Transport and Burial along the Land-Deep Sea Continuum: Caveats in Our Understanding of Biogeochemical Processes and Future Needs". Frontiers in Marine Science. 3. doi:10.3389/fmars.2016.00259. 50px Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ↑ Falkowski, P. G.; Fenchel, T.; Delong, E. F. (2008). "The Microbial Engines That Drive Earth's Biogeochemical Cycles". Science. 320 (5879): 1034–1039. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1034F. doi:10.1126/science.1153213. PMID 18497287.

- ↑ Zakem, Emily J.; Polz, Martin F.; Follows, Michael J. (2020). "Redox-informed models of global biogeochemical cycles". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5680. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5680Z. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19454-w. PMC 7656242. PMID 33173062. 50px Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ↑ Alexander, Vera; Miloslavich, Patricia; Yarincik, Kristen (2011). "The Census of Marine Life—evolution of worldwide marine biodiversity research". Marine Biodiversity. 41 (4): 545–554. doi:10.1007/s12526-011-0084-1.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Murillo, Alejandro A.; Molina, Verónica; Salcedo-Castro, Julio; Harrod, Chris (2019). "Editorial: Marine Microbiome and Biogeochemical Cycles in Marine Productive Areas". Frontiers in Marine Science. 6. doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00657. 50px Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ↑ Galton, D. (1884) 10th Meeting: report of the royal commission on metropolitan sewage. J. Soc. Arts, 33: 290.

- ↑ Hasler, Arthur D. (1969). "Cultural Eutrophication is Reversible". BioScience. 19 (5): 425–431. doi:10.2307/1294478. JSTOR 1294478.

- ↑ Jickells, T. D.; Buitenhuis, E.; Altieri, K.; Baker, A. R.; Capone, D.; Duce, R. A.; Dentener, F.; Fennel, K.; Kanakidou, M.; Laroche, J.; Lee, K.; Liss, P.; Middelburg, J. J.; Moore, J. K.; Okin, G.; Oschlies, A.; Sarin, M.; Seitzinger, S.; Sharples, J.; Singh, A.; Suntharalingam, P.; Uematsu, M.; Zamora, L. M. (2017). "A reevaluation of the magnitude and impacts of anthropogenic atmospheric nitrogen inputs on the ocean". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 31 (2): 289. Bibcode:2017GBioC..31..289J. doi:10.1002/2016GB005586. hdl:1874/348077.

- ↑ Bouwman, A. F.; Van Drecht, G.; Knoop, J. M.; Beusen, A. H. W.; Meinardi, C. R. (2005). "Exploring changes in river nitrogen export to the world's oceans". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 19 (1). Bibcode:2005GBioC..19.1002B. doi:10.1029/2004GB002314.

- ↑ Altieri, Andrew H.; Gedan, Keryn B. (2015). "Climate change and dead zones". Global Change Biology. 21 (4): 1395–1406. Bibcode:2015GCBio..21.1395A. doi:10.1111/gcb.12754. PMID 25385668.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Breitburg, Denise; Levin, Lisa A.; Oschlies, Andreas; Grégoire, Marilaure; Chavez, Francisco P.; Conley, Daniel J.; Garçon, Véronique; Gilbert, Denis; Gutiérrez, Dimitri; Isensee, Kirsten; Jacinto, Gil S.; Limburg, Karin E.; Montes, Ivonne; Naqvi, S. W. A.; Pitcher, Grant C.; Rabalais, Nancy N.; Roman, Michael R.; Rose, Kenneth A.; Seibel, Brad A.; Telszewski, Maciej; Yasuhara, Moriaki; Zhang, Jing (2018). "Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters". Science. 359 (6371): eaam7240. Bibcode:2018Sci...359M7240B. doi:10.1126/science.aam7240. PMID 29301986.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Cavicchioli, Ricardo; et al. (2019). "Scientists' warning to humanity: Microorganisms and climate change". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 17 (9): 569–586. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0222-5. PMC 7136171. PMID 31213707.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Hutchins, David A.; Jansson, Janet K.; Remais, Justin V.; Rich, Virginia I.; Singh, Brajesh K.; Trivedi, Pankaj (2019). "Climate change microbiology — problems and perspectives". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 17 (6): 391–396. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0178-5. PMID 31092905.

- ↑ Stillman, Jonathon H.; Paganini, Adam W. (2015). "Biochemical adaptation to ocean acidification". Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (12): 1946–1955. doi:10.1242/jeb.115584. PMID 26085671.

- ↑ Bertagnolli, Anthony D.; Stewart, Frank J. (2018). "Microbial niches in marine oxygen minimum zones". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 16 (12): 723–729. doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0087-z. PMID 30250271.

- ↑ Ulloa, O.; Canfield, D. E.; Delong, E. F.; Letelier, R. M.; Stewart, F. J. (2012). "Microbial oceanography of anoxic oxygen minimum zones". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (40): 15996–16003. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10915996U. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205009109. PMC 3479542. PMID 22967509.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Libes, Susan M. (2015). Blue planet: The role of the oceans in nutrient cycling, maintain the atmosphere system, and modulating climate change In: Routledge Handbook of Ocean Resources and Management, Routledge, pages 89–107. .

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Bush, Martin J. (2020). Climate Change and Renewable Energy. pp. 109–141. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-15424-0_3. ISBN 978-3-030-15423-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=h_60DwAAQBAJ&q=%22Climate+Change+and+Renewable+Energy%22+%22The+Carbon+Cycle%22chapter+%3D+The+Carbon+Cycle&pg=PA109.

- ↑ Rothman, D. H. (2002). "Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels for the last 500 million years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (7): 4167–4171. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.4167R. doi:10.1073/pnas.022055499. PMC 123620. PMID 11904360.

- ↑ Carpinteri, Alberto; Niccolini, Gianni (2019). "Correlation between the Fluctuations in Worldwide Seismicity and Atmospheric Carbon Pollution". Sci. 1: 17. doi:10.3390/sci1010017. 50px Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- ↑ Rothman, Daniel (January 2015). "Earth's carbon cycle: A mathematical perspective". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society (in English). 52 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-2014-01471-5. hdl:1721.1/97900. ISSN 0273-0979. Archived from the original on 2021-11-22. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ Riebeek, Holli (16 June 2011). "The Carbon Cycle". Earth Observatory. NASA. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ↑ McMahon, Sean; Parnell, John (2014). "Weighing the deep continental biosphere". FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 87 (1): 113–120. doi:10.1111/1574-6941.12196. PMID 23991863.

- ↑ Kallmeyer, J.; Pockalny, R.; Adhikari, R. R.; Smith, D. C.; d'Hondt, S. (2012). "Global distribution of microbial abundance and biomass in subseafloor sediment". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (40): 16213–16216. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203849109. PMC 3479597. PMID 22927371.

- ↑ Schloss, Patrick D.; Girard, Rene A.; Martin, Thomas; Edwards, Joshua; Thrash, J. Cameron (2016). "Status of the Archaeal and Bacterial Census: An Update". mBio. 7 (3). doi:10.1128/mBio.00201-16. PMC 4895100. PMID 27190214.

- ↑ Abreu, Nicole A.; Taga, Michiko E. (2016). "Decoding molecular interactions in microbial communities". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 40 (5): 648–663. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuw019. PMC 5007284. PMID 27417261.

- ↑ Bosse, Magnus; Heuwieser, Alexander; Heinzel, Andreas; Nancucheo, Ivan; Melo Barbosa Dall'Agnol, Hivana; Lukas, Arno; Tzotzos, George; Mayer, Bernd (2015). "Interaction networks for identifying coupled molecular processes in microbial communities". BioData Mining. 8: 21. doi:10.1186/s13040-015-0054-4. PMC 4502522. PMID 26180552.

- ↑ Braker, Gesche; Dörsch, Peter; Bakken, Lars R. (2012). "Genetic characterization of denitrifier communities with contrasting intrinsic functional traits". FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 79 (2): 542–554. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01237.x. PMID 22092293.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Hug, Laura A.; Thomas, Brian C.; Sharon, Itai; Brown, Christopher T.; Sharma, Ritin; Hettich, Robert L.; Wilkins, Michael J.; Williams, Kenneth H.; Singh, Andrea; Banfield, Jillian F. (2016). "Critical biogeochemical functions in the subsurface are associated with bacteria from new phyla and little studied lineages". Environmental Microbiology. 18 (1): 159–173. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12930. PMID 26033198. Archived from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ McCarren, J.; Becker, J. W.; Repeta, D. J.; Shi, Y.; Young, C. R.; Malmstrom, R. R.; Chisholm, S. W.; Delong, E. F. (2010). "Microbial community transcriptomes reveal microbes and metabolic pathways associated with dissolved organic matter turnover in the sea". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (38): 16420–16427. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010732107. PMC 2944720. PMID 20807744.

- ↑ Embree, Mallory; Liu, Joanne K.; Al-Bassam, Mahmoud M.; Zengler, Karsten (2015). "Networks of energetic and metabolic interactions define dynamics in microbial communities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (50): 15450–15455. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11215450E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1506034112. PMC 4687543. PMID 26621749.

- ↑ Long, Philip E.; Williams, Kenneth H.; Hubbard, Susan S.; Banfield, Jillian F. (2016). "Microbial Metagenomics Reveals Climate-Relevant Subsurface Biogeochemical Processes". Trends in Microbiology. 24 (8): 600–610. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.04.006. PMID 27156744.

- ↑ Eren, A. Murat; Esen, Özcan C.; Quince, Christopher; Vineis, Joseph H.; Morrison, Hilary G.; Sogin, Mitchell L.; Delmont, Tom O. (2015). "Anvi'o: An advanced analysis and visualization platform for 'omics data". PeerJ. 3: e1319. doi:10.7717/peerj.1319. PMC 4614810. PMID 26500826.

- ↑ Alneberg, Johannes; Bjarnason, Brynjar Smári; De Bruijn, Ino; Schirmer, Melanie; Quick, Joshua; Ijaz, Umer Z.; Lahti, Leo; Loman, Nicholas J.; Andersson, Anders F.; Quince, Christopher (2014). "Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition". Nature Methods. 11 (11): 1144–1146. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3103. PMID 25218180.

- ↑ Anantharaman, Karthik; Brown, Christopher T.; Hug, Laura A.; Sharon, Itai; Castelle, Cindy J.; Probst, Alexander J.; Thomas, Brian C.; Singh, Andrea; Wilkins, Michael J.; Karaoz, Ulas; Brodie, Eoin L.; Williams, Kenneth H.; Hubbard, Susan S.; Banfield, Jillian F. (2016). "Thousands of microbial genomes shed light on interconnected biogeochemical processes in an aquifer system". Nature Communications. 7: 13219. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713219A. doi:10.1038/ncomms13219. PMC 5079060. PMID 27774985. 50px Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- ↑ "Mercury Cycling in the Environment". Wisconsin Water Science Center. United States Geological Survey. 10 January 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Organic contaminants that leave traces : sources, transport and fate. Ifremer. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9782759200139.

- ↑ Galy, Valier; Peucker-Ehrenbrink, Bernhard; Eglinton, Timothy (2015). "Global carbon export from the terrestrial biosphere controlled by erosion". Nature. 521 (7551): 204–207. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..204G. doi:10.1038/nature14400. PMID 25971513.

- ↑ Hedges, J.I; Oades, J.M (1997). "Comparative organic geochemistries of soils and marine sediments". Organic Geochemistry. 27 (7–8): 319–361. doi:10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00056-9.

- ↑ McGuire, 1A. D.; Lukina, N. V. (2007). "Biogeochemical cycles". Northern Eurasia earth science partnership initiative (NEESPI), Science plan overview. Global Planetary Change. 56. pp. 215–234. http://neespi.org/science/NEESPI_SP_chapters/SP_Chapter_3.2.pdf.

- ↑ "Distributed Active Archive Center for Biogeochemical Dynamics". daac.ornl.gov. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

进一步阅读

- Schink, Bernhard; "Microbes: Masters of the Global Element Cycles" pp 33–58. "Metals, Microbes and Minerals: The Biogeochemical Side of Life", pp xiv + 341. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin. DOI 10.1515/9783110589771-002

- Global biogeochemical cycles. London: Academic Press. 1993. ISBN 9780080954707.

- Exley, C (15 September 2003). "A biogeochemical cycle for aluminium?". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 97 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/S0162-0134(03)00274-5. PMID 14507454.

- Jacobson, Michael C.; Charlson, Robert J.; Rodhe, Henning; Orians, Gordon H. (2000). Earth system science from biogeochemical cycles to global change (2nd ed.). San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press. ISBN 9780080530642.

- Palmeri, Luca; Barausse, Alberto; Jorgensen, Sven Erik (2013). "12. Biogeochemical cycles". Ecological processes handbook. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781466558489.

编者推荐

本中文词条由张自在初步翻译,薄荷编辑,如有问题,欢迎在讨论页面留言。

本词条内容源自wikipedia及公开资料,遵守 CC3.0协议。