齐普夫定律 Zipf's law

齐普夫定律 Zipf's law是用数理统计公式表述的经验法则,由哈佛大学语言学家乔治·金斯利·齐夫 George Kingsley Zipf 于1949年发表,他揭示了在物理和社会科学中,各类型的数据研究所呈现出的图形,近似于齐普夫分布 Zipf distribution状态 。而齐普夫分布是一类相关的离散幂律概率分布。

| 参量 | [math]\displaystyle{ s \geq 0\, }[/math] (真实) [math]\displaystyle{ N \in \{1,2,3\ldots\} }[/math] (整数) |

| 支持 | [math]\displaystyle{ k \in \{1,2,\ldots,N\} }[/math] |

| pmf | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1/k^s}{H_{N,s}} }[/math] 其中 HN,s 是第 N个 谐波数 |

| CDF | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{H_{k,s}}{H_{N,s}} }[/math] |

| 意思 | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{H_{N,s-1}}{H_{N,s}} }[/math] |

| 模式 | [math]\displaystyle{ 1\, }[/math] |

| 方差 | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{H_{N,s-2}}{H_{N,s}}-\frac{H^2_{N,s-1}}{H^2_{N,s}} }[/math] |

| MGF | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{H_{N,s}}\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{e^{nt}}{n^s} }[/math] |

| 碳纤维 | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{H_{N,s}}\sum\limits_{n=1}^N \frac{e^{int}}{n^s} }[/math] |

| 熵 | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{s}{H_{N,s}}\sum\limits_{k=1}^N\frac{\ln(k)}{k^s} +\ln(H_{N,s}) }[/math] |

概览

齐普夫定律最初是根据计量语言学来制定的,一般表述为:在自然语言的语料库里,一个单词出现的频率与它在频率表里的排名成反比。则最频繁出现的单词的频率大约是第二个最频繁单词的两倍,是第三个最频繁单词的三倍,依此类推。这个定律被作为任何与幂定律概率分布有关的事物的参考。 例如:在布朗英文语料库中,单词 the 是最常出现的单词,占所有单词的近7%。根据齐普夫定律,排在第二位的 of 在单词中所占的比例略高于3.5%(共出现36,411次),其次为单词and(出现28,852次),仅前135个词汇就占了Brown语料库的一半。[1]

该定律以美国语言学家齐普夫命名,他致力于推广和阐释该定律,尽管他并没有声称自己是创始人。[2] 法国速记员让-巴蒂斯特·埃斯特鲁可能在齐普夫之前就注意到了这种规律。[3]1913年,德国物理学家费利克斯·奥尔巴赫也注意到了这一点。[4]

描述

齐普夫定律是一个实验定律,而非理论定律,可以在很多非语言学排名中被观察到,例如不同国家中城市的数量、公司的规模、收入排名等。但它的起因是一个争论的焦点。齐普夫定律很容易用点阵图观察,坐标分别为排名和频率的自然对数。比如,the用上述表述可以描述为[math]\displaystyle{ x = log(1), y = log }[/math]的点。如果所有的点接近一条直线,那么它就遵循齐普夫定律。[5]

而在1913年,费利克斯 · 奥尔巴赫首次注意到城市人口排名中的分布情况 根据实际经验,一组数据可以通过 Kolmogorov-Smirnov 检验来测试齐普夫定律是否适用于假设的幂律分布,然后将幂律分布的对数似然比与指数分布或对数正态分布进行比较。对城市进行齐普夫定律检验时,发现指数 [math]\displaystyle{ s = 1.07 }[/math]的拟合较好,达到预想规模。[6]

遵循该定律的现象

- 单词的出现频率:不仅适用于语料全体,也适用于单独的一篇文章

- 网页访问频率

- 城镇人口与城镇等级的关系

- 收入前3%的人的收入

- 地震震级

- 固体破碎时的碎片大小

理论回顾

齐普夫定律可以通过在对数图上绘制数据来观察得到。 例如,单词the(依据上方法)将表现在 [math]\displaystyle{ x=log (1) ,y=log }[/math](69971)中。 也可以根据频率或者倒数频率或者单词间隔来绘制倒数排序。如果图呈线性,那么数据符合齐普夫定律。

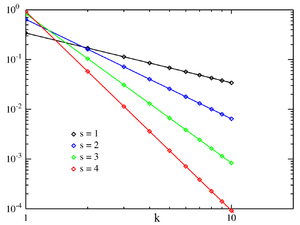

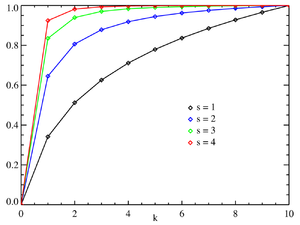

令:

- n:所考察元素的数量

- k:他们所代表的等级

- s:分布的指数值

然后齐普夫定律预测,在[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]元素总体中,等级[math]\displaystyle{ k,f (k; s,n) }[/math]元素的标准化频率是:

- [math]\displaystyle{ fksN=\frac{1/k^s}{\sum\limits_{n=1}^N (1/n^s)} }[/math]

如果给定频率的元素个数是幂律分布的随机变量,则齐普夫定律成立。[math]\displaystyle{ p(f) = \alpha f^{-1-1/s}. }[/math] [7]

有人说齐普夫定律的这种表述更适合于统计上的检验,并以这种方式在30,000多篇英文文本中进行了分析。 拟合优度测试的结果是,只有大约15% 的文本在统计学上符合齐普夫定律的表达。 而齐普夫定律定义的细微变化可以使这个百分比增加到接近50% 。[8]

在英语单词出现频率的例子中,[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]为英语单词的数量,如果我们使用典型的齐普夫定律进行测验,指数 [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] 为1。 [math]\displaystyle{ F (k; s,n) }[/math]将是第[math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]个最常见单词出现时间的分数。公式表达如下:[math]\displaystyle{ fksN=\frac{1}{k^sH_{Ns}} }[/math]

齐普夫定律最简单的例子如“[math]\displaystyle{ 1 / f }[/math] 函数” ,给定一组齐普夫分布频率,按照出现频率排序,出现频率的第二位数值是第一位频率数值的一半,第三位频率数值是第一位频率数值的[math]\displaystyle{ 1 / 3 }[/math],第[math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math]位频率数值是第一位频率数值的[math]\displaystyle{ 1 / n }[/math]。 但数值有可能不精确,因为统计条目必须出现整数次数; 同一个单词不能出现2.5次。 然而在相当广的范围内,很多自然现象都遵循齐普夫定律。

在人类语言中,词频有一个很明显的重尾分布,因此可以用一个 [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math]接近1的齐普夫分布来合理地建模。只要指数 [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] 大于1,这样的定律就有可能适用于无穷多个单词,

统计学解释

尽管齐普夫定律适用于所有语言,即使是像世界语(插入相关连接说明)这样的非自然语言,[9] 但其原理仍然没有得到很好的理解。 [10]然而,对随机产生的文本进行统计分析可以在某些方面解释这一现象。 Wentian Li表示,在一份文档中,每个字符都是从所有字母(加上一个空格字符)的均匀分布中随机选取的,不同长度的“单词”遵循齐普夫定律的宏观趋势,即可能性越大的单词越短,出现概率越大。[11] 维托尔德 · 贝列维奇在《语言分布的统计规律》中给出了一个数学推导。 他取了一大类表现良好的统计分布(不仅仅是正态分布) ,并用把他们排列名次。 然后他把每个表达式展开成一个泰勒级数。 在每一种情况下,贝列维奇都得到了显著的成果,即级数的一阶截断导出了齐普夫定律。 此外,对泰勒级数的二阶截断导出了曼德布洛特定律。[12]

最小努力原则是另一种来解释齐普夫定律的途径: 齐普夫本人提出,使用特定语言的说话者和接收者都不想仅仅为了理解而付出超额努力,从而导致努力的程度大致平等分配的过程产生了我们所观察到的齐普夫分布。[13] [14]

类似地,偏好依附(直观的看到“富人越来越富”或“成功孕育成功”)产生了Yule-Simon 分布,这已被证明比齐普夫定律更适合语言中的词频与排名`人口与城市排名研究。[15]

它最初是由 Yule 用来阐明种群与等级的关系,并由 Simon 用来阐释城市的关系。

相关定律

一般地,齐普夫定律指的是“等级数据”的频率分布,其中排名第[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] 的条目的相对频率由 Zeta 分布来表达为[math]\displaystyle{ 1 / (nsζ(s)) }[/math] ,其中参数 [math]\displaystyle{ s1 }[/math]指的是这个概率分布群的部分。事实上,由于概率分布有时被称为“定律” ,齐普夫定律有时就是“ Zeta分布”的同义词。 这种分布有时被称为Zipf分布。

对齐普夫定律的一个推广是 Zipf-Mandelbrot 定律,由本华·曼德博提出,其频率为:

- [math]\displaystyle{ fkNqs=\frac{[\text{constant}]}{(k+q)^s}.\, }[/math]

齐普夫分布可以通过变量的变化从帕累托分布中得到。[16] 有时也被称为离散帕累托分布,因为它类似于连续帕累托分布,就像离散型均匀分布类似于连续型均匀分布一样。

本福德定律是 齐普夫定律的一种特殊的有界情形,这两个定律之间的联系,[17] [18]就在于它们都起源于统计物理和临界现象的尺度不变函数关系(尺度不变特征)。在本福德定律中,概率的比率是不固定的。[17] [19] 满足齐普夫定律的前位数 [math]\displaystyle{ s = 1 }[/math]同样也满足本福特定律。

| [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] | 本福德定律: [math]\displaystyle{ P(n) = }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \log_{10}(n+1)-\log_{10}(n) }[/math] |

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\log(P(n)/P(n-1))}{\log(n/(n-1))} }[/math] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.30103000 | |

| 2 | 0.17609126 | −0.7735840 |

| 3 | 0.12493874 | −0.8463832 |

| 4 | 0.09691001 | −0.8830605 |

| 5 | 0.07918125 | −0.9054412 |

| 6 | 0.06694679 | −0.9205788 |

| 7 | 0.05799195 | −0.9315169 |

| 8 | 0.05115252 | −0.9397966 |

| 9 | 0.04575749 | −0.9462848 |

应用

在信息论中,概率的符号(事件,信号)[math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] 包含[math]\displaystyle{ \log_2(1/p) }[/math] 比特的信息。因此,自然数的齐普夫定律:[math]\displaystyle{ \Pr(x) \approx 1/x }[/math]等价于数字 [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] 包含 [math]\displaystyle{ \log_2(x) }[/math]信息点。从概率符号中添加信息 [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] 转化为已经存储在自然数中的信息 [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], 我们需要 [math]\displaystyle{ x' }[/math] 这样比如 [math]\displaystyle{ \log_2(x') \approx \log_2(x) + \log_2(1/p) }[/math], 或者相等于 [math]\displaystyle{ x' \approx x/p }[/math].例如,在标准二进制系统中 [math]\displaystyle{ x' = 2x + s }[/math], 对于其是最优的 [math]\displaystyle{ \Pr(s=0) = \Pr(s=1) = 1/2 }[/math] 可能分布. 使用 [math]\displaystyle{ x' \approx x/p }[/math] 一般概率分布的规则是非对称数字系统系列熵编码方法的基础,数据压缩系列的状态分布也受齐普夫定律支配。

齐普夫定律也被用于从可比较的语料库中提取文本的平行片段.[20]

[21]

其他参阅

- 简洁定律

- Heaps law

- Menzerath–Altmann定律

- 布拉福定律

- 本福特定律

- 人口引力

- 词频表

- 吉布拉定律

- 罕用语Hapax legomenon

- 洛伦兹曲线

- 洛特卡定律

- 帕累托分布

- 帕累托原则, a.k.a. the "80–20 rule"

- 最小努力原则

- 普赖斯定律

- 排级规模分布

- 金效应

- Stigler's law of eponymy

- 1% 规律(互联网文化)

参考文献

- ↑ Fagan, Ramazan, David E. A "An introduction to textual econometrics", "For example, in the Brown Corpus, consisting of over one million words, half of the word volume consists of repeated uses of only 135 words.".Handbook of Empirical Economics and Finance.139.(133--153)

- ↑ David M. W. Powers (1998) Applications and Explanations of Zipf’s Law.

- ↑ [1] Christopher D. Manning, Hinrich Schütze Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing, MIT Press (1999), p. 24

- ↑ Auerbach F. (1913) Das Gesetz der Bevölkerungskonzentration. Petermann’s Geographische Mitteilungen 59, 74–76

- ↑ David M. W. Powers (1998) Applications and Explanations of Zipf’s Law.

- ↑ Clauset, A., Shalizi, C. R., & Newman, M. E. J. (2009). Power-Law Distributions in Empirical Data. SIAM Review, 51(4), 661–703. doi:10.1137/070710111

- ↑ Adamic, Lada A. (2000) "Zipf, Power-laws, and Pareto - a ranking tutorial".(2007)

- ↑ Moreno-Sánchez, I, Font-Clos, F, A (2016) "Large-Scale Analysis of Zipf's Law in English Texts".PLOS One, arXiv:1509.04486. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147073. PMC 4723055. PMID 26800025..11.

- ↑ ZIPF'S LAW (PDF (2006) INVESTIGATING ESPERANTO'S STATISTICAL PROPORTIONS RELATIVE TO OTHER LANGUAGES USING NEURAL NETWORKS, ), Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016.Bill Manaris; Luca Pellicoro; George Pothering; Harland Hodges (13 February, Artificial Intelligence and Applications.(102--108)

- ↑ Léon Brillouin, La science et la théorie de l'information, 1959, réédité en 1988, traduction anglaise rééditée en 2004

- ↑ Li, Wentian (1992) "Random Texts Exhibit Zipf's-Law-Like Word Frequency Distribution".IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.164.8422. doi:10.1109/18.38.(1842--1845)

- ↑ Neumann, Peter G."Statistical metalinguistics and Zipf/Pareto/Mandelbrot", SRI International Computer Science Laboratory, accessed and archived 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Sole, Ramon Ferrer i Cancho (2003) "Least effort and the origins of scaling in human language".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, PMC 298679. PMID 12540826. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01..100, 10.(788--791)

- ↑ Lin, Bian, Chunhua (2014) "Scaling laws in human speech, decreasing emergence of new words and a generalized model".arXiv:1412.4846 [cs.CL].

- ↑ Vitanov, Nikolay, K., Ausloos, Chunhua (2015) "Test of two hypotheses explaining the size of populations in a system of cities".Journal of Applied Statistics.42, 1506, 10, 1047744.(2686--2693)

- ↑ N. L. Johnson; S. Kotz; A. W. Kemp (1992). Univariate Discrete Distributions (second ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 978-0-471-54897-3., p. 466.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Johan Gerard van der Galien (2003-11-08). "Factorial randomness: the Laws of Benford and Zipf with respect to the first digit distribution of the factor sequence from the natural numbers". Archived from the original on 2007-03-05. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ Ali Eftekhari (2006) Fractal geometry of texts. Journal of Quantitative Linguistic 13(2-3): 177–193.

- ↑ L. Pietronero, E. Tosatti, V. Tosatti, A. Vespignani (2001) Explaining the uneven distribution of numbers in nature: The laws of Benford and Zipf. Physica A 293: 297–304.

- ↑ Mohammadi, Mehdi (2016) "Parallel Document Identification using Zipf's Law" (PDF), Archived (PDF) from the original on.Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop on Building and Using Comparable Corpora. LREC 2016.03.(21--25)

- ↑ Gabaix, Xavier (August 1999). "Zipf's Law for Cities: An Explanation" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 114 (3): 739–67. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.180.4097. doi:10.1162/003355399556133. ISSN 0033-5533

编者推荐

城市人口分布有何规律?

国外城市规模分布研究进展及理论前瞻——基于齐普夫定律的分析

信息计量学(五) 第五讲 文献信息词频分布规律——齐普夫定律

本中文词条由厚朴参与编译,苏格兰审校,许许编辑,欢迎在讨论页面留言。

本词条内容源自wikipedia及公开资料,遵守 CC3.0协议。