“自组织”的版本间的差异

(→人类社会) |

(→交通流) |

||

| 第106行: | 第106行: | ||

===交通流=== | ===交通流=== | ||

| − | |||

交通流中驾驶员的自组织行为几乎决定了交通的所有时空行为,例如高速公路瓶颈处的交通故障,高速公路通行能力以及交通拥堵的出现。在1996–2002年,鲍里斯·克纳 Boris Kerner 的三相交通理论解释了这些复杂的自组织效应。<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Kerner | first1 = Boris S. | year = 1998 | title = Experimental Features of Self-Organization in Traffic Flow | journal = Physical Review Letters | volume = 81| issue = 17 | pages = 3797–3800| doi=10.1103/physrevlett.81.3797 | bibcode=1998PhRvL..81.3797K}}</ref> | 交通流中驾驶员的自组织行为几乎决定了交通的所有时空行为,例如高速公路瓶颈处的交通故障,高速公路通行能力以及交通拥堵的出现。在1996–2002年,鲍里斯·克纳 Boris Kerner 的三相交通理论解释了这些复杂的自组织效应。<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Kerner | first1 = Boris S. | year = 1998 | title = Experimental Features of Self-Organization in Traffic Flow | journal = Physical Review Letters | volume = 81| issue = 17 | pages = 3797–3800| doi=10.1103/physrevlett.81.3797 | bibcode=1998PhRvL..81.3797K}}</ref> | ||

2020年5月12日 (二) 13:26的版本

自组织 Self-organization, 在社会科学中 也被称为自发秩序,是指一种起源于初始无序系统的部分元素之间的局部相互作用、所产生出某种形式的整体秩序的过程。当有足够的能量可用时,该过程可以是自发的,不需要任何外部个体 agent进行控制。它通常是由看似随机的波动触发,并由正反馈放大。最终形成的自组织是完全分散的,分布在系统的所有组件中。因此,自组织通常是健壮的,能够生存下来或者自我修复严重的干扰。混沌理论讨论的自组织,如同无序、不可预测的大海中的确定性孤岛。

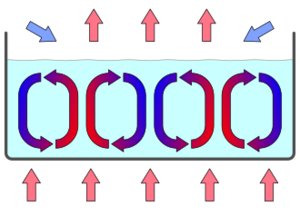

自组织发生在物理,化学,生物,机器人和认知系统等许多领域。自组织的例子包括结晶,流体的热对流,化学振荡,动物种群,神经回路。

自组织是在非均衡 Non-equilibrium 过程的物理学和化学反应中被发现的,[2]通常将其描述为自组装 Self-assembly 。在生物学中,从分子到生态系统,这一概念已被证明是有效的。[3]在自然科学和社会科学 例如经济学或人类学 的许多其他学科的文献中也出现了自组织行为的引证。在诸如元胞自动机 Cellular automata 这样的数学系统中也观察到了自组织。[4]自组织是与涌现 Emergence 概念相关的一个例子。[5]

自组织依赖于四个基本要素:[6]

- 强烈的动态非线性,通常但不必然涉及正反馈和负反馈

- 探索与开发的平衡

- 多重互动

- 能量的可用性 以克服熵增 Entropy 或无序的自然趋势

原理

控制论专家威廉·罗斯·阿什比 W. Ross Ashby 在1947年提出了自组织 Self-organization 的初始原理,[7][8]它指出任何确定性动力系统都会自动演变成一个均衡状态,这种均衡状态可以描述为一个在盆地周围环绕状态的吸引子 Attractor 。一旦到达那里,系统的进一步演化就被约束以保持在吸引子中。这种约束代表了其组成元素或子系统之间相互依赖或协调的某种形式。用阿什比的话来说,每个子系统都适应了所有其他子系统形成的环境。[7]

控制论专家海因茨·冯·福斯特 Heinz von Foerster 于1960年提出了“ 从噪声中获得秩序 Order from noise ” 的原理。[9] 该原理指出,自组织是由随机扰动 “噪声” 促进的,该随机扰动使系统在其状态空间中探索各种状态。这增加了系统到达“强”或“深”吸引子池中的机会,然后系统会迅速进入吸引子本身。生物物理学家亨利·阿特兰 Henri Atlan 通过提出“ 噪声带来的复杂性 Complexity from noise,法语 le principe de complexité par le bruit ” 原理发展了这一概念,[10][11] 该原理首见于1972年出版的《L'organisation biologique et lathéoriede l'information》,[12] 然后是1979年出版的《Entre le cristal et lafumée》。[13] or "order out of chaos".[14]热力学家伊利亚·普里戈吉因 Ilya Prigogine 提出了类似的原则,即“波动带来有序 Order through fluctuations ”[15] 或“混乱带来有序 Order out of chaos ”[16]。它也应用在用于解决问题和机器学习的模拟退火方法中。[17]

历史演变

系统动力演化可以导致其组织增加的想法由来已久。像德谟克里特 Democritus 和卢克雷修斯 Lucretius 之类的古代原子论者认为,一种有计划的智能对于在自然界中创造秩序是不必要的,他们认为,只要有足够的时间、空间和物质,秩序就会自动产生。[18]

哲学家勒内·笛卡尔 RenéDescartes 在其1637 年《方法论》的第五部分中假设性提出了自我组织 Selft-organization 的概念。他在未发表的作品“世界”中详细阐述了这个想法。

依曼纽尔·康德 Immanuel Kant 在他的1790年《审判批判》中使用了“自组织化 Selft-onganizing”一词,他认为只有存在这样的实体——其各个部分或“器官 Organs ”同时是终点和手段时——才是有意义的概念。这样的器官系统一定能够像拥有自己的思想一样行事,也就是说,它能够自我支配。.[19]

“在这样的天然产物中,其每一个部件都因其他剩余部件的存在而存在,也可以说它的存在是为了其他部件和整个整体,这是作为一种手段,或器官……该部件必须是可以产生其他部件的器官——因此每个部件都会相互产生其他部件……只有在这些条件和关系下,这样的产物才能成为一个系统的和自组织的存在,而且因此才能被称为一个物理结束。”[19]

萨迪·卡诺 Sadi Carnot,1796-1832 和鲁道夫·克劳修斯 Rudolf Clausius,1822-1888 在19世纪发现了热力学第二定律。它指出:总的熵,有时被理解为无序,在一个孤立的系统中总会随着时间而增加。这意味着,如果没有外部联系降低系统中其他部位的有序 Order 例如,通过消耗电池的低熵能量来扩散高熵热 ,那么系统无法自发地增加有序。[20][21]

18世纪的思想家试图理解“形式的普遍定律 Universal laws of form ”,以解释观察到的生物体形式。这个想法与拉马克主义 Lamarckism 联系在一起,并声名狼藉,直到20世纪初 D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson 1860–1948 试图复兴它。[22]

精神病学家和工程师 Ashby 于1947年向当代科学引入了“自组织 Self-organizing”一词。[7] 控制论学者 Heinz von Foerster,戈登·帕斯克 Gordon Pask ,斯塔福德·比尔 Stafford Beer 采纳了这一概念,Heinz von Foerster于1960年6月在伊利诺伊大学阿勒顿公园组织了一次有关“自组织原理 The Principles of Self-Organization ”的会议,该会议引发了一系列关于自组织系统的会议。[23] 诺伯特·维纳 Norbert Wiener在他的《控制论》第二版中提出了这个想法:《动物与机器中的控制与通讯》 1961 。

自组织 Self-organization 与60年代的一般系统理论相关,但是直到物理学家 Hermann Haken等人和复杂系统的研究者从更大范围采纳了这一概念才在科学文献中变得司空见惯起来,这些范围包括宇宙学家埃里希•詹茨 Erich Jantsch ,耗散系统的化学,具备系统思维 兴起于1980年代圣塔菲学院 Santa Fe Institute和1990年代复杂适应系统 的自创生 Autopoiesis 机制的生物学和社会学领域,以及如今受根茎网络理论 Rhizomatic network theory 深刻影响而出现的颠覆性技术。[24]

在2008-2009年,引导式自组织 Guided self-organization 的概念开始形成。这种方法旨在针对特定目的调整自组织,以便动态系统可以达到特定的吸引子或结果。这种调整通过限制系统组件之间的局部相互作用,而不是依靠一种明确的控制机制或全局设计蓝图,来限制复杂系统中的自组织过程。通过将任务无关的全局目标与任务相关的对局部相互作用的约束相结合,可以实现预期的结果,例如增加由此带来的内部结构和/或功能。[25][26]

按领域

物理

物理学中的自组织现象包括相变 Phase transitions 和自发对称性破缺 Spontaneous symmetry breaking ,例如自发磁化 Spontaneous magnetization ,经典物理学中的晶体生长,激光,[27] 超导和量子物理学的玻色-爱因斯坦凝聚 Bose–Einstein condensation 。它在动力学系统,摩擦学,自旋泡沫系统 Spin foam systems 和环量子引力 Loop quantum gravity [28] 的自组织临界 Self-organized criticality 中被发现,也在河流盆地和三角洲,枝晶凝固 Dendritic solidification (如雪花) 和湍流结构 Turbulent structure 中被发现。[3][4]

化学

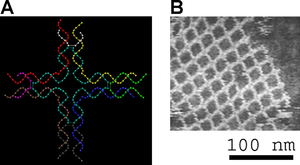

化学中的自组织包括分子自组装 Molecular self-assembly,[29] 反应扩散系统 Reaction–diffusion systems 和振荡反应 Oscillating reactions,[30] 自催化网络 Autocatalytic networks,液晶 Liquid crystals,[31] 网格络合物 Ggrid complexes,胶质晶体 Colloidal crystals,自组装单分子层 Self-assembled monolayers,[32][33]胶束 Micelles,嵌段共聚物的微相分离 Microphase separation of block copolymers 和Langmuir-Blodgett膜 Langmuir–Blodgett films。[34]

生物

在生物学中[35],从蛋白质和其它生物大分子的自发折叠 Spontaneous folding,磷脂双分子层 Lipid bilayer 的形成,发育生物学的图案形成 Pattern formation和形态发生 Morphogenesis,人体运动的协调,群居昆虫 如蜜蜂,蚂蚁,白蚁[36] 和哺乳动物的社会行为,到鸟类和鱼类的群集行为 Flocking behaviour,都可以观察到自组织现象。[37]

数学生物学家斯图尔特·考夫曼 Stuart Kauffman 和其他结构主义者认为,自组织可能与自然选择在进化生物学的三个领域中共同发挥作用,即种群动力学 Population dynamics,分子进化 Molecular evolution 和形态发生 Morphogenesis。但是,这种假设没有考虑能量在驱动细胞中生化反应中的重要作用。任何细胞中的反应系统都是自催化 Self-catalyzing的,但不是简单的自组织,因为它们是依赖于持续能量输入的热力学开放系统。自组织不是自然选择的替代方法,但是它限制了进化可以做什么,并提供了诸如膜的自组装之类的机制,以便进化利用这种机制。[38][39] Self-organization is not an alternative to natural selection, but it constrains what evolution can do and provides mechanisms such as the self-assembly of membranes which evolution then exploits.[40]

计算机科学

来自数学和计算机科学的现象,例如元胞自动机 Cellular automata,随机图 Random graphs,以及进化计算 Evolutionary computation 和人工生命 Artificial life 的某些实例,都表现出了自组织的特征。在群体机器人 Swarm robotics 中,自组织被用来产生涌现行为 Emergent behavior。尤其是随机图理论作为复杂系统的一般原理,已被用作自组织的正当理由。在多主体系统领域,理解如何设计一个能够表现出自组织行为的系统是一个活跃的研究领域。[41]优化算法也可以认为是自组织化 Self-organizing的,因为它们旨在找到问题的最优解。如果将这个解视为迭代系统的一个状态,则最优解是系统选定的收敛结构。[42][43] 自组织网络包括 小世界网络 Small-world networks [44] 和 无标度网络 Scale-free networks。它们来自自下而上的相互作用,这与组织内部的自上而下的层次网络不同,后者不是自组织的。[45] 有人认为云计算系统本质上也是自组织的,[46] 但尽管它们具有一定的自治性,它们并不是自我管理的,因为它们的目标不是降低自身的复杂性。[47][48]

控制论

诺伯特·维纳认为黑盒的自动串行识别 Automatic serial identification 及其随后的复制 Reproduction 作为控制论中的自组织。[49]维纳所称的锁相 Phase locking 或“频率吸引 Attraction of frequencies”的重要性在他的《控制论——动物与机器中的控制与通信》第二版中进行了讨论。[50] 埃里克·德雷克斯勒 K. Eric Drexler 将自我复制 Self-replication 视为纳米和通用组装 universal assembly 的关键步骤。[51]相比之下,当 Ross Ashby 的同态调节器——四个同时连通的检流计——受到干扰时,会收敛于许多可能的稳定状态之一。Ross Ashby使用各种状态计数方法来描述稳定状态,并推导出“良好调节器 Good Regulator ” 定理,[52] 该定理要求内部模型具有自组织的持久性和稳定性。例如,奈奎斯特稳定性标准 Nyquist stability criterion。沃伦·麦卡洛克 Warren McCulloch 提出的“潜在命令冗余 Redundancy of Potential Command”,是大脑和人类神经系统组织的特征,也是自组织的必要条件。Heinz von Foerster提出了“冗余度 Redundancy”,[math]\displaystyle{ R=1-H /H_{max} }[/math],其中[math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math]是熵。[53][54] 本质上,这表明未使用的潜在通信带宽是对自组织的一种度量。

1970年代,Stafford Beer 认为自组织对于持久的生命系统的自治是必要的。他将活性系统模型 viable system model应用于管理。它由五个部分组成:

- 监视生存过程的表现

- 通过规则的递归应用进行管理

- 稳态操作控制

- 开发

- 使得在环境干扰下依然可维持身份

通过警报“algedonic loop”反馈来优选焦点:这种反馈是一种对相对于标准功能表现不足或超出表现所产生的疼痛和愉悦的敏感性。[55]

在1990年代,Gordon Pask 辩称,von Foerster 的H和Hmax不是独立的,而是通过可数的无限递归并发自旋过程 Countably infinite recursive concurrent spin processes 相互作用的,[56] 他称之为概念。他严格定义了“建立关系的程序 A procedure to bring about a relation”这一概念,[57] 使得他的定理“相似概念排斥,不同概念吸引 Like concepts repel, unlike concepts attract” ,[58] 以得出一种通用的、基于自旋的自组织原理。他的原则是一项排除原则,“ 非二重性 There are No Doppelgangers ”意味着没有两个概念完全相同。经过足够的时间后,所有概念都吸引并合并成为粉红噪音 Pink noise。[59][56]该理论应用于可以产生持久、连贯产品的所有组织封闭 Organizationally closed 或体内平衡 Homeostatic 的过程,这些产品会不断发展,学习和适应。

人类社会

社会动物的自组织行为和简单数学结构的自组织现象,都表明在人类社会中应该存在自组织。自组织的迹象通常是自组织物理系统所体现出的统计属性。社会学,经济学,行为金融学和人类学中存在很多这样的例子,比如临界质量 Critical mass,羊群效应 Herd behaviour,集体思维 Groupthink 等。[60]

在社会理论中,尼古拉斯·卢曼 Niklas Luhmann 1984 引入了自我指涉 Self-referentiality的概念作为自组织理论的社会学应用。对于卢曼而言,社会系统的要素是自我再生产 Self-producing 的交流,即交流产生进一步的交流,因此,只要存在不断变化的交流,社会系统就可以自我复制。对于卢曼而言,人类就是系统环境中的传感器。卢曼通过功能分析 Functional analyses 和系统理论发展出一套关于社会及其子系统的进化论。[61]

在经济学中,市场经济有时被认为是自组织的 Self-organizing。保罗·克鲁格曼 Paul Krugman 在他的著作《自组织经济 》(The Self Organizing Economy) 中阐述了市场自组织在商业周期中的作用。弗里德里希·哈耶克 Friedrich Hayek 创造了术语“ 耦合秩序 catallaxy” ,以描述一种“自愿合作的自组织系统 Self-organizing system of voluntary co-operation”,这与自由市场经济中的自发秩序有关。新古典经济学家认为,加强中央计划通常会使自组织的经济体系效率降低。从另一个角度来看,经济学家认为市场失灵如此明显以至于自组织产生了不良结果,因此国家应指导生产和定价。大多数经济学家都采取中间立场,并建议将市场经济和计划经济 Command economy 的特征混合在一起 有时称为混合经济 Mixed economy 。当应用在经济学领域时,自组织的概念很容易变成一种意识形态上的渗透。[62][63]

学习领域

使他人“学习如何学习”[64] 通常是指教导他们如何服从于被教导。自组织学习 Self-organised learning, SOL [65][66][67] 否认“专家最了解”或存在“最佳方法”,[68][69][70] 反而坚持认为“个体层面显著的、相关的和可行意义的建构”,[71] 应由学习者进行体验性尝试。[72] 这可能是协作完成的,而且个人收获更大。[73][74] 它被视为一生的过程,并不受限于特定的学习环境 家庭,学校,大学 ,也不受限于父母或教授等权威机构的控制。[75] 它需要通过学习者的亲身经历去尝试、并且不断去修正。[76] 它也不必受限于意识或语言。[77]弗里特霍夫·卡普拉 Fritjof Capra 声称,这自组织学习,在心理学和教育中鲜为人知。[78] 它可能与控制论有关,[57] or to systems theory.[79]因为它涉及负反馈控制回路 Negative feedback control loop,或者与系统理论有关。它可以作为学习谈话或对话在学习者之间或一个人进行。[80][81]

交通流

交通流中驾驶员的自组织行为几乎决定了交通的所有时空行为,例如高速公路瓶颈处的交通故障,高速公路通行能力以及交通拥堵的出现。在1996–2002年,鲍里斯·克纳 Boris Kerner 的三相交通理论解释了这些复杂的自组织效应。[82]

语言学

随着个体和群体行为与生物进化相互作用,秩序在语言的进化中自发出现。[83]

研究基金

自组织拨款 Self-organized funding allocation,SOFA 是为科学研究分配资金的一种方法。在这个系统中,每个研究人员都被分配了相等数量的资金,并且被要求匿名分配他们一部分资金用于其他人的研究。SOFA的支持者认为,这将导致与目前的拨款系统相似的资金分配,但开销却更少。2016年,SOFA的测试试点在荷兰开始。[84] In 2016, a test pilot of SOFA began in the Netherlands.[85]

参考文献

- ↑ Betzler, S. B.; Wisnet, A.; Breitbach, B.; Mitterbauer, C.; Weickert, J.; Schmidt-Mende, L.; Scheu, C. (2014). "Template-free synthesis of novel, highly-ordered 3D hierarchical Nb3O7(OH) superstructures with semiconductive and photoactive properties" (PDF). Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2 (30): 12005. doi:10.1039/C4TA02202E.

- ↑ Glansdorff, P., Prigogine, I. (1971). Thermodynamic Theory of Structure, Stability and Fluctuations, Wiley-Interscience, London.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Compare: Camazine, Scott (2003). Self-organization in Biological Systems. Princeton studies in complexity (reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691116242. https://books.google.com/books?id=zMgyNN6Ufj0C.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ilachinski, Andrew (2001). Cellular Automata: A Discrete Universe. World Scientific. p. 247. ISBN 9789812381835. https://books.google.com/books?id=3Hx2lx_pEF8C. "We have already seen ample evidence for what is arguably the single most impressive general property of CA, namely their capacity for self-organization"

- ↑ Feltz, Bernard (2006). Self-organization and Emergence in Life Sciences. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-402-03916-4.

- ↑ Bonabeau, Eric; Dorigo, Marco; Theraulaz, Guy (1999). Swarm intelligence: from natural to artificial systems. OUP USA. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-19-513159-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=PvTDhzqMr7cC.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ashby, W. R. (1947). "Principles of the Self-Organizing Dynamic System". The Journal of General Psychology. 37 (2): 125–28. doi:10.1080/00221309.1947.9918144. PMID 20270223.

- ↑ Ashby, W. R. (1962). "Principles of the self-organizing system", pp. 255–78 in Principles of Self-Organization. Heinz von Foerster and George W. Zopf, Jr. (eds.) U.S. Office of Naval Research.

- ↑ Von Foerster, H. (1960). "On self-organizing systems and their environments", pp. 31–50 in Self-organizing systems. M.C. Yovits and S. Cameron (eds.), Pergamon Press, London

- ↑ See occurrences on Google Books.

- ↑ François, Charles, ed. (2011) [1997]. International Encyclopedia of Systems and Cybernetics (2nd ed.). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 107. ISBN 978-3-1109-6801-9.

- ↑ [1].

- ↑ Nicolis, G. and Prigogine, I. (1977). Self-organization in nonequilibrium systems: From dissipative structures to order through fluctuations. Wiley, New York.

- ↑ Prigogine, I. and Stengers, I. (1984). Order out of chaos: Man's new dialogue with nature. Bantam Books.

- ↑ Nicolis, G. and Prigogine, I. (1977). Self-organization in nonequilibrium systems: From dissipative structures to order through fluctuations. Wiley, New York.

- ↑ Prigogine, I. and Stengers, I. (1984). Order out of chaos: Man's new dialogue with nature. Bantam Books.

- ↑ Ahmed, Furqan; Tirkkonen, Olav (January 2016). "Simulated annealing variants for self-organized resource allocation in small cell networks". Applied Soft Computing. 38: 762–70. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2015.10.028.

- ↑ Palmer, Ada (October 2014). Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72557-7. http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674725577. "Ada Palmer explores how Renaissance readers, such as Machiavelli, Pomponio Leto, and Montaigne, actually ingested and disseminated Lucretius, ... and shows how ideas of emergent order and natural selection, so critical to our current thinking, became embedded in Europe’s intellectual landscape before the seventeenth century."

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 German Aesthetic. CUP Archive. pp. 64–. GGKEY:TFTHBB91ZH2. https://books.google.com/books?id=eC88AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA64.

- ↑ Carnot, S. (1824/1986). Reflections on the motive power of fire, Manchester University Press, Manchester UK,

- ↑ Clausius, R. (1850). "Ueber die bewegende Kraft der Wärme und die Gesetze, welche sich daraus für die Wärmelehre selbst ableiten Lassen". Annalen der Physik. 79 (4): 368–97, 500–24. Bibcode:1850AnP...155..500C. doi:10.1002/andp.18501550403. hdl:2027/uc1.$b242250. Translated into English: Clausius, R. (July 1851). "On the Moving Force of Heat, and the Laws regarding the Nature of Heat itself which are deducible therefrom". London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 4th. 2 (VIII): 1–21, 102–19. doi:10.1080/14786445108646819. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Ruse, Michael (2013). "17. From Organicism to Mechanism-and Halfway Back?". In Henning, Brian G.; Scarfe, Adam. Beyond Mechanism: Putting Life Back Into Biology. Lexington Books. p. 419. ISBN 9780739174371. https://books.google.com/books?id=3VtosxAtq-EC.

- ↑ Asaro, P. (2007). "Heinz von Foerster and the Bio-Computing Movements of the 1960s" in Albert Müller and Karl H. Müller (eds.) An Unfinished Revolution? Heinz von Foerster and the Biological Computer Laboratory BCL 1958–1976. Vienna, Austria: Edition Echoraum.

- ↑ As an indication of the increasing importance of this concept, when queried with the keyword self-organ*, Dissertation Abstracts finds nothing before 1954, and only four entries before 1970. There were 17 in the years 1971–1980; 126 in 1981–1990; and 593 in 1991–2000.

- ↑ Phys.org, Self-organizing robots: Robotic construction crew needs no foreman (w/ video), February 13, 2014.

- ↑ Science Daily, Robotic systems: How sensorimotor intelligence may develop... self-organized behaviors , October 27, 2015.

- ↑ Zeiger, H. J. and Kelley, P. L. (1991) "Lasers", pp. 614–19 in The Encyclopedia of Physics, Second Edition, edited by Lerner, R. and Trigg, G., VCH Publishers.

- ↑ Ansari M. H. (2004) Self-organized theory in quantum gravity. arxiv.org

- ↑ Lehn, J.-M. (1988). "Perspectives in Supramolecular Chemistry-From Molecular Recognition towards Molecular Information Processing and Self-Organization". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 27 (11): 89–121. doi:10.1002/anie.198800891.

- ↑ Bray, William C. (1921). "A periodic reaction in homogeneous solution and its relation to catalysis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 43 (6): 1262–67. doi:10.1021/ja01439a007.

- ↑ Rego, J.A.; Harvey, Jamie A.A.; MacKinnon, Andrew L.; Gatdula, Elysse (January 2010). "Asymmetric synthesis of a highly soluble 'trimeric' analogue of the chiral nematic liquid crystal twist agent Merck S1011" (PDF). Liquid Crystals. 37 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1080/02678290903359291. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-04-13.

- ↑ Love; Estroff, Lara A.; Kriebel, Jennah K.; Nuzzo, Ralph G.; Whitesides, George M. (2005). "Self-Assembled Monolayers of Thiolates on Metals as a Form of Nanotechnology". Chem. Rev. 105 (4): 1103–70. doi:10.1021/cr0300789. PMID 15826011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Barlow, S.M.; Raval R.. (2003). "Complex organic molecules at metal surfaces: bonding, organisation and chirality". Surface Science Report. 50 (6–8): 201–341. Bibcode:2003SurSR..50..201B. doi:10.1016/S0167-5729(03)00015-3.

- ↑ Ritu, Harneet (2016). "Large Area Fabrication of Semiconducting Phosphorene by Langmuir-Blodgett Assembly". Sci. Rep. 6: 34095. arXiv:1605.00875. Bibcode:2016NatSR...634095K. doi:10.1038/srep34095. PMC 5037434. PMID 27671093.

- ↑ Camazine, Deneubourg, Franks, Sneyd, Theraulaz, Bonabeau, Self-Organization in Biological Systems, Princeton University Press, 2003.

- ↑ Bonabeau, Eric; et al. (May 1997). "Self-organization in social insects" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 12 (5): 188–93. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01048-3. PMID 21238030.

- ↑ Couzin, Iain D.; Krause, Jens (2003). "Self-Organization and Collective Behavior in Vertebrates" (PDF). Advances in the Study of Behavior. 32: 1–75. doi:10.1016/S0065-3454(03)01001-5. ISBN 9780120045327. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20.

- ↑ Fox, Ronald F. (December 1993). "Review of Stuart Kauffman, The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution". Biophys. J. 65 (6): 2698–99. Bibcode:1993BpJ....65.2698F. doi:10.1016/s0006-3495(93)81321-3. PMC 1226010.

- ↑ Goodwin, Brian (2009). Beyond the Darwinian Paradigm: Understanding Biological Forms. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Johnson, Brian R.; Lam, Sheung Kwam (2010). "Self-organization, Natural Selection, and Evolution: Cellular Hardware and Genetic Software". BioScience. 60 (11): 879–85. doi:10.1525/bio.2010.60.11.4.

- ↑ Serugendo, Giovanna Di Marzo; et al. (June 2005). "Self-organization in multi-agent systems". Knowledge Engineering Review. 20 (2): 165–89. doi:10.1017/S0269888905000494.

- ↑ Yang, X. S.; Deb, S.; Loomes, M.; Karamanoglu, M. (2013). "A framework for self-tuning optimization algorithm". Neural Computing and Applications. 23 (7–8): 2051–57. arXiv:1312.5667. Bibcode:2013arXiv1312.5667Y. doi:10.1007/s00521-013-1498-4.

- ↑ X. S. Yang (2014) Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms, Elsevier.

- ↑ Watts, Duncan J.; Strogatz, Steven H. (June 1998). "Collective dynamics of 'small-world' networks". Nature. 393 (6684): 440–42. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..440W. doi:10.1038/30918. PMID 9623998.

- ↑ Clauset, Aaron; Cosma Rohilla Shalizi; M. E. J Newman (2009). "Power-law distributions in empirical data". SIAM Review. 51 (4): 661–703. arXiv:0706.1062. Bibcode:2009SIAMR..51..661C. doi:10.1137/070710111.

- ↑ Zhang, Q., Cheng, L., and Boutaba, R. (2010). "Cloud computing: state-of-the-art and research challenges". Journal of Internet Services and Applications. 1 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1007/s13174-010-0007-6.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Marinescu, D. C.; Paya, A.; Morrison, J. P.; Healy, P. (2013). "An auction-driven self-organising cloud delivery model". arXiv:1312.2998 [cs.DC].

- ↑ Lynn; et al. (2016). "Cloudlightning: A Framework for a Self-organising and Self-managing Heterogeneous Cloud". Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science: 333. doi:10.5220/0005921503330338. ISBN 978-989-758-182-3.

- ↑ Wiener, Norbert (1962) "The mathematics of self-organising systems". Recent developments in information and decision processes, Macmillan, N. Y. and Chapter X in Cybernetics, or control and communication in the animal and the machine, The MIT Press.

- ↑ Cybernetics, or control and communication in the animal and the machine, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and Wiley, NY, 1948. 2nd Edition 1962 "Chapter X "Brain Waves and Self-Organizing Systems" pp. 201–02.

- ↑ Ashby, William Ross (1952) Design for a Brain, Chapter 5 Chapman & Hall

- ↑ Conant, R. C.; Ashby, W. R. (1970). "Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system" (PDF). Int. J. Systems Sci. 1 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1080/00207727008920220.

- ↑ von Foerster, Heinz; Pask, Gordon (1961). "A Predictive Model for Self-Organizing Systems, Part I". Cybernetica. 3: 258–300.

- ↑ von Foerster, Heinz; Pask, Gordon (1961). "A Predictive Model for Self-Organizing Systems, Part II". Cybernetica. 4: 20–55.

- ↑ "Brain of the Firm" Alan Lane (1972); see also Viable System Model in "Beyond Dispute", and Stafford Beer (1994) "Redundancy of Potential Command" pp. 157–58.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Pask, Gordon (1996). "Heinz von Foerster's Self-Organisation, the Progenitor of Conversation and Interaction Theories" (PDF). Systems Research. 13 (3): 349–62. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-1735(199609)13:3<349::aid-sres103>3.3.co;2-7.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Pask, G. (1973). Conversation, Cognition and Learning. A Cybernetic Theory and Methodology. Elsevier

- ↑ Green, N. (2001). "On Gordon Pask". Kybernetes. 30 (5/6): 673–82. doi:10.1108/03684920110391913.

- ↑ Pask, Gordon (1993) Interactions of Actors (IA), Theory and Some Applications.

- ↑ Interactive models for self organization and biological systems Center for Models of Life, Niels Bohr Institute, Denmark

- ↑ Luhmann, Niklas (1995) Social Systems. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Biel, R.; Mu-Jeong Kho (November 2009). "The Issue of Energy within a Dialectical Approach to the Regulationist Problematique" (PDF). Recherches & Régulation Working Papers, RR Série ID 2009-1. Association Recherche & Régulation: 1–21. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ Marshall, A. (2002) The Unity of Nature, Chapter 5. Imperial College Press.

- ↑ Rogers.C. (1969). Freedom to Learn. Merrill

- ↑ Thomas L.F. & Augstein E.S. (1985) Self-Organised Learning: Foundations of a conversational science for psychology. Routledge (1st Ed.)

- ↑ Thomas L.F. & Augstein E.S. (1994) Self-Organised Learning: Foundations of a conversational science for psychology. Routledge (2nd Ed.)

- ↑ Thomas L.F. & Augstein E.S. (2013) Learning: Foundations of a conversational science for psychology. Routledge (Psy. Revivals)

- ↑ Harri-Augstein E. S. and Thomas L. F. (1991) Learning Conversations: The S-O-L way to personal and organizational growth. Routledge (1st Ed.)

- ↑ Harri-Augstein E. S. and Thomas L. F. (2013) Learning Conversations: The S-O-L way to personal and organizational growth. Routledge (2nd Ed.)

- ↑ Harri-Augstein E. S. and Thomas L. F. (2013)Learning Conversations: The S-O-L way to personal and organizational growth. BookBaby (eBook)

- ↑ Illich. I. (1971) A Celebration of Awareness. Penguin Books.

- ↑ Harri-Augstein E. S. (2000) The University of Learning in transformation

- ↑ Schumacher, E. F. (1997) This I Believe and Other Essays (Resurgence Book).

- ↑ Revans R. W. (1982) The Origins and Growth of Action Learning Chartwell-Bratt, Bromley

- ↑ Thomas L.F. and Harri-Augstein S. (1993) "On Becoming a Learning Organisation" in Report of a 7 year Action Research Project with the Royal Mail Business. CSHL Monograph

- ↑ Rogers C.R. (1971) On Becoming a Person. Constable, London

- ↑ Prigogyne I. & Sengers I. (1985) Order out of Chaos Flamingo Paperbacks. London

- ↑ Capra F (1989) Uncommon Wisdom Flamingo Paperbacks. London

- ↑ Bohm D. (1994) Thought as a System. Routledge.

- ↑ Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak-experiences, Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- ↑ Conversational Science Thomas L.F. and Harri-Augstein E.S. (1985)

- ↑ Kerner, Boris S. (1998). "Experimental Features of Self-Organization in Traffic Flow". Physical Review Letters. 81 (17): 3797–3800. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..81.3797K. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.81.3797.

- ↑ De Boer, Bart (2011). Gibson, Kathleen R.. ed. Self-organization and language evolution. Oxford.

- ↑ Bollen, Johan (8 August 2018). "Who would you share your funding with?". Nature (in English). 560 (7717): 143. Bibcode:2018Natur.560..143B. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-05887-3. PMID 30089925.

- ↑ Coelho, Andre. "NETHERLANDS: A radical new way do fund science | BIEN". Retrieved 2 June 2019.

编者推荐

- 超级碗和奥运会开幕式上的无人机表演,都只是人为控制的程序,而在最近一期的 Science 子刊 Science Robitics 上,研究者经过算法优化和参数调节,让无人机群自发形成了非常优美的、自组织的集群行为,详见《Science Robotics:无人机的自组织飞行和集群智慧》

- 交通拥堵有没有可能“自行治愈”?答案是肯定的,研究人员提出了一种新颖的自组织交通管理策略,一旦所有受影响的交通流量沿着剩余的道路容量重新分配,交通网络就会“自行治愈”,详见《自愈路网:城市道路网交通事故的自组织管理策略 | 论文速递10篇》

- 混合型社会是一种由不同组件组成的自组织的集群系统,这种自组织混合型社会面临哪些挑战?又有怎样的解决思路?请见《混合型社会:设计自组织系统集群行为的挑战及前景 | 复杂性文摘》

- 北京师范大学系统科学学院教授狄增如亲授《自组织理论》,帮助梳理了科学的发展脉络,介绍了时间反演对称、热力学第二定律及自组织现象的理论方法。

- 北京师范大学系统科学学院教授李红刚亲授《结构与功能:从无序到有序》,一起探讨系统的结构与功能,聚焦于自组织涌现,如何从无序走向有序。

本中文词条由木子二月鸟用户参与编译, 刘佩佩 用户审校,欢迎在讨论页面留言。

本词条内容源自wikipedia及公开资料,遵守 CC3.0协议。